Bread

Bread is a staple food prepared from a dough of flour (usually wheat) and water, usually by baking. It is one of the oldest human-made foods, having been of significance since the dawn of agriculture, and plays an essential role in both religious rituals and secular culture. Bread continues to be an important part of the diet of people in many cultures around the world.

Bread may be leavened by naturally occurring microbes (e.g. sourdough), chemicals (e.g. baking soda), or industrially produced Baker's yeast, all of which create bubbles before baking to produce a lighter, more easily chewed bread. Unleavened bread is prepared without using rising agents; consequently they are generally flat breads, although not all flat breads are unleavened. In many countries, commercial bread often contains additives to improve flavor, texture, color, shelf life, nutrition, and ease of production. While commercially produced bread is convenient and cheap, many people still enjoy baking their own bread, carrying on their family and cultural traditions.

Etymology

The Old English word used for bread was hlaf (hlaifs in Gothic: modern English loaf), which appears to be the oldest Teutonic name.[1] Old High German hleib and modern German Laib derive from this Proto-Germanic word. Thus khleb, (bread) from an earlier khleiba from Gothic hlaifs and the more ancient form hlaibhaz, meant bread baked in an oven (and, probably, made with yeast); distinguished from a l-iepekha, which was a flat cake molded (liepiti) from paste, and baked on charcoal. The same nominal stem *hlaibh- has been preserved in modern English as loaf.[2]

By around 1200, Old English "bread" (bit, crumb, morsel), cognate with Old Norse brauð, Danish brød, Old Frisian brad, Middle Dutch brot, Dutch brood, and German Brot, had replaced hlaf as the usual Old English word for bread.[1]

History

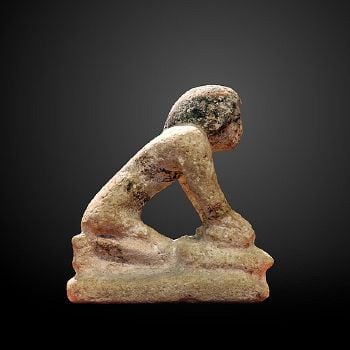

Bread is one of the oldest prepared foods. Evidence from 30,000 years ago in Europe and Australia revealed starch residue on rocks used for pounding plants.[3][4] It is possible that during this time, starch extract from the roots of plants, such as cattails and ferns, was spread on a flat rock, placed over a fire and cooked into a primitive form of flatbread.

The oldest evidence of actual bread-making has been found in a 14,500-year-old Natufian site in Jordan's northeastern desert, where a large circular stone fireplace within which charred bread crumbs showing signs of grinding, sieving, and kneading were found.[5][6]

Around 10,000 B.C.E., with the dawn of the Neolithic age and the spread of agriculture, grains became the mainstay of making bread. Yeast spores are ubiquitous, including on the surface of cereal grains, so any dough left to rest leavens naturally.[7]

An early leavened bread was baked as early as 6000 B.C.E. in southern Mesopotamia, cradle of the Sumerian civilization, who may have passed on the knowledge to the Egyptians around 3000 B.C.E. The Egyptians refined the process and started adding yeast to the flour. The Sumerians were already using ash to supplement the dough as it was baked.[8]

There were multiple sources of leavening available for early bread. Airborne yeasts could be harnessed by leaving uncooked dough exposed to air for some time before cooking. Pliny the Elder reported that the Gauls and Iberians used the foam skimmed from beer, called barm, to produce "a lighter kind of bread than other peoples." Parts of the ancient world that drank wine instead of beer used a paste composed of grape juice and flour that was allowed to begin fermenting, or wheat bran steeped in wine, as a source for yeast. The most common source of leavening was to retain a piece of dough from the previous day to use as a form of sourdough starter.[9] as Pliny also reported this method: "Generally however they do not heat it up at all, but only use the dough kept over from the day before; manifestly it is natural for sourness to make the dough ferment."[10]

