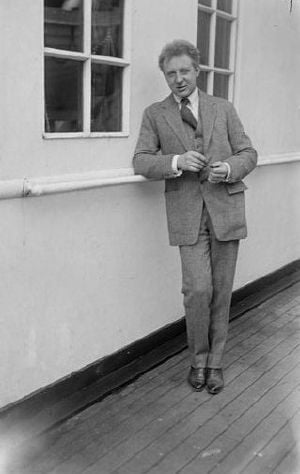

Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Stokowski (April 18, 1882 - September 13, 1977) (born Antoni Stanisław Bolesławowicz) was the conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, the Philadelphia Orchestra, the NBC Symphony Orchestra and the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra. He was the founder of the New York City Symphony Orchestra. He arranged the music for and appeared in Disney’s Fantasia.

Stokowski was the first symphonic conductor to achieve the status of a "superstar." In certain circles he was thought to be a shameless exhibitionist with an inflated ego and without the proper cultural background. Yet, it is undeniable that his personality and ebullient magnetism helped to make the modern symphony orchestra in America more mainstream in the country's musical life. His advocacy of new music was rivaled only by Koussevitsky in Boston, and this remains an important aspect of his musical legacy.

Like Koussevitsky, he utilized his creative energies and influence to mentor young musicians in the art Western music by establishing youth orchestra programs in several major American cities. In doing so, he displayed a deeply altrusitic attitude with regard to investing into the culture development of the comminities in which he lived and worked. His motivation to educate young people in the art of orchestral playing is also an important aspect of his legacy, reflecting a desire to give of himself in service of his art and his society.

Early Life

The son of Polish cabinetmaker Kopernik Józef Bolesław Stokowski and his Irish wife Annie Marion Moore, Stokowski was born in London, England, in 1882. There is a certain amount of mystery surrounding his early life. For example, no one could ever determine where his slightly Eastern European, foreign-sounding accent came from as he was a born and raised in London (it is surmised that this was a affectation on his part to add mystery and interest) and he also, on occasion, quoted his birth year as 1887 instead of 1882.

Stokowski trained at the Royal College of Music (which he entered in 1896, at the age of 13, one of the college's youngest students ever). He sang in the choir of St. Marylebone Church and later became Assistant Organist to Sir Henry Walford Davies at The Temple Church. At the age of 16, he was elected to membership in the Royal College of Organists. In 1900, he formed the choir of St. Mary's Church, Charing Cross Road. There, he trained the choirboys and played the organ, and in 1902 was appointed organist and choir director of St. James's Church, Piccadilly. He also attended Queen's College, Oxford where he earned a Bachelor of Music degree in 1903.

Personal Life

Stokowski married three times. His first wife was Lucie Hickenlooper (a.k.a. Olga Samaroff, former wife of Boris Loutzky), a Texas-born concert pianist and musicologist, to whom he was married from 1911 until 1923 (one daughter: Sonia Stokowski, an actress). His second wife was Johnson & Johnson heiress Evangeline Love Brewster Johnson, an artist and aviator, to whom he was married from 1926 until 1937 (two children: Gloria Luba Stokowski and Andrea Sadja Stokowski). His third wife, from 1945 until 1955, was railroad heiress Gloria Vanderbilt (born 1924), an artist and fashion designer (two sons, Leopold Stanislaus Stokowski b. 1950 and Christopher Stokowski b. 1955). He also had a much-publicized affair with Greta Garbo in 1937-1938.

Leopold Stokowski returned to England in 1972 and died there in 1977 in Nether Wallop, Hampshire at the age of 95.

Professional Career

In 1905, Stokowski began work in New York City as the organist and choir director of St. Bartholomew's Church. He became very popular amongst the parishoners (who included J. P. Morgan and members of the Vanderbilt family but eventually quit the position to pursue a post as an orchestra conductor. He moved to Paris for additional study before hearing that the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra would be needing a new conductor when it returned from a hiatus. So, in 1908, he began his campaign to obtain the position, writing multiple letters to the orchestra's president, Mrs. C. R. Holmes, and traveling to Cincinnati for a personal interview. Eventually, he was granted the post and officially took up his duties in the fall of 1909.

Stokowski was a great success in Cincinnati, introducing the idea of "pop concerts" and conducting the United States premieres of new works by composers such as Edward Elgar. However, in early 1912, he became sufficiently frustrated with the politics of the orchestra's board that he tendered his resignation. There was a dispute over the resignation, but on April 12 it was finally accepted.

