Uzbekistan

| O‘zbekiston Respublikasi Ўзбекистон Республикаси O'zbekstan Respublikası Republic of Uzbekistan |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: National Anthem of the Republic of Uzbekistan "O‘zbekiston Respublikasining Davlat Madhiyasi" |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Tashkent 41°16′N 69°13′E | |||||

| Official languages | Uzbek | |||||

| Recognized regional languages | Uzbek • Russian • Karakalpak • Tajik • Koryo-mar • Turkmen • Ukrainian • Azerbaijani • Uyghur • Central Asian Arabic • Bukhori | |||||

| Language for inter-ethnic communication |

Russian | |||||

| Ethnic groups | 84.4% Uzbeks 4.9% Tajiks 2.4% Kazakhs 2.2% Karakalpaks 2.1% Russians 0.8% Kyrgyzs 0.6% Turkmens 0.5% Volga and Crimean Tatars 0.5% Koryo-sarams 0.2% Ukrainians and Belarusians 0.2% Armenians 0.1% Azerbaijanis 1.1% Others |

|||||

| Demonym | Uzbek | |||||

| Government | Presidential Republic | |||||

| - | President | Shavkat Mirziyoyev | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Abdulla Aripov | ||||

| Independence | from the Soviet Union | |||||

| - | Formation | 17471 | ||||

| - | Uzbek SSR | October 27, 1924 | ||||

| - | Declared | September 1, 1991 | ||||

| - | Recognized | December 8, 1991 | ||||

| - | Completed | December 25, 1991 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 447,400 km² (56th) 172,742 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 4.9 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2020 estimate | 34,558,900[1] (41st) | ||||

| - | Density | 74.1/km² (128nd) 182.8/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $335.806 billion[2] (53) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $9,007[2] (154th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $72.762 billion[2] (75th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $1,900[2] (170th) | ||||

| Gini (2013) | 36.7[3] (88th) | |||||

| Currency | Uzbekistan som (O'zbekiston so'mi) (UZS) |

|||||

| Time zone | UZT (UTC+5) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | not observed (UTC+5) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .uz | |||||

| Calling code | [[+998]] | |||||

| 1 | As Emirate of Bukhara, Kokand Khanate, Khwarezm. | |||||

Uzbekistan, officially the Republic of Uzbekistan, is a doubly-landlocked country in Central Asia, formerly of the Soviet Union, surrounded entirely by other landlocked states.

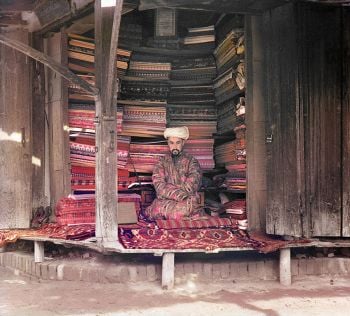

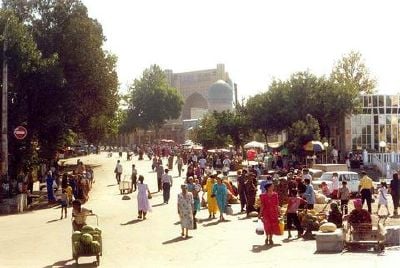

Located in the heart of Central Asia between the Amu Darya (Oxus) and Syr Darya (Jaxartes) Rivers, Uzbekistan has a long and interesting heritage. The leading cities of the Silk Road (the ancient trade route that linked China with the West) - Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva - are located in Uzbekistan.

Once a thriving culture, Uzbekistan suffered from revolution and unrest within the Soviet Union of the twentieth century. In addition, the heavy use of agrochemicals, diversion of huge amounts of irrigation water from the two rivers that feed the region, and the chronic lack of water treatment plants have caused health and environmental problems on an enormous scale.

Much work is left to be done in order to uplift the Uzbeki people and allow them to flourish. Active measures must be taken to overcome rampant corruption, revive both the economic and educational systems and support environmental clean up and rebirth. In this, Uzbekistan's good relationship with other nations is vital.

