Scotland

| Scotland (English/Scots) Alba (Scottish Gaelic) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: In My Defens God Me Defend (Scots) (often shown abbreviated as In Defens) |

||||||

| Anthem: None (de jure) Various de facto1 |

||||||

| Capital | Edinburgh | |||||

| Largest city | Glasgow | |||||

| Official language(s) | English | |||||

| Recognised regional languages | Gaelic, Scots2 | |||||

| Ethnic groups (2011) | 96.0% White, 2.7% Asian, 0.7% Black, 0.4% Mixed, 0.2% Arab, 0.1% other[1] | |||||

| Demonym | Scots, Scottish3 | |||||

| Government | Devolved government within a constitutional monarchy4 | |||||

| - | Monarch | Charles III | ||||

| - | First Minister | Humza Yousaf | ||||

| - | Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | Rishi Sunak | ||||

| Legislature | Scottish Parliament | |||||

| Establishment | Early Middle Ages; exact date of establishment unclear or disputed; traditional 843, by King Kenneth MacAlpin[2] | |||||

| - | Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton | March 17, 1328 | ||||

| - | Treaty of Berwick | October 3, 1357[3] | ||||

| - | Union with England | May 1, 1707 | ||||

| - | Devolution | November 19, 1998 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 77,933 km2 30,090 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 3.00% | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2021 estimate | |||||

| - | 2011 census | 5,295,403[5] | ||||

| - | Density | 67.5/km2 174.1/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | £145.245 billion [6] | ||||

| - | Per capita | £26,572 | ||||

| Currency | Pound sterling (GBP) |

|||||

| Time zone | GMT (UTC0) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | BST (UTC+1) | ||||

| Date formats | dd/mm/yyyy (AD or CE) | |||||

| Drives on the | left | |||||

| Internet TLD | .uk5 | |||||

| Calling code | 44 | |||||

| Patron saint | St Andrew[7] St Margaret St Columba |

|||||

| 1 | Flower of Scotland, Scotland the Brave and Scots Wha Hae have been used in lieu of an official anthem. | |||||

| 2 | Both Scots and Scottish Gaelic are officially recognized as autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages; the Bòrd na Gàidhlig is tasked, under the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005, with securing Gaelic as an official language of Scotland, commanding "equal respect" with English.[8] | |||||

| 3 | Historically, the use of "Scotch" as an adjective comparable to "Scottish" or "Scots" was commonplace, particularly outwith Scotland. However, the modern use of the term describes only products of Scotland, usually food or drink related. | |||||

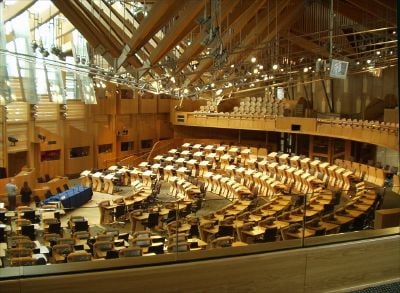

| 4 | Scotland's head of state is the monarch of the United Kingdom, currently King Charles III (since 2022). Scotland has limited self-government within the United Kingdom as well as representation in the UK Parliament. It is also a UK electoral region for the European Parliament. Certain executive and legislative powers have been devolved to, respectively, the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament at Holyrood in Edinburgh. | |||||

| 5 | Also .eu, as part of the European Union. ISO 3166-1 is GB, but .gb is unused. | |||||

Scotland (Scottish Gaelic Alba) is a nation in northwest Europe and one of the constituent countries of the United Kingdom. Scotland is not, however, a sovereign state and does not enjoy direct membership of either the United Nations or the European Union. It occupies the northern third of the island of Great Britain and shares a land border to the south with England. It is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the Irish Sea to the southwest. Apart from the mainland, Scotland consists of over 790 islands. Scottish waters contain the largest oil reserves in the European Union.

The Kingdom of Scotland was an independent state until May 1, 1707, when the Acts of Union resulted in a political union with the Kingdom of England (now England and Wales) to create the kingdom of Great Britain. Scots law, the Scottish education system, the Church of Scotland, and Scottish banknotes have been four cornerstones contributing to the continuation of Scottish culture and Scottish national identity since the Union. Devolution in 1998 brought partial independence from England. Scotland continues the struggle to enjoy true relationships not only with England but also with an increasingly globalized world community.

