| Protestantism |

Waldensians (France/Germany/Italy)

Anabaptism

Puritanism

Revivalism

Restoration movement |

Protestantism encompasses forms of Christian faith and practice that originated with doctrines and religious, political, and ecclesiological impulses of the Protestant Reformation. The word Protestant is derived from the Latin protestatio, meaning declaration. It refers to the letter of protestation by Lutheran princes against the decision of the Diet of Speyer in 1529, which reaffirmed the edict of the Diet of Worms condemning the teachings of Martin Luther as heresy. The term Protestantism, however, has been used in several different senses, often as a general term to refer to Western Christianity that is not subject to papal authority, including some traditions that were not part of the original Protestant movement.

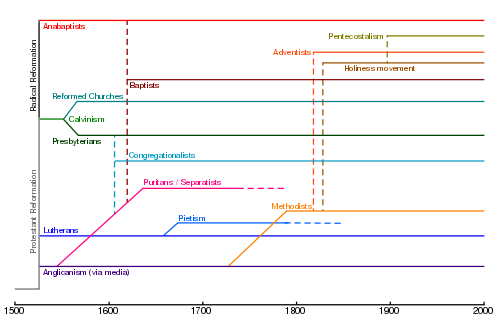

Protestants generally may be divided among four basic groups: The "mainline" churches with direct roots in the Protestant reformers, the Radical Reform movement emphasizing adult baptism, nontrinitarian churches, and the Restorationist movements of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Various denominations exist within each group, and not every denomination fits neatly into these categories.

Mainline Protestants share a rejection of the authority of the Roman pope and generally deny the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, although they disagree among themselves about the doctrine of Christ's presence in the Eucharist. They emphasize the priesthood of all believers, the doctrine of justification by faith alone, and a belief in the Bible, rather than Catholic tradition, as the legitimate source of faith. However, there is substantial disagreement among the Protestant groups about the interpretation of these principles and not all groups generally characterized as Protestant adhere to them entirely.

The number of Protestant denominations is estimated to be in the thousands, and attempts at unification through various ecumenical movements have not kept pace with the tendency of groups to divide or new ones to develop. The total number of Protestants in the world today is estimated at around 600 million.

Historical roots

The roots of Protestantism are often traced to movements in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries which protested against the wealth and exploitation of the medieval Catholic hierarchy in Europe. Among them were Waldensians, Hussites, Lollards, and other groups denounced as heretical, but whose main opposition to the institutional church centered on issues of the corruption of the clergy, the rights of the laity, and translation of the scriptures into the vernacular languages. In addition the Christian humanism of the Renaissance stimulated unprecedented academic ferment, and a concern for academic freedom in the universities, which were still basically religious institutions.

Protestants generally mark their separation from the Roman Catholic Church in the early sixteenth century. The movement erupted in several places at once, particularly in Germany beginning in 1517, when Martin Luther, a monk and professor at the University of Wittenberg, called for reopening of debate on the sale of indulgences. The advent of the printing press facilitated the rapid spread of the movement through the publication of documents such as Luther's 95 Theses and various pamphlets decrying the abuse of papal and ecclesiastical power. A parallel movement spread in Switzerland under the leadership of Huldrych Zwingli.

The first stage of the Reformation resulted in the excommunication of Luther and condemnation of the Reformation by the pope. However, the support of some of the German princes prevented the Church from crushing the revolt. The work and writings of John Calvin soon became influential, and the separation of the Church of England from Rome under Henry VIII soon brought England into the fold of the Reformation as well, although in a more conservative variety.

Although the Reformation began as a movement concerned mainly concerned with ecclesiastical reform, it soon began to take on a theological dimension as well. Beginning with Luther's challenge to the doctrine of papal authority and apostolic succession, it moved into questions of soteriology (the nature of salvation) and sacramental theology (especially regarding the Eucharist and baptism), resulting in several distinct Protestant traditions. The Luthean principle of sola scriptura soon opened the way to a wide variety of Protestant faiths based on various interpretations of biblical theology.

Major groupings

The churches most commonly associated with Protestantism can be divided along four fairly definitive lines:

- Mainline Protestants—a North American phrase—are those who trace their lineage to Luther, Calvin, or Anglicanism. They uphold the traditionaldoctrines of the Reformation outlined above and include such denominations as Lutherans, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Congregationalists, Methodists, and many Evangelicals.

