Asthma

Asthma is a chronic disease of the respiratory system in which the airway occasionally constricts, becomes inflamed, and is lined with excessive amounts of mucus, often in response to one or more triggers. This airway narrowing causes symptoms such as wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and coughing, which respond to bronchodilators. A bronchodilator is a medication intended to improve bronchial airflow by acting on β2 receptors in bronchial smooth muscle and bronchial mucus membranes.

These acute episodes may be triggered by such things as exposure to an environmental stimulant (or allergen, a substance causing an allergic reaction), cold air, exercise or exertion, or emotional stress. In children, the most common triggers are viral illnesses such as those that cause the common cold.[1]

The symptoms of asthma, which can range from mild to life threatening, can usually be controlled with a combination of drugs and environmental changes. Between episodes, most patients feel fine. There is no cure for asthma. But human creativity has been applied to develop a myriad of ways to prevent attacks and relieve symptoms, such as tightness of the chest and trouble breathing.

Public attention in the developed world has recently focused on asthma because of its rapidly increasing prevalence, affecting up to one in four urban children.[2]

History

The word asthma is derived from the Greek aazein, meaning "sharp breath." The word first appears in Homer's Iliad;[3] Hippocrates was the first to use it in reference to the medical condition. Hippocrates thought that the spasms associated with asthma were more likely to occur in tailors, anglers, and metalworkers.

Six centuries later, Galen wrote much about asthma, noting that it was caused by partial or complete bronchial obstruction. Moses Maimonides, an influential medieval rabbi, philosopher, and physician, wrote a treatise on asthma, describing its prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.[4] In the seventeenth century, Bernardino Ramazzini noted a connection between asthma and organic dust.

The use of bronchodilators started in 1901, but it was not until the 1960s that the inflammatory component of asthma was recognized, and anti-inflammatory medications were added to the regimen.

Causes

As noted above, there are many possible triggers, including exercise or exertion, emotional stress, and exposure to an allergen or cold air, as well viral illness such as the common cold.[1]

Many studies have linked asthma, bronchitis, and acute respiratory illnesses to air quality experienced by children. One of the largest of these studies is the California Children's Health Study:

The study showed that children in the high ozone communities who played three or more sports developed asthma at a rate three times higher than those in the low ozone communities. Because participation in some sports can result in a child drawing up to 17 times the “normal” amount of air into the lungs, young athletes are more likely to develop asthma.[5]

Diagnosis

In most cases, a physician can diagnose asthma on the basis of typical findings in a patient's clinical history and examination. Asthma is strongly suspected if a patient suffers from eczema (an inflamed skin condition) or other allergic conditions—suggesting a general atopic (allergy-related) constitution—or has a family history of asthma. While measurement of airway function is possible for adults, most new cases are diagnosed in children who are unable to perform such tests. Diagnosis in children is based on a careful compilation and analysis of the patient's medical history and subsequent improvement with an inhaled bronchodilator medication. In adults, diagnosis can be made with a peak flow meter (which tests airway restriction), looking at both the diurnal variation and any reversibility following inhaled bronchodilator medication.

Testing peak flow at rest (or baseline) and after exercise can be helpful, especially in young asthmatics who may experience only exercise-induced asthma. If the diagnosis is in doubt, a more formal lung function test may be conducted. Once a diagnosis of asthma is made, a patient can use peak flow meter testing to monitor the severity of the disease.

Differential diagnosis

Before diagnosing someone as asthmatic, alternative possibilities should be considered. A physician taking a history should check whether the patient is using any known bronchoconstrictors (substances that cause narrowing of the airways, e.g., certain anti-inflammatory agents or beta-blockers).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which closely resembles asthma, is correlated with exposure to cigarette smoke, an older patient, less symptom reversibility after bronchodilator administration (as measured by spirometry, or measuring of breath), and decreased likelihood of family history of atopy.

Pulmonary aspiration (the entry of secretions or foreign material into the trachea and lungs), whether direct due to dysphagia (swallowing disorder) or indirect (due to acid reflux), can show similar symptoms to asthma. However, with aspiration, fevers might also indicate aspiration pneumonia, which is caused by a bacterial infection or direct chemical insult. Direct aspiration (dysphagia) can be diagnosed by performing a Modified Barium Swallow Test (a test involving X-rays, in which the swallowing mechanism of the patient can be viewed on a video screen) and can be treated with feeding therapy by a qualified speech therapist.

