Afghanistan

| د افغانستان اسلامي جمهوریت (Da Afġānistān Islāmī Jomhoriyat) جمهوری اسلامی افغانستان (Jamhūrī-yi Islāmī-ye Afġānistān) Islamic Republic of Afghanistan | |||||

| |||||

| Anthem: Surūd-i Millī | |||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Kabul 34°31′N 69°08′E | ||||

| Official languages | Pashto Persian (Darī)[1] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government | Unitary Islamic caretaker government under an autocracy | ||||

| - Head | Hibatullah Akhundzada | ||||

| - Prime Minister | Hasan Akhund (acting) | ||||

| - Chief Justice | Abdul Hakim Ishaqzai) | ||||

| Independence | from the United Kingdom | ||||

| - Declared | August 8, 1919 | ||||

| - Recognized | August 19, 1919 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| - Total | 652,230 km² (42nd) 251,772 sq mi | ||||

| - Water (%) | negligible | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - 2021 estimate | 37,466,414[1] | ||||

| - Density | 54.9/km² 142/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $78.04 billion | ||||

| - Per capita | $2,000 | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $20.24 billion[1] | ||||

| - Per capita | $601 | ||||

| HDI (2020) | 0.511[2] (n/a) | ||||

| Currency | Afghani (Af) (AFN)

| ||||

| Internet TLD | .af | ||||

| Calling code | +93 | ||||

Afghānistān, officially the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (Pashto language: د افغانستان اسلامي جمهوریت, or Persian language: جمهوری اسلامی افغانستان), is a landlocked country located in the heart of Asia.

Afghanistan is a multi-ethnic state at a nexus where numerous Eurasian civilizations have interacted, traded, migrated through, and often fought. Invaders and conquerors included the Persian Empire, Alexander the Great, Muslim Arabs, Turkic peoples, the Mongols, the British Empire, and the Soviet Union. The Afghans historically have fiercely fought against outside forces that threatened their independence.

Geography

Afghanistan is located upon the geologic Iranian plateau. It is bordered by Pakistan in the south and east, Iran in the west, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in the north, and the People's Republic of China in the far northeast. Part of the region bordering Pakistan falls in the disputed Kashmir region, which is claimed by India.

The name Afghānistān translates to the “Land of Afghans.” The Pashtun people began using the term Afghan from at least the Islamic period. Until the nineteenth century, the name was only used for the traditional lands of the Pashtuns, while the kingdom as a whole was known as the Kingdom of Kabul. It has religious, ethno-linguistic, and geographic links with most of its neighbors.

At 249,984 square miles (647,500 square kilometers), Afghanistan is the world's 41st-largest country (after Myanmar). It is comparable in size to Somalia, and is slightly smaller than the U.S. state of Texas.

The terrain comprises mostly rugged mountains—the Hindu Kush and connected ranges—plains in north and southwest, and large areas of sandy desert near the southern border with Pakistan. The highest point is Nowshak, at 24,557 feet (7485 meters) above sea level. The lowest point is Amu Darya at 846 feet (258 meters). Large parts of the country are dry, and fresh water supplies are limited.

Important passes include the Unai Pass across the Sanglakh Range, and the Kotal-e Salang, connecting Kabul with central and northern Afghanistan. The famous Khyber Pass is in eastern Afghanistan. There are two passes from Paktika Province into Pakistan's Waziristan region, plus the Charkai River passage south of Khowst, Afghanistan. The busy Pakistan border crossing at Wesh connects Kandahar and Spin Boldak, Afghanistan, to Quetta, Pakistan.

Afghanistan has a dry, continental climate, with hot summers and cold winters. The sun shines for three-quarters of the year—the nights are clearer than the days. The highlands have a mean temperature of between 50°F to 60°F (10°C and 15°C). Daily temperatures can have up to a 30°F (17°C) difference between the coldest and hottest time. Waves of intense cold, lasting for several days, can reach 12°F below zero (minus 24°C). In Kabul, the snow lies for two or three months—the people seldom leave their houses, and sleep close to stoves. The summer heat is great everywhere, made worse in Kandahar by frequent dust storms and fiery winds. The bare rocky ridges that traverse the country absorb heat by day and radiate it by night. In the Oxus regions, a shade maximum of 110°F to 120°F (45°C to 50°C) is not uncommon. The summer rains that accompany the southwest monsoon in India travel up the Kabul valley as far as Laghman.

Most vegetation is confined to the main ranges and their immediate off-shoots. More distant ranges are naked rock and stone. Large conifers grow on the Safed Koh alpine range from 6,000 to 10,000 feet (1,800 to 3,000 meters). Down to 3,000 feet (1,000 meters) grow wild olive, rock-rose, wild privet, acacias and mimosas. Scanty vegetation on the western lowest ridges is almost wholly herbal. Mulberry, willow, poplar, and ash trees grow in cultivated districts.

Damaging earthquakes occur in the Hindu Kush mountains. Flooding and droughts occur in the south and southwest of the country.