- Anabaptists are a movement that developed from the Radical Reformation, which promoted the doctrine of believer's baptism. Today, this category includes denominations such as Baptists, Pentecostals, Adventists, Brethren, Mennonites, and Amish.

- Nontrinitarian movements reject the doctrine of the trinity. Today, they include such denominations as the Christian Scientists, Unitarians, Universalists, and many Quakers.

- Restorationists emphasize the concept of a direct renewal of God's church rather than a reformation of an existing tradition. They include fairly mainline faiths like the Churches of Christ and Disciples of Christ, as such more controversial denominations as the Latter-day Saints, Seventh Day Adventists, and Jehovah's Witnesses.

Denominations

Protestants often refer to specific Protestant churches and groups as denominations. The term also is used as an alternative to "sect," which has a negative connotation in some countries, similar to "cult." Some denominations are less accepting of other groups, and the basic orthodoxy of some is often questioned by others, as well as by the Catholic and Orthodox churches.

Individual denominations have formed over very subtle theological differences, while some denominations are simply regional or ethnic expressions of a larger denominational tradition. The actual number of distinct denominations is hard to calculate, but has been estimated in the thousands. Various ecumenical movements have attempted cooperation or reorganization of Protestant churches according to various models of union, but divisions continue to outpace unions.

There are an estimated 590 million Protestants worldwide. These include 170 million in North America, 160 million in Africa, 120 million in Europe, 70 million in Latin America, 60 million in Asia, and 10 million in Oceania. Nearly 27 percent of the 2.1 billion Christians in the world are Protestants.

Distinct denominational families include the following:

- Adventist

- Anabaptist

- Anglican/Episcopalian

- Baptist

- Calvinist

- Congregational

- Lutheran

- Methodist/Wesleyan

- Non-denominational

- Pentecostal

- Plymouth Brethren

- Presbyterian

- Quakerism

- Reformed

- Restoration movement

- Unitarian

Mainline Protestant theology

Mainline Protestantism emerged out of the Reformation's separation from the Catholic Church in the sixteenth century, based on a theology which came to be characterized as the Five Solas. These five Latin phrases (or slogans) summarize the Reformers' basic theological beliefs in contradistinction to the Catholic teaching of the day. The Latin word sola means "alone" or "only." The five solas were what the Reformers believed to be the only things needed for salvation. This formulation was intended to oppose what the Reformers viewed as deviations in the Catholic tradition from the essentials of Christian life and practice.

- Solus Christus: Christ alone

- Christ is the only mediator between God and man, affirmed in opposition to the Catholic dogma of the pope as Christ's representative on earth and of a "treasury" of the merits of saints.

- Sola scriptura: Scripture alone

- The Bible alone, rather than Church tradition, is the basis of sound Christian doctrine.

- Sola fide: Faith alone

- While practicing good works attests to one's faith in Christ and his teachings, faith in Christ, rather than good works, is the only means of salvation.

- Sola gratia: Grace alone

- Salvation is entirely the act of God, based on the redemptive suffering and death of Jesus Christ. Since no one deserves salvation, the believer is accepted without any regard for the merit of his works or character.

- Soli Deo gloria: Glory to God alone

- All glory is due to God, and not to human beings or the institutions they create, even in God's name.

Real presence in the Lord's Supper

The Protestant movement began to coalesce into several distinct branches in the mid-to-late sixteenth century. One of the central points of divergence was controversy over the Lord's Supper, or Eucharist.

Early Protestants generally rejected the Roman Catholic dogma of transubstantiation, which teaches that the bread and wine used in the of the Mass are literally transformed into the body and blood of Christ. However, they disagreed with one another concerning the manner in which Christ is present in Holy Communion.

- Lutherans hold to the idea of consubstantiation, which affirms the physical as well as the spirit presence of Christ's body "in, with, and under" the consecrated bread and wine, but rejects the idea that the consecrated bread and wine stop being bread and wine.

- Calvinists affirm that Christ is present to the believer with rather than in the elements of the Eucharist. Christ presents himself through faith—the Eucharist being an outward and visible aid, which is often referred to as dynamic presence of Christ, as opposed to the Lutheran real presence.

