Siege

| War |

| History of war |

| Types of War |

| Civil war · Total war |

| Battlespace |

| Air · Information · Land · Sea · Space |

| Theaters |

| Arctic · Cyberspace · Desert Jungle · Mountain · Urban |

| Weapons |

| Armored · Artillery · Biological · Cavalry Chemical · Electronic · Infantry · Mechanized · Nuclear · Psychological Radiological · Submarine |

| Tactics |

|

Amphibious · Asymmetric · Attrition |

| Organization |

|

Chain of command · Formations |

| Logistics |

|

Equipment · Materiel · Supply line |

| Law |

|

Court-martial · Laws of war · Occupation |

| Government and politics |

|

Conscription · Coup d'état |

| Military studies |

|

Military science · Philosophy of war |

A siege is a military blockade of a city or fortress with the intent of conquering by attrition and/or assault. Generally, the enemy begins by surrounding it, and then blocks reinforcements and supplies from entering it, or troops from escaping. Over time, sieges can demoralize fortress defenders, while attrition can occur through starvation, thirst, disease, and attacks. Fortifications can be reduced by means of siege engines, artillery bombardment, mining under walls, or bypassing defenses through trickery or treachery.

To defend themselves against sieges, even the earliest cities were fortified. Ancient cities in the Middle East show archaeological evidence of having had fortified city walls. From ancient times siege warfare dominated the conduct of war throughout the world. However, with the advent of gunpowder and the increasing use of ever more powerful cannon, the value of fortifications was diminished. With the advent of mobile warfare, one single fortified stronghold is no longer as decisive as it once was. By the twentieth century, the significance of the classical siege had declined, although some of the costliest sieges in history were still recorded then. Thus, while sieges do still occur, they are not as common as they once were due to changes in modes of battle, principally the ease by which huge volumes of destructive power can be directed onto a static target.

Siege warfare can be understood as a form of low-intensity warfare (at least until an assault takes place) characterized in that at least one party holds a strong defense position, it is highly static situation, the element of attrition is typically strong, and there are plenty of opportunities for negotiations. Nevertheless, sieges throughout history have claimed the lives of many, and not only those in the military, but also innocent citizens including women and children who took refuge within their fortified city believing it to be a place of safety. Thus, siege warfare is often barbaric, treating people with no respect or honor, with severe loss of life.

Purpose

Sieges are military efforts to conquer a city or fortress. The term derives from sedere, Latin for "to sit," since the attacking force sits and waits outside the surrounded city until they surrender. A siege occurs when an attacker encounters a city or fortress that cannot be easily taken by a coup de main and refuses to surrender. Sieges involve surrounding the target and blocking the reinforcement or escape of troops or provision of supplies (a tactic known as "investment," typically coupled with attempts to reduce the fortifications by means of siege engines, artillery bombardment, mining (also known as sapping), or the use of deception or treachery to bypass defenses. Failing a military outcome, sieges can often be decided by starvation, thirst, or disease, which can afflict both the attacker or defender.

Tactics

Siege methods

The most common practice of siege warfare is to lay siege and wait for the surrender of the enemies inside. This could take considerable time. For example, the Egyptian siege of Megiddo in the fifteenth century B.C.E. lasted for seven months before its inhabitants surrendered. The Hittite siege of a rebellious Anatolian vassal in the fourteenth century B.C.E. ended when the queen mother came out of the city and begged for mercy on behalf of her people.

If the main objective of a campaign was not the conquest of a particular city, it could simply be passed by. The Hittite campaign against the kingdom of Mitanni in the fourteenth century B.C.E. bypassed the fortified city of Carchemish. When the main objective of the campaign had been fulfilled, the Hittite army returned to Carchemish and the city fell after an eight-day-siege. The well-known Assyrian Siege of Jerusalem in the eighth century B.C.E. came to an end when the Israelites bought them off with gifts and tribute, according to the Assyrian account, or when the Assyrian camp was struck by mass death, according to the Biblical account. Due to the problem of logistics, long-lasting sieges involving only a minor force could seldom be maintained.

