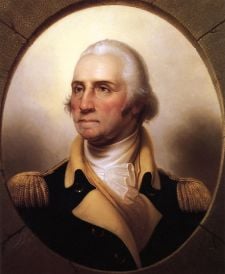

George Washington

| Term of office | April 30, 1789 – March 3, 1797 |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | John Adams |

| Date of birth | February 22, 1732 |

| Place of birth | Westmoreland County, Virginia |

| Date of death | December 14, 1799 |

| Place of death | Mount Vernon, Virginia |

| Spouse | Martha Custis Washington |

| Political party | None (1789-1793) Federalist (1793-1797) |

George Washington (February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799) was the commander in chief of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War from 1775 to 1783, and later the first president of the United States, an office to which he was twice elected unanimously (unanimous among the Electoral College) and held from 1789 to 1797.

Washington first gained prominence leading Virginia troops in support of the British Empire during the French and Indian War (1754–1763), a conflict which he inadvertently helped to start. After leading the American victory in the Revolutionary War, he refused to lead a military regime, though encouraged by some of his peers to do so. He returned to civilian life at his plantation at Mount Vernon, Virginia.

In 1787 he presided over the Constitutional Convention that drafted the current United States Constitution and, in 1789, was the unanimous choice to become the first president of the United States. His two-term administration set many policies and traditions that survive today. After his second term expired, Washington again voluntarily relinquished political power, thereby establishing an important precedent that was to serve as an example for the United States and also for other future republics.

Because of his central role in the founding of the United States, Washington is often called the “Father of the Nation.”[1] Many scholars rank him, with Abraham Lincoln, among the greatest of United States presidents.

Early life

According to the Julian calendar, Washington was born on February 11, 1731. The Gregorian calendar, which was adopted during Washington's lifetime and is used today, sets his birth date as February 22, 1732. Presidents' Day is celebrated on the Gregorian date. At the time of his birth, the English year began March 25 (Annunciation Day, or Lady Day), and hence the difference in his birth year. His birthplace was Popes Creek Plantation, on the Potomac River southeast of modern-day Colonial Beach in Westmoreland County, Virginia. His family had originated in and taken the name of the town of Washington, Tyne and Wear, a short distance from Newcastle upon Tyne in Northeastern England. In the 1500s, they moved to Sulgrave Manor in the county of Northamptonshire.

Washington was the oldest child from his father's second marriage. Washington had two older half-brothers: Lawrence and Augustine, Jr. "Austin," and four younger siblings: Betty, Samuel, John Augustine "Jack," and Charles. Washington's parents, Augustine Washington "Gus" (1693 – April 12, 1743) and Mary Ball Washington (1708 – August 25, 1789), were of British descent. Gus Washington was a slave-owning planter in Virginia who later tried his hand in iron-mining ventures. Considered members of the gentleman class, they were not nearly as wealthy as the neighboring Carters and Lees.

Washington spent much of his boyhood at Ferry Farm in Stafford County, Virginia, near Fredericksburg, and visited his Washington cousins at Chotank in King George County. One of Gus Washington's properties, where the family resided from 1735 to 1737, was Little Hunting Creek Farm. This property was later taken over by Gus's oldest son, Lawrence, and renamed Mount Vernon. Lawrence Washington had served as an officer in Gooch's Marines, the 61st Foot, which was under the British Admiral Edward Vernon's command in 1739 during the War of Jenkin's Ear. Lawrence continued to serve on Vernon's flagship as a captain of the Marines through 1741. He named his estate Mount Vernon in honor of his colorful and impressive commander.

Due to his family's level of prosperity Washington attended several schools, beginning his education when he was seven years old. The school was a cabin near Falmouth Church and was taught by the sexton "Hobby" Grove. He learned the basics of reading and writing, and when he was nine he was introduced to business and legal forms. A Virginia planter needed some knowledge of contracts and the law. As a student, Washington showed great promise. When he was ten, he was presented with a copy of the instructional workbook, The Young Man's Companion. This all-in-one manual supplied various business forms, lessons in construction, surveying and navigation at sea. [2]

The sudden death of his father in 1743 left the family in difficult circumstances and prevented young Washington from receiving an education in England as his older brothers Lawrence and Augustine had. Like their father before them, they had both attended Appleby School in England and George would have followed the tradition. He also turned down an offer of becoming a midshipman in the Royal Navy, which had been arranged by Lawrence. Washington’s older step brother was a faithful friend and sage adviser to him, but at the urging of his mother, 12-year-old Washington went instead to live with his older brother Augustine at the family home on Pope's Creek. There he attended Henry Williams School at Laurel Grove in Westmoreland County, Virginia. He began his formal studies in mathematics, business, and the practice of surveying which eventually became his first occupation.[3]

Washington returned to Ferry Farm across the Rappahannock from Fredericksburg in 1745. He had inherited the property and his mother and younger siblings lived there. Washington lived at Ferry Farm and Mount Vernon for the next several years. He was enrolled for a short time in a classical high school led by Reverend James Mayre. Mayre taught mathematics, Latin and deportment. Mayre had been born and raised in Rouen, France, and had studied with the Jesuit Order before renouncing Catholicism and reportedly fleeing to England where he became an Anglican cleric. It was during his first year with Mayre, in 1745, that young Washington wrote down his first manuscript version of what is now known as George Washington's Rules of Civility.[4]