Etymology

The word Scot was borrowed from Latin and its use, to refer to Scotland, dates from at least the first half of the tenth century, when it first appeared in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as a reference to the Land of the Gaels, analogous to the Latin Scotia.

History

The history of Scotland began in prehistoric times, when modern humans first began to inhabit the land after the end of the last ice age. Many artifacts remain from the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age civilizations that existed there. The written history of Scotland began with the arrival of the Romans, who occupied England and Wales, leaving most of modern Scotland as unconquered Caledonia. Scotland was united under Kenneth MacAlpin in 843, and continued as a kingdom throughout the Middle Ages. The Union of the Crowns in 1707 finalized the transition to the United Kingdom, and the existence of modern Scotland.

Early Scotland

It is believed that the first hunter-gatherers arrived in Scotland around eleven thousand years ago, as the ice sheet retreated after the ice age. Groups of settlers began building the first permanent houses on Scottish soil around 9,500 years ago, and the first villages around six thousand years ago. A site from this period is the well-preserved village of Skara Brae on the Mainland of Orkney. Neolithic habitation, burial, and ritual sites are particularly common and well-preserved in the Northern and Western Isles, where a lack of trees led to most structures being constructed of local stone.

Callanish, on the West Side of the Isle of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides, is the location of a cross-shaped setting of standing stones, one of the most spectacular megalithic monuments in Scotland, dating back to around 3,000 B.C.E.

The written history of Scotland dates from the arrival of the Roman Empire in southern and central Great Britain, when the Romans occupied what is now England and Wales, administering it as a Roman province called Britannia. To the north was Caledonia, territory not conquered by the Romans. The name represents that of a Pictish tribe, the Caledonii, one amongst several in the region, but perhaps the dominant tribe. The Roman Emperor Hadrian, realizing that the Caledonians would refuse to cohabitate with the Romans, and that the harsh terrain and highlands made its conquest costly and unprofitable for the Empire at large, decided instead to build a wall. Ruins of parts of this wall, bearing his name, still stand.

Pictland became dominated by the Pictish sub-kingdom of Fortriu. The Gaels of Dál Riata peopled Argyll. From this people came Cináed mac Ailpín (anglicized Kenneth MacAlpin), who united the kingdom of Scotland in 843, when he became King of the Picts and Gaels.

Medieval Scotland

In the following centuries, the kingdom of Scotland expanded to something closer to modern Scotland. The period was marked by comparatively good relations with the Wessex rulers of England, intense internal dynastic disunity, and relatively successful expansionary policies. Sometime after an invasion of the kingdom of Strathclyde by King Edmund of England in 945, the province was handed over to King Malcolm I. During the reign of King Indulf (954–962), the Scots captured the fortress later called Edinburgh, their first foothold in Lothian. The reign of Malcolm II saw fuller incorporation of these territories. The critical year was 1018, when Malcolm II defeated the Northumbrians at the Battle of Carham.

The Norman Conquest of England in 1066 initiated a chain of events which started to move the kingdom of Scotland away from its originally Gaelic cultural orientation. Malcolm III married Margaret, the sister of Edgar Ætheling, the deposed Anglo-Saxon claimant to the throne of England. Margaret played a major role in reducing the influence of Celtic Christianity. Her influence, which stemmed from a lifelong dedication to personal piety, was essential to the revivification of Roman Catholicism in Scotland, a fact that led to her canonization in 1250.

When Margaret's youngest son David I later succeeded, having previously become an important Anglo-Norman lord through marriage, David I introduced feudalism into Scotland, and encouraged an influx of settlers from the "low countries" to the newly-founded burghs to enhance trading links with mainland Europe and Scandinavia. By the late thirteenth century, scores of Norman and Anglo-Norman families had been granted Scottish lands. The first meetings of the Parliament of Scotland were convened during this period.