The country's natural resources include gold, silver, copper, zinc, and iron ore in southeastern areas; precious and semi-precious stones such as lapis, emerald, and azure in the northeast; and potentially significant petroleum and natural gas reserves in the north. The country also has coal, chromite, talc, barites, sulfur, lead, and salt. War has caused of these mineral and energy resources to remain largely untapped.

There are four major rivers in the country: the Amu Darya, Hari Rud, Kabul, and Helmand rivers. There are also several smaller rivers and lakes.

Kābul is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan, with population of about three million people. It is an economic and cultural center, situated 5,900 feet (1800 meters) above-sea-level in a narrow valley, and wedged between the Hindu Kush mountains along the Kabul River. The other major cities are, in order of population size, Kandahar, Herat, Mazari Sharif, Jalalabad, Ghazni, and Kunduz.

History

Excavation of prehistoric sites suggests that humans were living in what is now Afghanistan at least 50,000 years ago. Historian Arnold Toynbee described the region as a "roundabout of the ancient world." Waves of migrating peoples passed through the region, leaving behind a mosaic of ethnic and linguistic groups.

Between 2000 B.C.E. and 1200 B.C.E., Indo-European-speaking Aryans from the north are thought to have flooded into northern Afghanistan and then spread south towards India and west towards Persia. They set up a nation that, during the rule of Medes (an ancient Iranian people) and Achaemenid Persians (559 B.C.E. to 338 B.C.E.), became known as Aryānām Xšaθra or Airyānem Vāejah.

Later, during the rule of the Ashkanians (247 B.C.E. to 226 C.E.) and the Sassanians (226 to 651 C.E.), the third and fourth Iranian dynasties, it was called Erānshahr, meaning "Dominion of the Aryans," and included large parts of Mesopotamia, the Caucasus, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iran and modern-day Central Asia (Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and the western part of Pakistan.

Zoroastrianism might have originated in what is now Afghanistan between 1800 to 800 B.C.E. Ancient Iranian languages, such as Avestan, may have been spoken in the region at that time.

By 330 B.C.E., Alexander the Great had invaded Afghanistan and conquered the surrounding regions. After Alexander's brief occupation, the Hellenistic successor states of the Seleucids (311 B.C.E. to 63 B.C.E.) and Greco-Bactrians (250 B.C.E. to 130 B.C.E.) controlled the area, while the Mauryas from India annexed the southeast for a time and introduced Buddhism to the region until the area returned to Bactrian rule.

During the first century C.E., the Buddhist Tocharian Kushans created a vast empire there but were defeated by the Sassanids in the third century, who ruled up to the seventh century, when they were conquered by Muslim Arab armies at the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah. The Arab Abbasids conquered the northwest section of Afghanistan by the ninth century and administered that region as part of Khorasan.

The Samanid empire existed from 875-999, the Muslim Ghaznavid Empire from 977–1187, the Seljukids from 1037–1194, the Ghurids from 1149–1212, and the Timurid Dynasty existed from 1370-1506. The periods of Ghaznavids of Ghazni and Timurids of Herat are considered as some of the most brilliant eras of Afghanistan's history. The strong Sunni Ghaznavid Empire prevented the eastward spread of Shiism from Iran, thereby ensuring that most Muslims in Afghanistan and South Asia remained Sunnis.

In 1219, the region was overrun by the Mongols under Genghis Khan, who devastated the land. Their rule continued with the Ilkhanates, and was extended further following the invasion of Timur Lang, a ruler from Central Asia.

In 1504, Babur, a descendant of both Timur Lang and Genghis Khan, established the Mughal Empire with its capital at Kabul. By the early 1700s, Afghanistan was controlled by several ruling groups: Uzbeks to the north, Safavids to the west and the remaining larger area by the Mughals or self-ruled by local Afghan tribes.

In 1709, Mirwais Khan Hotak, a local Afghan (Pashtun) from the Ghilzai clan, overthrew and killed Gurgin Khan, the Safavid governor of Kandahar Province. Khan had defeated the Persians, who were attempting to convert the Kandahar population to the Shia sect of Islam. Mirwais held Kandahar until his death in 1715 and was succeeded by his son Mir Mahmud Hotaki. In 1722, Mir Mahmud led an army to Isfahan (now in Iran), sacked the city and proclaimed himself Shah of Persia.

In 1738, Nadir Shah and his army, which included four thousand Pashtuns, conquered Kandahar, and occupied Ghazni, Kabul, and Lahore. In 1747, Nadir Shah was assassinated. In that year, one of Nadir's commanders and personal bodyguard, Ahmad Shah Abdali, a Pashtun from the Abdali clan, called for a Loya Jirga (Council of Elders) at which Ahmad Shah was chosen as king. He changed his title and clan name to “Durrani.”

By 1751, Ahmad Shah Durrani and his Afghan army conquered the entire present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, Khorasan and Kohistan provinces of Iran, along with Delhi in India. In October 1772, Ahmad Shah retired to his home in Maruf, Kandahar, where he died peacefully. He is regarded as the founder of modern Afghanistan. He was succeeded by his son, Timur Shah Durrani, who transferred the capital from Kandahar to Kabul. Timur died in 1793 and was succeeded by his son Zaman Shah Durrani.

