Austria

| Republik Österreich Republic of Austria | |||||

| |||||

| Anthem: Land der Berge, Land am Strome (German) Land of Mountains, Land by the River | |||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Vienna 48°12′N 16°21′E | ||||

| Official languages | German | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic groups | Austrian 80.8% German 2.6% Bosnian and Herzegovinian 1.9% Turkish 1.8% Serbian 1.6% Romanian 1.3% other 10%[1] | ||||

| Government | Federal Parliamentary republic | ||||

| - President | Alexander Van der Bellen | ||||

| - Chancellor | Karl Nehammer | ||||

| - Vice Chancellor | Werner Kogler | ||||

| Independence | |||||

| - Austrian State Treaty in force | 27 July 1955 (Duchy: 1156, Austrian Empire: 1804, First Austrian Republic: 1918–1938, Second Republic since 1945) | ||||

| Accession to EU | 1 January 1995 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| - Total | 83,855 km² (115th) 32,377 sq mi | ||||

| - Water (%) | 1.7 | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - 2021 estimate | 8,884,864[1] | ||||

| - Density | 106/km² 274.5/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $461.432 billion[2] | ||||

| - Per capita | $51,936[2] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $446,315 billion[2] | ||||

| - Per capita | $50,277[2] | ||||

| HDI (2019) | 0.922 | ||||

| Currency | Euro (€) ² (EUR)

| ||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+01) | ||||

| - Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+02) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .at ³ | ||||

| Calling code | +43 | ||||

Austria (German: Österreich), officially the Republic of Austria (German: Republik Österreich), is a small, predominantly mountainous country located in Central Europe, approximately between Germany, Italy and Hungary.

The origins of modern Austria date back to the ninth century, when the countryside of upper and lower Austria became increasingly populated.

Since the Austrian ruling Habsburg dynasty controlled large parts of Western Europe for much of the period from 1278 to 1918, Austria has had a huge impact on the development of Western Europe.

After hundreds of years' involvement in innumerable wars, Austria is one of six European countries that have declared permanent neutrality and one of the few countries that includes the concept of everlasting neutrality in their constitution.

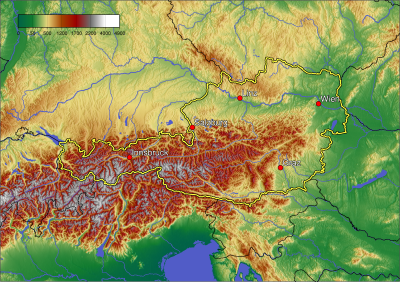

Geography

The German name Österreich can be translated into English as the "eastern realm," which is derived from the Old German Ostarrîchi. The name "Ostarrichi" is first documented in an official document from 996. Since then this word has developed into the German word Österreich. The name was Latinized as "Austria."

The landlocked country shares national borders with Switzerland and the tiny principality of Liechtenstein to the west, Germany and the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the north, Hungary to the east, and Slovenia and Italy to the south. It has a total area of 32,383 square miles (83,859 square kilometers), about twice the size of Switzerland and slightly smaller than the state of Maine in the U.S..

Austria may be divided into three unequal geographical areas. The largest part of Austria (62 percent) is occupied by the relatively young mountains of the Alps, but in the east, these give way to a part of the Pannonian plain, and north of the River Danube lies the Böhmerwald, an older, but lower, granite mountain range. The highest point is Grossglockner at 12,460 feet (3798 meters).

The greater part of Austria lies in the cool/temperate climate zone in which humid westerly winds predominate. The wetter western regions have an Atlantic climate with a yearly rainfall of about 40 inches (1000 millimeters), while the eastern regions have a drier, more continental type of climate, and less precipitation.

With over half of the country dominated by the Alps, the alpine climate predominates. In the east, in the Pannonian Plain and along the Danube valley, the climate shows continental features with less rain than the alpine areas. Although Austria is cold in the winter, in the summer temperatures can be relatively warm reaching 68°F -95°F (20°C-35°C).

Northern Austria is the location of the main watershed between the Black Sea and the North Sea. Most Austrian territory drains to the Danube River. Austria has numerous lakes, many a legacy of glacial erosion. The largest lakes are Lake Constance (Bodensee) in the west and the marshy Neusiedler Lake (Neusiedlersee) to the east.

Natural resources include oil, coal, lignite, timber, iron ore, copper, zinc, antimony, magnesite, tungsten, graphite, salt, and hydropower.

Austria has 44 percent of its area under forests. Deciduous beech, birch, and oak and conifers (fir) cover the mountains up to about 4000 feet (1200 meters), above which fir predominates and then gives way to larch and stone pine. Wildlife include some chamois, deer, hare, fox, badger, marten, Alpine chough, grouse, marmot, partridge, and pheasant. Birds include purple heron, spoonbill, and avocet. The ibex, once threatened, has begun breeding again.

Natural hazards include landslides, avalanches, and earthquakes. Environmental issues include some forest degradation caused by air and soil pollution, soil pollution resulting from the use of agricultural chemicals, air pollution resulting from emissions by coal- and oil-fired power stations and industrial plants and from trucks transiting Austria between northern and southern Europe.

Vienna is Austria's primary city, and had a population of about 1.7 million (2.3 million within the metropolitan area) in 2007. It is by far the largest city in Austria as well as its cultural, economic and political center.

History

Pre-history

The first traces of human settlement in the lands that became Austria date from the Lower Paleolithic Period (early Stone Age), about 2.5 million years ago. The archaeological evidence shows several distinct cultures either succeeded one another or coexisted. Hallstatt in Austria gave its name to a culture that lasted from 1200 B.C.E. to 500 B.C.E. The community at Hallstatt exploited the salt mines in the area. Hallstatt cemeteries contained weapons and ornaments from the Bronze Age, up to the fully developed Iron Age.

Noricum

Noricum was a Celtic federation of 12 tribes stretching over the area of today's Austria and Slovenia, and in the past a province of the Roman Empire. It was bounded on the north by the Danube, on the west by Raetia and Vindelicia, on the east by Pannonia, on the south by Italia and Dalmatia. The original population appears to have consisted of Pannonians (a people kin to the Illyrians), who after the great emigration of the Gauls became subordinate to various Celtic tribes. The country proved rich in iron and supplied material for the manufacturing of arms in Pannonia, Moesia and northern Italy. The famous Noric steel was largely used in the making of Roman weapons.

Roman rule

For a long time the Noricans enjoyed independence under princes of their own and carried on commerce with the Romans, until Noricum was incorporated into the Roman Empire in 16 B.C.E. The Romans built roads, and towns including Carnuntum (near Hainburg), and Vindobona (Vienna). Roman municipalities developed at Brigantium (Bregenz), Juvavum (Salzburg), Ovilava (Wels), Virunum (near Klagenfurt), Teurnia (near Spittal an der Drau), and Flavia Solva (near Leibnitz). Invasions of Germanic tribes in from 166 C.E. to 180 C.E. interrupted peaceful development. The Alemanni invaded in the third century. Under Diocletian (245-313), Noricum was divided into Noricum ripense ("Riverside Noricum," the northern part southward from the Danube) and Noricum mediterraneum. Subsequent attacks by Huns and eastern Germans overcame Roman provincial defenses in the area.

Severinus of Noricum

Severinus of Noricum (ca. 410-482), a Roman Catholic saint, was first recorded as traveling along the Danube in Noricum and Bavaria, preaching Christianity, procuring supplies for the starving, redeeming captives, and establishing monasteries at Passau and Favianae, and hospices in the chaotic territories that were ravaged by the Great Migrations, sleeping on sackcloth and fasting severely. His efforts seem to have won him wide respect, including that of the Hun chieftain Odoacer (435–493). His biographer Eugippius credits him with the prediction that Odoacer would become king of Rome.

Rupert of Salzburg

Rupert of Salzburg (660-710), was a Frank and bishop of Worms until around 697, when he was sent to become a missionary to Regensburg in Bavaria. He soon had converted a large area of the Danube, and introduced education and other reforms. He promoted the salt mines of Salzburg, then a ruined Roman town of Juvavum, and made it his base and renamed the place "Salzburg."