Geography

There are different opinions on the source of the name "Uzbek." One view is that the name comes from a leader of the Golden Horde in the fourteenth century, who was named Uzbek. Another view is that the name comes from the period the Russians first encountered the people. Ozum bek, means "I am the lord (or ruler)." The word “oz” means “leader” and “bek” means “noble.”

Bordering Turkmenistan to the southwest, Kazakhstan and the Aral Sea to the north, and Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to the south and east, Uzbekistan is not only one of the larger Central Asian states but also the only Central Asian state to border all of the other four. Uzbekistan also shares a short border with Afghanistan to the south.

With a land area of 172,700 square miles, (447,400 square kilometres, Uzbekistan is approximately the size of Morocco or the U.S. state of California and is the 56th-largest country (after Sweden). Uzbekistan stretches 885 miles (1425 km) from west to east and 578 miles (930km) from north to south.

Uzbekistan is a dry country of which 10 percent consists of intensely cultivated, irrigated river valleys. It is one of two double-landlocked countries in the world (the other being Liechtenstein).

The physical environment ranges from the flat, desert topography that comprises almost 80 percent of the country territory to mountain peaks in the east. The highest point is Adelunga Togh at 14,111 feet (4301 meters) above sea level

Southeastern Uzbekistan is characterized by the foothills of the Tian Shan mountains, which form a natural border between Central Asia and China. The vast Qizilqum ("red sand") Desert, shared with southern Kazakhstan, dominates the northern lowland region. The most fertile part of Uzbekistan, the Fergana Valley, is an area of about 21,440 square kilometers directly east of the Qizilqum and surrounded by mountain ranges to the north, south, and east. The western end of the valley is defined by the course of the Syr Darya, which runs across the northeastern sector of Uzbekistan from southern Kazakhstan into the Qizilqum.

Water resources are unevenly distributed, and in short supply. The vast plains that occupy two-thirds of Uzbekistan's territory have little water, and there are few lakes. The two largest rivers are the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, which originate in the mountains of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, respectively.

The mountain areas are especially prone to earthquakes. Indeed, much of Uzbekistan's capital city, Tashkent, was destroyed in an earthquake in 1966.

Tashkent is the capital of Uzbekistan and also of Tashkent Province. The population of the city in 2006 was 1,967,879. The leading cities of the Silk Road - Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva - are located in Uzbekistan.

Climate

Uzbekistan has a continental climate, with hot summers and cool winters. Summer temperatures often surpass 104°F (40°C), while winter temperatures average about –9.4°F (-23°C), but may fall as low as -40°C. Most of the country is quite arid, with average annual rainfall amounting to between four and eight inches (100mm and 200mm) and occurring mostly in winter and spring. Between July and September, little precipitation falls, essentially stopping the growth of vegetation during that period.

Flora and fauna

Vegetation patterns in Uzbekistan vary largely according to altitude. The lowlands in the west have a thin natural cover of desert sedge and grass. The high foothills in the east support grass, and forests and brushwood appear on the hills. Forests cover less than 12 percent of Uzbekistan's area.

Animal life in the deserts and plains includes extremely rare Saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica) and a large lizard (desert monitor) that can reach lengths of five feet (1.6 meters), the Bukhara Deer, wild boar, pheasant, and golden eagle, as well as rodents, foxes, wolves, and occasional gazelles. Boars, roe deer, bears, wolves, Siberian goats, and some lynx live in the high mountains.

But the heavy use of agrochemicals, diversion of huge amounts of irrigation water from the two rivers that feed the region, and the chronic lack of water treatment plants have caused health and environmental problems on an enormous scale.

Environmental problems

Despite Uzbekistan's rich and varied natural environment, decades of environmental neglect in the Soviet Union have combined with skewed economic policies in the Soviet south to make Uzbekistan one of the gravest of the CIS's many environmental crises. The heavy use of agrochemicals, diversion of huge amounts of irrigation water from the two rivers that feed the region, and the chronic lack of water treatment plants are among the factors that have caused health and environmental problems on an enormous scale.

The most visible damage has been to the Aral Sea, which in the 1970s was larger than most of the Great Lakes of North America. Sharply increased irrigation caused the sea to shrink, so that by 1993, the Aral Sea had lost an estimated 60 percent of its volume, and was breaking into three unconnected segments. Increasing salinity and reduced habitat killed the fish, destroying its fishing industry. The depletion of this large body of water has increased temperature variations in the region, which has harmed agriculture.