Sliced bread

Sliced bread is a loaf of bread that has been sliced with a machine and packaged for convenience, as opposed to the consumer cutting it with a knife. It was first sold in 1928, advertised as "the greatest forward step in the baking industry since bread was wrapped."[11]

Otto Frederick Rohwedder of Davenport, Iowa invented the first single loaf bread-slicing machine. A prototype he built in 1912 was destroyed in a fire,[12] and it was not until 1928 that Rohwedder had a fully working machine ready. The first commercial use of the machine was by the Chillicothe Baking Company of Chillicothe, Missouri, who sold their first slices on July 7, 1928. Their product, "Kleen Maid Sliced Bread", proved to be a success. The bread was advertised as "the greatest forward step in the baking industry since bread was wrapped."[13]

St. Louis baker Gustav Papendick bought Rohwedder's second bread slicer and set out to improve it by devising a way to keep the slices together at least long enough to allow the loaves to be wrapped.[12] After failures trying rubber bands and metal pins, he settled on placing the slices into a cardboard tray. The tray aligned the slices, allowing mechanized wrapping machines to function.[14]

In the United Kingdom, the first slicing and wrapping machine was installed in the Wonderloaf Bakery in Tottenham, London, in 1937. By the 1950s around 80 percent of bread sold in Britain was pre-sliced.[15]

Chorleywood bread process

The Chorleywood bread process was developed by Bill Collins, George Elton, and Norman Chamberlain of the British Baking Industries Research Association at Chorleywood in 1961. Compared to traditional bread-making processes, this method uses more yeast, added fats, chemicals, and high-speed mixing to allow the dough to be made with lower-protein wheat, and produces bread in a shorter time. The intense mechanical working of dough dramatically reduces the fermentation period and thus the time taken to produce a loaf. The process is now widely used around the world in large factories. As a result, bread can be produced very quickly and at low costs to the manufacturer and the consumer. However, there has been some criticism of the effect on nutritional value.[16]

Issues have also been reported both with taste and digestion: "Modern bread doesn't taste of bread. If it's not allowed to rise and prove naturally then it doesn't develop the proper taste."[16] As a result, many small bakers offer artisanal bread baked the traditional way. For some consumers, the taste of homemade bread outweighs the extra effort compared to purchasing industrially produced bread, especially with the advent of bread machines.

Cultural significance

Bread is the staple food of the Middle East, Central Asia, North Africa, Europe, and in European-derived cultures such as those in the Americas, Australia, and Southern Africa. This is in contrast to parts of South and East Asia, where rice or noodles are the staple.

Bread has a significance beyond mere nutrition in many cultures because of its history and contemporary importance. Bread is also significant in Christianity as one of the elements (alongside wine) of the Eucharist,[17] and in other religions including Wicca.[18]

In many cultures, bread is a metaphor for basic necessities and living conditions in general. For example, a "bread-winner" is a household's main economic contributor and has little to do with actual bread-provision. This is also seen in the phrase "putting bread on the table." The term "breadbasket" denotes an agriculturally productive region. The Roman poet Juvenal satirized superficial politicians and the public as caring only for "panem et circenses" (bread and circuses).[19] In Russia in 1917, the Bolsheviks promised "peace, land, and bread."[20] In parts of Northern, Central, Southern and Eastern Europe bread and salt is offered as a welcome to guests.[21] In India, life's basic necessities are often referred to as "roti, kapra aur makan" (bread, cloth, and house).[22]

Words for bread, including "dough" and "bread" itself, are used in English-speaking countries as synonyms for money.[1] A remarkable or revolutionary innovation, like the bread-slicing machine, may be called the best thing since "sliced bread."[23] The expression "to break bread with someone" means "to share a meal with someone."[24] The English word "lord" comes from the Anglo-Saxon hlāfweard, meaning "bread keeper," literally "one who guards the loaves." [25]