Only a minority of asthma sufferers have an identifiable allergy trigger. The majority of these triggers can often be identified from the history; for instance, asthmatics with hay fever or pollen allergy will have seasonal symptoms, those with allergies to pets may experience an abatement of symptoms when away from home, and those with occupational asthma may improve during leave from work. Occasionally, allergy tests are warranted and, if positive, may help in identifying avoidable symptom triggers.

After pulmonary function has been measured, radiological tests, such as a chest X-ray or computed tomography (CT) scan, may be required to exclude the possibility of other lung diseases. In some people, asthma may be triggered by gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), a disease where improper functioning of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) allows leakage of stomach contents back into the esophagus. This disease can be treated with suitable antacids. Very occasionally, specialized tests after inhalation of methacholine—or, even less commonly, histamine—may be performed.

Asthma is categorized by the United States National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute as mild persistent, moderate persistent, and severe persistent. The diagnosis of "severe persistent asthma" occurs when symptoms are continual with frequent exacerbations and frequent nighttime symptoms and results in limited physical activity, and when lung function as measured by PEV or FEV1 tests is less than 60 percent predicted with PEF variability greater than 30 percent.

Epidemiology

Asthma is usually diagnosed in childhood. The risk factors for asthma include:

- a personal or family history of asthma or atopy;

- triggers (see Pathophysiology above);

- premature birth or low birth weight;

- viral respiratory infection in early childhood;

- maternal smoking;

- being male, for asthma in prepubertal children; and

- being female, for persistence of asthma into adulthood.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that asthma is the most common chronic disease among children.[6] Although asthma is more common in affluent countries, it is by no means a problem restricted to such nations. It occurs in all countries regardless of level of development. According to the WHO, over 80 percent of asthma deaths occurs in low- and lower-middle income countries.[6]

Asthma and athletics

Asthma appears to be more prevalent in athletes than in the general population. One survey of participants in the 1996 Summer Olympic Games showed that 15 percent had been diagnosed with asthma, and that 10 percent were taking asthma medication.[7] These statistics have been questioned on at least two bases. For one, persons with mild asthma may be more likely to be diagnosed with the condition than others because even subtle symptoms may interfere with their performance and lead to pursuit of a diagnosis. Second, it has also been suggested that some professional athletes who do not suffer from asthma claim to in order to obtain special permits to use certain performance-enhancing drugs.

There appears to be a relatively high incidence of asthma in sports such as cycling, mountain biking, and long-distance running, and a relatively lower incidence in weightlifting and diving. It is unclear how much of these disparities are from the effects of training in the sport, and from self-selection of sports that may appear to minimize the triggering of asthma.[7][8]

In addition, there exists a variant of asthma called exercise-induced asthma that shares many features with allergic asthma. It may occur either independently or concurrently with the latter. Exercise studies may be helpful in diagnosing and assessing this condition.

Socioeconomic factors

The incidence of asthma is higher among low-income populations within a society (even though it is more common in developed countries than developing countries). In the Western world these are disproportionately minority, and more likely to live near industrial areas. Additionally, asthma has been strongly associated with the presence of cockroaches in living quarters, which is more likely in such neighborhoods.

The quality of asthma treatment varies along racial lines, likely because many low-income people cannot afford health insurance and because there is still a correlation between class and race. For example, black Americans are less likely to receive outpatient treatment for asthma despite having a higher prevalence of the disease, they are more likely to have emergency room visits or hospitalization for asthma, and they are three times as likely to die from an asthma attack compared to white Americans. The prevalence of "severe persistent" asthma is also greater in low-income communities compared with communities with better access to treatment.[9]

Pathophysiology

Asthma and gastro-esophageal reflux disease

If gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is present, the patient may have repetitive episodes of acid aspiration, which results in airway inflammation and "irritant-induced" asthma. GERD may be common in difficult-to-control asthma, but generally speaking, treating it does not seem to affect the asthma.[10]

Asthma and sleep apnea

It is recognized with increasing frequency that patients who have both obstructive sleep apnea (OSA, a condition where one stops breathing during sleep due to obstruction of the airway) and bronchial asthma, often improve tremendously when the sleep apnea is diagnosed and treated.[11] Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) (a mechanism where air is directly delivered into the airway) is used to treat OSA.