Every year, many tons of salt and dust from the sea's dried bottom are carried as far as 500 miles (800km) away, and has led to the large-scale loss of plant and animal life, loss of arable land, changed climatic conditions, depleted yields on the cultivated land that remains, and destruction of historical and cultural monuments.

In the early 1990s, about 60 percent of pollution control funding went to water-related projects, but only about half of cities and about one-quarter of villages have sewers. Communal water systems do not meet health standards. Much of the population lacks drinking water systems and must drink water straight from contaminated irrigation ditches, canals, or the Amu Darya itself. According to one report, virtually all the large underground fresh-water supplies in Uzbekistan are polluted by industrial and chemical wastes.

Fewer than half of factory smokestacks in Uzbekistan have filters, and none has the capacity to filter gaseous emissions. In addition, a high percentage of existing filters are defective or out of operation.

The government has acknowledged the extent of the problem, and it has made a commitment to address them in its Biodiversity Action Plan. But the government's environmental structures remain confused and ill defined.

History

The territory of Uzbekistan was populated in the second millennium B.C.E. Early human tools and monuments have been found in the Ferghana, Tashkent, Bukhara, Khorezm, and Samarkand regions.

The first civilizations to appear in Uzbekistan were Sogdiana, Bactria and Khwarezm. Territories of these states became a part of Persian Achaemenid Dynasty in the sixth century B.C.E.

Alexander the Great conquered Sogdiana and Bactria in 327 B.C.E., marrying Roxane, daughter of a local Sogdian chieftain. However, the conquest was of little help to Alexander as popular resistance was fierce, causing Alexander's army to be bogged down in the region. The territory of Uzbekistan was referred to as Transoxiana until the eighth century.

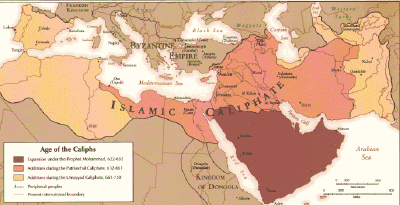

The Middle Ages

Muslim Arabs conquered the area in the eighth century C.E. A century later, the Persian Samanid dynasty established an empire, and encouraged Persian culture in the area. Later, the Samanid empire was overthrown by the Kara-Khanid Khanate. Uzbekistan and rest of Central Asia was invaded by Genghis Khan and his Mongol tribes in 1220.

In the 1300s, Timur (1336-1405), known in the west as Tamerlane, overpowered the Mongols and built his own empire. In his military campaigns, Tamerlane reached as far as the Middle East. He defeated Ottoman Emperor Bayezid I and rescued Europe from Turkish conquest.

Tamerlane sought to build a capital of his empire in Samarkand. From each campaign he would send artisans to the city, sparing their lives. Samarkand became home for many people; there used to be Greek and Chinese, Egyptian and Persian, Syrian and Armenian neighborhoods. Uzbekistan's most noted tourist sights date from the Timurid dynasty. Later, separate Muslim city-states emerged with strong ties to Persia.

Russian influence

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were some 2000 miles (3200km) separating British India and the outlying regions of the Imperial Russia. Much of the land in between was unmapped. At that time, the Russian Empire began to expand, and spread into Central Asia. The "Great Game" period, of rivalry and strategic conflict between the British Empire and the Tsarist Russian Empire for supremacy in Central Asia, is generally regarded as running from approximately 1813 to the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907.

In 1865, Russia occupied Tashkent, and by the end of the nineteenth century, Russia had conquered all of Central Asia. In 1876, the Russians dissolved the Khanate of Kokand, while allowing the Khanate of Khiva and the Emirate of Bukhara to remain as direct protectorates. Russia placed the rest of Central Asia under colonial administration, and invested in the development of Central Asia's infrastructure, promoting cotton growing, and encouraging settlement by Russian colonists. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Central Asia was firmly in the hands of Russia.

Soviet rule

Despite some early resistance to Bolsheviks, Uzbekistan and the rest of Central Asia became a part of the Soviet Union. In 1924, the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic was created, including most of the territories of the Emirate of Bukhara and Khanate of Khiva as well as portions of the Fergana Valley that had constituted the Khanate of Kokand.