Types

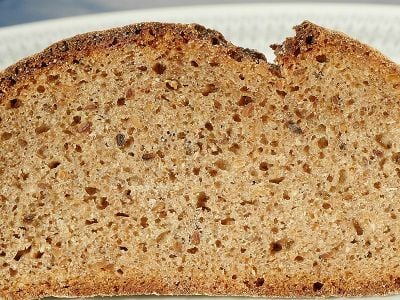

Bread is usually made from a wheat-flour dough that is cultured with yeast, allowed to rise, and baked in an oven. Carbon dioxide and ethanol vapors produced during yeast fermentation result in bread's air pockets.[26]

Owing to its high levels of gluten (which give the dough sponginess and elasticity), Common wheat (Triticum aestivum), also known as bread wheat, is the most common grain used for the preparation of bread.[27] Durum wheat is also used to make bread, although it is more often used in making pasta.

Bread is also made from the flour of other wheat species (including spelt, emmer, einkorn, and kamut): These wheat varieties are commonly referred to as ‘ancient’ grains and are increasingly being used in the manufacture of niche wheat-based food products.[28] Non-wheat cereals including rye, barley, maize (corn), oats, sorghum, millet, and rice have been used to make bread, but, with the exception of rye, usually in combination with wheat flour as they have less gluten.[29]

Gluten-free breads are made using flours from a variety of ingredients such as almonds, rice, sorghum, corn, legumes such as beans, and tubers such as cassava. Since these foods lack gluten, dough made from them may not hold its shape as the loaves rise, and their crumb may be dense with little aeration. Additives such as xanthan gum, guar gum, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), corn starch, or eggs are used to compensate for the lack of gluten.[30]

Preparation

Doughs are usually baked, but in some cuisines breads are steamed (for example, mantou), fried (such as puri), or baked on an unoiled frying pan (like tortillas), or they may be first boiled in water and then baked (like bagels). It may be leavened or unleavened (for example matzo). Salt, fat, and leavening agents such as yeast and baking soda are common ingredients, though bread may contain other ingredients, such as milk, egg, sugar, spice, fruit (such as raisins), vegetables (such as onion), nuts (such as walnut), or seeds (such as poppy).[31]

Methods of processing dough into bread include the straight dough process, the sourdough process, the Chorleywood bread process, and the sponge and dough process.

Formulation

Professional bread recipes are stated using the baker's percentage notation. The amount of flour is denoted to be 100 percent, and the other ingredients are expressed as a percentage of that amount by weight. Measurement by weight is more accurate and consistent than measurement by volume, particularly for dry ingredients. The proportion of water to flour is the most important measurement in a bread recipe, as it affects texture and crumb the most. Hard wheat flours absorb about 62 percent water, while softer wheat flours absorb about 56 percent.[32] Common table breads made from these doughs result in a finely textured, light bread. Most artisan bread formulas contain anywhere from 60 to 75 percent water. In yeast breads, the higher water percentages result in more CO2 bubbles and a coarser bread crumb.

Flour

Flour is grain ground into a powder. It provides the primary structure, starch and protein to the final baked bread. The protein content of the flour is the best indicator of the quality of the bread dough and the finished bread. While bread can be made from all-purpose wheat flour, a specialty bread flour, containing more protein (12–14 percent), is recommended for high-quality bread. If one uses a flour with a lower protein content (9–11 percent) to produce bread, a shorter mixing time is required to develop gluten strength properly. An extended mixing time leads to oxidization of the dough, which gives the finished product a whiter crumb, instead of the cream color preferred by most artisan bakers.[33]

Liquids

Water, or some other liquid, is used to form the flour into a paste or dough. The weight or ratio of liquid required varies between recipes, but a ratio of three parts liquid to five parts flour is common for yeast breads.[34] Recipes that use steam as the primary leavening method may have a liquid content in excess of one part liquid to one part flour. Instead of water, recipes may use liquids such as milk or other dairy products (including buttermilk or yogurt), fruit juice, or eggs. These contribute additional sweeteners, fats, or leavening components, as well as water.[35]

Fats or shortenings

Fats, such as butter, vegetable oils, lard, or that contained in eggs, affect the development of gluten in breads by coating and lubricating the individual strands of protein. They also help to hold the structure together. If too much fat is included in a bread dough, the lubrication effect causes the protein structures to divide. A fat content of approximately 3 percent by weight is the concentration that produces the greatest leavening action.[29] In addition to their effects on leavening, fats also serve to tenderize breads and preserve freshness.