Germanic, Slavic settlement

During the Migration Period (300-700), the Slavs migrated into the Alps in the wake of the expansion of their Avar overlords during the seventh century, mixed with the Celto-Romanic population, and established the realm of Karantania, which covered much of eastern and central Austrian territory, and lasted almost 300 years. In the meantime, the Germanic tribe of the Bavarians had developed in the fifth and sixth century in the west of the country and in Bavaria, while what is today Vorarlberg had been settled by the Alemans. Those groups mixed with the Rhaeto-Romanic population and pushed it up into the mountains.

Karantania, under pressure of the Avars, lost its independence to Bavaria in 745 and became a margraviate, which was a medieval border province. During the following centuries, Bavarian settlers went down the Danube and up the Alps, a process through which Austria was to become the mostly German-speaking country it is today. The Bavarians themselves came under the overlordship of the Carolingian Franks and subsequently a Duchy of the Holy Roman Empire. Duke Tassilo III, who wanted to maintain Bavarian independence, was defeated and displaced by Charlemagne in 788. From 791 to 796, Charlemagne led a number of attacks against the Avars, making them resettle to the eastern part of lower Austria, where they were presumably assimilated into the local population.

March of Austria

Franks instituted border provinces known as marches, in newly won territory. The marches were overseen by a comes or dux as appointed by the warlord. The title was eventually regularized to margravei (German: markgraf). (i.e. "count of the mark"). The first march, covering approximately the territory that would become Austria, was the Eastern March (marchia orientalis), established by Charlemagne in the late eighth century against the Avars. When the Avars disappeared in the 820s, they were replaced largely by a Slavic people, who established the state of Great Moravia. The region of Pannonia was set apart from the Duchy of Friuli in 828 and set up as a march against Moravia within the regnum of Bavaria. These marches corresponded to a frontier along the Danube from the Traungau to Szombathely and the Raba river and including the Vienna basin.

Magyar incursions began in 881. By the 890s, the Pannonian march seems to have disappeared. By 906, Magyars had destroyed Great Moravia, and in 907, the Magyars defeated a large Bavarian army near Pressburg (Bratislava). But Emperor Otto the Great (912-973) defeated the Magyars in the Battle of Lechfeld (955). The marchia orientalis, that was to become the core territory of Austria, was given to Leopold of Babenberg (d. 994) in 976 after the revolt of Henry II, Duke of Bavaria.

The first record showing the name Austria is 996 were it is written as Ostarrîchi, referring to the territory of the Babenberg March. The term Ostmark is not historically ascertained and appears to be a translation of marchia orientals that came up only much later.

Babenberg Austria

Originally from Bamberg in Franconia, now northern Bavaria, an apparent branch of the Babenbergs went on to rule Austria as counts of the march and dukes from 976 to 1248, before the rise of the house of Habsburg. Those centuries were characterized by settlement, forest clearing, establishment of towns and monasteries, and expansion. Leopold I (d.994) extended the eastern frontier to the Vienna Woods after a war with the Magyars. Henry I, who was margrave from 994 to 1018, controlled the country around Vienna and created new marches in what was later known as Carniola and Styria. Margrave Adalbert battled Hungarians and Moravians during his rule from 1018 to 1055. Austria was drawn into the Investiture Controversy, a struggle for control of the church in Germany, between Pope Gregory VII and King Henry IV from 1075.

Leopold III (1095–1136) married Holy Roman Emperor Henry V's sister Agnes, and during his rule, Austrian common law was first mentioned. On Leopold III's death, the Babenbergs were drawn into a conflict between the two leading German dynasties, the Hohenstaufen and the Welfs—on the side of the Hohenstaufen. In 1156, the Privilegium Minus elevated Austria to the status of a duchy. In 1192, the Babenbergs also acquired the Duchy of Styria through the Georgenberg Pact. At that time, the Babenberg dukes came to be one of the most influential ruling families in the region.

The reign of Leopold VI (1198-1230) was a time of great prosperity. He founded a Cistercian monastery at Lilienfeld (c. 1206), he participated in crusades, and brought about the Treaty of San Germano between Emperor Frederick II and Pope Gregory IX in 1230.

But his son Frederick II (1201-1246), known as "the Warlike" and "the Quarrelsome," was known for harsh internal policy, failed military excursions against neighboring lands, and opposition to the emperor Frederick II, which led in 1237 to the temporary loss of both Austria and Styria. On June 15, 1246, he was killed in battle against the Hungarians, and the male line of the family came to an end. This resulted in the interregnum, a period of several decades during which the status of the country was disputed.

The Babenberg era produced excellent Romanesque and early Gothic architecture, the court attracted leading German poets, and the Nibelung saga was written down.

Rise of The Habsburgs (1278-1526)

Austria came briefly under the rule of the Czech King Otakar II (1253–1278), who controlled the duchies of Austria, Styria and Carinthia. Contesting the election of Rudolf I of Habsburg (1218-1291) as emperor, Otakar was defeated and killed in the battle of Dürnkrut and Jedenspeigen in 1278 by the German King, who took Austria and gave it to his sons, Albert and Rudolf II, to govern in 1282. After opposition from the Austrians, the Treaty of Rheinfelden in 1283 provided that Duke Albert should be the sole ruler. Austria was ruled by the Habsburgs for the next 640 years.

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Habsburgs began to accumulate other provinces in the vicinity of the Duchy of Austria, which remained a small Duchy along the Danube, and Styria, which they had acquired from Ottokar alongside with Austria. Carinthia and Carniola came under Habsburg rule in 1335, Tyrol in 1363. These provinces, together, became known as the Habsburg hereditary lands, although they were sometimes all lumped together simply as Austria.

During his notable but short rule, Rudolf IV (1358-1365) proclaimed the indivisibility of Habsburg hereditary possessions, which corresponded roughly to the modern republic of Austria. He started to rebuild St Stephen's Cathedral in the Gothic style, and founded the University of Vienna (1365). Rudolf is best known for the forgery of the Privilegium Maius, which de facto put him on par with the Electors of the Holy Roman Empire, compensating for Austria's failure to receive an electoral vote in the Golden Bull. The title of archduke, invented by Rudolf, became an honorific title of all males of the House of Habsburg in the sixteenth century.

His brothers Albert III (1349-1395) and Leopold III (1351-1386) split the realms in the Treaty of Neuberg in 1379. Albert retained Austria proper, while Leopold took the remaining territories. In 1402, there was another split in the Leopoldinian line, when Ernest the Iron (1377-1424) took Inner Austria (Styria, Carinthia and Carniola) and Frederick IV (1382-1439) became ruler of Tyrol and Further Austria. The territories were only reunified by Ernest's son Frederick V (Frederick III as Holy Roman Emperor), when the Albertinian line (1457) and the Elder Tyrolean line (1490) had become extinct.

In 1396, representatives of nobility, monasteries, towns, and marketplaces were first assembled to consider the Turkish threat. From then, these estates or diets were to play an important political role in Austria. Sometimes peasants sent their representatives. Habsburg partitions, and periodic regencies, meant the assemblies gained in importance, and insisted on the right to levy taxes and duties.

In 1438, Duke Albert V of Austria was chosen as the successor to his father-in-law, Emperor Sigismund. Although Albert himself only reigned for a year, from then on, every emperor was a Habsburg, with only one exception. The Habsburgs began also to accumulate lands far from the Hereditary Lands. The reign of Frederick III (1415–1493) was characterized by strife with the estates, with his neighbors, and with his jealous family.

During the reign of Emperor Archduke Maximilian (1459–1519), the Habsburg empire became a great power, as its territory expanded because of several advantageous marriages. Maximilian married Mary of Burgundy, thus acquiring most of the Low Countries. His son Philip the Fair married Joanna, daughter of Ferdinand V and Isabella I, and thus acquired Spain and its Italian, African, and New World appendages. Philip’s son Ferdinand I married into the ruling House of Bohemia and Hungary and became King of Bohemia in 1524.