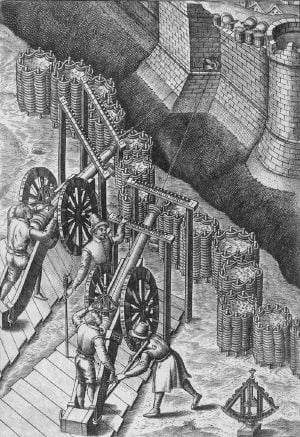

To end a siege more rapidly, various methods were developed in ancient and medieval times to counter fortifications, with a large variety of siege engines being developed for use by besieging armies. Ladders could be used to escalade over the defenses. Battering rams and siege hooks could be used to force through gates or walls, while catapults, ballistae, trebuchets, mangonels, and onagers could be used to launch projectiles in order to break down a city's fortifications and kill its defenders. A siege tower could also be used: a substantial structure built as high, or higher, than the walls, it allowed the attackers to fire down upon the defenders and also advance troops to the wall with less danger than using ladders.

In addition to launching projectiles at the fortifications or defenders, it was also quite common to attempt to undermine the fortifications, causing them to collapse. This could be accomplished by digging a tunnel beneath the foundations of the walls, and then deliberately collapsing or exploding the tunnel. This process is known as "mining." However, defenders could dig counter-tunnels to cut into the attackers' works and collapse them prematurely or use large bellows to pump smoke into the tunnels in order to suffocate the intruders.

Fire was often used as a weapon when dealing with wooden fortifications. The Byzantine Empire used Greek fire, which contained additives that made it hard to put out. Combined with a primitive flamethrower, it proved an effective offensive and defensive weapon.

Disease was another effective siege weapon, although the attackers were often as vulnerable as the defenders. In some instances, catapults or like weapons would fling diseased animals over city walls in an early example of biological warfare.

On occasion, a besieger could bribe the gate-keeper to gain entrance and thus claim his conquest undamaged, and retain his men and equipment intact.

'Forlorn hope'

In the days of muzzle-loading muskets, the term "forlorn hope" was frequently used to refer to the first wave of soldiers attacking a breach in defenses during a siege. It was likely that most members of this group would be killed or wounded, thus they had a "forlorn hope" of victory. The intention was that some would survive long enough to seize a foothold that could be reinforced, or at least that a second wave with better prospects could be sent in while the defenders were reloading or engaged in mopping up the remnants of the first wave.

A forlorn hope was typically led by a junior officer with hopes of personal advancement. If he survived, and performed courageously, he was almost guaranteed both a promotion and a long-term boost to his career prospects. As a result, despite the risks there was often competition for the opportunity to lead the assault. The French equivalent of the forlorn hope, called Les Enfants Perdus ("the lost children") were all guaranteed promotion to officers should they survive, so that both men and officers took up the suicidal mission as an opportunity to advance themselves in the army.

Means of defense

The universal method for defending against siege is the use of fortifications, principally walls and ditches to supplement natural features. A sufficient supply of food and water is also important to defeat the simplest method of siege warfare: starvation. During a siege, a surrounding army would build earthworks (a line of circumvallation) to completely encircle their target, preventing food and water supplies from reaching the besieged city. If sufficiently desperate as the siege progressed, defenders and civilians might be reduced to eating anything edible—horses, family pets, the leather from shoes, and even each other. On occasion, the defenders would drive "surplus" civilians out to reduce the demands on stored food and water.

Advances in the prosecution of sieges in ancient and medieval times naturally encouraged the development of a variety of defensive counter-measures. In particular, medieval fortifications became progressively stronger—for example, the advent of the concentric castle from the period of the Crusades—and more dangerous to attackers—witness the increasing use of machicolations and murder-holes, as well the preparation of hot or incendiary substances. Arrow slits (also called arrow loops or loopholes), sally ports (airlock like doors) for sallies, and deep-water wells were also integral means of resisting siege at this time. Particular attention would be paid to defending entrances, with gates protected by drawbridges, portcullises, and barbicans. Moats and other water defenses, whether natural or augmented, were also vital to defenders.

In the European Middle Ages, virtually all large cities had city walls—Dubrovnik in Dalmatia is an impressive and well-preserved example—and more important cities had citadels, forts, or castles. Great effort was expended to ensure a good water supply inside the city in case of siege. In some cases, long tunnels were constructed to carry water into the city. Complex systems of underground tunnels were used for storage and communications in medieval cities like Tábor in Bohemia (similar to those used much later in Vietnam during the Vietnam War).

Until the invention of gunpowder-based weapons (and the resulting higher-velocity projectiles), the balance of power and logistics definitely favored the defender. With the invention of gunpowder, cannon, and later mortars and howitzers, the traditional methods of defense became less and less effective against a determined siege.