Salt

Salt (sodium chloride) is very often added to enhance flavor and restrict yeast activity. It also affects the crumb and the overall texture by stabilizing and strengthening the gluten.[36] Some artisan bakers forego early addition of salt to the dough, whether wholemeal or refined, and wait until after a 20-minute rest to allow the dough to autolyse.[37]

Leavening

Leavening is the process of adding gas to a dough before or during baking to produce a lighter, more easily chewed bread. Most bread eaten in the West is leavened.[38]

Chemicals

A simple technique for leavening bread is the use of gas-producing chemicals. There are two common methods. The first is to use baking powder or a self-raising flour that includes baking powder. The second is to include an acidic ingredient such as buttermilk and add baking soda; the reaction of the acid with the soda produces gas.[38] Chemically leavened breads are called quick breads and soda breads. This method is commonly used to make muffins, pancakes, American-style biscuits, and quick breads such as banana bread.

Yeast

Many breads are leavened by yeast. The yeast most commonly used for leavening bread is Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the same species used for brewing alcoholic beverages. This yeast ferments some of the sugars producing carbon dioxide. Commercial bakers often leaven their dough with commercially produced baker's yeast. Baker's yeast has the advantage of producing uniform, quick, and reliable results, because it is obtained from a pure culture.[38] Many artisan bakers produce their own yeast with a growth culture. If kept in the right conditions, it provides leavening for many years.[29]

The baker's yeast and sourdough methods follow the same pattern. Water is mixed with flour, salt, and the leavening agent. Other additions (such as spices, herbs, fats, seeds, and fruit) are not needed to bake bread, but are often used. The mixed dough is then allowed to rise one or more times (a longer rising time results in more flavor, so bakers often "punch down" the dough and let it rise again), loaves are formed, and (after an optional final rising time) the bread is baked in an oven.[38]

Many breads are made from a "straight dough", which means that all of the ingredients are combined in one step, and the dough is baked after the rising time;[38] others are made from a "pre-ferment" in which the leavening agent is combined with some of the flour and water a day or so ahead of baking and allowed to ferment overnight. On the day of baking, the rest of the ingredients are added, and the process continues as with straight dough. This produces a more flavorful bread with better texture. Many bakers see the starter method as a compromise between the reliable results of baker's yeast and the flavor and complexity of a longer fermentation. It also allows the baker to use only a minimal amount of baker's yeast, which was scarce and expensive when it first became available. Most yeasted pre-ferments fall into one of three categories: "poolish" or "pouliche", a loose-textured mixture composed of roughly equal amounts of flour and water (by weight); "biga", a stiff mixture with a higher proportion of flour; and "pâte fermentée", which is a portion of dough reserved from a previous batch.[39]

Steam

The rapid expansion of steam produced during baking leavens the bread, which is as simple as it is unpredictable. Steam-leavening is unpredictable since the steam is not produced until the bread is baked. Steam leavening happens regardless of the raising agents (baking soda, yeast, baking powder, sour dough, beaten egg white) included in the mix. The leavening agent either contains air bubbles or generates carbon dioxide. Bacteria and yeast are killed when the temperature rises, halting the generation of CO2. However, the heat vaporizes the water from the inner surface of the bubbles within the dough. The steam expands and makes the bread rise. This is the main factor in the rising of bread once it has been put in the oven.[40]

Sourdough

Sourdough is a type of bread produced by a long fermentation of dough using naturally occurring yeasts and lactobacilli. It usually has a mildly sour taste because of the lactic acid produced during anaerobic fermentation by the lactobacilli. Longer fermented sourdoughs can also contain acetic acid, the main non-water component of vinegar.[41]

Sourdough breads are made with a sourdough starter. The starter cultivates yeast and lactobacilli in a mixture of flour and water, making use of the microorganisms already present on flour; it does not need any added yeast. A starter may be maintained indefinitely by regular additions of flour and water. Some bakers have starters many generations old, which are said to have a special taste or texture.[41] At one time, all yeast-leavened breads were sourdoughs.