The death of Alexander III in March 1286, followed by the death of his granddaughter Margaret, Maid of Norway, the last direct heir of Alexander III of Scotland, in 1290, broke the centuries old succession line of Scotland's kings. This led to the requested arbitration of Edward I, King of England, to adjudicate between rival claimants to the vacant Scottish throne, a process known as the Great Cause. John Balliol was chosen as king, having the strongest claim in feudal law, and was inaugurated at Scone, on November 30, 1292, St. Andrew's Day. In 1294 Balliol and other Scottish lords refused Edward's demands to serve in his army against the French. Instead the Scottish parliament sent envoys to France to negotiate an alliance. Scotland and France signed a treaty on October 23, 1295 that came to be known as the Auld Alliance (1295–1560). War ensued and King John was deposed by Edward who took personal control of Scotland.

The Scots resisted in what became known as the Wars of Scottish Independence (1296–1328). Sir William Wallace and Andrew de Moray emerged as the principal leaders in support of John Balliol, and later Robert the Bruce. Bruce, crowned as King Robert I on March 25, 1306, won a decisive victory over the English at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. Warfare flared up again after his death during the Second War of Scottish Independence from 1332 to 1357, in which Edward Balliol unsuccessfully attempted to win back the throne from Bruce's heirs, with the support of the English king. Eventually, with the emergence of the Stewart dynasty in the 1370s, the situation in Scotland began to stabilize.

In 1542, James V died leaving only his infant child Mary as heir to the throne. She was crowned when only nine months old, becoming Mary, Queen of Scots, and a regent ruled while Mary grew up. This was the time of John Knox and the Scottish Reformation. Intermittent wars with England, political unrest, and religious change dominated the late sixteenth century, and Mary was finally forced to abdicate the Scottish throne in favor of her son James VI.

Modern Scotland

In 1603, when Elizabeth I died, James VI of Scotland inherited the throne of the Kingdom of England, becoming also James I of England. With the exception of a short period under The Protectorate, Scotland remained a separate state, but there was considerable conflict between the crown and the Covenanters over the form of church government. After the Glorious Revolution and the overthrow of the Roman Catholic James VII by William and Mary, Scotland briefly threatened to select a separate Protestant monarch. In 1707, however, following English threats to end trade and free movement across the border, the Scots Parliament and the Parliament of England enacted the twin Acts of Union, which created the Kingdom of Great Britain.

Two major Jacobite risings launched from the Highlands of Scotland in 1715 and 1745 failed to remove the House of Hanover from the British throne.

Because of the geographical orientation of Scotland, and its strong reliance on trade routes by sea, the nation held close links in the south and east with the Baltic countries, and through Ireland with France and the continent of Europe. Following the Scottish Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, Scotland became one of the commercial, intellectual, and industrial powerhouses of Europe, producing philosophers such as Adam Smith and David Hume, and inventors and entrepreneurs such as Alexander Graham Bell, James Watt, and Andrew Carnegie.

After World War II, Scotland experienced an industrial decline which was particularly acute. Only in the latter part of the twentieth century did the country enjoy something of a cultural and economic renaissance. Factors contributing to this recovery included a resurgent financial services and electronics sector, the proceeds of North Sea oil and gas, and the devolved Scottish Parliament, established by the UK government under the Scotland Act 1998.

Politics

As one of the constituent countries of the United Kingdom, the head of state in Scotland is the British monarch, King Charles III.

Political debate in Scotland in the latter half of the twentieth century revolved around the constitution, and this dominated the Scottish political scene. Following the symbolic restoration of national sovereignty with the return of the Stone of Scone to Edinburgh from London, and after devolution (or Home Rule) occurred, debate continued over whether the Scottish Parliament should accrue additional powers (for example over fiscal policy), or seek to obtain full independence with full sovereign powers (either through independence, a federal United Kingdom, or a confederal arrangement).

Under devolution, executive and legislative powers in certain areas have been constitutionally delegated to the Scottish Executive and the Scottish Parliament at Holyrood in Edinburgh respectively. The United Kingdom Parliament at Westminster in London retains active power over Scotland's taxes, social security system, the military, international relations, broadcasting, and some other areas explicitly specified in the Scotland Act 1998. The Scottish Parliament has legislative authority for all other areas relating to Scotland, and has limited power to vary income tax.

