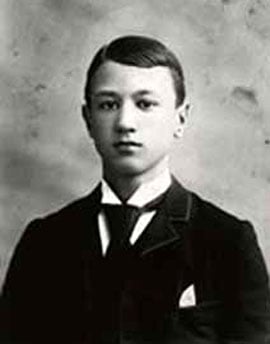

Charles Ives

| Charles Edward Ives | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Charles Edward Ives |

| Born | October 20, 1874, Danbury, Connecticut, United States |

| Died | May 19, 1954, New York City, New York |

| Occupation(s) | Composer, organist |

| Notable instrument(s) | |

| Composer organ | |

Charles Edward Ives (October 20, 1874 – May 19, 1954) was an American composer of European classical music. He is widely regarded as one of the first American classical composers of international significance. Ives' music was largely ignored during his life, and many of his works went unperformed for many years. Over time, Ives would come to be regarded as one of the "American Originals," a composer working in a uniquely American style, with American tunes woven through his music, and a reaching sense of the possibilities in music.

Ives' upbringing was imbued with religious music and he would often attend revival meetings in which Christian hymns were central to the worship service. Many of theses "old time" hymn tunes would find their way into his compositions and he often wrote music based on inherently Christian themes. The influence of one's personal faith on one's creative endeavors can be found through the annals of music history, and in this regard, Ives was not unlike Johann Sebastian Bach, George Frideric Handel, Ludwig van Beethoven, Anton Bruckner and a legion of other composers whose religious convictions would influence their work in profound ways.

Biography

Charles was born in Danbury, Connecticut, the son of George Ives, a United States Army band leader during the American Civil War, and his wife Mollie. A strong influence of Charles's may have been sitting in the Danbury town square, listening to his father's marching band and other bands on other sides of the square simultaneously. George Ives' unique music lessons were also a strong influence on Charles. George Ives took an open-minded approach to musical theory, encouraging his son to experiment in bitonal and polytonal harmonizations. Charles would often sing a song in one key, while his father accompanied in another key. It was from his father that Charles Ives also learned the music of Stephen Foster. Ives became a church organist at the age of 14 and wrote various hymns and songs for church services, including his Variations on 'America' .[1]

Ives moved to New Haven, Connecticut in 1893, graduating from the Hopkins School. Then, in September 1894, Ives went to Yale University, studying under Horatio Parker. Here he composed in a choral style similar to his mentor, writing church music and even an 1896 campaign song for William McKinley. On November 4, 1894, Charles's father died, a crushing blow to the young composer, who idealized his father, and to a large degree continued the musical experimentation begun by him. Ives undertook the standard course of study at Yale, studying a broad array of subjects, including Greek, Latin, mathematics and literature. He was a member of Delta Kappa Epsilon and Wolf's Head, a secret society, and sat as chairman of the Ivy League Committee. His works Calcium Light Night and Yale-Princeton Football Game show the influence of college on Ives' composition. He wrote his Symphony No. 1 as his senior thesis under Parker's supervision.[1]

In 1898, after his graduation from Yale, he accepted a position as an actuarial clerk at Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York that paid $5 weekly, and moved into a bachelor apartment in New York shared with several other men. He continued his work as a church organist until as late as 1906. In 1899 he moved to employment with the agency Charles H. Raymond & Co., where he stayed until 1906. In 1907, upon the failure of Raymond & Co., he and his friend Julian W. Myrick formed their own insurance agency called Ives & Co., which later became Ives & Myrick, where he remained until he retired. In his spare time he composed music and, until his marriage, worked as an organist in Danbury and New Haven, Connecticut as well as Bloomfield, New Jersey and New York City.[1] In 1907, Ives suffered the first of several "heart attacks" (as he and his family called them) that he had through out his lifetime. These attacks may have been psychological in origin rather than physical. Following his recovery from the 1907 attack, Ives entered into one of the most creative periods of his life as a composer.