Ancient era

The essential city walls

City walls and fortifications were essential for the defense of the first cities.

Settlements in the Indus Valley Civilization were often fortified. By about 3500 B.C.E., hundreds of small farming villages dotted the Indus floodplain. Many of these settlements had fortifications and planned streets. The stone and mud brick houses of Kot Diji were clustered behind massive stone flood dikes and defensive walls, since neighboring communities quarreled constantly about the control of prime agricultural land.

The Minoan civilization on Crete probably relied more on the defense of their outer borders or sea shores. Unlike the ancient Minoan civilization, the Mycenaean Greeks emphasized need for fortifications alongside natural defenses of mountainous terrain, such as the massive 'Cyclopean' walls built at Mycenae during the last half of the second millennium B.C.E.

In the ancient Near East city walls may have served the dual purpose of defense as well as showing presumptive enemies the might of the Kingdom. The great walls surrounding the Sumerian city of Uruk gained such a wide-spread reputation. The walls were 6 miles (9.7 km) in length, and raised up to 40 feet (12 m) in height. Later the walls of Babylon, reinforced by towers and moats, gained a similar reputation. In Anatolia, the Hittites built massive stone walls around their cities, taking advantage of the hillsides. In Shang Dynasty China, at the site of Ao, large walls were erected in the fifteenth century B.C.E. that had dimensions of 65 feet (20 m) in width at the base and enclosed an area of some 2,100 square yards (1,800 m²). The Chinese capital for the State of Zhao, Handan (founded in 386 B.C.E.), had walls that were again 65 feet (20 m) wide at the base, a height of 50 feet (15 m), with two separate sides of its rectangular enclosure measuring 1,530 square yards (1,280 m²).

Archaeological evidence

Although there are depictions of sieges from the ancient Near East in the historical sources and in ancient Near Eastern art, there are very few examples of siege systems (towers, trenches, and associated weaponry) that have been found archaeologically. Of the few examples, several are noteworthy:

The late-ninth century B.C.E. siege system surrounding Tell es-Safi/Gath, Israel. This system, which consists of a 1.6 miles (2.6 km) long siege trench, towers, and other elements—the earliest evidence of a circumvallation system known in the world—was apparently built by Hazael of Aram, Damascus, as part of his siege and conquest of the Philistine Gath mentioned in II Kings 12:18.

The late-eighth-century B.C.E. siege system surrounding the site of Lachish (Tell el-Duweir) in Israel. This system, which was built by Sennacherib of Assyria in 701 B.C.E., is not only evident in the archaeological remains, but is described in the Assyrian and biblical sources and in the reliefs of Sennacherib's palace in Nineveh.

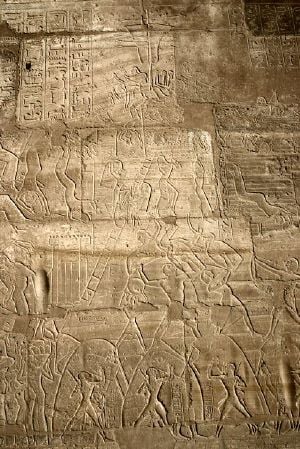

Depictions

The earliest representations of siege warfare are dated to the Protodynastic Period of Egypt, c.3000 B.C.E. These show symbolic destruction of city walls by divine animals using hoes. The first siege equipment is known from Egyptian tomb reliefs of the twenty-fourth century B.C.E., showing Egyptian soldiers storming Canaanite town walls on wheeled siege ladders. Later Egyptian temple reliefs of the thirteenth century B.C.E. portray the violent siege of Dapur, a Syrian city, with soldiers climbing scale ladders supported by archers. Assyrian palace reliefs of the ninth to seventh centuries B.C.E. display sieges of several Near Eastern cities. Though a simple battering ram had come into use in the previous millennium, the Assyrians improved siege warfare and built huge wooden tower shaped battering rams with archers positioned on top. In ancient China, sieges of city walls (along with naval battles) were portrayed on bronze hu vessels dated to the Warring States (fifth century B.C.E. to third century B.C.E.), like those found in Chengdu, Sichuan, China in 1965.