Washington would never travel to Europe. His cobbled-together education was unlike Thomas Jefferson's who attended William and Mary College, or John Adam's, who went to Harvard. His education was average for Virginians of that time. If his spelling was casual, so it was with most of his peers. He learned to ride and shoot extremely well. Later he would be known as the finest horseman In America. His early reputation listed many accomplishments from organizing juvenile military companies to throwing stones and silver coins for great distances.[5]

French and Indian War, 1754–1763

At 22 years of age, Washington fired some of the first shots of what would become a world war. The trouble began in 1753, when France began building a series of forts in the Ohio Country, a region also claimed by Virginia. Robert Dinwiddie, the British lieutenant-governor of Virginia, had young Major Washington of the Virginia militia journey to the Ohio Country in order to deliver a letter to the French commander, which asked them to leave, and to assess French military strength and intentions. The French declined to leave, but Washington became well-known after his account of the journey was published in both Virginia and England, since most English-speaking people knew little about lands on the other side of the Appalachian Mountains at the time.

In 1754 Dinwiddie sent Washington—now commissioned a lieutenant colonel in the newly created Virginia Regiment—on another mission to the Ohio Country, this time to drive the French away. There, Washington and his troops ambushed a French Canadian scouting party. After a short skirmish, Washington's Native Amercian ally Tanacharison killed the wounded French commander, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. Washington then built Fort Necessity, which soon proved inadequate, as he was compelled to surrender at the Battle of the Great Meadows to a larger French and American Indian force. The surrender terms that Washington signed included an admission that he had "assassinated" Jumonville. The document was written in French, which Washington could not read. The Battle of Jumonville Glen and the "Jumonville affair" became an international incident and helped to ignite the French and Indian War, a part of the worldwide Seven Years' War. Washington was released by the French with his promise not to return to the Ohio Country for one year.

One year later, British General Edward Braddock headed a major effort to retake the Ohio Country, with Washington serving as Braddock's aide. The expedition ended in disaster at the Battle of the Monongahela River. Washington distinguished himself in the debacle. He had two horses shot out from under him, and four bullets pierced his coat, yet he sustained no injuries and showed coolness under fire in organizing the retreat. In Virginia, Washington was acclaimed as a hero, and he commanded the First Virginia Regiment for several more years, guarding the Virginia frontier against American Indian raids, although the focus of the war had shifted elsewhere. In 1758 he accompanied John Forbes and the Forbes Expedition, which successfully drove the French away from Fort Duquesne.

Washington's goal at the outset of his military career had been to secure a commission as a British officer, which had more prestige than serving in the provincial military. The promotion did not come, and so, in 1759, Washington resigned his commission and married Martha Dandridge Custis, a wealthy widow with two children. Washington raised her two children, John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis, affectionately called "Jacky" and "Patsy." Later the Washingtons raised two of Mrs. Washington's grandchildren, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis. Washington never fathered any children of his own due to an earlier bout with smallpox that may have made him sterile. The newlywed couple moved to Mount Vernon, where he took up the life of a gentleman farmer and slave owner. He held local office and was elected to the Virginia provincial legislature, the House of Burgesses.

American Revolution, 1774–1783

In 1774 Washington was chosen as a delegate from Virginia to the First Continental Congress, which convened in the wake of Britain's Intolerable Acts, which were punitive measures taken against the colony of Massachusetts. After fighting broke out at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Washington appeared at the Second Continental Congress in military uniform, signaling that he was prepared for war. To coordinate the military efforts of the Thirteen Colonies, the Congress created the Continental Army on June 14. The next day, it selected Washington as commander-in-chief. Massachusetts delegate John Adams nominated Washington, believing that appointing a southerner as notable and respected as Washington to lead (what was at this stage) primarily an army of northerners would help unite the colonies. Though reluctant to leave his home in Virginia, Washington accepted the command, declaring "with the utmost sincerity, I do not think my self equal to the Command I am honoured with." He asked for no pay other than reimbursement of his expenses.

Washington assumed command of the American forces in Massachusetts on July 3, 1775, during the ongoing siege of Boston. Washington reorganized the army during the long standoff, which finally ended on March 17, 1776, after artillery was placed upon the fortifications of Dorchester Heights. The ensuing cannonade forced the British evacuation of Boston for temporary refuge in the Halifax Regional Municipality in Canada. Washington then moved his army to New York City as a strategic move. New York was pro royalist and more centrally located than Boston within the 13 colonies.

In August 1776, British General William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe launched a successful campaign to capture New York, beginning a series of devastating defeats for Washington. He lost the Battle of Long Island on August 22, but managed to evacuate most of his forces to the mainland. Several other defeats sent Washington's forces scrambling across New Jersey, leaving the future of the Continental Army in doubt. On the night of December 25, 1776, Washington staged a celebrated counterattack, leading the American forces across the Delaware River to rout nearly one thousand Hessians in Trenton, New Jersey. Washington followed up the assault with a surprise attack on British forces at Battle of Princeton effectively breaking the tip of the spear of the British plans to strike quickly into Philadelphia and crush the rebellion. These unexpected victories after a series of losses gave the colonists cause to believe victory over the British Empire was possible. Many historians have cited the daring successes at Trenton and subsequently at Princeton as the turning point of the American Revolutionary War.