Moscow used Uzbekistan for its tremendous cotton-growing ("white gold"), grain, and natural resource potential. The extensive and inefficient irrigation used to support cotton has been the main cause of shrinkage of the Aral Sea.

President Islom Kharimov became the Communist Party's First Secretary in Uzbekistan in 1989. Minorities in Ferghana Valley were attacked. Kharimov was returned as president of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in March 1990, in elections in which few opposition groups are allowed to field candidates.

Independence

On April 7, 1990, the Soviet Union passed a law allowing republics to leave the union if two thirds of their voters wished to. On August 31, 1991, Uzbekistan reluctantly declared independence, marking September 1 as a national holiday. In subsequent ethnic tensions, two million Russians left the country for Russia.

In 1992, Kharimov banned the Birlik and Erk (Freedom) parties. Large numbers of opposition party members were arrested for alleged anti-state activities.

In 1999, bomb blasts in the capital, Tashkent, kill more than a dozen people. Kharimov blames the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), which broadcasts a declaration of jihad from a radio station in Iran demanding the resignation of the Uzbek leadership. Insurgents launched a series of attacks against government forces from mountain hideouts.

In 2000, Kharimov was re-elected president in elections Western observers called neither free nor fair. New York-based Human Rights Watch accused Uzbekistan of widespread use of torture.

In January 2002, Kharimov won support for extending his presidential term from five to seven years in a referendum criticized by the West as a ploy to retain power.

On May 13, 2005, Uzbek troops fired on thousands of protesters in the eastern town of Andijon. Uzbek authorities maintain that only 176 people died during the clashes, most of them "terrorists" and their own soldiers. Conservative estimates put the death toll around 500.

The country now seeks to gradually lessen its dependence on agriculture - it is the world's second-largest exporter of cotton - while developing its mineral and petroleum reserves. While departing from communism, Karimov has retained authoritarian control over the independent state.

Government and politics

The politics of Uzbekistan take place in the framework of a presidential republic, whereby the president is chief of state. The nature of government is authoritarian presidential rule, with little power outside the executive branch. The president is elected by popular vote for a seven-year term, and is eligible for a second term.

The president appoints the prime minister, a cabinet of ministers, and their deputies. The Supreme Assembly approves the cabinet.

The bicameral Supreme Assembly or Oliy Majlis consists of a senate of 100 seats. Regional governing councils elect 84 members to serve five-year terms, and the president appoints 16. The legislative chamber comprises 120 seats. Members are elected by popular vote to serve five-year terms.

Judicial system

Although the constitution requires independent judges, the judicial system lacks independence. Supreme Court judges are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Supreme Assembly. The legal system is an evolution of Soviet civil law. Defendants are seldom acquitted, and if they are, the government can appeal. Reports of police abuse and torture are widespread. People are reluctant to call the police, as they are not trusted. Petty crime has become more common, while violent crime is more rare. Although police are tough on drug abuse, heroin use has increased since it is available. Heroin is shipped through Uzbekistan from Afghanistan and Pakistan to Europe.

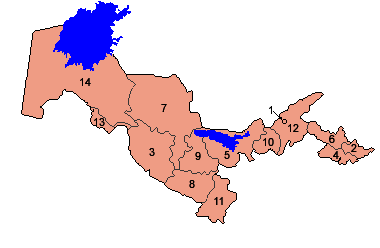

Administrative divisions

Uzbekistan is divided into 12 provinces or viloyat, one autonomous republic, and one independent city. They are: Tashkent City, 1; Andijan Province, 2; Buxoro Province, 3; Fergana Province, 4; Jizzax Province, 5; Xorazm Province, 13; Namangan Province, 6; Navoiy Province, 7; Qashqadaryo Province, 8; Karakalpakstan Republic, 14; Samarqand Province, 9; Sirdaryo Province, 10; Surxondaryo Province, 11; Toshkent Province, 12.