Siege accounts

Although there are numerous ancient accounts of cities being sacked, few contain any clues to how this was achieved. Some popular tales exist on how the cunning heroes succeeded in their sieges. The best-known is the Trojan Horse of the Trojan War, and a similar story tells how the Canaanite city of Joppa was conquered by the Egyptians in the fifteenth century B.C.E. The Biblical Book of Joshua contains the story of the miraculous Battle of Jericho. A detailed historical account from the eighth century B.C.E. Piankhi stela records how the Nubians laid siege to and conquered several Egyptian cities using battering rams, archers, slingers, and building causeways across moats.

Greco-Roman era

Alexander the Great's Macedonian army successfully besieged many powerful cities during his conquests. Two of his most impressive achievements in siegecraft took place at Siege of Tyre and the Sogdian Rock. Most conquerors before him had found Tyre, a Phoenician island-city about .6 miles (0.97 km) from the mainland, impregnable. The Macedonians built a mole, a raised spit of earth across the water, by piling stones up on a natural land-bridge that extended underwater out to the island. Then his engineers built a causeway and the soldiers pushed siege towers housing stone throwers and light catapults to bombard the city walls. Though the Tyrians rallied by sending a fire-bombed ship to destroy the towers, and captured the mole in a swarming frenzy, the city eventually fell to the Macedonians after a seven-month siege. In contrast to Tyre, Sogdian Rock was captured by stealthy attack. Alexander used commando-like tactics to scale the cliffs and capture the high ground. The demoralized defenders surrendered.

The importance of siege warfare in the ancient period should not be underestimated. One of the contributing causes of Hannibal's inability to defeat Rome was his lack of siege training; thus, while he was able to defeat Roman armies in the field, he was unable to capture Rome itself.

The legionary armies of the Roman Republic and Empire are noted as being particularly skilled and determined in siege warfare. An astonishing number and variety of sieges, for example, formed the core of Julius Caesar's mid-first-century B.C.E. conquest of Gaul (modern France). In his Gallic Wars, Caesar describes how at the Battle of Alesia the Roman legions created two huge fortified walls around the city. The inner circumvallation, 10 miles (16 km) long, held in Vercingetorix's forces, while the outer contravallation kept relief from reaching them. The Romans held the ground in between the two walls. The besieged Gauls, facing starvation, eventually surrendered after their relief force met defeat against Caesar's auxiliary cavalry.

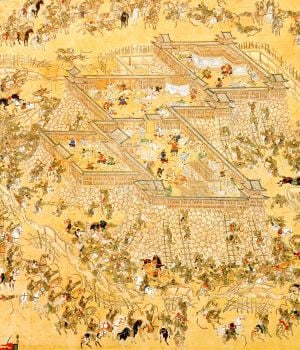

Chinese and Mongols

In the Middle Ages, the Mongol Empire's campaign against China (then comprising the Western Xia Dynasty, Jin Dynasty, and Southern Song Dynasty) by Genghis Khan until Kublai Khan, who eventually established the Yuan Dynasty in 1271 with their armies, was extremely effective, allowing the Mongols to sweep through large areas. Even if they could not enter some of the more well-fortified cities, they used 20 catapults against the Bab al-Iraq (Gate of Iraq) at the siege of Aleppo, Hulegu. There are several episodes in which the Mongols constructed a large number of siege machines in order to surpass the number which the defending city possessed.

Another Mongol tactic was to use catapults to launch corpses of plague victims into besieged cities. The disease-carrying fleas from the bodies would then infest the city, and the plague would spread allowing the city to be easily captured, although this transmission mechanism was not known at the time.

Some psychological warfare tactics were also used: On the first night while laying siege to a city, the leader of the Mongol forces would lead from a white tent: if the city surrendered, all would be spared. On the second day, he would use a red tent: if the city surrendered, the men would all be killed, but the rest would be spared. On the third day, he would use a black tent: no quarter would be given.

However, the Chinese were not defenseless, and from 1234 until 1279 C.E. the Southern Song Chinese held out against the enormous barrage of Mongol attacks. Much of this success in defense lay in the world's first use of gunpowder (with early flamethrowers, grenades, firearms, cannons, and land mines) to fight back against the Khitans, the Tanguts, the Jurchens, and then the Mongols. The Chinese of the Song period also discovered the explosive potential of packing hollowed cannonball shells with gunpowder.

During the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 C.E.), the Chinese were very concerned with city planning in regards to gunpowder warfare. The site for constructing the walls and the thickness of the walls in Beijing's Forbidden City were favored by the Chinese Yongle Emperor (r. 1402–1424)—, because they were positioned to resist cannon volley and were built thick enough to withstand attacks from cannon fire.