Bronchial inflammation

The mechanisms behind allergic asthma—i.e., asthma resulting from an immune response to inhaled allergens—are the best understood of the causal factors. In both asthmatics and non-asthmatics, inhaled allergens that find their way to the inner airways are ingested by a type of cell known as antigen presenting cells, or APCs. APCs then "present" pieces of the allergen to other immune system cells. In most people, these other immune cells (TH0 cells, or T helper cells) "check" and usually ignore the allergen molecules. In asthmatics, however, these cells transform into a different type of cell (TH2), for reasons that are not well understood. The resultant TH2 cells activate an important arm of the immune system, known as the humoral immune system. The humoral immune system produces antibodies against the inhaled allergen.

Later, when an asthmatic inhales the same allergen, these antibodies "recognize" it and activate a humoral response. Inflammation results and chemicals are produced that cause the airways to constrict and release more mucus, and the cell-mediated arm of the immune system is activated. The inflammatory response is responsible for the clinical manifestations of an asthma attack. The following section describes this complex series of events in more detail.

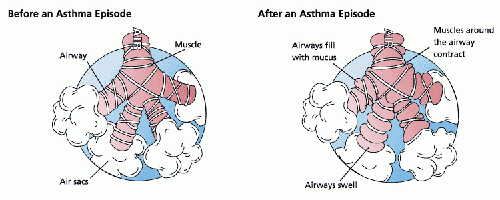

Bronchoconstriction

During an asthma episode, inflamed airways react to environmental triggers such as smoke, dust, or pollen. The airways narrow and produce excess mucus, making it difficult to breathe. In essence, asthma is the result of an immune response in the bronchial airways.[12]

The airways of asthmatics are "hypersensitive" to certain triggers, also known as stimuli. In response to exposure to these triggers, the bronchi (large airways) contract into spasm (an "asthma attack"). Inflammation soon follows, leading to a further narrowing of the airways and excessive mucus production, which leads to coughing and other breathing difficulties.

There are several categories of stimuli:

- allergenic air pollution, from nature, typically inhaled, which include waste from common household insects, such as the house dust mites and cockroaches, grass pollen, mold spores, and pet epithelial cells;

- medications, including aspirin[13] and β-adrenergic antagonists (i.e. beta blockers, a class of drugs usually used for the management of cardiac arrhythmias (irregular heart contraction) and cardioprotection after myocardial infarction (i.e. a heart attack);

- use of fossil fuel related allergenic air pollution, such as ozone, smog, summer smog (aka photochemical smog, resulting from the reaction of sunlight with nitrogen oxides and hydrocarbons), nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide, which is thought to be one of the major reasons for the high prevalence of asthma in urban areas;

- various industrial compounds and other chemicals, notably sulfites; chlorinated swimming pools generate chloramines—monochloramine (NH2Cl), dichloramine (NHCl2) and trichloramine (NCl3)—in the air around them, which are known to induce asthma;[14]

- early childhood infections, especially viral respiratory infections. However, persons of any age can have asthma triggered by colds and other respiratory infections even though their normal stimuli might be from another category (e.g. pollen) absent at the time of infection. 80 percent of asthma attacks in adults and 60 percent in children are caused by respiratory viruses;

- exercise, the effects of which differ somewhat from those of the other triggers;

- (in some countries) - allergenic indoor air pollution from newsprint and other literature such as junk mail leaflets & glossy magazines;

- emotional stress which is poorly understood as a trigger.

Pathogenesis

(See also: Allergy).

The fundamental problem in asthma appears to be immunological: young children in the early stages of asthma show signs of excessive inflammation in their airways. Epidemiological findings give clues as to the pathogenesis (or its origin): the incidence of asthma seems to be increasing worldwide, and asthma is now much more common in affluent countries.

In 1968, Andor Szentivanyi first described The Beta Adrenergic Theory of Asthma; in which blockage of the Beta-2 receptors of pulmonary smooth muscle cells causes asthma.[15] While it is now known that the pathophysiology of asthma is multifactorial, the Beta-2-adrenergic receptor and its signaling pathway remain sentinel to the pathogenesis and treatment of asthma.[16]

One theory of pathogenesis is that asthma is a disease of hygiene. In nature, babies are exposed to bacteria and other antigens soon after birth, "switching on" the TH1 lymphocyte cells of the immune system that deal with bacterial infection. If this stimulus is insufficient—as it may be in modern, clean environments—then TH2 cells predominate, and asthma and other allergic diseases may develop. This "hygiene hypothesis" may explain the increase in asthma in affluent populations. The TH2 lymphocytes and eosinophil cells (both types of white blood cells involved in immune response) that protect us against parasites and other infectious agents are the same cells responsible for the allergic reaction. The Charcot-Leyden crystals are formed when the crystalline material in eosinophils coalesce. These crystals are significant in sputum (e.g. mucus or phlegm) samples of people with asthma. In the developed world, these parasites are now rarely encountered, but the immune response remains and is wrongly triggered in some individuals by certain allergens.