Enclaves and exclaves

An “enclave” is a country or part of a country mostly surrounded by the territory of another country or wholly lying within the boundaries of another country, and an “exclave” is one that is geographically separated from the main part by surrounding alien territory. There are four Uzbek exclaves, all of them surrounded by Kyrgyz territory in the Fergana Valley region where Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan meet.

Exclaves include: Sokh, with an area of 125 square miles (325km²) is populated primarily by Tajiks with a small number of Uzbeks; Shakhrimardan (also known as Shakirmardon or Shah-i-Mardan), with an area of 35 square miles (90km²), comprises 91 percent Uzbeks and the remainder Kyrgyz; Chong-Kara (or Kalacha), on the Sokh river, between the Uzbek border and Sokh, is roughly two miles (3km) long by 0.6 miles (1km) wide; and Dzhangail, a dot of land barely 1.5 miles (2 or 3km) across.

Uzbekistan has a Tajikistan enclave, the village of Sarvan, which includes a narrow, long strip of land about nine miles (15km) long by 0.6 miles (1km) wide, alongside the road from Angren to Kokand. There is also a tiny Kyrgyzstan enclave, the village of Barak, between the towns of Margilan and Fergana.

Military

Uzbekistan possesses the largest military force in Central Asia, having around 65,000 people in uniform. Its structure is inherited from the Soviet armed forces, although it is being restructured around light and Special Forces. Equipment is not modern, and training, while improving, is neither uniform nor adequate. The government has accepted the arms control obligations of the former Soviet Union, acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and supported the U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency in western Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan approved the U.S. request for access to a vital military air base, Karshi-Khanabad, in southern Uzbekistan following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the U.S. After the Andijan riot and subsequent U.S. reaction, Uzbekistan demanded that the U.S. withdraw. The last US troops left Uzbekistan in November 2005.

Foreign relations

Uzbekistan joined the Commonwealth of Independent States in December 1991, but withdrew from the CIS collective security arrangement in 1999. Since that time, Uzbekistan has participated in the CIS peacekeeping force in Tajikistan and in UN-organized groups to help resolve the Tajik and Afghan conflicts, both of which it sees as posing threats to its own stability.

Uzbekistan supported U.S. efforts against worldwide terrorism and joined the coalitions that have dealt with both Afghanistan and Iraq. The relationship with the United States began to deteriorate after the so-called "color revolutions" in Georgia and Ukraine, when the U.S. joined in a call for an investigation of the events at Andijon, when up to 500 people were killed when police fired on protesters.

It is a member of the United Nations, the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council, Partnership for Peace, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). It belongs to the Organization of the Islamic Conference and the Economic Cooperation Organization—comprising the five Central Asian countries, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Uzbekistan is a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and hosts the SCO’s Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) in Tashkent. Uzbekistan joined the new Central Asian Cooperation Organization (CACO) in 2002. The CACO consists of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. It is a founding member of the Central Asian Union, formed with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, joined in March, 1998, by Tajikistan.

Economy

Uzbekistan is the world's second-largest cotton exporter and fifth largest producer. It relies heavily on cotton production as the main source of export earnings. Other export earners include gold, natural gas, and oil.

After independence, the government sought to prop up its Soviet-style command economy with subsidies and tight controls on production and prices. While aware of the need to improve the investment climate, the government still sponsors measures that often increase, not decrease, its control over business decisions.

After independence, Uzbekistan moved to private property ownership. From 1992, Uzbeks were able to buy their homes from the state for the equivalent of three months' salary. Ownership of agricultural land, which had been state-owned during the Soviet period, has been assumed by the families or communities that farmed the land. The new owners are still subject to state controls. About 60 percent of small businesses and services are privately owned. Large factories remain state-owned.

The economic policies have repelled foreign investment, which is the lowest per capita in the Commonwealth of Independent States.

A sharp increase in the inequality of income distribution has hurt the lower ranks of society since independence. In 2003, the government accepted the obligations of Article VIII under the International Monetary Fund (IMF), providing for full currency convertibility. However, strict currency controls and tightening of borders have lessened the effects of convertibility and have also led to some shortages that have further stifled economic activity. The Central Bank often delays or restricts convertibility, especially for consumer goods.

Tashkent, the nation's capital and largest city, has a three-line subway built in 1977, and expanded 2001. Uzbekistan is considered as the only country in Central Asia with subway system that is considered as one of the cleanest subway systems in the world.