Age of gunpowder

The introduction of gunpowder and the use of cannons brought about a new age in siege warfare. Cannons were first used in Song Dynasty China during the early thirteenth century, but did not become significant weapons for another 150 years or so. By the sixteenth century, they were an essential and regularized part of any campaigning army, or castle's defenses.

The greatest advantage of cannons over other siege weapons was the ability to fire a heavier projectile, further, faster, and more often than previous weapons. They could also fire projectiles in a straight line, so that they could destroy the bases of high walls. Thus, "old fashioned" walls—that is high and, relatively, thin—were excellent targets and, over time, easily demolished. In 1453, the great walls of Constantinople were broken through in just six weeks by the 62 cannon of Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II's army.

Leonardo da Vinci, the Italian polymath, was renowned as an engineer and inventor. In Venice in 1499 he devised a system of movable barricades to protect the city from attack. He also had a scheme for diverting the flow of the Arno River in order to flood Pisa. His journals include a vast number of inventions, both practical and impractical. They include hydraulic pumps, reversible crank mechanisms, finned mortar shells, and a steam cannon. The castles that in earlier years had been formidable obstacles were easily breached by the new weapons. For example, in Spain, the newly equipped army of Ferdinand and Isabella was able to conquer Moorish strongholds in Granada in 1482-1492 that had held out for centuries before the invention of cannons.

Once siege guns were developed the techniques for assaulting a town or a fortress became well known and ritualized. The attacking army would surround a town. Then the town would be asked to surrender. If they did not comply the besieging army would surround the town with temporary fortifications to stop sallies from the stronghold or relief getting in. The attackers would then build a length of trenches parallel to the defenses and just out of range of the defending artillery. They would then dig a trench towards the town in a zigzag pattern so that it could not be enfiladed by defending fire. Once within artillery range, another parallel trench would be dug with gun emplacements. If necessary using the first artillery fire for cover, this process would be repeated until guns were close enough to be laid accurately to make a breach in the fortifications. In order to allow support troops to get close enough to exploit the breach, more zigzag trenches could be dug even closer to the walls with more parallel trenches to protect and conceal the attacking troops. After each step in the process, the besiegers would ask the besieged to surrender. If attacking troops stormed the breach successfully the defenders could expect no mercy.

New fortresses

In the early fifteenth century, Italian architect Leon Battista Alberti wrote a treatise entitled De Re aedificatoria which theorized methods of building fortifications capable of withstanding the new guns. He proposed that walls be "built in uneven lines, like the teeth of a saw." He proposed star-shaped fortresses with low thick walls.

However, few rulers paid any attention to his theories. A few towns in Italy began building in the new style late in the 1480s, but it was only with the French invasion of the Italian peninsula in 1494-1995 that the new fortifications were built on a large scale. Charles VIII invaded Italy with an army of 18,000 men and a horse-drawn siege-train. As a result he could defeat virtually any city or state, no matter how well defended. In a panic, military strategy was completely rethought throughout the Italian states of the time, with a strong emphasis on the new fortifications that could withstand a modern siege.

The most effective way to protect walls against cannon fire proved to be depth (increasing the width of the defenses) and angles (ensuring that attackers could only fire on walls at an oblique angle, not square on). Initially walls were lowered and backed, in front and behind, with earth. Towers were reformed into triangular bastions.

This design matured into the trace italienne. Star-shaped fortresses surrounding towns and even cities with outlying defenses proved very difficult to capture, even for a well- equipped army. Fortresses built in this style throughout the sixteenth century did not become fully obsolete until the nineteenth century, and were still in use throughout World War I (though modified for twentieth-century warfare).

However, the cost of building such vast modern fortifications was incredibly high, and was often too much for individual cities to undertake. Many were bankrupted in the process of building them; others, such as Siena, spent so much money on fortifications that they were unable to maintain their armies properly, and so lost their wars anyway. Nonetheless, innumerable large and impressive fortresses were built throughout northern Italy in the first decades of the sixteenth century to resist repeated French invasions that became known as the Italian Wars. Many stand to this day.

The Siege of Vienna in 1529 C.E. was the first attempt of the Ottoman Empire, led by Sultan Suleiman I, to capture the city of Vienna, Austria. In this case, the city walls of Vienna represented an impressive bulwark to the opposing forces. Traditionally, the siege held special significance in Western history, indicating the Ottoman Empire's highwater mark.