Another theory is based on the correlation of air pollution and the incidence of asthma. Although it is well known that substantial exposures to certain industrial chemicals can cause acute asthmatic episodes, it has not been proven that air pollution is responsible for the development of asthma.

Finally, it has been postulated that some forms of asthma may be related to infection, in particular by Chlamydia pneumoniae.[17] This issue remains controversial, as the relationship between the infection and onset is unclear.

Prognosis

The prognosis for asthmatics is good, especially for children with mild disease.

For asthmatics diagnosed during childhood, 54 percent will no longer carry the diagnosis after a decade. The extent of permanent lung damage in asthmatics is unclear. Airway remodeling is observed, but it is unknown whether these represent harmful or beneficial changes.[12] Although conclusions from studies are mixed, most studies show that early treatment with glucocorticoids (a type of steroid hormone) prevents or ameliorates decline in lung function as measured by several parameters.[18] For those who continue to suffer from mild symptoms, corticosteroids can help most to live their lives with few disabilities. The mortality rate for asthma is low, with around six thousand deaths per year in a population of some ten million patients in the United States.[19] Better control of the condition may help prevent some of these deaths.

Signs and symptoms

In some individuals, asthma is characterized by chronic respiratory impairment. In others, it is an intermittent illness marked by episodic symptoms that may result from a number of triggering events, including upper respiratory infection, airborne allergens, and exercise.

Signs of an asthmatic episode or asthma attack are shortness of breath (dyspnea), either stridor (a high-pitched breathing noise caused by obstruction of the airway) or wheezing, rapid breathing (tachypnea), prolonged expiration, a rapid heart rate (tachycardia), rhonchous lung sounds (audible through a stethoscope), and over-inflation of the chest. During a serious asthma attack, the accessory muscles of respiration (sternocleidomastoid and scalene muscles of the neck) may be used, shown as in-drawing of tissues between the ribs and above the sternum and clavicles, and the presence of a paradoxical pulse (a pulse that is weaker during inhalation and stronger during exhalation).

Although stridor is "often regarded as the sine qua non of asthma,"[19] some victims primarily exhibit coughing, and in the late stages of an attack, air motion may be so impaired that no wheezing may be heard. When present the cough may sometimes produce clear sputum.

During very severe attacks, an asthma sufferer can turn blue from lack of oxygen, and can experience chest pain or even loss of consciousness. Severe asthma attacks may lead to respiratory arrest and death. Despite the severity of symptoms during an asthmatic episode, between attacks an asthmatic may show few signs of the disease.

Treatment

The most effective treatment for asthma is identifying triggers, such as pets or aspirin, and limiting or eliminating exposure to them. Desensitization to allergens has been shown to be a treatment option for certain patients. Desensitization to allergens involves the gradual increase of direct injection of the allergen into the patient, which may cause the immune system to grow less sensitive to the allergen.

As is common with respiratory disease, smoking adversely affects asthmatics in several ways, including an increased severity of symptoms, a more rapid decline of lung function, and decreased response to preventive medications.[20]

Asthmatics who smoke typically require additional medications to help control their disease. Furthermore, exposure of both nonsmokers and smokers to secondhand smoke is detrimental, resulting in more severe asthma, more emergency room visits, and more asthma-related hospital admissions.[21] Smoking cessation and avoidance of secondhand smoke is strongly encouraged in asthmatics.[22]

The specific medical treatment recommended to patients with asthma depends on the severity of their illness and the frequency of their symptoms. Specific treatments for asthma are broadly classified as "Long-term control medications" (taken regularly to control symptoms and prevent asthma attacks), "Quick-relief" (rescue) medications," and "Biologics" (Taken with control medications to stop underlying biological responses causing inflammation in the lungs).[23]

Bronchodilators are recommended for short-term relief in all patients. For those who experience occasional attacks, no other medication is needed. For those with mild persistent disease (more than two attacks a week), low-dose inhaled glucocorticoids or alternatively, an oral leukotriene modifier (a drug that blocks the body's production of leukotrienes, a compound that contributes to the constriction of airways), a mast-cell stabilizer (which inhibits release of histamine, a compound involved in airway constriction), or theophylline (which relaxes bronchial smooth muscle) may be administered. For those who suffer daily attacks, a higher dose of glucocorticoid in conjunction with a long-acting inhaled β-2 agonist may be prescribed; alternatively, a leukotriene modifier or theophylline may substitute for the β-2 agonist. In severe asthmatics, oral glucocorticoids may be added to these treatments during severe attacks.