Two months later, Stokowski was appointed director of the Philadelphia Orchestra and made his Philadelphia debut on October 11, 1912. His tenure in Philadelphia (1912-1936) would bring him some of his greatest accomplishments and recognition. He conducted the first American performances of important works including the monumental Eighth Symphony of Gustav Mahler, Alban Berg's Wozzeck and Stravinsky's Rite of Spring with the Philadelphians. Though his initial impact in Philadelphia was rather calm and without incident, it wasn't long before his flamboyancy and flair for the dramatic would emerge.

Stokowski rapidly garnered a reputation as a showman. His flair for the theatrical included grand gestures such as throwing the sheet music on the floor to show he did not need to conduct from a score. He also experimented with lighting techniques in the concert hall, at one point conducting in a dark hall with only his head and hands lighted, at other times arranging the lights so they would cast theatrical shadows of his head and hands. Late in the 1929-1930 season, he started conducting without a baton; his free-hand manner of conducting became one of his trademarks.

Stokowski's repertoire was broad and included contemporary works by composers such as Paul Hindemith, Arnold Schoenberg, Henry Cowell, and Edgard Varese. In 1933, he started "Youth Concerts" for younger audiences which are still a Philadelphia tradition.

After disputes with the board, Stokowski began to withdraw from involvement in the Philadelphia Orchestra from 1935 onward, allowing then co-conductor Eugene Ormandy to gradually succeed him as the orchestra's music director.

Following his tenure in Philadelphia, Leopold Stokowski directed several other ensembles, including the All-American Youth Orchestra (which he founded in 1940) the NBC Symphony Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic (both as co-conductor), the Houston Symphony Orchestra (1955-1961), and the American Symphony Orchestra, which he organized in 1962. He continued to make concert appearances and studio recordings of both standard works and unusual repertoire (including the first performance and recording of Charles Ives' decades-old Symphony No. 4) well into his 90s. He made his last public appearance as conductor in Venice in 1975, remaining active in the recording studio through 1977.

In 1944, on the recommendation of Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, Stokowski helped form the New York City Symphony Orchestra, aimed at middle-class workers. Ticket prices were set low, and the times of concerts made it convenient to attend after work. Many early concerts were standing room only. However, a year later in 1945, Stokowski was at odds with the board (who wanted to trim expenses even further) and he resigned.

In 1945, Stokowski founded the Hollywood Bowl Symphony. The orchestra lasted for two years before it was disbanded; though, it was later restarted in 1991. From 1955 to 1961, Stokowski was the Music Director of the Houston Symphony Orchestra.

In 1962, at the age of 80, Stokowski founded the American Symphony Orchestra. He served as music director for the orchestra, which continues to perform, until May 1972 when, at the age of 90, he returned to England.

In 1976, he signed a recording contract that would have kept him active until he was 100-years-old. However, he died of a heart attack the following year at the age of 95.

Legacy

Indeed, Leopold Stokowski was the first conductor to attain the status of a superstar. He was regarded as something of a matinee idol, an image aided by his appearances in such films as the Deanna Durbin spectacle One Hundred Men and a Girl (1937) and, most famously, as the flesh-and-blood leader of the Philadelphia Orchestra in Walt Disney's animated classic Fantasia (1940). In one memorable instance, he appears to be talking to the cartoon figure of Mickey Mouse, the "star" of a sequence featuring Dukas' The Sorcerer's Apprentice. In a clever parody, when the slumbering apprentice dreams of himself directing the forces of Nature with the masterful sweep of his hands, Disney artists copied Stokowski's own conducting gestures.

On the musical side, Stokowski nurtured the orchestra and shaped the "Stokowski" sound. He encouraged "free bowing" from the string section, "free breathing" from the brass section, and continually played with the seating arrangements of the sections as well as the acoustics of the hall in order to create better sound. His orchestral transcriptions of Johann Sebastian Bach's were written in the Philadelphia years as he began to "Stokowski-ize" the musical scene in Philadelphia.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Prokofiev, Sergey, Sterling Holloway, and Leopold Stokowski. Walt Disney presents "Peter and the Wolf" from Walt Disney's Fantasia/Paul Dukas. U.S.: Disneyland, 1969. OCLC 42570122

- Schonberg, Harold C. The Great Conductors. NY: Simon and Schuster, 1967. ISBN 6712073500

- Thomson, Virgil, and Leopold Stokowski. The plow that broke the plains: The river/suite/Igor Stravinsky. NY: Vanguard classics, 1991. OCLC 26980664

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.