Traditionally, peasant families throughout Europe baked on a fixed schedule, perhaps once a week. The starter was saved from the previous week's dough. The starter was mixed with the new ingredients, the dough was left to rise, and then a piece of it was saved to be the starter for next week's bread.[38]

Unleavened bread

Unleavened bread is any of a wide variety of breads which are prepared without using rising agents such as yeast. Unleavened breads are generally flat breads; however, not all flat breads are unleavened. Unleavened breads, such as the tortilla and roti, are staple foods in Central America and South Asia, respectively.

Unleavened breads have symbolic importance in Judaism and Christianity. Jews and Christians consume unleavened breads such as matzo during Passover and Eucharist, respectively, as commanded in Exodus 12:18. The Israelites had to leave Egypt in such a hurry that they could not spare time for their breads to rise; as a reminder, unleavened bread is used in ceremonies.

Properties

Physical-chemical composition

Wheat flour, in addition to its starch, contains three water-soluble protein groups (albumin, globulin, and proteoses) and two water-insoluble protein groups (glutenin and gliadin). When flour is mixed with water, the water-soluble proteins dissolve, leaving the glutenin and gliadin to form the structure of the resulting bread. When relatively dry dough is worked by kneading, or wet dough is allowed to rise for a long time (no-knead bread), the glutenin forms strands of long, thin, chainlike molecules, while the shorter gliadin forms bridges between the strands of glutenin. The resulting networks of strands produced by these two proteins are known as gluten. [42]

Structurally, bread can be defined as an elastic-plastic foam. The glutenin protein contributes to its elastic nature, as it is able to regain its initial shape after deformation. The gliadin protein contributes to its plastic nature, because it demonstrates non-reversible structural change after a certain amount of applied force. Because air pockets within this gluten network result from carbon dioxide production during leavening, bread can be defined as a foam, or a gas-in-solid solution.[7]

Nutritional value

Bread can be a nutritious food and part of any diet. It is a good source of carbohydrates and micronutrients such as magnesium, iron, selenium, and B vitamins. Nutrition experts recommend choosing whole-grain options more often since they provide more vitamins, minerals, and fiber.[43]

Crust

Bread crust is formed from surface dough during the cooking process. It is hardened and browned through the Maillard reaction using the sugars and amino acids due to the intense heat at the bread surface. The crust of most breads is harder, and more complexly and intensely flavored, than the rest. It is rumored to be healthier than the remainder of the bread. Some studies have shown that this is true as the crust has more dietary fiber and antioxidants such as pronyl-lysine. Old wives' tales suggest that eating the bread crust makes a person's hair curlier, however the association is misleading: Wealthy people could afford to eat more bread and curly hair was associated with prosperity, and these two characteristics became associated with each over time. [44]

Culinary uses

Bread can be served at many temperatures; once baked, it can subsequently be toasted. It is most commonly eaten with the hands, either by itself or as a carrier for other foods. Bread can be spread with butter, dipped into liquids such as gravy, olive oil, or soup; it can be topped with various sweet and savory spreads, or used to make sandwiches containing meats, cheeses, vegetables, and condiments.[45]

Bread is used as an ingredient in other culinary preparations, such as the use of breadcrumbs to provide crunchy crusts or thicken sauces; toasted cubes of bread, called croutons, are used as a salad topping; seasoned bread is used as stuffing inside roasted turkey; sweet or savory bread puddings are made with bread and various liquids; egg and milk-soaked bread is fried as French toast; and bread is used as a binding agent in sausages, meatballs, and other ground meat products.[46]

Gallery of Breads

Ruisreikäleipä, a flat rye flour loaf with a hole

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 bread Etymology online. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ Igor M. Diakonoff, The Paths of History (Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0521643986).