For those in whom exercise can trigger an asthma attack (exercise-induced asthma), higher levels of ventilation and cold, dry air tend to exacerbate attacks. For this reason, activities in which a patient breathes large amounts of cold air, such as skiing and running, tend to be worse for asthmatics, whereas swimming in an indoor, heated pool, with warm, humid air, is less likely to provoke a response.[19]

Alternative and complementary medicine

Many asthmatics, like those who suffer from other chronic disorders, use alternative treatments; surveys show that roughly 50 percent of asthma patients use some form of unconventional therapy.[24] These alternative treatments include the usage of vitamin C, vitamin D, or vitamin E for controlling asthma; "manual therapies" including osteopathic, chiropractic, physiotherapeutic and respiratory therapeutic maneuvers; and the Buteyko method, a Russian therapy based on breathing exercises.

There is little data to support the effectiveness of most of these therapies.

Emergency treatment

When an asthma attack is unresponsive to a patient's usual medication, other treatments are available to the physician or hospital:[25]

- oxygen to alleviate the hypoxia, aka oxygen depletion, (but not the asthma per se) that results from extreme asthma attacks;

- nebulized salbutamol or terbutaline (short-acting beta-2-agonists), often combined with ipratropium (an anticholinergic);

- systemic steroids, oral or intravenous (prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, dexamethasone, or hydrocortisone)

- other bronchodilators that are occasionally effective when the usual drugs fail:

- nonspecific beta-agonists, injected or inhaled (epinephrine, isoetharine, isoproterenol, metaproterenol);

- anticholinergics, IV or nebulized, with systemic effects (glycopyrrolate, atropine);

- methylxanthines (theophylline, aminophylline);

- inhalation anesthetics that have a bronchodilatory effect (isoflurane, halothane, enflurane);

- the dissociative anaesthetic ketamine, often used in endotracheal tube induction

- magnesium sulfate, intravenous; and

- intubation and mechanical ventilation, for patients in or approaching respiratory arrest.

Long-acting β2-agonists

Long-acting bronchodilators (LABD) are similar in structure to short-acting selective beta2-adrenoceptor agonists, but have much longer sidechains resulting in a 12-hour effect, and are used to give a smoothed symptomatic relief (used morning and night). While patients report improved symptom control, these drugs do not replace the need for routine preventers, and their slow onset means the short-acting dilators may still be required.

Currently available long-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonists include salmeterol, formoterol, bambuterol, and sustained-release oral albuterol. Combinations of inhaled steroids and long-acting bronchodilators are becoming more widespread; the most common combination currently in use is fluticasone/salmeterol (Advair in the United States, and Seretide in the United Kingdom).

Prevention medication

Current treatment protocols recommend prevention medications such as an inhaled corticosteroid, which helps to suppress inflammation and reduces the swelling of the lining of the airways, in anyone who has frequent (greater than twice a week) need of relievers or who has severe symptoms. If symptoms persist, additional preventive drugs are added until the asthma is controlled. With the proper use of prevention drugs, asthmatics can avoid the complications that result from overuse of relief medications.

Asthmatics sometimes stop taking their preventive medication when they feel fine and have no problems breathing. This often results in further attacks, and no long-term improvement.

Preventive agents include the following:

- Inhaled glucocorticoids are the most widely used of the prevention medications and normally come as brown inhaler devices (ciclesonide, beclomethasone, budesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone, mometasone, and triamcinolone).

Long-term use of corticosteroids can have many side effects including a redistribution of fat, increased appetite, blood glucose problems and weight gain. In particular high doses of steroids may cause osteoporosis. For this reasons inhaled steroids are generally used for prevention, as their smaller doses are targeted to the lungs unlike the higher doses of oral preparations. Nevertheless, patients on high doses of inhaled steroids may still require prophylactic treatment to prevent osteoporosis.