Empire combined and divided

Ferdinand’s brother Charles became Holy Roman Emperor as Charles V (1500–1558) after Maximilian died in 1519. Charles V combined under his rule Habsburg hereditary lands in Austria, the Low Countries, and Spain and its possessions—a huge territory which was impossible for one monarch to rule. In 1520, Emperor Charles V (1500–1558) left Habsburg hereditary territories in Austria and part of Germany to the rule of his brother, Ferdinand (1503–1564). The division of the Habsburg dynasty into Spanish and Austrian branches was finalized in 1556 when Charles abdicated as King of Spain in favor of his son Philip II and, in 1558, as Holy Roman Emperor in favor of his brother Ferdinand.

The Reformation

Austria and the other Habsburg hereditary provinces (and Hungary and Bohemia, as well) were much affected by the Reformation, the separation of Protestant denominations from the Catholic Church that started in 1517. Although the Habsburg rulers themselves remained Catholic, the provinces themselves largely converted to Lutheranism, which Ferdinand I and his successors, Maximilian II, Rudolf II, and Mathias largely tolerated. The nobility turned toward Lutheranism, while the peasants were attracted by the Anabaptists, who were persecuted. In 1528, Annabaptist leader Balthasar Hubmaier was burned at the stake in Vienna, and in 1536, Tirolean Anabaptist Jakob Hutter, was burned at the stake in Innsbruck. The Peace of Augsburg in 1555 brought some peace based on the principle that each ruler had the right to determine his religion and that of his subjects.

Counter-Reformation

In the late sixteenth century, however, the Counter-Reformation began to make its influence felt, and the Jesuit-educated Archduke Ferdinand (1529–1595) who ruled over Styria, Carinthia, and Carniola, was energetic in suppressing heresy in the provinces which he ruled. When, in 1619, he was elected emperor to succeed his cousin Mathias, Ferdinand II, as he became known, embarked on an energetic attempt to re-Catholicize not only the hereditary provinces, but Bohemia and Habsburg Hungary as well. The Protestants in Bohemia rebelled in 1618, thus beginning the first phase of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), which had greatly negative consequences for Habsburg control of the empire itself. These campaigns within the Habsburg hereditary lands were largely successful, leaving the emperors with much greater control within their hereditary power base, although Hungary was never successfully re-Catholicized.

Conflict with the Turks

Ferdinand’s defeat by the Ottoman Turks in the Battle of Mohács of 1526, in which Ferdinand's brother-in-law Louis II, King of Hungary and Bohemia, was killed, and the first siege of Vienna, which followed in 1529, initiated the Austrian phase of the Habsburg-Ottoman Wars. Ferdinand brought Bohemia and that part of Hungary not occupied by the Ottomans under his rule. Habsburg expansion into Hungary, however, led to frequent conflicts with the Turks, particularly the so-called Long War of 1593 to 1606. The long reign of Leopold I (1657-1705) saw the culmination of the Austrian conflict with the Turks. Following the successful defense of Vienna in 1683, a series of campaigns resulted in the return of all of Hungary to Austrian control by the Treaty of Carlowitz in 1699.

The War of the Spanish Succession

In 1700, the physically disabled, mentally retarded and disfigured Habsburg Charles II of Spain (1661-1700) died without an heir. He bequeathed Spain, the Spanish Netherlands, and possessions in Italy to Philip, Duke of Anjou, a grandson of Louis XIV, King of France. The Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, a Habsburg from the Austrian line, claimed these lands for his son Joseph I. This led to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714), in which the French and Austrians (along with their British and Dutch allies) fought over the inheritance of the vast territories of the Spanish Habsburgs. Although the French secured control of Spain and its colonies for Philip, the Austrians also ended up making significant gains in Western Europe, including the former Spanish Netherlands (now called the Austrian Netherlands, including most of modern Belgium), the Duchy of Milan in Northern Italy, and Naples and Sardinia in Southern Italy.

The Pragmatic Sanction and the War of the Austrian Succession

In 1713, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI (1711–1740), who had no living male heirs, promulgated the so-called Pragmatic Sanction, which declared his possessions indivisible and hereditary in both the male and female line—making his daughter Maria Theresa his heir. Most European monarchs accepted the Pragmatic Sanction in exchange for territory and authority. After Charles' death in 1740, Charles Albert (1697-1745), the prince-elector of Bavaria who was son-in-law of Joseph I, Holy Roman Emperor, rejected the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 and claimed the German territories of the Habsburg dynasty. He invaded Upper Austria in 1741, thus sparking the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), which began under the pretext that Maria Theresa of Austria was ineligible to succeed to the Habsburg throne, because Salic law precluded royal inheritance by a woman. The war featured a struggle of Prussia and the Habsburg monarchs for control of the economically important region of Silesia. Austria lost most of the economically developed Silesia to Prussia.

Enlightened despotism

In 1745, following the reign of the Bavarian Elector as Emperor Charles VII, Maria Theresa's husband Francis of Lorraine, Grand Duke of Tuscany, was elected emperor, restoring control of that position to the Habsburgs (or, rather, to the new composite house of Habsburg-Lorraine). Maria Theresa remained the power on the throne.

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763), which claimed between 900,000 and 1,400,000 people and involved all of the major European powers of the period. The war ended France's position as a major colonial power in the Americas, and its position as the leading power in Europe, until the time of the French Revolution. Great Britain, meanwhile, emerged as the dominant colonial power in the world. The war left Austria, exhausted, continuing the alliance with France (cemented in 1770 with the marriage of Maria Theresa's daughter Archduchess Maria Antonietta to the Dauphin), but also facing a dangerous situation in Central Europe, faced with the alliance of Frederick the Great of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia.

On Maria Theresa's death in 1780, she was succeeded by her son Joseph II, already Holy Roman Emperor since Francis I's death in 1765. Joseph was a reformer, and is often considered the foremost example of an eighteenth century enlightened despot. He abolished serfdom, improved civil and criminal procedures, decreed religious toleration and freedom of the press, and attempted to control the Roman Catholic Church and the various provincial nobilities. His reforms led to widespread resistance, especially in Hungary and the Austrian Netherlands, which were used to their traditional liberties. He pursued a policy of alliance with Catherine the Great's Russia, which led to a war with the Ottoman Empire in 1787. Austria's performance in the war was distinctly unimpressive, and the expense involved led to further resistance.

Joseph was succeeded by his more sensible brother, Leopold II, previously the reforming Grand Duke of Tuscany. Leopold knew when to cut his losses, and soon cut deals with the revolting Netherlanders and Hungarians. He revoked most of the reforms and recognized Hungary as a separate unit. He also managed to secure a peace with Turkey in 1791, and negotiated an alliance with Prussia, which had been allying with Poland to press for war on behalf of the Ottomans against Austria and Russia.

War with revolutionary France

From 1792 to 1815 the Habsburg Empire was at war, first with revolutionary France, and then in the Napoleonic Wars. Although Leopold was sympathetic to the revolutionaries, he was also the brother of the French queen. Disputes arose involving the rights of various imperial princes in Alsace, where the revolutionary French government was attempting to remove rights. Although Leopold did his best to avoid war with the French, he died in March of 1792. The French declared war on his inexperienced son Francis II a month later. An initially successful Austro-Prussian invasion of France faltered when the French forces drove the invaders back across the border and, during the winter of 1794-1795, conquered the Austrian Netherlands.

Defeats by Napoleon in 1797 and 1799 led to the Imperial Deputation Report of 1803, in which the Holy Roman Empire was reorganized, with nearly all of the ecclesiastical territories and free cities, traditionally the parts of the empire most friendly to the House of Austria, eliminated. With Bonaparte's assumption of the title of Emperor of the French in 1804, Francis, seeing the writing on the wall for the old Empire, took the new title of Emperor of Austria as Francis I, in addition to his title of Holy Roman Emperor. Defeat at Austerlitz on December 2, 1805, meant the end of the old Holy Roman Empire. Napoleon's satellite states in southern and Western Germany seceded from the empire in the summer of 1806, forming the Confederation of the Rhine, and a few days later Francis proclaimed the Empire dissolved, and renounced the old imperial crown.

Napoleon's fortunes eventually turned. He was defeated at Leipzig in October 1813, and abdicated on April 3, 1814. Louis XVIII was restored, soon negotiating a peace treaty with the victorious allies at Paris in June.