In the 1530s and 1540s, the new style of fortification began to spread out of Italy into the rest of Europe, particularly to France, the Netherlands, and Spain. Italian engineers were in enormous demand throughout Europe, especially in war-torn areas such as the Netherlands, which became dotted by towns encircled in modern fortifications. For many years, defensive and offensive tactics were well balanced leading to protracted and costly wars, involving more and more planning and government involvement.

The new fortresses ensured that war rarely extended beyond a series of sieges. Because the new fortresses could easily hold 10,000 men, an attacking army could not ignore a powerfully fortified position without serious risk of counterattack. As a result, virtually all towns had to be taken, and that was usually a long, drawn-out affair, potentially lasting from several months to years, while the members of the town were starved to death. One such bloody battle was the Siege of Malta (also known as the Great Siege of Malta), which took place in 1565 when the Ottoman Empire invaded the island, then held by the Knights Hospitaller. The Knights won the ensuing battle but the casualty rate was large. Most battles in this period were between besieging armies and relief columns sent to rescue the besieged.

Marshal Vauban

At the end of the seventeenth century, Marshal Vauban, a French military engineer, developed modern fortification to its pinnacle, refining siege warfare without fundamentally altering it: Ditches would be dug; walls would be protected by glacis; and bastions would enfilade an attacker.

He was also a master of planning sieges. Before Vauban, sieges had been somewhat slapdash operations. Vauban refined besieging to a science with a methodical process that, if uninterrupted, would break even the strongest fortifications.

Planning and maintaining a siege is just as difficult as fending one off. A besieging army must be prepared to repel both sorties from the besieged area and also any attack that may try to relieve the defenders. It was thus usual to construct lines of trenches and defenses facing in both directions. The outermost lines, known as the lines of contravallation, would surround the entire besieging army and protect it from attackers. This would be the first construction effort of a besieging army. A line of circumvallation would also be constructed, facing in towards the besieged area, to protect against sorties by the defenders and to prevent the besieged from escaping.

The next line, which Vauban usually placed at about 2,000 feet (610 m) from the target, would contain the main batteries of heavy cannons so that they could hit the target without being vulnerable themselves. Once this line was established, work crews would move forward creating another line at 820 feet (250 m). This line contained smaller guns. The final line would be constructed only 100 feet (30 m) to 200 feet (61 m) from the fortress. This line would contain the mortars and would act as a staging area for attack parties once the walls were breached. It would also be from there that miners working to undermine the fortress would operate.

The trenches connecting the various lines of the besiegers could not be built perpendicular to the walls of the fortress, as the defenders would have a clear line of fire along the whole trench. Thus, these lines (known as saps) needed to be sharply jagged.

Industrial advances

Advances in artillery made previously impregnable defenses useless. For example, the walls of Vienna that had held off the Turks in the mid-seventeenth century were no obstacle to Napoleon in the late eighteenth. Where sieges occurred (such as the Siege of Delhi and the Siege of Cawnpore during the Indian Rebellion of 1857), the attackers were usually able to defeat the defenses within a matter of days or weeks, rather than weeks or months as previously. The great Swedish white-elephant fortress of Karlsborg was built in the tradition of Vauban and intended as a reserve capital for Sweden, but it was obsolete before it was completed in 1869.

Railways, when they were introduced, made possible the movement and supply of larger armies than those that fought in the Napoleonic Wars. This also reintroduced siege warfare, as armies seeking to use railway lines in enemy territory were forced to capture fortresses which blocked these lines. During the Franco-Prussian War, the battlefield front-lines moved rapidly through France. However, the Prussian and other German armies were delayed for months at the Siege of Metz and the Siege of Paris, due to the greatly increased firepower of the defending infantry, and the principle of detached or semi-detached forts with heavy-caliber artillery. This resulted in the later construction of fortress works across Europe such as the massive fortifications at Verdun. It also led to the introduction of tactics which sought to induce surrender by bombarding the civilian population within a fortress rather than the defending works themselves.

The Siege of Sevastopol (1854-1855) during the Crimean War and the siege at Petersburg, Virginia (1864-1865) during the American Civil War showed that modern citadels, when improved by improvised defenses, could still resist an enemy for many months. The Siege of Pleven during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) proved that hastily constructed field defenses could resist attacks prepared without proper resources, and were a portent of the trench warfare of World War I.