In 1777 British General Howe began a campaign to capture Philadelphia. Washington moved south to block Howe's army, but was defeated at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. On September 26, Howe outmaneuvered Washington and marched into Philadelphia unopposed. Washington's army unsuccessfully attacked the British garrison at Germantown in Philadelphia in early October and then retreated to the encampment at Valley Forge in December, where they stayed for the next six months. Over the winter, 2,500 men (out of ten thousand) died from disease and exposure. The next spring, however, the army emerged from Valley Forge in good order, thanks in part to a training program supervised by the Prussian general Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben.

Meanwhile, a second British expedition in 1777 had far-reaching consequences. General John Burgoyne had marched from Canada in an effort to sever New England from the other colonies, but was forced to surrender at the Battle of Saratoga due to the superior tactics of General Benedict Arnold on October 17. Reportedly, when one of Burgoyne's aides, shocked by the defeat asked the general, "What will history say?" Burgoyne's response was, "History, undoubtedly, will lie." This turn of events ultimately convinced France to sign a formal alliance with the United States in 1778. The victory at Saratoga was in stark contrast to Washington's loss of Philadelphia, prompting some members of Congress to secretly discuss removing Washington from command. This episode, which became known as the "Conway Cabal," failed due to the support of Washington's many allies.

French entry into the war changed everything. The British evacuated Philadelphia in 1778 and returned to New York City, with Washington attacking them along the way. Battle of Monmouth was the last major battle in the north. Thereafter, the British focused on recapturing control of the Southern colonies while fighting the French (and later, the Spanish and the Dutch) elsewhere around the globe. During this time, Washington remained with his army outside New York, himself headquartered in Rhode Island, looking for an opportunity to strike a decisive blow while dispatching other operations to the north and south. The long-awaited opportunity finally came in 1781, after a French naval victory on Chesapeake Bay which allowed American and French forces to trap a British army in Virginia. The siege and subsequent surrender at Yorktown on October 17, 1781, prompted the British to negotiate an end to the war. The Treaty of Paris officially recognized the independence of the United States.

Washington's contribution to victory in the American Revolution was not that of a great battlefield tactician; in fact, he lost more battles than he won—and he sometimes planned operations that were too complicated for his amateur soldiers to execute. However, his overall strategy proved to be the correct one: keep the army intact, wear down British resolve, and avoid decisive battles except to exploit enemy mistakes. Washington was a military conservative; he preferred building a regular army on the European model and fighting a conventional war.

One of Washington's most important contributions as commander-in-chief was to establish the precedent that civilian elected officials, rather than military officers, possessed ultimate authority over the military. Throughout the war, he deferred to the authority of Congress and state officials, and he relinquished his considerable military power once the fighting was over. In March 1783, Washington used his influence to disperse a group of army officers who had threatened to confront Congress regarding their back pay. Washington disbanded his army and, on November 2, gave an eloquent farewell address to his soldiers.[6] A few days later, the British forces evacuated New York City, and Washington and the governor took possession of the city. At Fraunces Tavern in the city on December 4, he formally bade his officers farewell. On December 23, 1783, Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief to the Congress of the Confederation.

Home in Virginia, 1783–1787

George Washington returned home to Mount Vernon, arriving at the gates of his estate around candlelight on Christmas Eve, 1783. He had been absent from his beloved home in service to his country since he assumed command of the Army in 1775. Waiting to greet him was his wife (to whom he had made the promise eight years prior that he would be home by Christmas) and four step-grandchildren, all born during his absence. The end of the war also took with it George Washington's stepson, Jacky Custis, who died of camp fever in 1781 at Yorktown.

Washington was persuaded to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, even though he was more reluctant to leave his wife and home than at the outset of the revolution. His troops had not been paid for their war service and the Confederacy lacked the power to raise the money. As usual, Washington did his homework in advance. His correspondence contains letters to several leaders soliciting their opinions about a new government. He was unanimously elected president of the convention. For the most part, he did not participate in the debates involved, but his prestige and dedication to the task kept the delegates at their labors when it looked as the convention would collapse. He adamantly enforced the secrecy adopted by the convention members. Many believe that the Founding Fathers of the United States created the presidency with Washington in mind. He was offered the title of king but rejected it. After the convention, his support convinced many, including the Virginia legislature, to support and adopt the Constitution.

Although Washington farmed roughly eight thousand acres (32 square kilometers), like many Virginia planters at the time, he had little cash on hand and was frequently in debt. He eventually had to borrow $600 to relocate to New York City, then the center of the American government, to take office as president.

Presidency, 1789–1797

Beginnings

Washington was elected unanimously by the Electoral College in the first United States presidential election in 1789, and he remains the only person ever to be elected president unanimously. He duplicated this feat in the second United States presidential election, 1792. As runner-up with 34 votes, John Adams—the man who nominated George Washington to lead the continental Army in 1775—then became vice president-elect of the United States. The First United States Congress voted to pay Washington a salary of $25,000 annually; a significant sum in 1789.

Washington was perhaps the wealthiest American at the time. His western lands were potentially valuable, but no one was living on them at that time. He declined his salary. It was part of his self-structured image as "Cincinnatus," the citizen who takes on the burdens of office as a civic duty. Washington attended carefully to the pomp and ceremony of office, making sure that the titles and trappings were suitably republican and never emulated European royal courts.