The programs of legislation enacted by the Scottish Parliament have seen a divergence in the provision of social services compared to the rest of the United Kingdom. For instance, the costs of a university education and care services for the elderly are free at point of use in Scotland, while fees are paid in the rest of the UK. Scotland was the first country in the UK to ban smoking in public places.[9]

Law

Scots law is the legal system of Scotland and has a basis in Roman law, combining features of both uncodified civil law dating back to the Corpus Juris Civilis and common law with medieval sources. The terms of the Treaty of Union with England in 1707 guaranteed the continued existence of a separate legal system in Scotland from that of England and Wales, and because of this it constitutes a discrete jurisdiction in international law.[10]

Scots law provides for three types of courts: civil, criminal, and heraldic. The supreme civil court is the Court of Session, although civil appeals can be taken to the House of Lords in London, and the High Court of Justiciary is the supreme criminal court. Both courts are housed at Parliament House in Edinburgh. The sheriff court is the main criminal and civil court, with 39 sheriff courts throughout the country.[11] District courts were introduced in 1975 for minor offenses. The Court of the Lord Lyon regulates heraldry.

Scots law is unique in that it allows three verdicts in criminal cases, including the controversial "not proven" verdict which is used when the jury does not believe the case has been proven against the defendant but is not sufficiently convinced of their innocence to bring in a not guilty verdict. In 2022, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon announced her intention to introduce a Criminal Justice Bill that would include the abolition of the not proven verdict.[12]

Geography

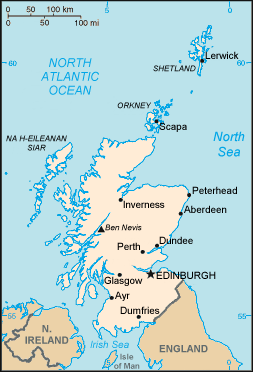

Scotland comprises the northern third of the island of Great Britain, off the coast of northwestern Europe. Scotland's only land border is with England, running for 60 miles between the River Tweed on the east coast and the Solway Firth in the west.

The country consists of a mainland area plus several island groups. The mainland has three areas: the Highlands in the north; the Central Belt, and the Southern Uplands in the south. The Highlands are generally mountainous and are bisected by the Great Glen, which includes Loch Ness. The highest mountains in the British Isles are found there, including Ben Nevis, the highest peak at 4,409 feet. The Central Belt is generally flat and is where most of the population resides. This area is divided into the West Coast, which contains the areas around Glasgow; and the East Coast which includes the areas around the capital, Edinburgh.

Scotland has over 790 islands divided into four main groups: Shetland, Orkney, and the Hebrides, divided into the Inner Hebrides and Outer Hebrides. St. Kilda is the most remote of all the inhabitable Scottish islands, being over one hundred miles from the mainland. Almost all the islands surrounding Scotland, no matter how small or remote, were formerly inhabited, as is shown by archaeological and documentary evidence. In general only the more accessible and larger islands retain human populations (though these are in some cases very small). Access to several islands in the Northern and Western groups was made easier in the course of the twentieth century by the construction of bridges or causeways installed for strategic reasons during the Second World War.

Climate

The climate of Scotland is temperate and oceanic, and tends to be very changeable. It is warmed by the Gulf Stream from the Atlantic, and as such is much warmer than areas on similar latitudes, for example Oslo, Norway. However, temperatures are generally lower than in the rest of the UK, with the coldest ever UK temperature of −27.2 °C (−16.96 °F) recorded at Braemar in the Grampian Mountains, on February 11, 1895 and January 10, 1982, and at Altnaharra, Highland, on December 30, 1995.[13] Winter maximums average 6 °C (42.8 °F) in the lowlands, with summer maximums averaging 18 °C (64.4 °F). The highest temperature recorded was 34.8 °C (94.6 °F) at Charterhall, Scottish Borders on July 19, 2022.[14] In general, the west of Scotland is warmer than the east, due to the influence of the Atlantic ocean currents, and the colder surface temperatures of the North Sea. Tiree, in the Inner Hebrides, is one of the sunniest places in the country: it had more than 300 hours of sunshine in May of 1975.[14]