During the nineteenth century, Afghanistan struggled successfully against the colonial powers and served as a buffer state between Russia and British India. The three Anglo-Afghan wars (1839–1842, 1878–1880, and 1919) could have forged national unity, were it not for internal conflict. Much territory and autonomy was ceded to the United Kingdom. It was not until King Amanullah Khan acceded to the throne in 1919 that Afghanistan regained control of its foreign affairs. During the period of British intervention, ethnic Pashtun territories were divided by the Durand Line, leading to strained relations between Afghanistan and British India—and later the new state of Pakistan.

Forty years of stability, the longest in Afghanistan’s history, occurred between 1933 and 1973, under the rule of Mohammed Zahir Shah. However, in 1973, Zahir Shah's brother-in-law, Sardar Daoud Khan launched a bloodless coup. Daoud Khan and his entire family were murdered in 1978, when the communist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan launched a coup known as the Great Saur Revolution and took over the government. Many of the communists were young, recently urbanized, de-tribalized people seeking social advancement.

Opposition against, and conflict within, the series of communist governments that followed was considerable. As part of a Cold War strategy, in 1979 the United States government under President Jimmy Carter began to covertly fund and train anti-government Mujahideen forces, which were discontented Muslims who opposed the official atheism of the Marxist regime. To help communist forces, the Soviet Union intervened on December 24, 1979. Between 110,000 to 150,000 Soviet troops, assisted by another 100,000 pro-communist Afghan troops, were in Afghanistan.

Over five million Afghans moved into refugee camps in neighboring Pakistan, Iran, and other countries. More than three million settled in Pakistan, over a million in Iran and many others in different countries. Faced with mounting international pressure and the loss of over 15,000 Soviet soldiers as a result of Mujahideen opposition forces trained by the United States, Pakistan, and other foreign governments, the Soviets withdrew ten years later, in 1989.

The Soviet withdrawal was seen as an ideological victory in the United States, which had backed the Mujahideen through three U.S. presidential administrations to counter Soviet influence in the vicinity of the oil-rich Persian Gulf. But when Soviet forces left, the U.S. and its allies lost interest and did little to help rebuild the war-ravaged country. The USSR continued to support President Najibullah until his downfall in 1992, but the absence of Soviet forces resulted in the downfall of the pro-communist government.

A leadership vacuum then appeared. Fighting continued among the Mujahideen factions, facilitating the rise of warlords. The most serious fighting occurred in 1994, when over 10,000 people were killed in Kabul. The chaos and corruption that dominated post-Soviet Afghanistan helped the rise of the Taliban, who were mostly Pashtuns from the Helmand province and Kandahar region.

The Taliban developed as a political-religious force, and seized Kabul in 1996. By the end of 2000, the Taliban were able to capture 95 percent of the country, aside from the opposition (Afghan Northern Alliance) strongholds primarily found in the northeast corner of Badakhshan Province. The Taliban sought to impose a strict interpretation of Islamic Sharia law and were later implicated as supporters of terrorists, most notably by harboring Osama bin Laden's Al-Qaeda network. During the Taliban's seven-year rule, women were banned from jobs and girls were forbidden to attend schools or universities. Those who resisted were punished instantly. Communists were systematically eradicated and thieves were punished by the cutting off a hand or foot.

Following the September 11, 2001 attacks in which the World Trade Center in New York was destroyed and the Pentagon was damaged, killing more than 3,000 people, the United States launched Operation Enduring Freedom, a military campaign to destroy the Al-Qaeda terrorist network operating in Afghanistan and overthrow their host (the Taliban government). The U.S. made common cause with the Afghan Northern Alliance to achieve its ends.

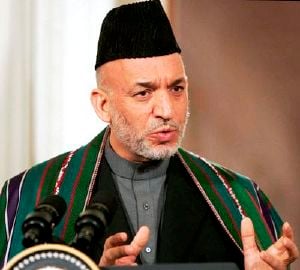

In December 2001, major leaders from the Afghan opposition groups and diaspora met in Bonn, Germany, and agreed on a plan for the formulation of a new democratic government that resulted in the inauguration of Hamid Karzai, a Pashtun from the southern city of Kandahar, as chairman of the Afghan Interim Authority.

After a nationwide Loya Jirga in 2002, Karzai was chosen to assume the title as interim-president of Afghanistan. In 2003, the country convened a constitutional Loya Jirga and ratified a new constitution the following year. Hamid Karzai was elected president in a nationwide election in October 2004. Legislative elections were held in September 2005. The National Assembly—the first freely elected legislature in Afghanistan since 1973—sat in December 2005, and was noteworthy for the inclusion of women as voters, candidates, and elected members.

As the country continued to rebuild, by 2007 it was struggling against poverty, poor infrastructure, large concentrations of land mines and other unexploded ordinance on earth, as well as a huge illegal opium poppy cultivation and opium trade. Afghanistan remains subject to occasionally violent political jockeying and continues to grapple with the Taliban insurgency.