Deposition of steroids in the mouth may cause a hoarse voice or oral thrush (due to decreased immunity). This may be minimized by rinsing the mouth with water after inhaler use, as well as by using a spacer, which increases the amount of drug that reaches the lungs. - Leukotriene modifiers (montelukast, zafirlukast, pranlukast, and zileuton).

- Mast cell stabilizers (cromoglicate (cromolyn), and nedocromil).

- Antimuscarinics/anticholinergics (ipratropium, oxitropium, and tiotropium), which have a mixed reliever and preventer effect. (These are rarely used in preventive treatment of asthma, except in patients who do not tolerate beta-2-agonists.)

- Methylxanthines (theophylline and aminophylline), which are sometimes considered if sufficient control cannot be achieved with inhaled glucocorticoids and long-acting β-agonists alone.

- Antihistamines, often used to treat allergic symptoms that may underlie the chronic inflammation. In more severe cases, hyposensitization ("allergy shots") may be recommended.

- Omalizumab, an immunoglobulin E (IgE) blocker; this can help patients with severe allergic asthma that do not respond to other drugs. However, it is expensive and must be injected.

- Methotrexate is occasionally used in some difficult-to-treat patients.

- If chronic acid indigestion (Gastroesophageal reflux disease, GERD) contributes to a patient's asthma, it should also be treated, because it may prolong the respiratory problem.

Relief medication

Symptomatic control of episodes of wheezing and shortness of breath is generally achieved with fast-acting bronchodilators. These are typically provided in pocket-sized, metered-dose inhalers (MDIs).

In young sufferers, who may have difficulty with the coordination necessary to use inhalers, or those with a poor ability to hold their breath for 10 seconds after inhaler use (generally the elderly), an asthma spacer (see top image) is used. The spacer is a plastic cylinder that mixes the medication with air in a simple tube, making it easier for patients to receive a full dose of the drug and allows for the active agent to be dispersed into smaller, more fully inhaled bits.

A nebulizer—which provides a larger, continuous dose—can also be used. Nebulizers work by vaporizing a dose of medication in a saline solution into a steady stream of foggy vapor, which the patient inhales continuously until the full dosage is administered. There is no clear evidence, however, that they are more effective than inhalers used with a spacer. Nebulizers may be helpful to some patients experiencing a severe attack. Such patients may not be able to inhale deeply, so regular inhalers may not deliver medication deeply into the lungs, even on repeated attempts. Since a nebulizer delivers the medication continuously, it is thought that the first few inhalations may relax the airways enough to allow the following inhalations to draw in more medication.

Relievers include:

- Short-acting, selective beta2-adrenoceptor agonists, such as salbutamol (albuterol United States Adopted Name (USAN)), levalbuterol, terbutaline, and bitolterol, which normally come as blue inhaler devices.

Tremors, the major side effect, have been greatly reduced by inhaled delivery, which allows the drug to target the lungs specifically; oral and injected medications are delivered throughout the body. There may also be cardiac side effects at higher doses (due to Beta-1 agonist activity), such as elevated heart rate or blood pressure; with the advent of selective agents, these side effects have become less common. Patients must be cautioned against using these medicines too frequently, as with such use their efficacy may decline, producing desensitization resulting in an exacerbation of symptoms which may lead to refractory asthma and death. - Older, less selective adrenergic agonists, such as inhaled epinephrine and ephedrine tablets, are available over the counter in the US. Cardiac side effects occur with these agents at either similar or lesser rates to albuterol.[26] When used solely as a relief medication, inhaled epinephrine has been shown to be an effective agent to terminate an acute asthmatic exacerbation.[26] In emergencies, these drugs were sometimes administered by injection. Their use via injection has declined due to related adverse effects.