- ↑ Prehistoric man ate flatbread 30,000 years ago Phys.org (October 19 2010). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ John Dodson, Richard Fullagar, Judith Furby, Robert Jones, and Ian Prosser, Humans and megafauna in a late Pleistocene environment from Cuddie Springs, north western New South Wales Archaeology in Oceania 28(2) (July 1993): 94-99. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Helen Briggs, Prehistoric bake-off: Scientists discover oldest evidence of bread BBC News (July 17, 2018). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Amaia Arranz-Otaegui, Lara Gonzalez Carretero, Monica N. Ramsey, Dorian Q. Fuller, and Tobias Richter, Archaeobotanical evidence reveals the origins of bread 14,400 years ago in northeastern Jordan PNAS (July 11, 2018). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Harold McGee, On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen (Scribner, 2004, ISBN 978-0684800011).

- ↑ Victor R. Preedy and Ronald Ross Watson (eds.), Flour and Breads and their Fortification in Health and Disease Prevention (Academic Press, 2019, ISBN 978-0128146392).

- ↑ Reay Tannahill, Food in History (Crown, 1995, ISBN 978-0517884041).

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History (Loeb Classics, 1938). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Jennifer Latson, How Sliced Bread Became the 'Greatest Thing' TIME (July 7, 2015). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Don Vorhees, Why Do Donuts Have Holes? Fascinating Facts About What We Eat And Drink (Citadel, 2004, ISBN 978-0806525518).

- ↑ Derek Thompson, Happy Birthday, Sliced Bread! The 'Greatest Thing' Turns 85 This Week The Atlantic (July 9, 2013). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ William S. Hammack, Sliced Bread Engineer Guy (September 16, 2003). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Alan Shaw, On this day in 1928, the first sliced bread was sold The Sunday Post (July 7, 2017). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Chorleywood: The bread that changed Britain BBC (June 7, 2011). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Dom Gregory Dix, The Shape of the Liturgy (Continuum International, 2005, ISBN 978-0826479426).

- ↑ Lady Sabrina, Exploring Wicca (Weiser, 2006, ISBN 978-1564148841).

- ↑ Juvenal, John Godwin (trans.), Juvenal Satires: Book IV (Liverpool University Press, 2016, ISBN 1910572330).

- ↑ Center For Communist Studies, Peace, Land, and Bread (Iskra Books, 2020, ISBN 1087895650).

- ↑ Tim Hayward, Loaf Story: A love-letter to bread, with recipes (Quadrille Publishing, 2020, ISBN 978-1787134775).

- ↑ K.V. Patel, The Foundation Pillars for Change: Our Nation, Our Democracy & Our Future (Partridge India, 2014, ISBN 978-1482815634).

- ↑ The best thing since sliced bread National Museum of American History, December 17, 2009. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ↑ break bread with someone The Free Dictionary. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ↑ lord Etymology Online. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ↑ Heath Goldman, Ever Wondered What Makes Bread Rise? Food Network Kitchen. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ R.J. Peña, Wheat for bread and other foods Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Wheat Grains & Legumes Nutrition Council. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Stanley Cauvain, Technology of Breadmaking (Springer, 2015, ISBN 978-3319146867).

- ↑ Shabir Ahmad Mir, Manzoor Ahmad Shah, and Afshan Mumtaz Hamdani (eds.), Gluten-free Bread Technology (Springer, 2021, ISBN 978-3030738976).

- ↑ Louis P. De Gouy, The Bread Book (Dover Publications, 2021, ISBN 978-0486847849).

- ↑ R. Dixon Phillips and John W. Finley, Protein Quality and the Effects of Processing (CRC Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0824779849).

- ↑ Jeffrey Hamelman, Bread: A Baker's Book of Techniques and Recipes (Wiley, 2004, ISBN 978-0471168577).