Potential investment by Russia and China in Uzbekistan's gas and oil industry may boost growth prospects. In November 2005, Russian President Vladimir Putin and President Kharimov signed an "alliance," which included provisions for economic and business cooperation. Russian businesses have shown increased interest in Uzbekistan, especially in mining, telecommunications, and oil and gas. In December 2005, the Russians opened a "Trade House" to support and develop Russian-Uzbek business and economic ties.

In 2006 Uzbekistan took steps to rejoin the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) and the Eurasian Economic Community (EurASEC), both organizations dominated by Russia. Uzbek authorities have accused US and other foreign companies operating in Uzbekistan of violating Uzbek tax laws and have frozen their assets. US firms have not made major investments in Uzbekistan in the last five years.

Export commodities include cotton, gold, energy products, mineral fertilizers, ferrous and non-ferrous metals, textiles, food products, machinery, and automobiles. Export partners include Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Ukraine, Bangladesh, Poland, and Tajikistan.

Import commodities include machinery and equipment, foodstuffs, chemicals, ferrous and non-ferrous metals. Import partners include Russia, South Korea, Germany, Kazakhstan, China, Turkey, and Ukraine.

Demographics

Population

Uzbekistan is Central Asia's most populous country. Its people, concentrated in the south and east of the country, comprise nearly half the region's total population. Uzbekistan had been one of the poorest republics of the Soviet Union; much of its population was engaged in cotton farming in small rural collective farms (kolkhoz|). In the recent years, the fraction of the rural population has continued to increase.

Ethnicity

Uzbekistan has a wide mix of ethnic groups and cultures, with the Uzbeks being the majority group of over 80 percent. The chief minority groups include Russians, Tajiks, an ethnic group closely related to the Persians, Kazaks, Tatars, and Karakalpaks. The number of non-indigenous people there is decreasing as Russians and other minority groups slowly leave and Uzbeks return from other parts of the former Soviet Union.

When the Uzbekistan region was formed as part of the Soviet Union in 1924 the Soviet government paid little attention to which areas had been settled by Uzbeks and which had not. As a result the country includes two main Tajik cultural centers at Bukhoro and Samarqand, as well as parts of the Fergana Valley to which other ethnic groups could lay claim.

Religion

Uzbeks come from a predominantly Sunni Muslim background, usually of the Hanafi school, but variations exist between northern and southern Uzbeks. People living in the area of modern Uzbekistan were first converted to Islam as early as the eighth century C.E., as Arab troops invaded the area, displacing the earlier faiths of Zoroastrianism and Buddhism. The Arab victory over the Chinese in 751, at the Battle of Talas, ensured the future dominance of Islam in Central Asia.

Under Soviet rule, religion was tightly controlled. Uzbeks from the former USSR came to practice religion with a more liberal interpretation due to the official Soviet policy of atheism, while Uzbeks in Afghanistan and other countries to the south have remained more conservative.

When Uzbekistan gained independence, it was widely believed that Muslim fundamentalism would spread across the region. The Kharimov government cracked down on extremists, especially Wahhabism, that sprouted in the Ferghana Valley in the 1990s. A 1994 survey revealed few of those who said they were Muslim had any real knowledge of the religion or knew how to practice it. However Islam is increasing in the region. The nation is approximately 90 percent Muslim (mostly Sunni, with a small Shi'a minority).

Language

Uzbek, a Turkic language, is the only official state language. The language has numerous dialects, including Qarlug (the literary language for much of Uzbek history), Kipchak, Lokhay, Oghuz, Qurama, and Sart. Uzbek, identified as a distinct language in the fifteenth century, is close to modern Uyghur. Speakers of each language can converse easily. Russian is the de facto language for inter-ethnic communication, including much day-to-day technical, scientific, governmental and business use.

Men and women

Uzbekistan society is male-dominated. Women run the home and control the family budgets. In public, women must cover their bodies, but full veiling is not common. From the 1920s, women began to work at textile factories, in cotton fields, and in professional jobs opened to them by the Soviet education system. By 2007, women made up half the workforce, were represented in parliament, and held 18 percent of administrative and management positions, although men continued to hold most managerial positions, and the most labor-intensive jobs.