Rainfall varies widely across Scotland. The western highlands of Scotland are the wettest, with annual rainfall exceeding 3,500 millimeters (140 in).[15] In comparison, much of lowland Scotland receives less than 700 mm (27.6 in) annually.[16] Heavy snowfall is not common in the lowlands, but becomes more common with altitude. The number of days with snow falling averages about 20 per winter along the coast but over 80 days over the Grampians, while many coastal areas average fewer than 10 days.[16]

Economy

The Scottish economy is closely linked with that of the rest of Europe and the wider Western world, with a heavy emphasis on exporting. It is essentially a market economy with some government intervention. After the Industrial Revolution, the Scottish economy concentrated on heavy industry, dominated by the shipbuilding, coal mining, and steel industries. Scotland was an integral component of the British Empire which allowed the Scottish economy to export its output throughout the world.

Heavy industry declined, however, in the latter part of the twentieth century, leading to a shift in the economy of Scotland towards a technology and service sector-based economy. The 1980s saw an economic boom in the "Silicon Glen" corridor between Glasgow and Edinburgh, with many large technology firms relocating to Scotland. The discovery of North Sea oil in the 1970s also helped to transform the Scottish economy, as Scottish waters make up a large sector of the North Atlantic and the North Sea, which contain the largest oil reserves in the European Union.[17]

The largest export products for Scotland are niche products such as whisky, electronics, and financial services. Edinburgh is the financial services center of Scotland and the sixth largest financial center in Europe, with many large finance firms based there, including the Royal Bank of Scotland.[18]

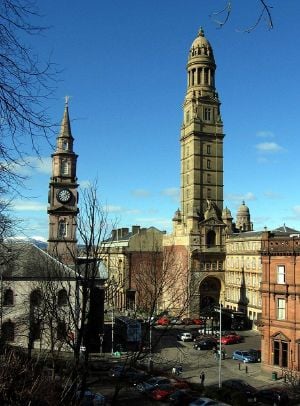

Glasgow is Scotland's leading seaport and is the fourth largest manufacturing center in the UK, accounting for well over sixty percent of Scotland's manufactured exports. Shipbuilding, although significantly diminished from its heights in the early twentieth century, still forms a large part of the city's manufacturing base.

Aberdeen is the center of the North Sea oil industry. Other important industries include textile production, chemical work, distilling, brewing, commercial fishing and tourism.

Only about one-quarter of the land is under cultivation (principally in cereals and vegetables), but sheep farming is important in the less arable highland and island regions. Most land is concentrated in relatively few hands; some 350 people own about half the land. As a result, in 2003 the Scottish Parliament passed a Land Reform Act that empowered tenant farmers and local communities to purchase land even if the landlord did not want to sell.

Although the Bank of England is the central bank for the UK, three Scottish clearing banks still issue their own Sterling banknotes: the Bank of Scotland; the Royal Bank of Scotland; and the Clydesdale Bank. These notes have no status as legal tender in England, Wales, or Northern Ireland, although they are fungible with the Bank of England banknotes.

Military

Although Scotland has a long military tradition that predates the Act of Union with England, its armed forces now form part of the British Armed Forces.

Due to their topography and perceived remoteness, parts of Scotland have housed many sensitive defense establishments, with mixed public feelings. The proportionally large amount of military bases in Scotland, when compared to other parts of the UK, has led some to use the euphemism "Fortress Scotland."[19]

Demographics

The population of Scotland is somewhat over 5 million. The highest concentration of population is in the areas surrounding Glasgow, with over 2 million people living in west central Scotland centered on the Greater Glasgow urban conurbation.

Although the Highlands were widely populated in the past, the "Highland Clearances" (a series of forcible evictions), followed by continuing emigration since the eighteenth century, greatly reduced numbers living there. Those that remain live in crofting townships—irregular groupings of subsistence farms of a few acres each.

Scotland has the highest proportion of redheads of any country worldwide, with around thirteen percent of the population having naturally red hair. A further forty percent of Scots carry the gene which results in red hair.

Due to immigration since World War II, Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Dundee have significant Asian and Indian populations.