Washington's election was a disappointment to Martha Washington. Although she graciously accepted her role as the First Lady, she wanted to continue living in quiet retirement at Mount Vernon after the war. Nevertheless, she quickly assumed the role of hostess, opening her parlor and organizing weekly dinner parties for as many dignitaries as could fit around the presidential table.

Policies

In the beginning of his first term, Washington met individually with his advisers. It was not until 1791 that he held regular cabinet meetings. As president, Washington had to referee between the Treasury's Alexander Hamilton, who had bold plans to establish the national credit and build a financially powerful nation, and Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who usually opposed Hamilton. Hamilton won most of these battles, and after Washington denounced the Democratic-Republican societies as dangerous, he was hailed as the leading figure in the new United States Federalist Party. Jefferson chose the location of the new national capital, which would be located in the South, which was soon named "Washington, District of Columbia."

Congress imposed an excise tax on distilled spirits in 1791, which led to wide spread protests by the citizenry. A few years later in 1794, after Washington ordered the protesters to appear in United States district court, the protests turned into full-scale riots and outright rebellion. On August 7, Washington invoked the Militia Law of 1792 to summon the militias of Pennsylvania, Virginia and several other states to quell the Whiskey Rebellion. He raised an army of militiamen and marched at its head into the rebellious districts. There was no fighting, but Washington's forceful action proved the new government could protect itself. In leading the military force against the protestors, Washington became the only president to personally lead troops in battle. It also marked the first time under the new constitution that the federal government had used strong military force to exert authority over the states and citizens.

In recognition of the new nation, the revolutionary government of France sent diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt to America in 1793. Genêt attempted to turn popular sentiment towards American involvement in the war against Great Britain. Genêt was authorized to issue letters of marque and reprisal to American ships and gave authority to any French consulate-general to serve as a prize court. Genêt's activities forced Washington to ask the French government for his recall.

The Jay Treaty—named after Chief Justice of the United States John Jay, whom Washington sent to London to negotiate an agreement—was a treaty between the United States and Great Britain signed on November 19, 1794. The treaty attempted to clear up some of the lingering problems of American separation from Great Britain following the American Revolutionary War. Jeffersonians supported France and strongly attacked the treaty. Washington, however, obtained its ratification by Congress, which was supported by Hamilton. By its ratification, the British vacated their forts around the Great Lakes known as the Northwest Territory. The treaty remained effective until the War of 1812.

Hamilton used patronage to set up a network of friends of the administration. This developed into a full-fledged political party with Hamilton as the key leader. The Federalist Party elected John Adams president in 1796. Washington himself spoke often against the ills of political parties and thus never declared his support one way or the other. He did, however, support Hamilton's politics over Jefferson's, but he never made a statement to that effect. Washington did not become a member of any political party.

Washington had to be persuaded into a second term of office as president, and he reluctantly agreed. However, after two terms, Washington refused to stand for a third. By refusing a third term, Washington established a firm but unwritten precedent of a maximum of two terms for a U.S. president. It was not broken until Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1940. After Roosevelt's death, a two term maximum was formally integrated into the Federal Constitution by the 22nd Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Washington's Farewell Address (issued as a public letter) was the defining statement of Federalist party principles and one of the most influential statements of American political values. Most of the address dealt with the dangers of bitter partisanship in domestic politics. He called for men to put aside party affiliations and unite for the common good and for an America wholly free of foreign attachments, stating that the United States must concentrate only on American interests. He counseled friendship and commerce with all nations and warned sternly against involvement in European wars. Long-term alliances should be avoided, he said, but the 1778 alliance with France had to be observed. The address quickly entered the realm of "received wisdom." Many Americans, especially in subsequent generations, accepted Washington's advice as mandated fact and, in any debate between neutrality and involvement in foreign issues, would invoke the message as dispositive of all questions. Not until 1949 would the United States again sign a treaty of alliance with a foreign nation.

At John Adams' presidential inauguration, Washington is said to have approached Adams afterwards and state, "Well, I am fairly out and you are fairly in. Now we shall see who enjoys it the most!" Washington declined to leave the room before Adams and the new vice president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, established the principle that a former president is a private citizen.

States that Ratified the Constitution

- North Carolina (1789), part of confederation from 1777; 12th to ratify U.S. Constitution

- Rhode Island (1790), part of confederation from 1777; 13th to ratify U.S. Constitution

- Vermont (1791), independent Republic of Vermont, 1777–1791, was not part of confederation under the first constitution (Articles of Confederation); 14th state to ratify the U.S. Constitution and only state after the original 13 to do so

Retirement and death

After retiring from the presidency in March 1797, Washington returned to Mount Vernon with a profound sense of relief. He established a distillery there and became probably the largest distiller of whiskey in the nation at the time, producing 11,000 gallons (42,000 liters) of whiskey and a profit of $7,500 in 1798.

During 1798, Washington was appointed lieutenant general in the United States Army (then the highest possible rank) by President John Adams. Washington's appointment was to serve as a warning to France, with which war seemed imminent. While Washington never actively served, upon his death one year later, the U.S. Army rolls listed him as a retired lieutenant general, which was then considered the equivalent to his rank as general and commander in chief during the Revolutionary War.