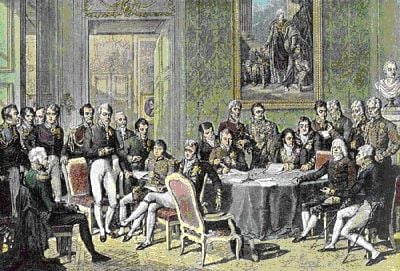

The Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference between ambassadors, from the major powers in Europe that was chaired by the Austrian chancellor Klemens Wenzel von Metternich (1773–1859) and held in Vienna, Austria, from November 1, 1814, to June 8, 1815. Its purpose was to settle issues and redraw the continent's political map after the defeat of Napoleonic France the previous spring, which would also reflect the change in status by the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire eight years before. The discussions continued despite the former emperor Napoleon I's return from exile and resumption of power in France in March 1815, and the Congress's Final Act was signed nine days before his final defeat at Waterloo on June 18, 1815.

Austria emerged from the Congress of Vienna as one of three of the continent's dominant powers (together with Russia and Prussia). Although Austria lost some territories in Belgium and south-west Germany, it gained Lombardy, Venetia, Istria, and Dalmatia. In 1815 the German Confederation, (German) Deutscher Bund was founded under the presidency of Austria, with Austria and Prussia the leading powers.

Revolutions of 1848

Under the control of Metternich, the Austrian Empire entered a period of censorship and a police state in the period between 1815 and 1848. The empire was basically rural, although industrial growth had taken place since the late 1820s. Unsolved social, political and national conflicts made the Habsburg Empire susceptible to the 1848 revolution, a revolutionary wave which erupted in Sicily and then, further triggered by the French Revolution of 1848, soon spread to the rest of Europe. From March 1848 through July 1849, much of the revolutionary activity was of a nationalist character. The empire, ruled from Vienna, included Austrian Germans, Hungarians, Slovenes, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Ruthenians, Romanians, Serbs, Italians, and Croats, all of whom attempted in the course of the revolution to either achieve autonomy, independence, or even hegemony over other nationalities. The nationalist picture was further complicated by the simultaneous events in the German states, which moved toward greater German national unity.

Metternich and the mentally handicapped Emperor Ferdinand I (1793-1875) were forced to resign to be replaced by his young nephew Franz Joseph (1830-1916). Separatist tendencies (especially in Lombardy and Hungary) were suppressed by military force. A constitution was enacted in March 1848, but it had little practical impact. However, one of the concessions to revolutionaries with a lasting impact was freeing of peasants in Austria. This facilitated industrialization, as many flocked to the newly industrializing cities of the Austrian domain. (Industrial centers were Bohemia, Lower Austria with Vienna, and Upper Styria). Social upheaval led to increased strife in ethnically mixed cities, leading to mass nationalist movements.

Austria-Hungary created

The defeat at Königgrätz in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 resulted in Austria's exclusion from Germany; the German Confederation was dissolved. The monarchy's weak external position forced Franz Joseph to concede also internal reforms. To appease Hungarian nationalism, Franz Joseph made a deal with Hungarian nobles, which led to the creation of Austria-Hungary through the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. The western half of the realm (Cisleithania) and Hungary (Transleithania) now became two realms with different interior policy, but with a common ruler and a common foreign and military policy.

The 1867 compromise heightened the desire for autonomy among other national groups within the empire, which was also home to Czechs, Poles, Ruthenes (Ukrainians), Slovaks, Serbs, Romanians, Croats, Slovenes, and Italians. About 6.5 million Czechs living in Bohemia, Moravia, and Austrian Silesia made up the largest, and most restless minority.

The Austrian half of the dual monarchy began to move towards constitutionalism. A constitutional system with a parliament, the Reichsrat was created, and a bill of rights was enacted also in 1867. Suffrage to the Reichstag's lower house was gradually expanded until 1907, when equal suffrage for all male citizens was introduced. However, the effectiveness of parliamentarism was hampered by conflicts between parties representing different ethnic groups, and meetings of the parliament were ceased altogether during World War I.

The decades until 1914 featured a lot of construction, expansion of cities and railway lines, and development of industry. During this period, now known as Gründerzeit, Austria became an industrialized country, even though the Alpine regions remained characterized by agriculture.

Alliance with Germany

Austrian foreign minister Gyula Andrássy (1823-1890), adopted a policy of friendship with the German Empire, which was founded in 1871. Andrássy said that Austria-Hungary would not interfere in German internal affairs, while Germany backed Austro-Hungarian attempts to limit Russian influence in south-eastern Europe. In 1878, Austria-Hungary occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had been cut off from the rest of the Ottoman Empire by the creation of new states in the Balkans. The territory was annexed in 1907 and put under joint rule by the governments of both Austria and Hungary. In 1879, Germany and Austria-Hungary signed a formal alliance, which, with the addition of Italy in 1882, became known as the Triple Alliance.

World War I

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (1863-1914), who was the presumed heir of Franz Joseph as Emperor, and his wife, in Sarajevo, in 1914 by Gavrilo Princip (a member of the Serbian nationalist group the Black Hand), was the proximate cause of World War I, a global military conflict which took place primarily in Europe from 1914 to 1918. After receiving assurances of support from Germany, the Austro-Hungarian foreign office held the Serbian government responsible, and issued an ultimatum. Despite a conciliatory reply, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28. Germany declared war on Russia and France in early August, sparking World War I. Over 40 million casualties resulted, including approximately 20 million military and civilian deaths. The Entente Powers, led by France, Russia, the British Empire, and later Italy (from 1915) and the United States (from 1917), defeated the Central Powers, led by the Austro-Hungarian, German, and Ottoman Empires.

Austro-Hungarian military initially fought Russia and Serbia. Italy, which had declared its neutrality, left the Triple Alliance and entered the war, in 1915, on the side of the Allies. The monarchy began to disintegrate, Emperor Franz Joseph I died in 1916, and was succeeded by his grand-nephew, Karl of Austria (1887-1922). In 1917, Emperor Karl failed to achieve a separate peace with the Allies, angering the Germans.

During early to mid 1918, Austro-Hungarian forces were defeated, while food shortages resulted in strikes and demonstrations at home, and mutinies in the military. Nationalist groups organized national councils. The Southern Slavs, meeting in October 1918, advocated union with Serbia, while Czechs proclaimed an independent republic in Prague. The Hungarian government separated from Austria on November 3, the day Austria and Hungary each signed an armistice with the Allies. On November 12, Emperor Karl went into exile. Between 1918 and 1919, Austria, with most of the German-speaking parts, was officially known as the Republic of German Austria (Republik Deutschösterreich). The monarchy was dissolved in 1919, and a parliamentary democracy was set up by the constitution of November 10, 1920.

The lnterwar years

The Austrian Republic started as a disorganized state of about seven million people, minus the industrial areas of Bohemia and Moravia, and without the large internal market created by the union with Hungary. The newly formed Austrian parliament asked for union with Germany, but the Treaty of Saint Germain prohibited political or economic union with Germany and forced the country to change its name from the "Republic of German Austria" to the "Republic of Austria," i.e. the First Republic. In 1920, the modern Constitution of Austria was enacted, creating a federal state, with a bicameral legislature and a democratic suffrage.

From 1919 to 1920, the United States, British, and Swedish organizations provided food. In the autumn of 1922, Austria was granted an international loan supervised by the League of Nations to avert bankruptcy, stabilize the currency, and improve the general economic condition. With the granting of the loan, Austria passed from an independent state to the control exercised by the League of Nations. At the time, the real ruler of Austria became the League, through its commissioner in Vienna. The commissioner was a Dutchman not formally part of the Austrian government. Austria pledged to remain independent for at least 20 years.

Austrian politics were characterized by intense and sometimes violent conflict between left and right from 1920 onwards. The Social Democratic Party of Austria, which pursued a fairly left-wing course known as Austromarxism at that time, could count on a secure majority in "Red Vienna," while right-wing parties controlled all other states. Since 1920, Austria was ruled by the Christian Socialist Party, which had close ties to the Roman Catholic Church. It was headed by a Catholic priest named Ignaz Seipel (1876-1932), who served twice as Chancellor. While in power, Seipel was working for an alliance between wealthy industrialists and the Roman Catholic Church.