Languages

Since the United Kingdom lacks a codified constitution, there is no official language. However, Scotland has three officially recognized languages: English, Scottish Gaelic, and Scots. De facto English is the main language, and almost all Scots speak Scottish Standard English.

During the twentieth century the number of native speakers of Gaelic, a Celtic language similar to Irish, declined from around five percent to just one percent of the population, almost always on a fully bilingual basis with English.[20] Gaelic is mostly spoken in the Western Isles, where the local council uses the Gaelic name—Comhairle nan Eilean Siar "(Council of the Western Isles)." Under the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005, which was passed by the Scottish Parliament to provide a statutory basis for a limited range of Gaelic language service provision, English and Gaelic receive "equal respect" but do not have equal legal status.[21]

Scots and Gaelic were recognized under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages ratified by the UK in 2001, and the Scottish Executive is committed, based on the UK's undertakings, to providing support for both. The General Register Office for Scotland estimates that thirty percent of the population are fluent in Scots, a West Germanic sister language to English.

Religion

The Church of Scotland, also known as The Kirk, is the national church and has a Presbyterian system of church government. It is not subject to state control nor is it "established" as is the Church of England within England. It was formally recognized as independent of the UK Parliament by the Church of Scotland Act 1921, settling centuries of dispute between church and state over jurisdiction in spiritual matters.

Early Pictish religion in Scotland is presumed to have resembled Celtic polytheism (Druidism). Remnants of this original spirituality persist in the Highlands through the phenomenon of "second sight," and more recently established spiritual communities such as Findhorn.[22]

Christianity came to Scotland around the second century, and was firmly established by the sixth and seventh centuries. However, the Scottish "Celtic" Church had marked liturgical and ecclesiological differences from the rest of Western Christendom. Some of these were resolved at the end of the seventh century following Saint Columba's withdrawal to Iona, however, it was not until the eleventh century that the Scottish Church became an integral part of the Roman communion.

The Scottish Reformation, initiated in 1560 and led by John Knox, was Calvinist, and throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Church of Scotland maintained this theology and kept a tight control over the morality of much of the population. The Church had a significant influence on the cultural development of Scotland in early modern times, famously exemplified in Eric Liddell's refusal to race at the Olympic Games on Sunday—the Sabbath.

Other Protestant denominations in Scotland include the Free Church of Scotland, an off-shoot from the Church of Scotland adhering to a more conservative style of Calvinism, the Scottish Episcopal Church, which forms part of the Anglican Communion, the Methodists, the Congregationalists, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Roman Catholicism in Scotland survived the Reformation, especially on islands such as Uist and Barra, despite the suppression of the sixteenth to the late eighteenth centuries. Roman Catholicism was strengthened in the west of Scotland during the nineteenth century by immigration from Ireland. This continued for much of the twentieth century, during which significant numbers of Catholics from Italy and Poland also migrated to Scotland. Much of Scotland (particularly the West Central Belt around Glasgow) has experienced problems caused by sectarianism, particularly football rivalry between the traditionally Roman Catholic team, Celtic, and the traditionally Protestant team, Rangers.

Islam is the largest non-Christian religion in Scotland; there are also significant Jewish and Sikh communities, especially in Glasgow. Scotland also has a relatively high proportion of persons who regard themselves as belonging to "no religion."

Education

The education system in Scotland is distinct from the rest of the United Kingdom. The early roots were in the Education Act of 1496, which first introduced compulsory education for the eldest sons of nobles. Then, in 1561, the principle of general public education was set with the establishment of the national Kirk, which set out a national program for spiritual reform, including a school in every parish. Education finally came under the control of the state rather than the Church, and became compulsory for all children with the implementation of the Education Act of 1872. As a result, for over two hundred years Scotland had a higher percentage of its population educated at primary, secondary, and tertiary levels than any other country in Europe. The differences in education have manifested themselves in different ways, but most noticeably in the number of Scots who went on to become leaders in their fields and at the forefront of innovation and discovery, leading to many Scottish inventions during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Children in Scotland sit Standard Grade exams at the age of 15 or 16, sometimes earlier, for up to eight subjects including compulsory exams in English, mathematics, a foreign language, a science subject, and a social subject. The school leaving age is 16, after which students may choose to remain at school and study for Higher Grade and other advanced exams. A small number of students at certain private, independent schools may follow the English system take English GCSE and other exams.