Within a year of this 1798 appointment, Washington fell ill from a bad cold with a fever and a sore throat that turned into acute laryngitis and pneumonia; he died on December 14, 1799, at his home. Modern doctors believe that Washington died from either acute epiglottitis (supraglottitis) or, since he was bled as part of the treatment, a combination of asphyxia, dehydration, and shock from the loss of five pints of blood. One of the physicians who administered bloodletting to him was Dr. James Craik, one of Washington's closest friends who had been with Washington at Fort Necessity, the Braddock expedition, and throughout the Revolutionary War. Washington's remains were buried at Mount Vernon.

Thomas Jefferson wrote of Washington, "His integrity was the most pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known. He was indeed, in every sense of the word, a wise, a good and a great man."

Legacy

Congressman Henry Lee, a Revolutionary War comrade, famously eulogized Washington as, "a citizen, first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen."

Washington set many precedents that established tranquility in the presidential office in the years to come. His choice to peacefully relinquish the presidency to John Adams, after serving two terms in office, is seen as one of Washington's most important legacies.

He was also lauded as the "Father of His Country" and is often considered to be the most important of Founding Fathers of the United States. He has gained fame around the world as a quintessential example of a benevolent national founder. Americans often refer to men in other nations considered the Father of the Nation as "the George Washington of his nation" (for example, Mohandas K. Gandhi's role in India).

Washington is ranked number 26 in Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history. Historians generally regarded him as one of the greatest presidents.

Washington was the highest-ranking officer of the Revolutionary War, having in 1798 been appointed a lieutenant general (three-star). Since then, it seemed somewhat incongruent that all later full four-star and all five-star generals were considered to outrank Washington. This issue was resolved in 1976 when Washington was, by act of Congress, posthumously promoted to the rank of General of the Armies, outranking any past, present, and future general, and declared to permanently be the top-ranked military officer of the United States.

Summary of military career

- 1753: Washington appointed the rank of major in the Virginia Militia.

- 1754: Commissioned a Lieutenant Colonel in the Virginia Regiment (a full-time unit, not militia), and became colonel after death of Colonel Joshua Fry. He fought at the Battle of Jumonville Glen and the Battle of Great Meadows at Fort Necessity.

- 1755: Accompanied the disastrous Braddock expedition. Later, he was promoted to commander in chief of all Virginia forces.

- 1758: Commanded the Virginia Regiment in the Forbes expedition.

- 1759–1775: Retired from active military service.

- June 1775: Commissioned General and Commander in Chief of the Continental Army.

- 1775–1781: Commanded the Continental Army in more than seven major battles with the British.

- December 1783: Resigned commission as commander in chief of the army.

- July 1798: Appointed lieutenant general and commander of the Provisional Army to be raised in the event of a war with France.

- December 14, 1799: Died and was listed as a lieutenant general on the U.S. Army rolls.

- January 19, 1976: Approved by the United States Congress for promotion to general of the armies.

- October 11, 1976: Declared the senior most U.S. military officer for all time by Presidential Order of Gerald Ford.

- March 13, 1978: Promoted by Army Order 31–3 to general of the armies with effective date of rank July 4, 1776.

Personal qualities

Washington was long considered not just a military and revolutionary hero, but a man of great personal integrity, with a deeply held sense of duty, honor and patriotism. He was upheld as a shining example in schoolbooks and lessons as courageous and farsighted, holding the Continental Army together through eight hard years of war and numerous privations, sometimes by sheer force of will. At war's end he took affront at the notion he should be king, and after two terms as president, stepped aside, figuratively and literally, deferring to John Adams and newly-sworn Vice President Thomas Jefferson.

Traditionally, students have been taught to look to Washington as a character model more even than war hero or founding father. To them, Washington was notable for his modesty and carefully controlled ambition. It is true Washington never accepted pay during his military service with the Continental Army and was genuinely reluctant to assume any of the offices thrust upon him. When John Adams recommended him to the Continental Congress for the position of general and commander in chief of the Continental Army, Washington left the room to allow any dissenters to freely voice their objections. In later accepting the post, Washington told the Congress that he was unworthy of the honor.

It is often said that one of Washington's greatest achievements was refraining from taking more power than was due. He was conscientious of maintaining a good reputation by avoiding political intrigue. He had no interest in nepotism or cronyism, rejecting, for example, a military promotion during the war for his deserving cousin William Washington lest it be regarded as favoritism. Thomas Jefferson wrote, "The moderation and virtue of a single character probably prevented this Revolution from being closed, as most others have been, by a subversion of that liberty it was intended to establish."

Washington and slavery

Historians' perceptions of Washington's stand on slavery tend to be mixed.[7] Although Washington never made any public statement about slavery or the treatment of slaves, it is clear that as he progressed in life, he became increasingly uneasy with the "peculiar institution," and historian Roger Bruns wrote: "As he grew older, he became increasingly aware that it was immoral and unjust."

According to historians such as Clayborne Carson and Gary Nash, Washington's professed hatred of slavery was offset by his denial of freedom to even those slaves, like William "Billy" Lee, who fought with Washington for eight years. Lee lived at Mount Vernon as a slave, although his wife was a free woman from Philadelphia, named Margaret Thomas. Although some historians claim that it is not known whether she lived with him on the plantation,[8] most sources indicate that she did not.[9] Billy Lee was the only slave freed outright in Washington's will.