Both left-wing and right-wing paramilitary forces were created during the 1920s, namely the Heimwehr in 1921-1923 and the Republican Schutzbund in 1923. A clash between those groups in Schattendorf, Burgenland, on January 30, 1927, led to the death of a man and a child. Right-wing veterans were indicted at a court in Vienna, but acquitted in a jury trial. This led to massive protests and fire at the Justizpalast in Vienna. In the July Revolt of 1927, 89 protesters were killed by the Austrian police forces. Political conflict escalated until the early 1930s. Engelbert Dollfuß (1892-1934) of the Christian Social Party became Chancellor in 1932.

Austrofascism and Anschluss

| Border of Austria-Hungary in 1914 |

| Borders in 1914 |

| Borders in 1920 |

The conservative Christian Social Party dominated a series of federal governments while unrest continued during the economic misery of the Great Depression. Austrian Nazism became a new destabilizing factor. Faced with growing opposition from the left and the extreme right, Dollfuss took advantage of a formal error during a vote in 1933 and dissolved parliament to rule by decree. On February 12, 1934, this new Austrofascist regime, backed by the army and the Heimwehr (Home Defence League), searched the headquarters of and banned the Socialist Party. Later Dollfuss abolished opposing political parties.

On May 1, 1934, the Dollfuss cabinet approved a new constitution that abolished freedom of the press, established one party system (known as "The Patriotic Front") and created a total state monopoly on employer-employee relations. This system remained in force until Austria became part of the Third Reich in 1938. The Patriotic Front government frustrated the ambitions of pro-Hitlerite sympathizers in Austria who wished both political influence and unification with Germany, leading to the assassination of Dollfuss on July 25, 1934, during an attempted Nazi takeover.

His successor Schuschnigg maintained the ban on pro-Hitlerite activities in Austria. A Rome-Berlin Axis was established in 1936. Schuschnigg reached an agreement with German leader Adolf Hitler that acknowledged Austria as “a German state.” When Schuschnigg called for a plebiscite on Austrian independence in 1938, Hitler demanded and received his resignation on March 11, 1938. The Anschluss (annexation) was accomplished when German troops occupied Austria on March 12, who met celebrating crowds. A Nazi government was formed, headed by Nazi puppet Arthur Seyss-Inquart (1892-1946) as Chancellor. A referendum on April 10 approved of the annexation with a majority of 99.73 percent. This referendum is, however, believed by many observers and historians to have been rigged. Austria, called the Ostmark (Eastern March) until 1942 when it was renamed Alpen-Donau-Reichsgaue, was divided into seven administrative districts under the authority of the German Third Reich.

World War II

World War II was a worldwide military conflict, which split the majority of the world's nations into two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis Powers. Spanning much of the globe, World War II resulted in the death of over 70 million people, making it the deadliest conflict in human history.

The annexation of Austria was enforced by military invasion but large parts of the Austrian population were in favor of the Nazi regime, many Austrians would participate in its crimes. There was a Jewish population of about 200,000 then living in Vienna, which had contributed considerably to science and culture and very many of these people, with socialist and Catholic Austrian politicians were deported to concentration camps, murdered or forced into exile.

In October 1943, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) signed the Moscow Declaration, which asserted the re-establishment of an independent Austria as an Allied war aim. Just before the end of the war, on March 28, 1945, American troops set foot on Austrian soil and the Soviet Union's Red Army crossed the eastern border two days later, taking Vienna on April 13. American and British forces occupied the western and southern regions, preventing Soviet forces from completely overrunning and controlling the country.

Just before the collapse of the Third Reich, the defeat of Germany and the end of the war, the Socialist leader Karl Renner (1870-1950), astutely set up a Provisional Government in Vienna in April 1945 with the tacit approval of the Soviet forces and declared Austria's secession from the Third Reich. Western occupation powers recognized Renner's provisional government in October, and parliamentary elections were held in November. The Austrian People’s Party won 85 of the National Assembly's 165 seats, the Socialists won 76 seats, and the Communists won four seats. Renner was elected president, and a coalition government with the People’s Party leader Leopold Figl (1902-1965) as Chancellor was formed.

Allied occupation

Austria, in general, was treated like it had been originally invaded by Germany and liberated by the Allies. The country was occupied by the Allies from May 9, 1945 and under the Allied Commission for Austria established by an agreement on July 4, 1945, it was divided into Zones occupied respectively by American, British, French and Soviet Army personnel, with Vienna being also divided similarly into four sectors - with an International Zone at its heart. Largely owing to Karl Renner's action on April 27th in setting up a Provisional Government, the Austrian Government had the right to legislate and to administer the laws. The occupation powers controlled demilitarization and the disposal of German-owned property—which was assigned to the respective occupying power in each zone.

The war had shattered Austrian industry, disrupted transport, and the people had suffered, especially from starvation. The UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) by mid-1947 averted the danger of starvation. Austria would benefit from the Marshall Plan but economic recovery was very slow - as a result of the State's ten-year political overseeing by the Allied Powers. By 1951 industrial production had exceeded pre-war peaks.

Independence

On May 15, 1955, Austria regained full independence by concluding the Austrian State Treaty with the Four Occupying Powers. The treaty prohibited unification of Austria and Germany, denied Austria the right to own or manufacture nuclear weapons or guided missiles, and obliged Austria to give the USSR part of its crude oil output. Negotiations for the treaty had begun in 1947. The main issue was the future of Germany. On October 26, 1955, Austria was declared "permanently neutral" by act of Parliament, which it remains to this day.

The Second Republic

Contrary to the First Republic, the Second Republic became a stable democracy. The two largest leading parties, the Christian-conservative Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) and the Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) remained in a coalition led by the ÖVP until 1966. The communists (KPÖ), who had hardly any support in the Austrian electorate, remained in the coalition until 1950 and in parliament until 1959. For much of the Second Republic, the only opposition party was the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), which included pan-German and liberal political currents. It was founded in 1955 as a successor organization to the short-lived Federation of Independents (VdU).

The political system of the Second Republic came to be characterized by the system of Proporz, meaning that most posts of some political importance were split evenly between members of the Social Democrats (Labour Party) and the People's Party (Conservatives). Interest group representations with mandatory membership (e.g. for workers, businesspeople, farmers etc.) grew to considerable importance and were usually consulted in the legislative process, so that hardly any legislation was passed that did not reflect widespread consensus. The Proporz and consensus systems largely held even during the years between 1966 and 1983, when there were non-coalition governments.

Renner died in December 1950 and was succeeded by the Socialist Party leader, Theodore Koerner. In 1957, Austria became involved in a dispute with Italy over the status of Austrians in the South Tirol, which had been under Italian rule since 1919. A settlement was reached in 1970. In 1960, Austria signed the pact establishing the European Free Trade Association.

Kreisky government

The Socialists, in March 1970, became the largest party in the National Assembly. Socialist leader Bruno Kreisky (1911-1990) was appointed chancellor and formed the first Austrian all-Socialist Cabinet, supported by the Freedom Party. The 1971 elections gave the Socialists an absolute majority, enabling them to govern alone. The Kreisky era brought modernization and a dramatic increase in the standard of living. Many social and labour reforms were introduced. In 1972, Austria signed a free trade agreement with the European Economic Community. He faced opposition on environmental issues, proposed tax increases, and especially the building of a nuclear power plant near Vienna, which the government was forced to abandon when it was nearly completed. Kreisky resigned in 1983, after the Socialists lost their majority. The 1970s were then seen as a time of liberal reforms in social policy. The economic policies of the Kreisky era have been criticized, as the accumulation of a large national debt began, and non-profitable nationalized industries were strongly subsidized.

From 1983

Following severe losses in the 1983 elections, the SPÖ entered into a coalition with the FPÖ under the leadership of Fred Sinowatz (b. 1929). In Spring 1986, Kurt Waldheim (1918-2007) was elected president amid considerable national and international protest because of his possible involvement with the Nazis and war crimes during World War II. Fred Sinowatz resigned, and Franz Vranitzky (b. 1937) became chancellor.