- Anglicans recognize Christ's presence in the Eucharist in a variety of ways depending on specific denominational, diocesan, and parochial emphasis—ranging from acceptance of the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, through the Lutheran position, to more Calvinistic notions.

- Many Protestants do not define the issue precisely, seeing the elements of the Lord's Supper as a symbol of the shared faith of the participants and a reminder of their standing together as the Body of Christ.

"Catholicity"

The concept of a catholic, or universal, church was not brushed aside during the Protestant Reformation. Indeed, visible unity of the universal church was an important doctrine for the Reformers. Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Ulrich Zwingli all believed that they were reforming a corrupt and heretical Catholic Church, and each of them took seriously the charges of schism and "innovation."

Wherever the Reformation succeeded in Europe, the result was a reformed national church envisioned to be a part of the whole visible "Holy Catholic Church" described in the traditional Christian creeds, but disagreeing in certain important points of doctrine and practice with what had been previously considered the norm. The reformed churches thus believed in a form of catholicity, founded on their doctrines of the five solas and a visible ecclesiastical organization based on the fourteenth and fifteenth century conciliar movement. They thus rejected the papacy and papal infallibility in favor of ecumenical councils, but rejected the Council of Trent (1545-63), which was organized under the auspices of Rome in opposition to the Reformation.

Today there is a growing movement of Protestants that reject the designation "Protestant" because of its negative "anti-Catholic" connotations, preferring the designation "Reformed," "Evangelical," or other designations.

Othe types of Protestanism

Radical Reformation

Unlike mainstream Evangelical (Lutheran), Reformed (Zwinglian and Calvinist) Protestant movements, the Radical Reformation had no state sponsorship and generally abandoned the idea of the "visible church" as distinct from the true, or invisible body or authentic believers. For them, the church might consist of a small community of believers, who were the true "elect" saints of God.

A key concept for the Radical Reformation was "believer's baptism", which implied that only those who had reached the age of reason and could affirm for themselves their faith in Christ could be baptized. By thus rejecting the practice of infant baptism, they were declared heretics by mainline Protestants and Catholics alike, and often faced brutal persecution as a result. These were the Anabaptists of Europe, some of whom came to America and formed the Mennonite and Amish denominations, as well as the Baptists of England and America.

Pietism and Methodism

The German Pietist movement, together with the influence of the Puritan Reformation in England in the seventeenth century, were important influences upon John Wesley and Methodism, as well as through smaller, new groups such as the Religious Society of Friends ("Quakers") and the Moravian Brethren from Herrnhut, Saxony, Germany.

The practice of a spiritual life, typically combined with social engagement, predominates in classical Pietism, which was a protest against the doctrine-centeredness, Protestant Orthodoxy of the times, in favor of depth of religious experience. Many of the more conservative Methodists went on to form the Holiness movement, which emphasized a rigorous experience of holiness in practical, daily life.

Evangelicalism

Beginning at the end of the eighteenth century, several international revivals of Pietism (such as the Great Awakening and the Second Great Awakening) took place across denominational lines. These formed what is generally referred to as the Evangelical movement. The chief emphases of this movement are individual conversion, personal piety and Bible study, public morality, a de-emphasis on formalism in worship and in doctrine, a broadened role for laity (including women), and cooperation in evangelism across denominational lines. Some mainline and Baptist denominations are included in this category.

In reaction to Biblical criticism and increasing liberalism in the mainline denominations, Christian Fundamentalism arose in the twentieth century, primarily in the United States and Canada among those denominations most affected by Evangelicalism. Christian Fundamentalism places primary emphasis on the authority and inerrancy of the Bible, an holds firmly to "fundamental" theological doctrines such as the Virgin Birth and Second Coming of Christ on the clouds.

Nontrinitarian movements

The most prominent nontrinitarian denominations today are the Unitarians, Christian Scientists, and Quakers. Unitarian beliefs were expressed by some of the early reformers in Europe, but their views were harshly condemned by other reformers. Unitarianism grew as a persecuted minority in such places as Poland, Transylvania, the British Isles and the United States. The American Unitarian Association was formed in Boston in 1825.