Following the withdrawal of NATO troops in 2021, the Taliban launched a massive military offensive in May 2021, allowing the Islamic Emirate to take control of the country over the following three and a half months. The Afghan Armed Forces rapidly disintegrated. The republic collapsed on August 15, 2021, when Taliban forces entered Kabul and Afghan President Ashraf Ghani fled the country.

Politics and government

Politics in Afghanistan has consisted of power struggles, bloody coups, and unstable transfers of power. With the exception of a military junta, the country has been governed by nearly every system of government over the past century, including a monarchy, republic, theocracy, and communist state. The constitution ratified by the 2003 Loya Jirga restructured the government as an Islamic republic consisting of three branches: executive, legislature, and judiciary.

Afghanistan was an Islamic republic consisting of three branches, the executive, legislative, and judicial. The nation was led by President Ashraf Ghani with Amrullah Saleh and Sarwar Danish as vice presidents. The National Assembly was the legislature, a bicameral body having two chambers, the House of the People and the House of Elders. The Supreme Court was led by Chief Justice Said Yusuf Halem, the former Deputy Minister of Justice for Legal Affairs. It was administratively divided into 34 provinces (wilayat), each with a presidentially appointed governor and a capital.

After the withdrawal of NATO troops in 2021, the Taliban launched an offensive against the government and within a few months regained control of the country. The President and Vice Presidents fled into exile on August 15, 2021.

Economy

The economy improved significantly since the fall of the Taliban regime in 2001, largely because of international help, the recovery of the agricultural sector, and service-sector growth.

Despite the progress of the past few years, Afghanistan is extremely poor, landlocked, and highly dependent on foreign aid, agriculture, and trade with neighboring countries. Much of the population continues to suffer from shortages of housing, clean water, electricity, medical care, and jobs. Crime, insecurity, and the Afghan government's inability to extend rule of law to all parts of the country pose challenges to future growth.

While the international community remains committed to Afghanistan's development, pledging over $24 billion at three donors' conferences since 2002, it will need to overcome a number of challenges. Expanding poppy cultivation and a growing opium trade generate roughly $3 billion in illicit economic activity and looms as one of Kabul's most serious policy concerns. As much as one-third of Afghanistan's GDP comes from opium, its two derivatives, morphine and heroin, as well as hashish production. Other challenges include budget sustainability, job creation, corruption, government capacity, and rebuilding war-torn infrastructure. Severe drought in 1998–2001 added to the nation's difficulties.

One of the main drivers for economic recovery is the return of over four million refugees, who brought with them fresh energy, entrepreneurship, and wealth-creating skills as well as much needed funds to start businesses.

Afghanistan may possess up to 36 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, 3.6 billion barrels of petroleum, and up to 1.33 billion barrels of natural gas liquids. Sales of natural gas, first tapped in 1967, peaked during the 1980s at $300 million a year in export revenues (56 percent of the total). Ninety percent of these exports went to the Soviet Union to pay for imports and debts. When Soviet troops withdrew in 1989, Afghanistan's natural gas fields were capped to prevent sabotage. Other reports suggest that the country has huge amounts of gold, copper, coal, iron ore, and other rich minerals.

The Afghan economy continues to be overwhelmingly agricultural, despite the fact that only 12 percent of its total land area is arable and less than 6 percent is cultivated. Eighty percent of the workforce is involved in agriculture that is constrained by erratic winter snows and spring rains. Irrigation is primitive. Relatively little use is made of machines, chemical fertilizer, or pesticides. Current agricultural practices in Afghanistan combine cultivation and animal husbandry. Wheat is the principal crop, followed by rice, barley, and corn. The main cash crops are almonds and fruits. Cotton was a key export until the civil war. Large areas of land have been converted to poppy cultivation for the heroin trade.

Opium-derived revenues constituted a big source of income for both sides during the civil war. The Taliban earned roughly $4 million per year on opium taxes alone. Opium is easy to produce and transport, and Afghanistan has been the world's largest producer of opium for the past decade. In 2000, the Taliban banned opium poppy cultivation partly to attract foreign aid and, allegedly, having large stockpiles, could control the opium market and create large price increases. While cultivation of opium poppy was eliminated in Taliban-controlled areas, drug trafficking continued. In 2001, the Taliban allowed poppy cultivation to resume. Much of the opium production is refined into heroin. The post-Taliban Afghanistan government enacted counter-narcotics policies and programs.

Kabul International Airport is a hub to Ariana Afghan Airlines, which is the national airlines carrier of Afghanistan. The country has four international airports: Hamid Karzai International Airport (formerly Kabul International Airport), Kandahar International Airport, Herat International Airport, and Mazar-e Sharif International Airport. There are an additional 39 domestic airports. Bagram Air Base is a major military airfield.