After marrying Harmony Twitchell in 1908, they moved into their own apartment in New York. He had a remarkably successful career in insurance, and continued to be a prolific composer until he suffered another of several heart attacks in 1918, after which he composed very little, writing his very last piece, the song Sunrise in August 1926. In 1922, Ives published his 114 Songs which represents the breadth of his work as a composer. It includes art songs, songs he wrote as a teenager and young man, and highly dissonant songs such as "The Majority."[1]

According to his wife, one day in early 1927 he came downstairs with tears in his eyes: he could compose no more, he said, "nothing sounds right." There have been numerous theories advanced to explain the silence of his late years, which seems as mysterious as the last several decades of the life of Jean Sibelius, who also stopped composing at almost the same time. While Ives had stopped composing, and was increasingly plagued by health problems, he did continue to revise and refine his earlier work, as well as oversee premieres of his music. After continuing health problems, including diabetes, he retired from his insurance business in 1930, which gave him more time to devote to his musical work, but he was unable to write any new music. During the 1940s he revised his Concord Sonata, publishing it and the accompanying prose volume, Essays Before a Sonata in 1947.[1]

Ives died in 1954 in New York City.

Ives' early music

Ives was trained at Yale, and his First Symphony shows a grasp of the academic skills required to write in the Sonata Form of the late nineteenth century, as well as an iconoclastic streak, with a second theme that implies different harmonic direction. His father was a band leader, and as with Hector Berlioz, Ives had a fascination with outdoor music and with instrumentation. His attempts to fuse these two musical pillars, and his devotion to Beethoven, would set the direction for his musical life.

Ives published a large collection of his songs, many of which had piano parts which echoed modern movements begun in Europe, including bitonality and pantonality. He was an accomplished pianist, capable of improvising in a variety of styles, including those which were then quite new. Although he is now best known for his orchestral music, he composed two string quartets and other works of chamber music. His work as an organist led him to write Variations on "America" in 1891, which he premiered at a recital celebrating the United States Declaration of Independence on the Fourth of July. The piece takes the tune (which is the same one as is used for the national anthem of the United Kingdom) through a series of fairly standard but witty variations. One of the variations is in the style of a polonaise while another, added some years after the piece had originally been composed, is probably Ives' first use of bitonality. William Schuman arranged this for orchestra in 1964.

Around the turn of twentieth century Ives was composing his 2nd Symphony which would begin a departure from the conservative teachings of Horatio Parker, his composition professor at Yale. His 1st symphony (composed while at Yale) was not unconventional since Parker had insisted he stick to the older European style. However the 2nd symphony (composed after he graduated) would include such new techniques as musical quotes, unusual phrasing and orchestration, and even a blatantly dissonant 11 note chord ending the work. The 2nd would foreshadow his later compositional style even though the piece is relatively conservative by Ives' standards.

In 1906 Ives would compose what some would argue would be the 1st radical musical work of the twentieth century, "Central Park in the Dark." The piece simulates an evening comparing sounds from nearby nightclubs in Manhattan (playing the popular music of the day, ragtime, quoting "Hello My Baby") with the mysterious dark and misty qualities of the Central Park woods (played by the strings). The string harmony uses shifting chord structures that, for the first time in musical history, are not solely based on thirds but a combination of thirds, fourths, and fifths. Near the end of the piece the remainder of the orchestra builds up to a grand chaos ending on a dissonant chord, leaving the string section to end the piece save for a brief violin duo superimposed over the unusual chord structures.

Ives had composed two symphonies, but it is with The Unanswered Question (1908), written for the highly unusual combination of trumpet, four flutes, and string quartet, that he established the mature sonic world which would be his signature style. The strings (located offstage) play very slow, chorale-like music throughout the piece while on several occasions the trumpet (positioned behind the audience) plays a short motif that Ives described as "the eternal question of existence." Each time the trumpet is answered with increasingly shrill outbursts from the flutes (onstage) creating The Unanswered Question. The piece is typical Ives; it juxtaposes various disparate elements and appears to be driven by a narrative that we are never made fully aware of, which creates a mysterious ambience. He later made an orchestral version that became one of his more popular works.[1]

Mature Period from 1910-1920

Starting around 1910, Ives would begin composing his most accomplished works including the "Holidays Symphony" and arguably his most well known piece, "Three Places in New England." Ives' mature works of this era would eventually compare with the two other great musical innovators at the time (Schoenberg and Stravinsky) making the case that Ives was the 3rd great innovator of early twentieth century composition. No less of an authority than Arnold Schoenberg himself would compose a brief poem near the end of his life honoring Ives' greatness as a composer.