After the revolution, Washington told an English visitor, "I clearly foresee that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our [Federal] union by consolidating it on a common bond of principle." The buying and selling of slaves, as if they were "cattle in the market," especially outraged him. He wrote to his friend John Francis Mercer in 1786, "I never mean … to possess another slave by purchase; it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by which slavery in this country may be abolished by slow, sure, and imperceptible degrees." [10] Ten years later he wrote to Robert Morris: "There is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see some plan adopted for the abolition [of slavery]."[11]

As president, Washington was mindful of the risk of splitting apart the young republic over the question of slavery. He did not advocate the abolition of slavery while in office, but he signed legislation enforcing the prohibition of slavery in the Northwest Territory, writing to his good friend and Revolutionary War comrade, Marquis de la Fayette that he considered it a wise measure. Lafayette urged him to free his slaves as an example to others. Washington was held in such high regard after the revolution that there was reason to hope that if he freed his slaves, others would follow his example. Lafayette purchased an estate in French Guiana and settled his own slaves there, and he offered a place for Washington's slaves, writing, "I would never have drawn my sword in the cause of America if I could have conceived thereby that I was founding a land of slavery." Washington did not free his slaves in his lifetime but included a provision in his will to free the slaves upon the death of his wife. Martha Washington did not wait on this, and instead freed the Washington slaves on January 1, 1801. Billy Lee was the only slave freed outright upon George Washington's death.

One of Washington's slaves, Oney Judge Staines, escaped the Executive Mansion in Philadelphia in 1796 and lived the rest of her life free in New Hampshire.[12]

Religious beliefs

Washington's religious views are a matter of some controversy. He was an Episcopalian, but like numerous other educated men of the Enlightenment, he was influenced by Deism. As a young man before the revolution, when the Church of England was still the state religion in Virginia, he served as a vestryman (lay officer) for his local church. He spoke often of the value of prayer, righteousness, and seeking and offering thanks for the "blessings of Heaven." He frequently attended Christian church services; although it is said that he would regularly leave services before communion—with the other non-communicants. When Episcopalian Rev. Dr. James Abercrombie, the rector of St. Peter's Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, mentioned in a weekly sermon that those in elevated stations set an unhappy example by leaving at communion, Washington ceased attending on communion Sundays. Long after Washington died, when asked about Washington's beliefs, Abercrombie replied: "Sir, Washington was a Deist!" Various prayers said to have been composed by him in his later life are highly edited. He did not ask for any clergy on his deathbed, though one was available.

Washington was an active Freemason, as were many members of the aristocracy of his time (50 of the 55 signers of the Constitution were Freemasons). It is said that he would not promote anyone to the rank of general who was not a Freemason, and he took his first oath of office as president of the United States on a Masonic Bible. His funeral services were those of the Freemasons at his wife's request.

Like Benjamin Franklin, Washington was an early supporter of religious pluralism. In 1775, he ordered that his troops should not burn the pope in effigy on Guy Fawkes Night. In 1790 he wrote to Jewish leaders that he envisioned a country "which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance…. May the Children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid."

Washington's "Farewell Address To the People of the United States" as he left the presidency and retired from public office offered wisdom about religion that transcends disputes over doctrines and sacraments. He wrote:

Of all the dispositions and habits, which lead to political prosperity, Religion and Morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of Patriotism, who should labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of Men and Citizens. The mere Politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and to cherish them. A volume could not trace all their connexions with private and public felicity. Let it simply be asked, Where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths, which are the instruments of investigation in Courts of Justice? And let us with caution indulge the supposition, that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect, that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.[13]

Prayers and a Vision

Although the formal historical record lacks specifics about Washington's personal spiritual practices, his recorded public statements express views about divine authority that would be fully consistent with a man who privately communicated in prayer with his god. His "Circular Letter Addressed to the Governors of all the States on the Disbanding of the Army, June 14, 1783" is explicit:

I now make it my earnest prayer that God would have you, and the State over which you preside, in his holy protection; that he would incline the hearts of the citizens to cultivate a spirit of subordination and obedience to government, to entertain a brotherly affection and love for one another, for their fellow-citizens of the United States at large, and particularly for brethren who have served in the field; and finally that he would most graciously be pleased to dispose us all to do justice, to love mercy, and to demean ourselves with that charity, humility, and pacific temper of mind, which were the characteristics of the Divine Author of our blessed religion, and without an humble imitation of whose example in these things, we can never hope to be a happy nation.[14]

Anecdotal evidence of Washington's direct spirituality comes from the awful winter of 1777-1778 that he spent with his troops camped at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. The stories tell of a general who prayed desperately for divine guidance and support as disease and cold stole away one fourth of his troops. They also tell of a general who saw a striking vision for the future of the nation he was fighting to establish.