The country has three rail links: one, a 75-kilometer (47 mi) line from Mazar-i-Sharif to the Uzbekistan border; a 10-kilometer (6.2 mi) long line from Toraghundi to the Turkmenistan border (where it continues as part of Turkmen Railways); and a short link from Aqina across the Turkmen border to Kerki. These lines are used for freight only and there is no passenger service.

Private vehicle ownership increased substantially since the early 2000s. Taxis are yellow in color and consist of both cars and auto rickshaws. In rural Afghanistan, villagers often use donkeys, mules, or horses to transport or carry goods. Camels are primarily used by the Kochi nomads. Bicycles are popular throughout Afghanistan.

Afghanistan has rapidly increased in communication technology, and has embarked on wireless companies, internet, radio stations, and television channels. Afghan telecommunication companies, Afghan Wireless, Roshan (Telecom), and Areeba, boasted increases in rapid cellular phone use.

Exports include opium, fruits and nuts, hand-woven carpets, wool, cotton, hides and pelts, and precious and semi-precious gems. Export partners include the United States, Pakistan, India, and Finland.

Imports commodities include capital goods, food, textiles and petroleum products. Import partners include Pakistan, United States, Germany, India, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Russia, and Kenya.

Since the Taliban's takeover of the country in August 2021, the United States has frozen about $9 billion in assets belonging to the Afghan central bank, blocking the Taliban from accessing billions of dollars held in U.S. bank accounts. Western nations have suspended most humanitarian aid to Afghanistan following the Taliban's takeover of the country.

Demographics

Afghanistan is an ethnically and linguistically mixed country, reflecting its location astride historic trade and invasion routes leading from Central Asia into South and Southwest Asia.

Ethnic groups

Generally the four major ethnic groups are the Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras and Uzbeks. A further 10 other ethnic groups are recognized. Pashtuns are the largest ethnic group, accounting for about 42 percent of the population of 31,056,997 (a 2006 estimate). Tajiks (27 percent), Hazara (9 percent), Uzbeks (9 percent), Aimaq (4 percent), Turkmen people (3 percent), Baluch (2 percent), and other small groups (4 percent) make up the remainder. Figures are approximations because a systematic census has not been held in the country in decades.

The term Afghan, historically synonymous with Pashtun, is used to describe a person from the country of Afghanistan. Afghans draw their national identity from the founding of the Durrani Empire in the mid-eighteenth century. Ahmed Shah Durrani and his sons and grandsons were the first Pashtun rulers. The Pashtuns (also known as Pakhtun or Pathan) are independent people that reside mainly in southern and eastern Afghanistan and in western Pakistan. Smaller groups are found in Iran and India. Pashtun culture is ancient.

The Persian-speaking Tajiks are closely related to the Persians of Iran. They can trace their roots back to the original eastern Iranian peoples, such as the Bactrians, Sogdians, Scythians, and Parthians, as well as ancient Persians who fled to Central Asia during the Arab Islamic expansion. The Tajiks also comprise the majority population of Tajikistan and are found in large numbers in Uzbekistan and Iran as well as parts of northwest Pakistan and the Xinjiang province of China.

The Hazara seem to have Turkic-Mongol origins, mixed with some Caucasoid. The Hazara speak Persian, with more Mongolian words, and many Afghans believe the Hazara are descendants of Genghis Khan's army that invaded during the twelfth century.

The Uzbeks are the main Turkic people found in Afghanistan and are found in the northern regions. The Uzbeks most likely migrated with Turkic invaders and intermingled with Iranian tribes. Most Uzbeks are Sunni Muslim and are usually bilingual, fluent in both Persian and Uzbek.

The Turkmen people are the smaller Turkic group who can be found in neighboring Turkmenistan. Largely Sunni Muslim, they arrived with Turkic invaders, and are traditionally nomadic (though they were forced to abandon this way of life in Turkmenistan itself under Soviet rule).

The Baluch are another Iranian ethnic group that numbers around 200,000, mostly residing in southern Afghanistan. The main Baluch areas are Baluchistan province in Pakistan and the Sistan and Baluchistan province of Iran. Likely an offshoot of the Kurds, they reached Afghanistan sometime between 1300 and 1000 B.C.E. Mainly pastoral and desert dwellers, the Baluch are Sunni Muslim.

The Nuristani are an Indo-Iranian people, who live in the isolated northeast. Better known as the Kafirs, they were forcibly converted to Islam during the rule of "Iron" Amir Abdur Rahman and their country was renamed Nuristan. Many Nuristanis believe that they descend from Alexander's Greeks, but there is no genetic evidence for this. They are largely Sunni Muslims.

Religion

Ninety-nine percent of Afghanistan's population adheres to Islam. An estimated 80 percent of the population is Sunni, following the Hanafi school of jurisprudence; 19 percent is predominantly Shi'a. Despite attempts during the years of communist rule to secularize Afghan society, Islamic practices pervade all aspects of life. In fact, Islam served as the principal basis for expressing opposition to communist rule and the Soviet invasion. Likewise, Islamic religious tradition and codes, together with traditional practices, provide the principal means of controlling personal conduct and settling legal disputes. Excluding urban populations, most Afghans are divided into tribal and other kinship-based groups, which follow traditional customs and religious practices.