Pieces such as The Unanswered Question were almost certainly influenced by the New England transcendentalist writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.[1] They were important influences to Ives, as he acknowledged in his Piano Sonata No. 2: Concord, Mass., 1840–60 (1909–1915), which he described as an:

impression of the spirit of transcendentalism that is associated in the minds of many with Concord, Massachusetts of over a half century ago. This is undertaken in impressionistic pictures of Emerson and Thoreau, a sketch of the Alcotts, and a scherzo supposed to reflect a lighter quality which is often found in the fantastic side of Hawthorne.[2]

The sonata is possibly Ives' best-known piece for solo piano (although it should be noted that there are optional parts for viola and flute). Rhythmically and harmonically, it is typically adventurous, and it demonstrates Ives' fondness for quotation.[3] For example, on several occasions the opening motto from Ludwig van Beethoven's Fifth Symphony is quoted. It also contains one of the most striking examples of Ives' experimentalism; in the second movement, he instructs the pianist to use a 14 3⁄4 in (37 cm) piece of wood to create a massive "cluster chord."

Perhaps the most remarkable piece of orchestral music Ives completed was his Symphony No. 4 (1910–1916). The list of forces required to perform the work alone is extraordinary. The work closely mirrors The Unanswered Question. There is no shortage of novel effects. A tremolo or tremolando is heard throughout the second movement. A fight between discordance and traditional tonal music is heard in the final movement. The piece ends quietly with just the percussion playing. A complete performance was not given until 1965, almost half a century after the symphony was completed, and years after Ives' death.

Ives left behind material for an unfinished Universe Symphony, which he was unable to assemble in his lifetime despite two decades of work. This was due to his health problems as well as his shifting conception of the work. There have been several attempts towards a completion of a performing version. However, none has found its way into general performance.[1] The symphony takes the ideas in the Symphony No. 4 to an even higher level, with complex cross rhythms and a difficult layered dissonance along with unusual instrumental combinations.

Ives' chamber works include the String Quartet No. 2, where the parts are often written at extremes of counterpoint, ranging from spiky dissonance in the movement labelled "Arguments" to transcendentally slow. This range of extremes is frequent in Ives' music with a crushing blare and dissonance contrasted with lyrical quiet. This is then carried out by the relationship of the parts slipping in and out of phase with each other. Ives' idiom, like Gustav Mahler's, employed highly independent melodic lines. It is regarded as difficult to play because many of the typical signposts for performers are not present. This work had a clear influence on Elliott Carter's Second String Quartet, which is similarly a four-way theatrical conversation.

Reception

Ives' music was largely ignored during his life, and many of his works went unperformed for many years. His tendency to experimentation and his increasing use of dissonance were not well taken by the musical establishment of the time. The difficulties in performing the rhythmic complexities in his major orchestral works made them daunting challenges even decades after they were composed. One of the more damning words one could use to describe music in Ives' view was "nice," and his famous remark "use your ears like men!" seemed to indicate that he did not care about his reception. On the contrary, Ives was interested in popular reception, but on his own terms.

Early supporters of his music included Henry Cowell and Elliott Carter. Invited by Cowell to participate in his periodical New Music, a substantial number of Ives' scores were published in the journal, but for almost 40 years he had few performances that he did not arrange or back, generally with Nicolas Slonimsky as the conductor.

His obscurity began to lift a little in the 1940s, when he met Lou Harrison, a fan of his music who began to edit and promote it. Most notably, Harrison conducted the premiere of the Symphony No. 3 (1904) in 1946. The next year, this piece won Ives the Pulitzer Prize for Music. However, Ives gave the prize money away (half of it to Harrison), saying "prizes are for boys, and I'm all grown up." Leopold Stokowski took on the Symphony No. 4 not long thereafter, regarding the work as "the heart of the Ives problem."[1]

At this time, Ives was also promoted by Bernard Herrmann, who worked as a conductor at CBS and in 1940 became principal conductor of the CBS Symphony Orchestra. While there he was a champion of Charles Ives' music.

Recognition of Ives' music has improved. He would find praise from Arnold Schoenberg, who regarded him as a monument to artistic integrity, and from the New York School of William Schuman. Michael Tilson Thomas is an enthusiastic exponent of Ives' symphonies as is musicologist Jan Swafford. Ives' work is regularly programmed in Europe. Ives has also inspired pictorial artists, notably Eduardo Paolozzi who entitled one of his 1970s suites of prints Calcium Light Night, each print being named for an Ives piece, (including Central Park in the Dark).