Scotland has 13 universities, including the four ancient universities of Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and St. Andrews founded during the medieval period. Bachelor's degrees at Scottish universities are bestowed after four years of study, with an option to graduate with an "ordinary degree" after only three years of study, instead of an "honors degree." Unlike the rest of the United Kingdom, Scottish students studying at a Scottish university do not have to pay tuition fees. All Scottish universities attract a high percentage of overseas students, and many have links with overseas institutions.

Culture

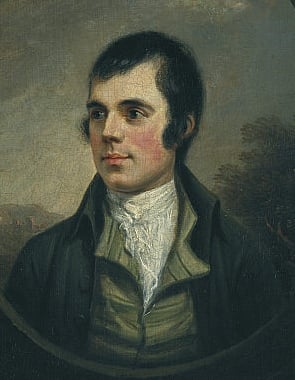

Scots have a reputation for thriftiness, hard work, and pride in their traditions. Scots worldwide celebrate a "Burns Supper" on the birthday of national poet Robert Burns, with a bagpipe player leading the entrance of the traditional meal of haggis. The culture of Scotland is distinct and internationally recognized. However, the heavy influence by that of neighboring England to the extent that Scots have felt inferior, led to the phenomenon of "Scottish cringe."[23]

Scotland has its own unique arts scene with both music and literature. The annual Edinburgh International Festival, including its "Fringe" entertainment, is a major cultural event. There are also several Scottish sporting traditions that are unique to the British Isles. The Loch Ness Monster, familiarly known as "Nessie," a mysterious and unidentified legendary creature claimed to inhabit Scotland's Loch Ness, is well known throughout the United Kingdom and the world.

Music

The Scottish music scene is a significant aspect of Scottish culture, with both traditional and modern influences. A traditional Scottish instrument is the Great Highland Bagpipe, a wind instrument consisting of musical pipes which are fed continuously by a reservoir of air in a bag. The Clàrsach (a form of harp), fiddle, and accordion are also traditional Scottish instruments, the latter two heavily featured in Scottish country dance bands.

Literature

Scottish literature has included writings in English, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, Brythonic, French, and Latin. Some of the earliest literature known to have been composed in Scotland dates from the sixth century and includes The Gododdin written in Brythonic (Old Welsh) and the Elegy for St Columba by Dallan Forgaill written in Middle Irish. Vita Columbae by Adomnán, the ninth Abbot of Iona, was written in Latin during the seventh century. In the thirteenth century, French flourished as a literary language long before early Scots texts appeared in the fourteenth century. After the seventeenth century, Anglicization increased. The poet and songwriter Robert Burns wrote in the Scots language, although much of his writing is also in English and in a "light" Scots dialect, which would have been accessible to a wider audience.

The introduction of the movement known as the "kailyard tradition" at the end of the nineteenth century brought elements of fantasy and folklore into fashion. J. M. Barrie provides a good example of this mix of modernity and nostalgia. However, this tradition has been viewed as a major stumbling block for Scottish literature, focusing on an idealized, pastoral picture of Scottish culture, becoming increasingly removed from the reality of life in Scotland. Novelists such as Irvine Welsh, (of Trainspotting fame), by contrast, have written in a distinctly Scottish English, reflecting the underbelly of contemporary Scottish culture.

Sport

Scotland has its own national governing bodies, such as the Scottish Football Association (the second oldest national football association in the world) and the Scottish Rugby Union, and its own national sporting competitions. As such, Scotland enjoys independent representation at many international sporting events such as the FIFA World Cup, the Rugby World Cup and the Commonwealth Games, although notably not the Olympic Games.

Scotland is the "Home of Golf," and is well-known for its many golf courses, including the Old Course at St. Andrews. Other distinctive features of the national sporting culture include the Highland Games, curling, and shinty.

Transport

Scotland has four main international airports (Glasgow, Edinburgh, Prestwick, and Aberdeen) that serve a wide variety of European and intercontinental routes. Highland and Islands Airports operate ten regional airports serving the more remote locations of Scotland.[24] There is technically no national airline, although various airlines have their base in Scotland.