In September 1986, in a confrontation between the German-national and liberal wings, Jörg Haider became leader of the FPÖ. Chancellor Vranitzky rescinded the coalition pact between FPÖ and SPÖ, and after new elections, entered into a coalition with the ÖVP, which was then lead by Alois Mock. Jörg Haider's populism and criticism of the Proporz system allowed him to gradually expand his party's support in elections, rising from four percent in 1983 to 27 percent in 1999. The Green Party managed to establish itself in parliament from 1986 onwards.

Austria became a member of the European Union in 1995 and retained its constitutional neutrality, like some other EU members, such as Sweden.

Historic maps

Government and politics

Austria's constitution characterizes the republic as a federation consisting of nine autonomous federal states. Both the federation and all its states have written constitutions defining them to be republican entities governed according to the principles of representative democracy. Austria's government structure is surprisingly similar to that of incomparably larger federal republics such as Germany or the United States. A convention, called the Österreich–Konvent was convened in 2003 to reform the constitution, but has failed to produce a proposal that would receive the two thirds of votes in the Nationalrat necessary for constitutional amendments and/or reform.

Constitutional structure

The chief of state is the president, who is elected by direct popular vote for a six-year term, and is eligible for a second term. The head of government is the chancellor, who is formally chosen by the president but determined by the coalition parties forming a parliamentary majority. The vice chancellor chosen by the president on the advice of the chancellor.

The bicameral Federal Assembly, or Bundesversammlung, consists of Federal Council or Bundesrat, which has 62 members who are chosen by state parliaments with each state receiving three to 12 members, according to its population, to serve a five- or six-year term, and the National Council, or Nationalrat, which has 183 members elected by direct popular vote to serve four-year terms, by proportional representation. Seats in the Nationalrat are awarded to political parties that have obtained at least four percent of the general vote, or alternatively, have won a direct seat, or Direktmandat, in one of the 43 regional election districts. This "four percent hurdle" prevents a large splintering of the political landscape in the Nationalrat. Suffrage is universal to those aged 18 years and over.

The judiciary comprises the Supreme Judicial Court, the Administrative Court, and Constitutional Court. The legal system is based on civil law system originating from Roman law. There is judicial review of legislative acts by the Constitutional Court, and there are separate administrative and civil/penal supreme courts. Austria accepts compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction.

Administrative divisions

A federal republic, Austria is divided into nine states. These states are then divided into districts and cities. Districts are subdivided into municipalities. Cities have the competencies otherwise granted to both districts and municipalities. The states are not mere administrative divisions but have some distinct legislative authority separate from the federal government.

Perpetual neutrality

The 1955 Austrian State Treaty ended the occupation of Austria following World War II and recognized Austria as an independent and sovereign state. In October 1955, the Federal Assembly passed a constitutional law in which "Austria declares of her own free will her perpetual neutrality." The second section of this law stated that "in all future times Austria will not join any military alliances and will not permit the establishment of any foreign military bases on her territory." Since then, Austria has shaped its foreign policy on the basis of neutrality. Austria began to reassess its definition of neutrality following the fall of the Soviet Union, granting overflight rights for the UN-sanctioned action against Iraq in 1991, and, since 1995, contemplating participation in the EU's evolving security structure. Also in 1995, it joined the Partnership for Peace and subsequently participated in peacekeeping missions in Bosnia. Austria attaches great importance to participation in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development and other international economic organizations, and it has played an active role in the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE).

Energy politics

In 1972, the country began construction of a nuclear-powered electricity-generation station at Zwentendorf on the River Danube, following a unanimous vote in parliament. However, in 1978, a referendum voted approximately 50.5 percent against nuclear power, 49.5 percent for, and parliament subsequently unanimously passed a law forbidding the use of nuclear power to generate electricity. Austria produces more than half of its electricity by hydropower. Together with other renewable energy sources such as wind, solar and biomass powerplants, the electricity supply from renewable energy amounts to nearly 80 percent of total use in Austria. The rest is produced by gas and oil powerplants.

Military

The main branches of the Austrian Armed Forces ("Bundesheer") are Joint Forces which consist of Land Forces, Air Forces, International Missions, and Special Forces; next to Mission Support and Command Support. In 2004, Austria spent about 0.9 percent of its GDP on defense. The army had about 45,000 soldiers in 2007, of which about half were conscripts.

With the end of the Cold War, and more importantly the removal of the former heavily guarded "Iron Curtain" separating Austria and Hungary, the Austrian military have been helping Austrian border guards to prevent border crossings by illegal immigrants. This assistance was to end when Hungary joined the EU Schengen area in 2008, abolishing "internal" border controls between treaty states. Some politicians have called for a prolongation of this mission, but the legality of this is heavily disputed. In accordance with the Austrian constitution, armed forces may only be deployed in a limited number of cases, mainly to defend the country and aid in cases of national emergencies, such as in the wake of natural disasters etc. They may generally not be used as auxiliary police forces.

Austria has a long tradition of engaging in UN-led peacekeeping and other humanitarian missions. The Austrian Forces Disaster Relief Unit (AFDRU), in particular, an all-volunteer unit with close ties to civilian specialists (rescue dog handlers, etc) enjoys a reputation as a quick (standard deployment time is 10 hours) and efficient SAR unit. In 2007, larger contingents of Austrian forces were deployed in Bosnia, Kosovo and, since 1974, on the Golan Heights.

Economy

Austria has a well-developed social market economy, similar in structure toGermany's. The country has a very high standard of living in which the government has played an important role in its citizen's life ever since 1945. Its principal economic activities include finance and consulting, tourism, iron and steel works, chemical plants and oil corporations, and a small, but highly developed agricultural sector.

The people of Austria enjoy a high standard of living. The service sector generates the vast majority of Austria's GDP. Vienna has grown into a finance and consulting metropole and has established itself as the door to the east within the last decades. Viennese law firms and banks are among the leading corporations in business with the new EU member states.

Important for Austria's economy is tourism, both winter and summer tourism. Its dependency on German guests has made this sector of Austrian economy dependent on German economy, however recent developments have brought a change, especially since winter ski resorts such as Arlberg or Kitzbühel are now more and more frequented by Eastern Europeans, Russians and Americans.

Ever since the end of the World War II, Austria has achieved sustained economic growth. In the 1950s, the rebuilding efforts for Austria lead to an average annual growth rate of more than five percent. Many of the country's largest firms were nationalized in the early post-war period to protect them from Soviet takeover as war reparations. For many years, the government and its state-owned industries conglomerate played an important role in the Austrian economy. However, starting in the early 1990s, the group was broken apart, and state-owned firms started to operate largely as private businesses, and a great number of these firms were wholly or partially privatized. Although the government's privatization work in past years has been successful, it still operates some firms, state monopolies, utilities, and services.

Austria has a strong labor movement. The Austrian Trade Union Federation (ÖGB) comprises constituent unions with a total membership of about 1.5 million—more than half the country's wage and salary earners. Since 1945, the ÖGB has pursued a moderate, consensus-oriented wage policy, cooperating with industry, agriculture, and the government on a broad range of social and economic issues in what is known as Austria's "social partnership."

Germany has historically been the main trading partner of Austria, making it vulnerable to rapid changes in the German economy. But since Austria became a member state of the European Union it has gained closer ties to other European Union economies, reducing its economic dependence on Germany. In addition, membership in the EU has drawn an influx of foreign investors attracted by Austria's access to the single European market and proximity to EU aspiring economies.

Export commodities include machinery and equipment, motor vehicles and parts, paper and paperboard, metal goods, chemicals, iron and steel, textiles, and foodstuffs. Export partners include Germany, [[Italy], U.S., and Switzerland. Import commodities include machinery and equipment, motor vehicles, chemicals, metal goods, oil and oil products; and foodstuffs. Import partners include Germany, Italy, Switzerland, and Netherlands.

Demographics

Population

Austria's total population is close to 9 million. The population of the capital, Vienna, is close to million (2.6 million including its suburbs), representing about a quarter of the country's population, and is known for its vast cultural offerings and high standard of living.

Ethnicity

Austrians make up the large majority of the population, while former Yugoslavs (including Croatians, Slovenes, Serbs, and Bosniaks), Turks, Germans, and others make up the rest. Austrians are a homogeneous people, although several decades of strong immigration have significantly altered the composition of the population of Austria.