The stories of Washington in prayer trace back apparently to two independent incidents. In one a young Quaker man, Isaac Potts, who happened upon Washington praying aloud and alone in the woods was so moved by the general's sincerity and passion that he renounced his strict Quaker pacifism and became a supporter of the war. The second incident, reported by a man who wrote down stories he had heard from aging Continental soldiers, tells of the French general the Marquis de Lafayette and an American general who together happened upon General Washington knelt in deep silent prayer inside a horse barn. The two men reportedly observed the scene, closed the barn door, walked silently away and then conducted a serious conversation about how much they admired General Washington for seeking divine guidance and support in the conduct of the war. [15]

The vision that Washington was reported to have seen while at Valley Forge and to have recounted to a Continental Army soldier who wrote about it in his journal was reported in the National Tribune in 1880. The "Vision of Washington" at Valley Forge is a long and vivid account of a presumed visit to Washington by a "singularly beautiful female" who several times commanded him, "Son of the Republic, look and learn." In this way, Washington is reported to have seen several very different scenes depicting the birth, progress, and destiny of the United States.[16]

Public offices held

- Surveyor for Culpeper County, Virginia

- General Braddock's aide-de-camp in the French and Indian War, 1755

- Named commander in chief of the Virginia militia, 1755

- Elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, 1759

- Unanimously chosen commander in chief of the Continental Army, June 1775

- Masterminded the American victory at Yorktown, October 1781

- Unanimously elected president of the Constitutional Convention, 1787

- Unanimously elected president of the United States twice, 1789 and 1792

Trivia

- George Washington was almost six feet three inches (190 centimeters) tall and had red hair

- A popular belief is that Washington wore a wig, as was the fashion among some at the time. He did not wear a wig; he did, however, powder his hair,[17] as represented in several portraits, including the well-known unfinished Gilbert Stuart depiction.[18]

- It has been suggested in the journal Fertility and Sterility [19] that Washington had no children because he was sterile, most probably resulting from a case of tuberculosis; he seemingly contracted it from his brother who later died from the disease when he went to Barbados at age 19. His wife Martha had four children from a previous marriage (two died before they were four, the others died at age 16 and 28, respectively. Because Mrs. Washington had four children of her own, it is generally assumed that she was capable of having more children. However, childbirth was extremely difficult in Washington's day and any labor could cause irrevocable damage to a mother's ability to have more offspring. Mrs. Washington also suffered a case of the German measles shortly after her marriage to George. Either the difficult birth of her last child, Patsy, and or the measles could have compromised Mrs. Washington's fertility. The Washingtons, however, were surrounded by children. In addition to Mrs. Washington's son and daughter, two of her four grandchildren were raised by George and Martha Washington, and many nieces, nephews, and custodial wards came under the care of the Washington couple. The children of Mount Vernon include: John Parke Custis (son), Martha Parke Custis (daughter), Amelia Posey (ward), Frances Bassett (niece), George Augustine Washington (nephew), Harriot Washington (niece), Eleanor Parke Custis, (granddaughter), George Washington Parke Custis (grandson), and George Washington Lafayette (ward/son of the Marquis who lived with the Washingtons during the French Reign of Terror).

- Several younger men were essentially surrogate sons to the childless Washington, including Alexander Hamilton, Lafayette, Nathanael Greene, and George Washington Parke Custis, Washington's step-grandson whose daughter Mary became the wife of General Robert E. Lee.

- Washington was a cricket enthusiast and was known to have played the sport, which was popular at that time in the British colonies.

- Through his father's family, Washington was a direct descendant of King Edward III and William the Conqueror of England.[20] A cousin of George Washington was Lieutenant General Jakob Freiherr von Washington, knight commander of the Order of the Bath.

- One story about Washington has him throwing a silver dollar across the Potomac River. He may have thrown an object across the Rappahannock River, the river on which his childhood home, Ferry Farm, stood. However, the Potomac is over a mile wide at Mount Vernon.

- Washington's teeth were not made out of wood, as usually said. They were made out of teeth from different kinds of animals, specifically elk, hippopotamus, and human.[21] One set of false teeth that he had weighed almost four ounces (110 grams) and were made out of lead.

- In the first presidential inauguration, Washington took the oath as prescribed by the Constitution. Before taking his oath of office, a Masonic Bible was hurriedly borrowed on which to take the oath. Upon completing the oath, Washington leaned over and kissed the Bible.

- While Washington did not accept pay while the commander of the Continental Army, he did claim expenses. He provided Congress with a complete expense account which, after some grumbling, Congress paid in full.

- An attempt was made to kidnap Washington while he was commander-in-chief of the army during the American Revolution. The governor of New York, William Tryon, and the mayor of New York City, David Matthews, both Tories, were involved in the plot, as was one of Washington's bodyguards, Thomas Hickey. Hickey was court-martialed and hanged for mutiny, sedition, and treachery, on June 28, 1776.

- Washington, a Freemason, participated in the laying of the cornerstone of the Capitol Building as a Mason. He was master of Alexandria Masonic Lodge and was buried with Masonic honors. He was even suggested for the position of general grand master of Masons in America (which he did not pursue). It is generally accepted that if he would have taken the position that the individual state grand lodges would have united into one Grand Lodge of the United States.

- Washington was considered to be the finest horseman of his day. One of his favorite horses was named Nelson.

- The most famous man of his day, Washington received hundreds of guests to his home every year. In 1798, 677 visitors passed through Mount Vernon. Washington compared his home to a "well-resorted tavern."

- Washington was referred to as General Washington and not President Washington once he retired from the executive office. General was the title he preferred and protocol dictates that there is only one president. All former presidents return to their previous highest ranking title.

- Mrs. Washington burned the correspondence between her husband and herself following his death. Only three letters survived—two addressed from General Washington to Mrs. Washington and one from Mrs. Washington to the General.

Notes

- ↑ The earliest known image in which Washington is identified as such is on the cover of the 1778 Pennsylvania German almanac (Lancaster: Gedruckt bey Francis Bailey). This identifies Washington as Landes Vater or “Father of the Land.”