There are about 30,000 to 150,000 Hindus and Sikhs living in different cities, but mostly in Jalalabad, Kabul, and Kandahar. Also, there was a small Jewish community in Afghanistan that fled the country after the 1979 Soviet invasion.

Women in society

In the 1920s, King Amanullah tried to promote female empowerment, and under communist rule, many women were able to study in universities. The strict Islamic orthodoxy of the Taliban required women to be covered by a long veil and accompanied by a male relative should they leave the house. Women faced obstacles to work, to study, or to obtain access to health care. Women were required to be modest and obey the orders of their fathers, brothers, and husbands. In the post-Taliban Islamic republic, women delegates have been elected to parliament and Kabul University has readmitted woman students.

Marriage and the family

In Afghan society, marriage is considered an obligation, and divorce is rare and stigmatized. Polygamy is allowed, but is uncommon. The pattern is to marry kin, and numerous cousins marry. Often, the first contacts for prospective marriage partners are made discreetly by women. The two families] negotiate the financial aspects and decide on the trousseau, the bride price, and the dowry. There is an official engagement, when the groom’s female relatives bring gifts to the bride. The wedding is a three-day party, paid for by the groom's family, when the marriage contract is signed and the couple is brought together. A lavish procession brings the bride to her new home. Lower social groups give their daughters in marriage to higher social groups.

The traditional household consists of a man, his wife, his sons with their spouses and children, and his unmarried daughters. Domestic units are larger among tribal people than among urban dwellers. When a man dies, the sons can decide to stay together or divide the family assets. Financial ability, other skills, and prestige rather than age determines authority among brothers. To avoid splitting up family property, brothers may decide to own it jointly or to be compensated financially. Women do not inherit land, real estate, or livestock.

Descent is through the male line, and each tribal group is divided into subtribes, clans, lineages, and families. Genealogy establishes inheritance, mutual obligations, and a feeling of solidarity. Disputes over women, land, and money may result in blood feuds. The tribal system is particularly developed among the Pashtuns, and is potent in political terms. Men feel a fierce loyalty to their own tribe, such that, if called upon, they would assemble in arms under the tribal chiefs and local clan leaders (Khans). Under Islamic law, every believer has an obligation to bear arms at the ruler's call (Ulul-Amr). However, many inhabitants do not belong to a tribe or are loosely connected to one. Marriage and neighborhood links can be stronger than extended kinship.

Grazing land is held communally, but agricultural land is privately owned. Most of the population consists of small landholders who supplement their income by sending a family member to work in the city or abroad. Non-land-owning farmers can become tenants or work for others. Often in debt, they are dependent on headmen and landlords.

Language

Pashto and Persian (Dari) are both official languages of the country. Persian is spoken by at least half of the population and serves as a lingua franca for most Afghans. Pashto is spoken by 35 percent of the population, mainly in the south, east, and southwest. Uzbek and Turkmen are unofficial languages that are spoken in the north. Smaller groups throughout the country also speak more than 70 other languages and numerous dialects. Bilingualism is common.

Status

There are big differences in wealth and social status in Afghan society, which is stratified along religious and ethnic lines. Members of the king's family were ministers and ambassadors during the twentieth century. Civil servants were Persian-speaking urban residents. Ismaelis and Shiites (especially the Hazaras) had the lowest status. Pashtuns held most administrative posts in the provinces. The richest landlords and village headmen dominated local communities. The Sayyeds, believed to be the descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, played a role as mediators. Traditional leaders have lost their preeminence to military commanders and young religious militants. Smugglers can often become rich.

Culture

Afghans display pride in their religion, country, ancestry, and above all, their independence. Like other highlanders, Afghans are regarded with mingled apprehension and condescension, for their high regard for personal honor, for their clan loyalty, and for their readiness to carry and use arms to settle disputes. As clan warfare and internecine feuding has been one of their chief occupations since time immemorial, this individualistic trait has made it difficult for foreign invaders to hold the region.

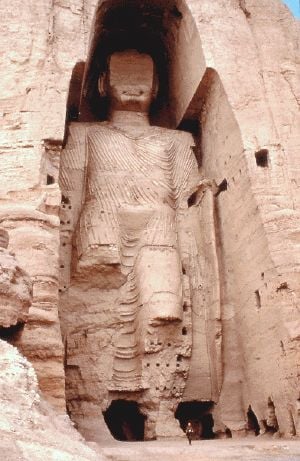

Many of the country's historic monuments have been damaged in recent wars. The Taliban destroyed the two famous statues of Buddha in the Bamyan Province, which they regarded as idolatrous. (The statues are now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and there are plans in place to rebuild them.) Other famous sites include the cities of Kandahar, Herat, Ghazni, and Balkh. The Minaret of Jam, in the Hari Rud valley, is also a World Heritage Site. The cloak worn by Muhammad is stored inside the famous Khalka Sharifa in Kandahar City.