The Siege of Malakand took place between July 26 to August 2, 1897, constituting a siege of the British garrison in the Malakand region of modern-day Pakistan's Northwest Frontier Province. The British faced a force of Pashtun tribesmen whose tribal lands had been bisected by the Durand Line, the 1,519-mile border between Afghan and British forces, which was established due to Anglo-Russian rivalry in the region. The siege was lifted when garrison forces were relieved by British troops with superior arms.

Advances in firearms technology without the necessary advances in battlefield communications gradually led to the defense again gaining the ascendancy. An example of siege during this time, prolonged during 337 days due to the isolation of the surrounded troops, was the Siege of Baler. A reduced group of Spanish soldiers was besieged in a small church by the Philippine rebels in the course of the Philippine Revolution and the Spanish-American War until months after the Treaty of Paris, the end of the conflict.

Furthermore, the development of steamships availed greater speed to blockade runners, ships with the purpose of bringing cargo, including food, to cities under blockade, as with Charleston, South Carolina during the American Civil War.

Modern warfare

Mainly as a result of the increasing firepower (such as machine guns) available to defensive forces, First World War trench warfare briefly revived a form of siege warfare. Trench warfare utilized many of the techniques of siege warfare in its prosecution (sapping, mining, barrage and, of course, attrition) but on a much larger scale and on a greatly extended front.

More traditional sieges of fortifications took place in addition to trench sieges. The Siege of Tsingtao was one of the first major sieges of the war, but the inability for significant resupply of the German garrison made it a relatively one-sided battle. The Germans and the crew of an Austro-Hungarian protected cruiser put up a hopeless defense and after holding out for more than a week surrendered to the Japanese, forcing the German East Asia Squadron to steam towards South America for a new coal source.

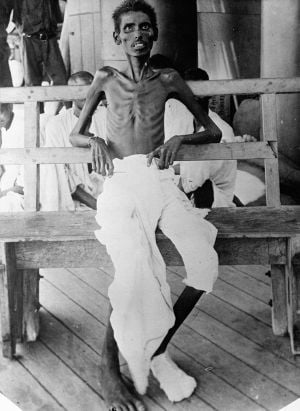

The other major siege outside Europe during the First World War was in Mesopotamia, at the Siege of Kut. After a failed attempt to move on Baghdad, stopped by the Ottomans at the bloody Battle of Ctesiphon, the British and their large contingent of Indian sepoy soldiers were forced to retreat to Kut, where the Ottomans under German General Baron Colmar von der Goltz laid siege. The British attempts to resupply the force via the Tigris river failed, and rationing was complicated by the refusal of many Indian troops to eat cattle products. By the time the garrison fell on April 29, 1916, starvation was rampant.

The largest sieges of the war, however, took place in Europe. The initial German advance into Belgium produced four major sieges, the Battle of Liege, the Battle of Namur, the Siege of Maubeuge and the Siege of Antwerp. All three would prove crushing German victories, at Liege and Namur against the Belgians, at Maubeuge against the French and at Antwerp against a combined Anglo-Belgian force. The weapon that made these victories possible were the German Big Berthas and the Skoda 305 mm Model 1911 siege mortars on loan from Austria-Hungary. These huge guns were the decisive weapon of siege warfare in the twentieth century, taking part at Przemysl, the Belgian sieges, on the Italian Front and Serbian Front, and even being reused in World War II.

At the second Siege of Przemysl the Austro-Hungarian garrison showed an excellent knowledge of siege warfare, not only waiting for relief, but sending sorties into Russian lines and employing an active defense that resulted in the capture of the Russian General Kornilov. Despite its excellent performance, the garrison's food supply had been requisitioned for earlier offensives, a relief expedition was stalled by the weather, ethnic rivalries flared up between the defending soldiers, and a breakout attempt failed. When the commander of the garrison Hermann Kusmanek finally surrendered, his troops were eating their horses and the first attempt of large-scale air supply had failed. Use of aircraft for siege running, bringing supplies to areas under siege, would nevertheless prove useful in many sieges to come.

The largest siege of World War I, and the arguably the roughest, most gruesome battle in history, was the Battle of Verdun. The main fortifications were Fort Douaumont, Fort Vaux, and the fortified city of Verdun itself. The Germans, through the use of a huge artillery bombardments, flamethrowers, and infiltration tactics, were able to capture both Forts Vaux and Douaumont, but were never able to take the city, and eventually lost most of their gains.