Quakerism is not an expressly anti-trinitarian doctrine, but most Quakers today are not trinitarians. Christian Science defines its teachings as a non-traditional idea of the Trinity: "God the Father-Mother, Christ the spiritual idea of sonship, and thirdly Divine Science or the Holy Comforter." Universalism accepts both trinitarian and nontrintarian beliefs, as well as beliefs entirely outside the Christian tradition, and is sometimes denominationally united with Unitarianism. The Jehovah's Witnesses are another expressly nontrinitarian group, but fall more properly into the category of a Restorationist movement. Other more recent nontrinitarian movements have emerged in the twentieth century. For example, the Unification Church holds a non-traditional idea of the Trinity, seeing God as both male and female, Jesus representing God's masculinity, and the Holy Spirit representing God's femininity.

Mainline and Evangelical Christians often reject nontrinitarian Christians on the grounds that the traditional doctrine of the Trinity is essential to Christian faith.

Restorationists

Strictly speaking, the Restoration Movement is a Christian reform movement that arose in the United States during the Second Great Awakening in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. It rejected the idea of reform of any previous tradition and emphasized the idea of a direct renewal of the Christian church by God.

The doctrinal differences among these groups can sometimes be very large; they include, among others, the Churches of Christ, Disciples of Christ, Christadelphians, Latter Day Saints, Seventh Day Adventists, and Jehovah's Witnesses.

Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism began in the United States early in the twentieth century, starting especially within the Holiness movement, seeking a return to the operation of New Testament gifts of the Holy Spirit and emphasizing speaking in tongues as evidence of the "baptism of the Holy Ghost." Divine healing and miracles were also emphasized.

Pentecostalism eventually spawned hundreds of new denominations, including large groups such as the Assemblies of God and the Church of God in Christ, both in the United States and elsewhere. A later "charismatic" movement also stressed the gifts of the Spirit, but often operated within existing denominations, including even the Catholic Church.

Liberal and and neo-orthodox theology

Mainline Protestant theology went through dramatic changes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when liberal theology emerged in the wake of advances in biblical criticism, the history of religions movement, and biblical archaeology. German theologians like Friedrich Schleiermacher, Albrecht Ritschl, and Adolf von Harnack led a trend in which Jesus was seen more as a teacher and example of moral virtue than a savior. The American Horace Bushnell also represented this trend, and later Walter Rauschenbusch developed it in the Social Gospel movement.

Beginning in 1918, the Germans Karl Barth and Emil Brunner reacted against the liberal trend through what became known as Neoorthodoxy, while the American Reinhold Niebuhr exposed the failures of liberal theology as applied to society and politics. Rudolf Bultmann, meanwhile responded to neo-orthodoxy in an attempt to uncover the core truths truth of the original Christian faith apart from later dogma through "demythologization."

By the 1960s, Protestant theology faced a crisis with various movements emerging, among them the theology of hope, radical theology, process theology, feminist theology, and Protestant liberation theology.

Ecumenism

Various attempts to unite the increasingly diverse traditions within Protestantism have met with limited success. The ecumenical movement has had an influence primarily on mainline churches, beginning by 1910, with the Edinburgh Missionary Conference. Its origins lay in the recognition of the need for cooperation on the mission field in Africa, Asia and Oceania. Since 1948, the World Council of Churches has been influential. There are also ecumenical bodies at regional, national and local levels across the globe. There has been a strong engagement of Orthodox churches in the ecumenical movement. The ecumenical movement has also made progress in bringing together Catholic, Orthodox, and Protest Churches.

One expression of the ecumenical movement, has been the move to form united churches, such as the US-based United Church of Christ, which brought together the Evangelical and Reformed Church and the Congregational Christian Churches. Similar unions took place through the formation of the United Church of Canada, the Uniting Church in Australia, the Church of South India, and the Church of North India.

See also

- Anabaptists

- Anglicanism

- Baptist Church

- Calvinism

- Congregationalism

- Christian Science

- Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Jehovah's Wintesses

- Lutheranism

- Methodism

- Pentecostalism

- Presbyterianism

- Quakerism

- Reformed churches

- Seventh Day Adventists

- Unitarianism

- Unification Church

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Marty, Martin E. Protestantism. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1972. ISBN 9780030913532.

- McGrath, Alister E., and Darren C. Marks. The Blackwell Companion to Protestantism. Blackwell companions to religion. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub, 2004. ISBN 9780631232780.

- Scott, William A. Historical Protestantism; An Historical Introduction to Protestant Theology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1970. ISBN 9780133892055.

External links

All links retrieved December 2, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.