Marriage and the family

Marriages are often arranged, especially in traditional areas. Kin group partners are preferred. People marry young by Western standards, in their late teens or early 20s. Weddings last for days, and are paid for by the bride's family. A bride price may be paid by the husband's family. Polygamy is illegal and rare. Divorce has become more common.

The average family comprises five or six members. If possible, sons may build houses adjacent to their parents’ house. The youngest son and his bride will take care of his parents, and will inherit the family home. Sons inherit twice as much as daughters.

Babies are viewed only by immediate family members for their first 40 days, are tightly wrapped, and are cared for by their mothers. Children are held dear. When young, they have great freedom, but discipline increases as they get older. All do a share of the family's work.

Education

Traditional education had its origins in the medieval seminaries of Bukhara and Samarqand. This was later dominated by Russian and Soviet education. After independence, greater emphasis was placed on Uzbek literature and history, and the Russian language was discouraged.

All children must go to school for nine years, starting at age six, and schooling is free. Uzbekistan enjoys 99.3 percent literacy rate among people aged 15 and over.

However, due to budget constraints and other transitional problems following the collapse of the Soviet Union, texts and other school supplies, teaching methods, curricula, and educational institutions are outdated, inappropriate, and poorly kept. Additionally, the proportion of school-aged persons enrolled has been dropping. Although the government is concerned about this, budgets remain tight.

There are over 20 university-level institutions in the country. Enrollment in higher-education institutions is down from more than 30 percent during the Soviet period. Uzbek universities churn out almost 600,000 skilled graduates annually.

Class

Under Soviet rule, those well-placed in the government could get high-quality consumer goods, cars, and homes that others could not get. Since independence, many of these people have found positions that earn many times the average annual salary. However, numerous teachers, artists, doctors, and other skilled service providers have moved into unskilled jobs, as bazaar vendors and construction workers, to earn more money. The new rich buy expensive cars, apartments, and clothes, and to go to nightclubs. Foreign foods and goods are signs of wealth.

Culture

In Uzbek culture, elders are respected. Men greet each other with a handshake, while holding the left hand over the heart. Women must be modest, and may keep their head tilted down to avoid attention while in public. In traditional homes, women will not enter a room containing male guests..

Architecture

The cities of Samarkand and Bokhara were jewels of Islamic architecture, and remain tourist attractions. Buildings from the Soviet era were big and utilitarian, and often the same shape, size, and color throughout the Soviet empire. Large Soviet-designed apartment blocks were five or six stories high and had three to four apartments of one, two, or three bedrooms each per floor. In villages and suburbs, residents live in one-story houses built around a courtyard, all with a drab exterior, with the family's wealth and taste displayed only for guests. More separate houses have been built since independence.

The dusterhon, or tablecloth, either spread on the floor or on a table, is the center of the main room of the house. Each town has a large square, for festivals and public events. Parks are for promenading, and park benches are built in clusters, for neighbors to gather and chat.

Cuisine

Uzbek bread, tandir non, is flat and round, is always torn by hand, never placed upside down, and never thrown out. Meals begin with nuts and raisins, proceed to soups, salads, and meat dishes, and end with palov, a rice-and-meat dish. Other dishes include monti, steamed dumplings of lamb meat and fat, onions, and pumpkin, and kabob, grilled ground meat. Uzbeks prefer mutton and avoid pork. Many types of fruit and vegetables are available. Dairy products include katyk, a liquid yogurt, and suzma, similar to cottage cheese. Green tea is drunk throughout the day. Meals are served on a dusterhon, either on the floor, or on a low table.

The choyhona, or teahouse, is a gathering place for the neighborhood's men. Russians brought their foods, such as pelmeni, boiled meat dumplings, borscht, as well as cabbage and meat soup. Parties usually involve a large meal ending with palov, accompanied by vodka, cognac, wine, and beer. Toasts precede each round of shots.