German-speaking Austrians form by far the country's largest group of Austria's population. The Austrian federal states of Carinthia and Styria are home to a significant (indigenous) Slovenian minority, while Hungarians and ,Croatians live in the east-most Bundesland, Burgenland (formerly part of the Hungarian half of Austria-Hungary). The remainder of Austria's people are of non-Austrian descent, many from surrounding countries, especially from the former East Bloc nations. So-called guest workers (Gastarbeiter) and their descendants, as well as refugees from Yugoslav wars and other conflicts, also form an important minority group in Austria. Since 1994 the Roma and Sinti (gypsies) are an officially recognized ethnic minority in Austria

Some of the Austrian states introduced standardized tests for new citizens, to assure their language and cultural knowledge and accordingly their ability to integrate into the Austrian society.

Religion

Among religions in Austria, Roman Catholic Christianity is the predominant one. The remaining people include adherents to Eastern Orthodox Churches and Judaism, as well as those who have no religion. The influx of Eastern Europeans, especially from the former Yugoslav nations, Albania and particularly from Turkey largely contributed to a substantial Muslim minority in Austria. Buddhism, which was legally recognized as a religion in Austria in 1983, enjoys widespread acceptance.

Austria was greatly affected by the Protestant reformation, to the point where a majority of the population was eventually Protestant. Due to the prominent position of the Habsburgs in the Counter-Reformation, however, Protestantism was all but wiped out and Catholicism once more restored to the dominant religion. The significant Jewish population (around 200,000 in 1938) in the country, mainly residing in Vienna, was reduced to a mere couple of thousand by the mass emigration in 1938 (more than two thirds of the Jewish population emigrated from 1938 until 1941) and the following Holocaust during the Nazi regime in Austria. Immigration in more recent years, primarily from Turkey and the former Yugoslavia, has led to an increase in the number of Muslims and Serbian Orthodox Christians.

Language

The official language of Austria is German. Austria's mountainous terrain led to the development of numerous dialects, all of which belong to Austro-Bavarian groups of German dialects, with the exception of the dialect spoken in its west-most Bundesland, Vorarlberg, which belongs to the group of Alemannic dialects. There is also a distinct grammatical standard for Austrian German with a few differences to the German spoken in Germany.

Men and women

Most Austrians consider it women's work to do household chores, cook, and care for children. Austrian women work outside the home less frequently than women in other European countries, and women tend to be under-represented in business and the professions. Despite equal-pay, most women are paid less than men for the same type of job. Austrian men, especially among older and rural families, are still considered the head of the family. Men have compulsory military service and work in industry, farming, trades, and professions. Austrian men have a high suicide rate.

Marriage and the family

After a boom in marriages from 1945 through the 1960s, by the late twentieth century, fewer young people marry, more couples divorce, more raise children without marrying. Couples marry later, and educated women choose their career over a family. No-fault divorce has accompanied an increase in marriage break-ups. The domestic unit is the nuclear family of husband, wife, and children, as well as single-parent households, homes of divorced or widowed people, single professionals, and households where a man and woman raise children outside of marriage. Rural households may include extended families. Regarding inheritance of farms, the most common practice is passing the property to one son, while remaining siblings receive cash for their share of the property.

Education

Optional kindergarten education is provided for all children between the ages of three and six years. School attendance is compulsory for nine years, ie usually to the age of 15. Primary education lasts for four years. Alongside Germany, secondary education includes two main types of schools based on a pupil's ability as determined by grades from the primary school: the Gymnasium for the more gifted children which normally leads to the Matura which is a requirement for access to universities, and the Hauptschule which prepares pupils for vocational education.

The Austrian university system had been open to any student who passed the Matura examination until 2006, when legislation allowed the introduction of entrance exams for studies such as Medicine. In 2006, all students were charged a fee of about €370 per semester for all university studies. An OECD report criticized the Austrian education system for the low number of students attending universities and the overall low number of academics compared to other OECD countries. Regarding literacy, 98 percent of the total population over the age of 15 could read and write in 2003.

Class

In the early 1800s, Austrian society consisted of aristocrats, "citizens," and peasant-farmers or peasant-serfs. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the aristocracy diminished and a small middle class of entrepreneurs, and a larger working class, were added to the existing structure. After World War II, the middle class expanded, so that by the late twentieth century there were more middle-class citizens than any other group. Education was considered the means to upward mobility in 2007. Equality was promoted, although foreign workers, immigrants, and Gypsies were less accepted. An old Austrian family lineage and inherited wealth remain symbols of status in Austrian culture. Wealth is displayed in a second home and more material possessions.

Culture

Culture in the territory of what is today Austria can be traced back to around 1050 B.C.E. with the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures. However, a culture of Austria as we know it today began to take shape when the Austrian lands were part of the Holy Roman Empire, with the Privilegium Minus of 1156, which elevated Austria to the status of a Duchy, marking an important step in its development. Austrian culture has largely been influenced by its neighbors, Italy, Germany, Hungary and Bohemia.

Architecture

Austria is famous for its castles, palaces, and cemeteries, among other architectural works. Some of Austria's most famous castles include the Burg Hohenwerfen, Castle Liechtenstein (built during the twelfth century, was destroyed by the Ottomans in 1529 and 1683, and remained in ruins until 1884, when it was rebuilt), and the Schloß Artstetten. Many of Austria's castles were created during the Habsburg reign.

Austria is known for its cemeteries. Vienna has 50 different cemeteries, of which the Zentralfriedhof is the most famous. The Habsburgs are housed in the Imperial Crypt. Austria is rich in Roman Catholic tradition. One of Austria's oldest cathedrals is the Minoritenkirche in Vienna. It was built in the Gothic style in the year 1224. One of the world's tallest cathedrals, the 136-meter-tall (446-foot-tall) Stephansdom is the seat of the Archbishop of Vienna; the Stephansdom is 107 meters (351 feet) long and 34 meters (111.5 feet) wide. Stift Melk is a Benedictine abbey in the federal state of Lower Austria, overlooking the Danube as it flows through the Wachau valley. The abbey was formed in 1089 on a rock above the city of Melk.

Two of the most famous Austrian palaces are the Belvedere and Schönbrunn. The baroque-style Belvedere palace was built in the period 1714–1723, by Prince Eugene of Savoy, and now is home to the Austrian Gallery. The Schönbrunn palace was built in 1696 by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach for Emperor Leopold I; empress Maria Theresa of Austria ordered the palace restyled in Rococo; in 1996, it was added to the United Nations' World Cultural Heritage list.

The Semmering Railway, a famous engineering project constructed in the years 1848–1854, was the first European mountain railway built with a standard-gauge track. Still fully functional, it is now part of the Austrian Southern Railway.

Art

Vienna was a center for the fine arts as well as for music and the theater. Realist painter Ferdinand G. Waldmuller and painter Hans Makart were the most famous of the nineteenth century. The Vienna Secession was part of a varied movement around 1900 that is now covered by the general term Art Nouveau. Major figures of the Vienna Secession were Otto Wagner, Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, and Koloman Moser. Oskar Kokoschka painted the realities of World War I. In the twentieth century, artists such as Herbert Boeckl painted ornamentation on residential blocs and cathedrals. Anton Kolig and Josef Mikl were abstract painters, and Ernest Fuchs and Anton Lehmden were known for "fantastic realism." Friedensreich Regentag Dunkelbunt Hundertwasser, an Austrian painter, and sculptor, was by the end of the terntieth century was arguably the best-known contemporary Austrian artist. Hundertwasser's original, unruly, artistic vision expressed itself in pictorial art, environmentalism, philosophy, and design of facades, postage stamps, flags, and clothing (among other areas).

Cinema

In the silent movie era, Austria was one of the leading producers of movies. Many of the Austrian directors, actors, authors and cinematographers also worked in Berlin. The most famous was Fritz Lang, the director of Metropolis. Following the Anschluss, the German annexation of Austria in 1938, many Austrian directors emigrated to the United States, including Erich von Stroheim, Otto Preminger, Billy Wilder, Hedy Lamarr, Mia May, Richard Oswald and Josef von Sternberg.