- ↑ Amanda Fiegl, Ratio-based Bread Baking Smithsonian Magazine (May 19, 2009). Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ↑ Why are liquid ingredients important in the bread making process? Bread Experience. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ↑ Nancy Silverton, Nancy Silverton's Breads from the La Brea Bakery (Villard, 1996, ISBN 978-0679409076).

- ↑ Peter Reinhart, The Bread Baker's Apprentice: Mastering the Art of Extraordinary Bread (Ten Speed Press, 2016, ISBN 978-1607748656).

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 Christopher Flatt, Beginners Bread Baking At Home Bread at Home. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ↑ Artisan bread baking tips: Poolish & biga Weekend Bakery. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ↑ William P. Edwards, The Science of Bakery Products (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2007, ISBN 978-0854044863).

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Alan Davidson, The Oxford Companion to Food (Oxford University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0199677337).

- ↑ Gary Hunter and Terry Tinton, Professional Chef Level 2 Diploma (Cengage Learning, 2011, ISBN 978-1408039090).

- ↑ Malia Frey, Bread Nutrition Facts and Health Benefits Verywell Fit, June 15, 2022. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ↑ Sarah Winkler, Is eating bread crust really good for you? How Stuff Works. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ↑ What is a Sandwich? The British Sandwich & Food to Go Association. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ↑ Our 10 best bread recipes The Guardian (September 6, 2014). Retrieved November 19, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cauvain, Stanley. Technology of Breadmaking. Springer, 2015. ISBN 978-3319146867

- Center For Communist Studies. Peace, Land, and Bread. Iskra Books, 2020. ISBN 1087895650

- Davidson, Alan. The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0199677337

- De Gouy, Louis P. The Bread Book. Dover Publications, 2021. ISBN 978-0486847849

- Diakonoff, Igor M. The Paths of History. Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0521643986

- Dix, Dom Gregory. The Shape of the Liturgy. Continuum International, 2005. ISBN 978-0826479426

- Edwards, William P. The Science of Bakery Products. Royal Society of Chemistry, 2007. ISBN 978-0854044863

- Hayward, Tim. Loaf Story: A love-letter to bread, with recipes. Quadrille Publishing, 2020. ISBN 978-1787134775

- Hunter, Gary, and Terry Tinton. Professional Chef Level 2 Diploma. Cengage Learning, 2011. ISBN 978-1408039090

- Juvenal, John Godwin (trans.). Juvenal Satires: Book IV. Liverpool University Press, 2016. ISBN 1910572330

- McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. Scribner, 2004. ISBN 978-0684800011

- Mir, Shabir Ahmad, Manzoor Ahmad Shah, and Afshan Mumtaz Hamdani (eds.). Gluten-free Bread Technology. Springer, 2021. ISBN 978-3030738976

- Patel, K.V. The Foundation Pillars for Change: Our Nation, Our Democracy & Our Future. Partridge India, 2014. ISBN 978-1482815634

- Phillips, R. Dixon, and John W. Finley. Protein Quality and the Effects of Processing. CRC Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0824779849

- Preedy, Victor R., and Ronald Ross Watson (eds.). Flour and Breads and their Fortification in Health and Disease Prevention. Academic Press, 2019. ISBN 978-0128146392

- Reinhart, Peter. The Bread Baker's Apprentice: Mastering the Art of Extraordinary Bread. Ten Speed Press, 2016. ISBN 978-1607748656

- Sabrina, Lady. Exploring Wicca. Weiser, 2006. ISBN 978-1564148841

- Silverton, Nancy. Nancy Silverton's Breads from the La Brea Bakery. Villard, 1996. ISBN 978-0679409076

- Tannahill, Reay. Food in History. Crown, 1995. ISBN 978-0517884041

- Vorhees, Don. Why Do Donuts Have Holes? Fascinating Facts About What We Eat And Drink. Citadel, 2004. ISBN 978-0806525518

External links

All links retrieved November 20, 2023.

- Who Invented Bread? Live Science

- Who Invented Sliced Bread? History.com

- History of Bread Making History of Bread

- A Baker’s Dozen Facts about Bread Federation of Bakers

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.