In World War II the Siege of Leningrad lasted over 29 months, about half of the duration of the entire war. Along with the Battle of Stalingrad, the Siege of Leningrad on the Eastern Front was the deadliest siege of a city in history. In the West, apart from the Battle of the Atlantic, the sieges were not on the same scale as those on the European Eastern front; however, there were several notable or critical sieges: the island of Malta for which the population won the George Cross, Tobruk, and Monte Cassino. In the South-East Asian Theatre there was the siege of Singapore and in the Burma Campaign sieges of Myitkyina, the Admin Box, and the Battle of the Tennis Court, which was the high water mark for the Japanese advance into India.

The airbridge methods which were developed and used extensively in the Burma Campaign for supplying the Chindits and other units, including those in sieges such as Imphal, as well as flying the Hump into China, allowed the Western powers to develop air-lift expertise that would prove vital during the Cold War Berlin Blockade.

During the Vietnam War, the battles of Dien Bien Phu (1954) and Khe Sanh (1968) possessed siege-like characteristics. In both cases, the Vietminh and National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF) were able to cut off the opposing army by capturing the surrounding rugged terrain. At Dien Bien Phu, the French were unable to use air power to overcome the siege and were defeated. However, at Khe Sanh a mere 14 years later, advances in air power allowed the United States to withstand the siege. The resistance of U.S. forces was assisted by the North Vietnamese Army (PAVN) and PLAF forces' decision to use the Khe Sanh siege as strategic distraction to allow their mobile warfare offensive, the first Tet offensive, to unfold securely. The Siege of Khe Sanh displays typical features of modern sieges, as the defender has greater capacity to withstand siege, the attacker's main aim is to bottle operational forces, or create a strategic distraction, rather than take a siege to conclusion.

Still, sieges have continued through the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century. From 1980 to April 11, 1991, during the Soviet war in Afghanistan, and subsequent Afghan Civil War, the city of Khost was under siege for more than 11 years. It is considered the longest siege in modern history.

Sarajevo, then controlled by the Bosnian government, was besieged by the Serb paramilitary from April 5, 1992 to February 29, 1996, in the Siege of Sarajevo.

The Siege of Sangin lasted from June 2006 to April 2007, during which time Taliban insurgents attempted to besiege the district center of Sangin District in Helmand Province, Afghanistan, occupied by British International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) soldiers.

Hostage situations

Despite the overwhelming might of the modern state, siege tactics continue to be employed in certain police conflicts, such as hostage situations. This is due to a number of factors, primarily risk to life, whether that of the police, the besieged, bystanders, or hostages. Police make use of trained negotiators, psychologists and, if necessary, force, generally being able to rely on the support of their nation's armed forces if required.

The 1993 police siege on the Branch Davidian church in Waco, Texas, lasted 51 days, an atypically long police siege. Unlike traditional military sieges, police sieges tend to last for hours or days rather than weeks, months, or years.

One of the complications facing police in a siege involving hostages is the Stockholm syndrome, whereby hostages can sometimes develop a sympathetic rapport with their captors. If this helps keep them safe from harm this is considered to be a good thing, but there have been cases where hostages have tried to shield the captors during an assault or refused to co-operate with the authorities in bringing prosecutions.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bartolon, Liana. 1988. The Life Times and Art of Leonardo. Crescent. ISBN 978-0517163030

- Duffy, Christopher. 1985. Siege Warfare, Volume II: The Fortress in the Age of Vauban and Frederick the Great. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0710096487

- Duffy, Christopher. 1996. Fire & Stone: The Science of Fortress Warfare. New York, NY: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-1853672477

- Duffy, Christopher. 1996. Siege Warfare: Fortress in the Early Modern World. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0415146496

- Ebrey, Patricia B., Anne Walthall, and James Palais. 2006. East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0618133852

- Lynn, John A. 1999. The Wars of Louis XIV. New York, NY: Longman. ISBN 978-0582056282

- Turnbull, Stephen R. 2002. Siege Weapons of the Far East. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1841763392

External links

All links retrieved May 15, 2023.

- Secrets of Lost Empires: Medieval Siege. companion Web site to the NOVA program "Medieval Siege"

- The 7 Most Incredible Sieges In Military History

- 10 Things You Probably Didn't Know about Sieges English Heritage

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.