Cuisine

Austria's cuisine is derived from the cuisine of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In addition to native regional traditions, it has been influenced above all by Hungarian, Czech, Jewish, Italian and Bavarian cuisines, from which both dishes and methods of food preparation have often been borrowed. Goulash is one example of this. Austrian cuisine is known primarily in the rest of the world for its pastries and sweets. In recent times a new regional cuisine has also developed which is centered on regional produce and employs modern and easy methods of preparation. The Austrian Cuisine is therefore one of the most multi and transcultural cuisines in Europe. Typical Austrian dishes include Wiener Schnitzel, Schweinsbraten, Kaiserschmarren, Knödel, Sachertorte and Tafelspitz. There are also Kasnockn, a macaroni dish with fresh Pinzgauer cheese and parsley, and Eierschwammerl dishes. The Eierschwammerl are the native yellow, tan mushrooms. These mushrooms are delicious, especially when in a thick Austrian soup, or on regular meals. The candy PEZ was invented in Austria. Austria is also famous for its Apfelstrudel.

There are many different types of Austrian beer. The most common style of beer is called Märzen which is roughly equivalent to the English lager or Bavarian Helles. Among the multitude of local and regional breweries, certain brands are available nationally. One of the most common brands of beer to be found in Austria is Stiegl, founded in 1492. Stiegl brews both a helles (a light lager) and a Weissbier (Hefeweizen), as well as other specialty beers. Ottakringer from Vienna can be found more often in the eastern provinces. Among Styrian breweries, in the south, are the popular Gösser, Puntigamer and Murauer brands. Hirter is produced in the town of Hirt in Carinthia. In Lower Austria Egger, Zwettler, Schwechater, and the popular Wieselburger predominate.

Dance

Austrian folk dancing is mostly associated with Schuhplattler, Ländler, Polka or Waltz. However, there are other dances such as Zwiefacher, Kontratänze and Sprachinseltänze. In Austria, folk dances in general are known as Folkloretänze, i.e. "folklore dances," whereas the Austrian type of folk dance is known as Volkstanz (literally "folk dance"). Figure dancing is a type of dance where different figures are put together with a certain tune and given a name. Round dancing, which includes the waltz, the polka, Zwiefacher etc, involves basic steps which can be danced to different tunes. In folk dancing, the waltz and the polka are in a slightly different form to standard ballroom dancing. Sprachinseltänze (literally "language island dances") are those dances which are actually by German-speaking minorities (see German as a Minority Language) living outside Austria, but which originate in Austria, e.g. those of Transylvania. One example of this type of dance is the Rediwa.

Literature

Austrian literature is the German language literature written in Austria. The first significant literature in German appeared in Austria in the form of epic poems and songs around 1200. Austrian literature can be divided into two main divisions, namely the period up until the mid twentieth century, and the period subsequent, after both the Austro-Hungarian and German empires were gone. Austria went from being a major European power, to being a small country. In addition, there is a body of literature that some would deem Austrian but is not written in German. Complementing its status as a land of artists, Austria has always been a country of great poets, writers, and novelists. It was the home of novelists Arthur Schnitzler, Stefan Zweig, Thomas Bernhard, and Robert Musil, and of poets Georg Trakl, Franz Werfel, Franz Grillparzer, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Adalbert Stifter. Famous contemporary Austrian playwrights and novelists include Elfriede Jelinek and Peter Handke.

Music

Austria has been the birthplace of many famous composers such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Joseph Haydn, Franz Schubert, Anton Bruckner, Johann Strauss, Sr., Johann Strauss, Jr. and Gustav Mahler as well as members of the Second Viennese School such as Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern and Alban Berg.

Vienna has long been especially an important center of musical innovation. Eighteenth and nineteenth century composers were drawn to the city due to the patronage of the Habsburgs, and made Vienna the European capital of classical music. During the Baroque period, Slavic and Hungarian folk forms influenced Austrian music. Vienna's status began its rise as a cultural center in the early 1500s, and was focused around instruments including the lute. Ludwig van Beethoven spent the better part of his life in Vienna.

Austria's current national anthem was chosen after World War II to replace the traditional Austrian anthem by Joseph Haydn. The composition, which was initially attributed to Mozart, was most likely not composed by Mozart himself.

Austria has also produced one notable jazz musician, keyboardist Josef Zawinul who helped pioneer electronic influences in jazz as well as being a notable composer in his own right.

Philosophy

In addition to physicists, Austria was the birthplace of two of the greatest philosophers of the twentieth century, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Karl Popper. In addition to them biologists Gregor Mendel and Konrad Lorenz as well as mathematician Kurt Gödel and engineers such as Ferdinand Porsche and Siegfried Marcus were Austrians.

Science and technology

Austria was the cradle of numerous scientists with international reputations. Among them are Ludwig Boltzmann, Ernst Mach, Victor Franz Hess and Christian Doppler, prominent scientists in the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, contributions by Lise Meitner, Erwin Schrödinger and Wolfgang Pauli to nuclear research and quantum mechanics were key to these areas' development during the 1920s and 1930s. A present-day quantum physicist is Anton Zeilinger, noted as the first scientist to demonstrate quantum teleportation.

A focus of Austrian science has always been medicine and psychology, starting in medieval times with Paracelsus. Eminent physicians like Theodore Billroth, Clemens von Pirquet, and Anton von Eiselsberg have built upon the achievements of the nineteenth century Vienna School of Medicine. Austria was home to psychologists Sigmund Freud, Alfred Adler, Paul Watzlawick and Hans Asperger and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl.

The Austrian School of Economics, which is prominent as one of the main competitive directions for economic theory is related to Austrian economists Joseph Schumpeter, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, Ludwig von Mises, and Friedrich Hayek. Other noteworthy Austrian-born émigrés include the management thinker Peter Drucker and the 38th Governor of California, Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Sports

Parts of Austria are located in the Alps which makes it a prime location for skiing. Austria is the leading nation in the Alpine Skiing World Cup (consistently winning the largest number of points of all countries) and also strong in many other winter sports such as ski jumping. Austria's national ice hockey team ranks 13th in the world.

Austria (particularly Vienna) also has an old tradition in football, even though, since World War II, the sport has more or less been in decline. The Austrian championship (originally only limited to Vienna, as there were no professional teams elsewhere), has been held since 1912. The Austrian Cup has been held since 1913. The Austria national football team has qualified for 7 World Cups however has not ever qualified in its history to the European Championship, though that will change with the 2008 Tournament as they qualify as co-hosts with Switzerland. The governing body for football in Austria is the Austrian Football Association.

The first official world chess champion, Wilhelm Steinitz was from the Austrian Empire.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 CIA, Austria World Factbook. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Austria International Monetary Fund. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ↑ Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene United Nations Development Programme, December 15, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beller, Steven. A Concise History of Austria. (Cambridge Concise Histories.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0521478863

- Bérenger, Jean. A History of the Habsburg Empire. London: Longman, 1994. ISBN 978-0582090095

- Brook-Shepherd, Gordon. The Austrians: A Thousand-year Odyssey. London: HarperCollins, 1997. ISBN 978-0006382553

- Jelavich, Barbara. Modern Austria Empire and Republic, 1815-1986. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0521316255

- Sully, Melanie A. A Contemporary History of Austria. London: Routledge, 1990. ISBN 978-0415019286

External links

All links retrieved August 22, 2023.

- Austria CIA World Factbook.

- Culture of Austria Countries and Their Cultures.

- Austria Encyclopaedia Britannica Online.

- Austria BBC Country Profiles.

- Austria U.S. Department of State.

- Austria The Economist.

- Austrian Law Rechtsfreund.at.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Austria history

- Geography_of_Austria history

- History_of_Austria history

- Hallstatt_culture history

- Noricum history

- Severinus_of_Noricum history

- Rupert_of_Salzburg history

- March_of_Austria history

- Rudolf_IV_Duke_of_Austria history

- Congress_of_Vienna history

- Prince_Klemens_Wenzel_von_Metternich history

- Austrofascism history

- Anschluss history

- Economy_of_Austria history

- Demographics_of_Austria history

- Religion_in_Austria history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.