Scotland has a large and expanding rail network, which, following the Railways Act of 2005, is managed independently from the rest of the UK.[25] The Scottish Executive has pursued a policy of building new railway lines, and reopening closed ones.

Regular ferry services operate between the Scottish mainland and island communities. International ferry travel is available from Rosyth (near Edinburgh) to Zeebrugge in Belgium, and from Lerwick (Shetland Islands) to Bergen, Norway, and also to the Faroe Islands and on to Iceland.

National symbols

- The Flag of Scotland, the Saltire or St. Andrew's Cross, dates (at least in legend) from the ninth century, and is thus the oldest national flag still in use.

- The Royal Standard of Scotland, a banner showing the Royal Arms of Scotland, is also frequently to be seen, particularly at sporting events involving a Scottish team. Often called the "Lion Rampant" (after its chief heraldic device), it is technically the property of the monarch.

- The unicorn is also used as a heraldic symbol of Scotland. The Royal Coat of Arms of Scotland, used prior to 1603 by the Kings of Scotland, incorporated a lion rampant shield supported by two unicorns.

- The thistle, the floral emblem of Scotland, is featured in many Scottish symbols and logos, and on UK currency. Heather is also considered to be a symbol of Scotland.

- Tartan is a specific woven textile pattern that often signifies a particular Scottish clan, as featured in a kilt.

Gallery of images

Notes

- ↑ Ethnic groups, Scotland, 2001 and 2011 Scotland Census. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Dauvit Brown "Kenneth mac Alpin" in M. Lynch (ed.) The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0192116963), 359.

- ↑ The Treaty of Berwick was signed - On this day in Scottish history History Scotland. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Scotland population mid-year estimate Office for National Statistics. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ↑ Population Scotland's Census. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Trevor Fenton, Regional gross value added (balanced) per head and income components Office for National Statistics. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ St Andrew, Patron Saint of Scotland Historic UK. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Scotland begins pub smoking ban BBC News, March 26, 2006. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ J. G. Collier, Conflict of Laws (Cambridge University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0521787819).

- ↑ Sheriff Courts National Records of Scotland. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Alistair Grant, Scotland's controversial 'not proven' verdict set to be abolished The Scotsman, September 6, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Met Office, Top ten coldest recorded temperatures in the UK Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Met Office, UK climate extremes Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Western Scotland: Climate Met Office. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Eastern Scotland: Climate Met Office. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Map Referred to in the Scottish Adjacent Waters Boundaries Order 1999 Government of the United Kingdom,. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Mark Milner and Jill Treanor, Devolution may broaden financial sector's view The Guardian, July 1, 1999. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Malcolm Spaven, Fortress Scotland (London: Pluto Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0861047352).

- ↑ Kenneth MacKinnon, A Century on the Census—Gaelic in Twentieth Century Focus Second International Conference on the Languages of Scotland, University of Glasgow, (June 30 to July 2, 1988). Retrieved July 30, 2023

- ↑ MSPs Rule Against Gaelic Equality BBC News, April 21, 2005. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Findhorn Foundation Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ I want to end the Scottish cringe BBC News, February 28, 2004. July 30, 2023.

- ↑ Highlands and Islands Airports Limited Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ↑ About ScotRail ScotRail. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burleigh, J.H.S. A Church History of Scotland. Oxford University Press, 1960. ISBN 0192139215

- Collier, J.G. Conflict of Laws. Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0521787819

- Devine, T.M. The Scottish Nation: A History, 1700-2000. Penguin, 2001. ISBN 978-0141002347

- Lynch, M. (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0192116963

- Smout, T.C. A History of the Scottish People. Fontana Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0006860273

- Spaven, Malcolm. Fortress Scotland. London: Pluto Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0861047352

- Spottiswood, John. The History of the Church of Scotland. AMS Press, 1973. ISBN 0404528406

- Wormald, Jenny (ed.). Scotland: A History. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0198206156

External links

All links retrieved July 30, 2023.

- The Gazetteer for Scotland

- Scotland's Wildlife

- The Scottish Government

- Scottish Parliament

- Scottish National Tourist Board

- Scotlands People The official Scottish genealogy resource

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.