- ↑ John T. Phillips II, (ed.). George Washington's Rules of Civility: Complete With the Original French Text and New French-To-English Translations. (Leesburg, VA: Goose Creek Productions. ISBN 0965675874), 10-11.

- ↑ Phillips, 11.

- ↑ Phillips, 11-12.

- ↑ Marcus Cunliffe. George Washington and the Making of a Nation. (New York: American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc., 1966. ASIN B000JRBT3Q)

- ↑ George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799: Series 3b Varic. Library of Congress. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- ↑ “George Washington and Slavery.” Speech by Brian E. Frosh to Maryland State Senate. February 22, 2002. Retrieved April 22, 2006.

- ↑ William Lee: George Washington’s Valet. George Washington’s Mount Vernon Estate and Gardens. Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- ↑ Questions — A Last Word on Slavery: George Washington’s Will. The Papers of George Washington. Alderman Library, University of Virginia. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- ↑ George Washington to John F. Mercer, September 9, 1786. George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- ↑ George Washington to Robert Morris, April 12, 1786. George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- ↑ Edward Lawler, Jr., “Oney Judge.” Independence Hall Association ushistory.org. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- ↑ "George Washington's Farewell Address to the People of the United States" Archiving Early America. Retrieved July 12, 2007

- ↑ Washington's "Earnest Prayer" Historic Valley Forge. Retrieved July 12, 2007

- ↑ Washington's Prayer Historic Valley Forge. Retrieved July 12, 2007

- ↑ Washington's Vision Historic Valley Forge. Retrieved July 12, 2007

- ↑ George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- ↑ George Washington by Gilbert Stuart. National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- ↑ Fertility and Sterility asrm.org. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

- ↑ Washington Ancestry. AncestryUK.com. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

- ↑ Barbara Glover, 1998. “George Washington – A Dental Victim.” Americanrevolution.org. Retrieved May 23, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Comora, Madeleine & Deborah Chandra. George Washington's Teeth. Illustrated by Brock Cole. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003. ISBN 0374325340 A lighthearted chronicle of his dental struggles, aimed at children and adults

- Cunliffe, Marcus. George Washington and the Making of a Nation. New York: American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc., 1966. ASIN B000JRBT3Q

- Deconde, Alexander. Entangling Alliance: Politics & Diplomacy under George Washington. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1974. ISBN 0837172322

- Ellis, Joseph J. His Excellency: George Washington. New York: Knopf, 2004. ISBN 1400040310 Powerful interpretation of Washington's career

- Elkins, Stanley M. and Eric McKitrick. The Age of Federalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 019509381X The leading scholarly history of the 1790s

- Ferling, John E. The First of Men: A Life of George. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1989. ISBN 087049628X

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0195170342 Prize-winning military history focused on 1775-1776

- Flexner, James Thomas. Washington: The Indispensable Man. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co., 1994. ISBN 0316286168

- Flexner, James Thomas. George Washington: the Forge of Experience, 1732-1775. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co., 2006. ISBN 0316285978

- Freeman, Douglas S. Washington. New York, NY: Scribner, 1995. ISBN 0684826372 The standard scholarly biography abridged from seven volumes

- Grizzard, Frank E., Jr. George! A Guide to All Things Washington. Buena Vista and Charlottesville, VA: Mariner Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0976823802.

- Grizzard, Frank E., Jr. The Ways of Providence: Religion and George Washington. Buena Vista and Charlottesville, VA: Mariner Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0976823810

- Higginbotham, Don (ed.). George Washington Reconsidered. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2001. ISBN 081392006X

- Lengel, Edward G. General George Washington: A Military Life. New York: Random House, 2005. ISBN 1400060818

- Lodge, Henry C. George Washington. (Vol. 2, 1899, covers 1783-1799). Available online at Project Gutenberg. Retrieved November 17, 2022

- McDonald, Forrest. The Presidency of George Washington. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1988 (1974). ISBN 070060359X Intellectual history showing Washington as exemplar of republicanism.

- Peterson, Barbara Bennett. George Washington: America's Moral Exemplar. Huntington, NY: Nova History Publications, 2005. ISBN 1594542309

- Phillips II, John T. (ed.). George Washington's Rules of Civility: Complete With the Original French Text and New French-To-English Translations. Leesburg, VA: Goose Creek Productions, 1999. ISBN 0965675874

- Washington, George and Marvin Kitman. George Washington's Expense Account. New York: Grove Press, 2001. ISBN 0802137733 Account pages, with added humor

- Wiencek, Henry. An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2003. ISBN 0374529515

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2017.

The literature on George Washington is immense. The Library of Congress has a comprehensive bibliography online.

Biography

- George Washington Biography – American Presidents on History Empire

- George Washington archontology.org

Papers, Speeches and Texts

- Papers of Washington Full versions online, University of Virginia

- Papers of Washington The Avalon Project at Yale Law School

- Library of Congress: Washington's Commission as Commander in Chief

- 1st State of the Union Address

- 2nd State of the Union Address

- 3rd State of the Union Address

- 4th State of the Union Address

- 5th State of the Union Address

- 6th State of the Union Address

- 7th State of the Union Address

- 8th State of the Union Address

Other

- George Washington and Deism Deism.com

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.