Housing

Afghan houses are traditionally made of a series of rooms located around a private rectangular courtyard where women and children play, cook, and socialize. Married sons share the same house as their parents, although they have separate quarters. Some Afghan houses contain a special room where men socialize with each other. In the cities, many Afghans live in apartments. Nomads live in tents.

Food

Everyday food consists of flat bread cooked on an iron plate in a fire or clay oven, often dipped in a light meat stock. Yogurt, butter, cream, and dried buttermilk feature in the diet, as do onions, peas and beans, dried fruits, and nuts. Rice is eaten in some areas and in urban settlements. Scrambled eggs prepared with tomatoes and onions are a common meal. Food is cooked with various types of oils, including the fat of a sheep's tail. Tea is drunk all day. Other drinks include water and buttermilk. Afghans use the right hand to eat from a common bowl on the floor. There are numerous small restaurants that serve as teahouses and inns.

The common Islamic food prohibitions are observed. Meat is only eaten from animals that are slaughtered according to Islamic law. Alcohol, pork, and wild boar are not consumed. On special occasions, pilau rice is served with meat, carrots, raisins, pistachios, or peas. The preferred meat is mutton, but chicken, beef, and camel also are consumed. Kebabs, fried crepes filled with leeks, ravioli, and noodle soup also are prepared.

Clothing

Traditional male Afghani clothing usually includes a pakol (hat), lungee (turban), and a chapan (coat). Traditional dress for women includes two-piece outfits consisting of loose trousers worn under a tunic with a high neck and long sleeves. The clothes are fitted loosely at the waist and extend below the knees, with the straight skirt slit up both sides for ease of movement. Many women complete the outfit with a long scarf gracefully draped across the shoulders. More elaborate and fancier clothing are dresses adorned with gold threading and silk fabrics in many different colors. These are usually worn at special occasions such as weddings.

Child rearing

Babies are wrapped tightly and placed in wooden cradles, with a drain for urine, or carried by the mother in a shawl. They may be breastfed for two years. Children are cared for by female relatives, and learn early that no one will intervene when they cry or are hurt. They are physically punished, and are taught to respect and obey elderly persons. Independence, individual initiative, and self-confidence are praised. Boys are circumcised at age seven. Boys are taught about hospitality, as well as looking after the livestock or a shop. Girls help their mothers as soon as they can stand. Both boys and girls are taught the values of honor and shame, and when to show pride or remain modest.

Education

In 2003, it was estimated that 30 percent of Afghanistan's 7,000 schools had been very seriously damaged during more than two decades of civil war. Only half of the schools had clean water, while fewer than 40 percent had adequate sanitation. Education for boys was not a priority during the Taliban regime, and girls were banished from schools outright.

Education was revitalized after the fall of the Taliban. Primary education, which is free and available for all boys and girls, lasts six years. If the student does well on the entrance exam, they are then admitted into secondary education, which is divided into ages seven to nine and ages 10 to 12.

Kabul University reopened to both male and female students, and in 2006, the American University of Afghanistan opened, accepting students from Afghanistan and neighboring countries. Other tertiary institutes include the University of Islamic Studies, Balk University, an agricultural institute and a polytechnic, a state medical institute, and two teacher training institutes.

When the Taliban returned to power in 2021 there were concerns that access to education, especially for the female population, would be heavily set back. Though the Taliban claimed that it respected their rights, they barred girls and female teachers from returning to secondary schools. They are also developing a new curriculum for all students.

Scientists

Numerous Persian scientists originated in Afghanistan. Most notable was Avicenna (Abu Alī Hussein ibn Sīnā), who traveled to Isfahan to establish a medical school, and is known by some scholars as "the father of modern medicine." Dubbed "the most famous scientist of Islam," his most famous works are The Book of Healing and The Canon of Medicine.

Literature

Although literacy levels are low, classic Persian poetry plays an important role in Afghan culture. Private poetry competition events known as “musha’era” are quite common even among ordinary people. Almost every home owns one or more poetry collection of some sort, even if it is not read often. Many of the famous Persian poets of the tenth to fifteenth centuries stem from Khorasan. They were scholars in many disciplines such as languages, natural sciences, medicine, religion, and astronomy. They include:

- Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi, who was born and educated in Balkh in the thirteenth century and moved to Konya in modern-day Turkey

- Rabi'ah Quzdari, the first Persian poetess, a tenth-century native of Balkh

- Abu Mansur Daqiqi, a tenth-century native of Balkh)

- Farrukhi Sistani, a tenth-century Ghaznavids royal poet

- Khwaja Abdullah Ansari, an eleventh-century native of Herat

- Sanaayi, a twelfth-century native of Ghazni

- Jāmī of Herāt, a fifteenth-century native of Heart

- Alisher Navoi, a fifteenth-century native of Herat.

Afghanistan's poetry is primarily written in Persian and—to a lesser degree—in Pashto. The most famous forms of poetry in Afghanistan are Ghazal and Charbeiti, both of which were originally unique to the Persian language but have since been used by other languages. Charbeiti is told in four lines and usually describes love, youth, war, or events in the poet's life, and are passed on orally.