At the same time Ives is not without his critics. Many people still find his music bombastic and pompous. Others find it, strangely enough, timid in that the fundamental sound of European traditional music is still present in his works. His onetime supporter Elliot Carter has called his work incomplete.

Influence on twentieth-century music

Ives was a great supporter of twentieth century music. This he did in secret, telling his beneficiaries it was really Mrs. Ives who wanted him to do so. Nicolas Slonimsky, whose Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns influenced not only avant garde classical composers but also jazz improvisers John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Pharaoh Sanders, and their colleagues in the 1950s, introduced many new works from the podium. Slonimsky said of Ives in 1971, "He financed my entire career."[4]

List of selected works

Note: Because Ives often made several different versions of the same piece, and because his work was generally ignored during his lifetime, it is often difficult to put exact dates on his compositions. The dates given here are sometimes best guesses. There have even been speculations that Ives purposely misdated his own pieces earlier or later than actually written.

- Variations on America for organ (1891)

- String Quartet No. 1, From the Salvation Army (1896)

- Symphony No. 1 in D minor (1896–98)

- Symphony No. 2 (1897–1901)

- Symphony No. 3, The Camp Meeting (1901–04)

- Central Park in the Dark for chamber orchestra (1898–1907)

- The Unanswered Question for chamber group (1908)

- Violin Sonata No. 1 (1903–08)

- Piano Sonata No. 1 (1902–09)

- Violin Sonata No. 2 (1902–10)

- Robert Browning Overture (1911)

- A Symphony: New England Holidays (1904–13)

- String Quartet No. 2 (1907–13)

- Piano Trio (c1909–10, rev. c1914–15)

- Three Places in New England (Orchestral Set No. 1) (1903–21)

- Violin Sonata No. 3 (1914)

- Piano Sonata No. 2, Concord, Mass., 1840–60 (1909–15) (revised many times by Ives)

- Orchestral Set No. 2 (1912–15)

- Violin Sonata No. 4, Children's Day at the Camp Meeting (1912–15)

- Symphony No. 4 (1910–16)

- Universe symphony (uncompleted, 1911–16, worked on symphony until his death in 1954)

- 114 Songs (composed various years 1887–1921, published 1922.)

- Three Quarter Tone Piano Pieces (1923–24)

- Old Home Days (for wind band/ensemble, arranged by Jonathan Elkus)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Stanley Sadie, (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Grove's Dictionaries of Music Inc., 1995, ISBN 978-1561591749).

- ↑ Charles Ives, Howard Boatright (ed.), Essays Before a Sonata, The Majority, and Other Writings (W. W. Norton & Company, 1999, ISBN 978-0393318302).

- ↑ J. Peter Burkholder, All Made of Tunes: Charles Ives and the Uses of Musical Borrowing (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1995, ISBN 0300056427).

- ↑ Nicolas Slonimsky, Nicolas Slonimsky Eats Dinner, a dinner conversation about New Music and classical masters, 1971. Internet Archive. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Block, Geoffrey. Charles Ives: A Bio-bibliography. New York: Greenwood Press, 1988. ISBN 0313254044

- Burkholder, J. Peter. All Made of Tunes: Charles Ives and the Uses of Musical Borrowing. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1995. ISBN 0300056427

- Burkholder, J. Peter (ed). Charles Ives and His World. Princeton University Press: 1996. ISBN 0691011648

- Cowell, Henry, and Sidney Cowell. Charles Ives and His Music. Oxford University Press, 1955. ISBN 978-0195005189

- Ives, Charles, Howard Boatright (ed.). Essays Before a Sonata, The Majority, and Other Writings. W. W. Norton & Company, 1999. ISBN 978-0393318302

- Kirkpatrick, John (editor) Charles E. Ives: Memos. Calder & Boyars: 1973. ISBN 039302153X

- Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Grove's Dictionaries of Music Inc., 1995. ISBN 978-1561591749

- Sinclair, James B. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Music of Charles Ives. Yale University Press: 1999. ISBN 0300076010

- Swafford, Jan. Charles Ives: A Life with Music. New York: W. W. Norton, 1996. ISBN 978-0393038934

External links

All links retrieved December 4, 2023.

- The Charles Ives Society

- Ives Concert Park

- Charles Edward Ives Find A Grave.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.