Music

Uzbek music has reedy, haunting instruments and throaty, nasal singing. It is played on long-necked lutes called dotars, flutes, tambourines, and small drums. Uzbek classical music is called shashmaqam, which arose in Bukhara in the late sixteenth century when that city was a regional capital. Shashmaqam is closely related to Azeri mugam and Uyghur muqam. The name, which translates as six maqams refers to the structure of the music, which contains six sections in different musical modes, similar to classical Persian music. Interludes of spoken Sufi poetry interrupt the music, typically beginning at a low register and gradually ascending to a climax before calming back down to the beginning tone. Traditional instruments include: Dombra (lute), doyra (drum with jingles), rubob (lute), oud (pear-shaped string instrument), ney (an end-blown flute), surnay (horn), and tambur (a fretted, stringed instrument). Uzbek pop music combines folk music with electric instruments to create dance music.

Performing arts

Uzbek dance, which is characterized by fluid arm and upper-body movement, has different traditions: Bokhara and Samarkand; Khiva; and Khokand. Still danced is the Sufi zikr, accompanied by chanting and percussion to reach a trance. The Ilkhom Theater, founded in 1976, was the first independent theater in the Soviet Union.

Literature

Before the twentieth century, bakshi, elder minstrels passed on myths and history through epic songs, and otin-oy, women singers sang of birth, marriage and death.

Uzbekistan was the location of numerous writers, although not all were ethnic Uzbeks. The fifteenth-century poet Alisher Navoi, 1441–1501, wrote a treatise comparing the Persian and Turkish languages. Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, 973–1048, wrote a study on India. Ibn Sina, also known as Avicenna, 980–1037, wrote The Canon of Medicine. Omar Khayyam, 1048–1131, pursued mathematics and astronomy in Samarkand. The first Moghul (Muslim) leader of India, Babur, 1483–1530, was born in Uzbekistan, and is also famous for his autobiography.

Sport

Uzbekistan is home to former racing cyclist Djamolidine Abdoujaparov, who won the points contest in the Tour de France three times. Abdoujaparov was a specialist at winning stages in tours or one day races.

Uzbekistan is also the home of the traditional Uzbek fighting art of kurash. It is a Turkic wrestling art, related to the Turkish yagli gures and the Tatar köräş. It is an event in the Asian Games. There is an effort to include kurash in the Olympic games.

Notes

- ↑ Demografiya va mehnat statistikasi (Yanvar - Dekabr, 2020) Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 World Economic Outlook Database: Uzbekistan International Monetary Fund, October 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

- ↑ GINI index – Uzbekistan MECOMeter – Macro Economy Meter. Retrieved January 18, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allworth, Edward. The Modern Uzbeks: From the fourteenth century to the present: a cultural history. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University Press, 1990. ISBN 0817987312

- Bissell, Tom. Chasing the Sea: Being a narrative of a journey through Uzbekistan, including descriptions of life therein, culminating with an arrival at the Aral Sea, the world's worst man-made ecological catastrophe, in one volume. New York: Pantheon Books, 2003. ISBN 0375421300

- Critchlow, James. Nationalism in Uzbekistan: A Soviet Republic's road to sovereignty. Boulder: Westview Press, 1991. ISBN 0813384036

- Kalter, Johannes, and Margareta Pavaloi. Uzbekistan: Heirs to the silk road. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997. ISBN 0500974519

- Karimov, I. A. Uzbekistan on the Threshold of the Twenty-first Century: challenges to stability and progress. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998. ISBN 0312213689

- Khan, Aisha. A Historical Atlas of Uzbekistan. Historical atlases of South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East. New York: Rosen Pub. Group, 2003. ISBN 0823938689

- Murray, Craig. Murder in Samarkand: A British Ambassador's defiance of Tyranny. Edinburgh: Mainstream, 2006. ISBN 1845961943

- Rall, Ted. Silk road to ruin: is Central Asia the new Middle East? New York: NBM, 2006. ISBN 1561634549

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Uzbekistan. Countries and Their Cultures

- Uzbekistan CIA World Factbook

- U.S. Relations With Uzbekistan U.S. Department of State

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Uzbekistan history

- History_of_Uzbekistan history

- Geography_of_Uzbekistan history

- Economy_of_Uzbekistan history

- Demographics_of_Uzbekistan history

- Culture_of_Uzbekistan history

- Music_of_Uzbekistan history

- Kurash history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.