- Anticholinergic medications, such as ipratropium bromide may be used instead. They have no cardiac side effects and thus can be used in patients with heart disease; however, they take up to an hour to achieve their full effect and are not as powerful as the β2-adrenoreceptor agonists.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 J. Zhao, M. Takamura, A. Yamaoka, Y. Odajima, and Y. Iikura, Altered eosinophil levels as a result of viral infection in asthma exacerbation in childhood J Pediatr Allergy Immunol 13(1) (2002):47-50. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ C.M. Lilly, Diversity of asthma: Evolving concepts of pathophysiology and lessons from genetics J Allergy Clin Immunol 115(4 Suppl) (2005):S526-531. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ S.G. Marketos, and C.N. Ballas, Bronchial asthma in the medical literature of Greek antiquity J Asthma 19(4) (1982):263-269. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ F. Rosner, Moses Maimonides' treatise on asthma Thorax 36 (1981):245-251. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ Richard Varenchik, Study Links Air Pollution and Asthma California Air Resources Board, January 31, 2002. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Chronic respiratory diseases World Health Organization. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 J.M. Weiler, T. Layton, and M. Hunt, Asthma in United States Olympic athletes who participated in the 1996 Summer Games J Allergy Clin Immunol 102(5) (1998):722-726. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ I. Helenius, and T. Haahtela, Allergy and asthma in elite summer sport athletes J Allergy Clin Immunol 106(3) (2000):444-452. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ Lara Akinbami, Asthma Prevalence, Health Care Use and Mortality: United States, 2003-05 National Center for Health Statistics, November 6, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ J.J. Leggett, B.T. Johnston, M. Mills, J. Gamble, and L.G. Heaney, Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in difficult asthma. Chest 127(4) (2005): 1227-1231. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ K. Gazella, Breathing disorders during sleep are common among asthmatics, may help predict severe asthma Press Release, University of Michigan Health System, May 25, 2005. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 L. Maddox and D.A. Schwartz, The pathophysiology of asthma Annu. Rev. Med. 53 (2002):477-498. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ↑ C. Jenkins, J. Costello, and L. Hodge, Systematic review of prevalence of aspirin induced asthma and its implications for clinical practice British Medical Journal(BMJ) 328(7437) (2004):434. Retrieved March 7, 20201.

- ↑ B. Nemery, P.H. Hoet, and D. Nowak, Indoor swimming pools, water chlorination and respiratory health Eur Respir J 19(5) (2002):790-793. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ A. Szentivanyi, The Beta Adrenergic Theory of the atopic abnormality in asthma J. Allergy 42 (1968):203-232. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Blanca Camoretti-Mercado, and Richard F. Lockey, The β-adrenergic theory of bronchial asthma: 50 years later The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, July 22, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ H.H. Terttu, M. Leinonen, J. Nokso-Koivisto, T. Korhonen, R. Raty, Q. He, T. Hovi, J. Mertsola, A. Bloigu, P. Rytila, and P. Saikku, Non-random distribution of pathogenic bacteria and viruses in induced sputum or pharyngeal secretions of adults with stable asthma Thorax, March 3, 2006. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ P.A. Beckett and P.H. Howarth, Pharmacotherapy and airway remodelling in asthma? Thorax 58(2) (2003):163-174. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 J. Larry Jameson, Anthony Fauci, Dennis Kasper, Stephen Hauser, Dan Longo, and Joseph Loscalzo (eds.), Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20th 3d. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2018, ISBN 978-1259644030).

- ↑ N.C. Thomson, and M. Spears, The influence of smoking on the treatment response in patients with asthma Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 5(1) (2005):57-63. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ M.D. Eisner, E.H. Yelin, P.P. Katz, G. Earnest, and P.D. Blanc, Exposure to indoor combustion and adult asthma outcomes: environmental tobacco smoke, gas stoves, and woodsmoke Thorax 57(11) (2002):973-978. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Common Asthma Triggers Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Asthma medications: Know your options Mayo Clinic. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ P.D. Blanc, L. Trupin, G. Earnest, P.P. Katz, E.H. Yelin, and M.D. Eisner, Alternative therapies among adults with a reported diagnosis of asthma or rhinosinusitis: data from a population-based survey Chest 120(5) (2001):1461-1467. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ G.J. Rodrigo, C. Rodrigo, and J.B. Hall, Acute asthma in adults: a review Chest 125(3) (2004):1081-1102. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 L. Hendeles, P.L. Marshik, R. Ahrens, Y. Kifle, and J. Shuster, Response to nonprescription epinephrine inhaler during nocturnal asthma Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 95(6) (2005):530-534. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adams, Francis. The Asthma Sourcebook, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill Education, 2006. ISBN 978-0071476522

- Jameson, J. Larry, Anthony Fauci, Dennis Kasper, Stephen Hauser, Dan Longo, and Joseph Loscalzo (eds.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2018. ISBN 978-1259644030

- Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Professional Guide To Diseases, 10th ed. Wolters Kluwer, 2012. ISBN 978-1451144604

External links

All links retrieved August 19, 2023.

- Asthma World Health Organization

- Asthma MedLinePlus

- Asthma Overview – Taking Control of This Chronic Condition Today

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.