Contemporary Persian-language poets and writers include Ustad Betab, Qari Abdullah, Khalilollah Khalili, Sufi Ghulam Nabi Ashqari, Qahar Asey, Parwin Pazwak, and others. In 2003, Khaled Hosseini published “The Kiterunner” which, though fiction, captured much of the history, politics, and culture experienced in Afghanistan from the 1930s to present day.

Art

The most famous type of Afghan art is Gandhara art, done between the first century and seventh century C.E., which is based on Greco-Buddhist art. Since the 1900s, Afghanistan began to use Western techniques in art. Afghanistan's art was originally almost entirely done by men, but recently in theater arts women have begun to take center stage. Art is largely centered at the Kabul Museum. Afghanistan is known for making beautiful and unique rugs.

Music

Before the Taliban gained power, the city of Kabul was home to many musicians who were masters of both traditional and modern Afghan music, especially during the Nauroz celebration. Kabul in the middle part of the twentieth century has been likened to Vienna during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Since the 1980s, Afghanistan has been involved in near constant violence. As such, music has been suppressed and recording for outsiders minimal. During the 1990s, the Taliban government banned instrumental music. In spite of arrests and destruction of musical instruments, Afghan musicians have continued to ply their trade.

Qur’an recitation is an important kind of unaccompanied religious performance, as is the ecstatic Zikr ritual of the Sufis, which uses songs called na't, and the Shi'a solo and group singing styles like mursia, manqasat, nowheh, and rowzeh. The Chishti Sufi sect of Kabul is an exception in that they use instruments like the rubab, tabla, and armonia in their worship; this music is called gaza-yeh ruh (“food for the soul”).

Wedding music is a vital part of Afghan folk music. Wedding parties are usually segregated by gender. Men are usually entertained by a male singer with a dhol or tabla drum, while accompaniment is typically a rubab or tambur. The songs are most typically pop or ghazal. Women usually sing and dance with dayra, a type of drum common in Afghanistan.

Afghan songs are typically about love, and use symbols like the nightingale and rose, and refer to folklore like the Leyla and Majnoon story. They do not discuss current issues of any nature. Afghanistani folk instruments include the ghaychak, dutar, rubab, zerbaghali, flute, and cymbals.

The classical musical form of Afghanistan is called klasik, which includes both instrumental and vocal ragas, as well as Tarana and Ghazals. Many "ustads," or professional musicians, have learned North Indian classical music in India, and some of them were Indian descendants who moved from India to the royal court in Kabul in the 1860s. They maintain cultural and personal ties with India and they use the Hindustani musical theories and terminology, for example raga (melodic form) and "tala" (rhythmic cycle).

Modern popular music did not arise until the 1950s when radio became commonplace. They used orchestras featuring both Afghan and Indian instruments, as well as European clarinets, guitars, and violins. The 1970s were the golden age of Afghanistan's music industry. Popular music also included music imported from Iran, Tajikistan, and elsewhere.

Sports

The people of Afghanistan are prominent horsemen, as the national ancient sport is Buzkashi, similar to polo, but in which a goat carcass is used instead of a ball. Afghan hounds (a type of running dog) also originated from Afghanistan. Most official Afghan sports are run by the Afghan Sports Federation, which promotes soccer, basketball, volleyball, track, bowling, and chess.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 CIA, Afghanistan World Factbook. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ↑ Afghanistan Human Development Indicators. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ghubār, Ghulām Muḥammad, and Sherief A. Fayez. Afghanistan in the Course of History. Herndon, VA: All Prints, 2001.

- Griffiths, John Charles. Afghanistan: A History of Conflict. London: Carlton Books, 2001. ISBN 1842225979

- Levi, Peter. The Light Garden of the Angel King: Journeys in Afghanistan. Collins, 1972. ISBN 0002110423

- Moorcroft, William, George Trebeck, and H. H. Wilson. Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Panjab, in Ladakh and Kashmir, in Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz, and Bokhara from 1819 to 1825. New Delhi: Sagar Publications. Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0195771990

- Rashid, Ahmed. Taliban: Islam, Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia. New York: I.B. Tauris, 2002. ISBN 1860648304

- Singer, André, Toby Molenaar, and Michael Freeman. Guardians of the Northwest Frontier: The Pathans. Time-Life Books, 1982. ISBN 0705407020

- Toynbee, Arnold Joseph. Between Oxus and Jumna. New York: Oxford University Press, 1961. ISBN 0192152262

- Wood, John, and Alexander Wood. A Journey to the Source of the River Oxus. Gregg Division McGraw-Hill, 1971. ISBN 0576033227

- Vogelsang, Willem. The Afghans. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0631198415

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2023.

- Afghanistan Online

- Afghanistan CIA World Factbook

- Afghanistan Countries and Their Cultures

- Afghanistan country profile BBC

- Afghanistan Law Library of Congress

- Afghanistan Infoplease

- Afghanistan, Opium and the Taliban

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.