ADHD

| Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | |

| |

| Symptoms | Inattention, carelessness, hyperactivity, executive dysfunction, disinhibition, emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, impaired working memory |

|---|---|

| Usual onset | Symptoms should onset in developmental period unless ADHD occurred after traumatic brain injury (TBI). |

| Causes | Genetic (inherited, de novo) and to a lesser extent, environmental factors (exposure to biohazards during pregnancy, traumatic brain injury) |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after other possible causes have been ruled out |

| Differential diagnosis | Normally active child, bipolar disorder, cognitive disengagement syndrome, conduct disorder, major depressive disorder, autism spectrum disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, learning disorder, intellectual disability, anxiety disorder, borderline personality disorder, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder |

| Treatment | Psychotherapy, lifestyle changes, medication |

| Medication | CNS stimulants (methylphenidate, amphetamine), non-stimulants (atomoxetine, viloxazine), alpha-2a agonists (guanfacine XR, clonidine XR) |

| Frequency | 0.8–1.5% |

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by executive dysfunction occasioning symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity and emotional dysregulation that are excessive and pervasive, impairing in multiple contexts, and otherwise age-inappropriate. Although people with ADHD struggle to sustain attention on tasks that entail delayed rewards or consequences, they are often able to maintain an unusually prolonged and intense level of attention for tasks they do find interesting or rewarding; this is known as hyperfocus.

ADHD, its diagnosis, and its treatment have been considered controversial since the 1970s, with issues including over-diagnosis, use of stimulants as treatment for children, as well as disagreements on the nature of the disorder. ADHD is now a well-validated clinical diagnosis in children and adults, and the debate in the scientific community mainly centers on how it is diagnosed and treated. ADHD management recommendations usually involve some combination of medications, counseling, and lifestyle changes. For the majority of individuals, such treatment enables them to live productive and fulfilling lives.

History

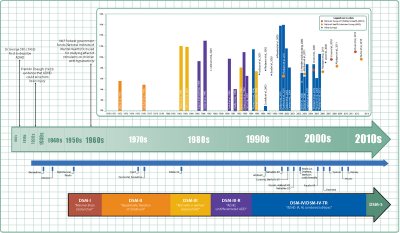

Hyperactivity has long been part of the human condition. Sir Alexander Crichton described "mental restlessness" in his book An Inquiry Into The Nature And Origin Of Mental Derangement written in 1798. He made observations about children showing signs of being inattentive and having the "fidgets."[2]

The first clear description of ADHD is credited to George Still in 1902 during a series of lectures he gave to the Royal College of Physicians of London.[3] He noted that both nature and nurture could be influencing this disorder.

The terminology used to describe the condition has changed over time. Prior to the DSM, terms included minimal brain damage in the 1930s.[4] Other terms include: minimal brain dysfunction in the DSM-I (1952), hyperkinetic reaction of childhood in the DSM-II (1968), and attention-deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity in the DSM-III (1980).[1] In 1987, this was changed to Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the DSM-III-R, and in 1994 the DSM-IV in split the diagnosis into three subtypes: ADHD inattentive type, ADHD hyperactive-impulsive type, and ADHD combined type.[5] These terms were kept in the DSM-5 in 2013[6] and in the DSM-5-TR in 2022.[7]

Signs and symptoms

ADHD is characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and emotional dysregulation that are excessive and pervasive, impairing in multiple contexts, and otherwise age-inappropriate.[6][7][8] The signs and symptoms can be difficult to define, as it is hard to draw a line at where normal levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity end and significant levels requiring interventions begin.[9]

In children, problems paying attention may result in poor school performance. ADHD is associated with other neurodevelopmental and mental disorders as well as some non-psychiatric disorders, which can cause additional impairment, especially in modern society. Although people with ADHD struggle to sustain attention on tasks that entail delayed rewards or consequences, they are often able to maintain an unusually prolonged and intense level of attention for tasks they do find interesting or rewarding; this is known as hyperfocus.

Inattention, hyperactivity (restlessness in adults), disruptive behavior, and impulsivity are common in ADHD. Academic difficulties are frequent as are problems with relationships.[10] Elevated accident-proneness has been found in ADHD patients.[11]

Significantly more males than females are diagnosed with ADHD. It has been suggested that this could be due to gender differences in how ADHD presents. Boys and men tend to display more hyperactive and impulsive behavior while girls and women are more likely to have inattentive symptoms. There are also gender differences in how these symptomatic and behavioral differences are manifested.[12]

Symptoms are expressed differently and more subtly as the individual ages:

Whereas the core symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention, are well characterised in children, these symptoms may have different and more subtle expressions in adult life. [13]

Hyperactivity tends to become less overt with age and turns into inner restlessness, difficulty relaxing or remaining still, talkativeness or constant mental activity in teens and adults with ADHD:

For instance, where children with ADHD may run and climb excessively, or have difficulty in playing or engaging quietly in leisure activities, adults with ADHD are more likely to experience inner restlessness, inability to relax, or over talkativeness. Hyperactivity may also be expressed as excessive fidgeting, the inability to sit still for long in situations when sitting is expected (at the table, in the movie, in church or at symposia), or being on the go all the time. ... For example, physical overactivity in children could be replaced in adulthood by constant mental activity, feelings of restlessness and difficulty engaging in sedentary activities.[13]

Impulsivity in adulthood may appear as thoughtless behavior, impatience, irresponsible spending and sensation-seeking behaviors, while inattention may appear as becoming easily bored, difficulty with organization, remaining on task and making decisions, and sensitivity to stress:

Impulsivity may be expressed as impatience, acting without thinking, spending impulsively, starting new jobs and relationships on impulse, and sensation seeking behaviours. ... Inattention often presents as distractibility, disorganization, being late, being bored, need for variation, difficulty making decisions, lack of overview, and sensitivity to stress.[13]

Although not listed as an official symptom for this condition, emotional dysregulation or mood lability is generally understood to be a common symptom of ADHD.[13]

Diagnosis

ADHD is diagnosed by an assessment of a person's behavioral and mental development, including ruling out the effects of drugs, medications, and other medical or psychiatric problems as explanations for the symptoms. ADHD diagnosis often takes into account feedback from parents and teachers.[14]

In North America and Australia, the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (currently DSM-5) criteria are used for diagnosis, while European countries usually use the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (currently ICD-11). ADHD is alternately classified as neurodevelopmental disorder[15] or a disruptive behavior disorder along with Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), Conduct disorder (CD), and antisocial personality disorder.[16]

Self-rating scales, such as the ADHD rating scale and the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic rating scale, are used in the screening and evaluation of ADHD.[17]

Classification

ADHD is divided into three primary presentations:

- predominantly inattentive (ADHD-PI or ADHD-I)

- predominantly hyperactive-impulsive (ADHD-PH or ADHD-HI)

- combined presentation (ADHD-C).

The table below lists the symptoms for ADHD-I and ADHD-HI from the two major classification systems. Symptoms which can be better explained by another psychiatric or medical condition which an individual has are not considered to be a symptom of ADHD for that person.

| Presentations | DSM-5[6] and DSM-5-TR[7] symptoms | ICD-11[8] symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Inattention | Six or more of the following symptoms in children, and five or more in adults, excluding situations where these symptoms are better explained by another psychiatric or medical condition:

|

Multiple symptoms of inattention that directly negatively impact occupational, academic or social functioning. Symptoms may not be present when engaged in highly stimulating tasks with frequent rewards. Symptoms are generally from the following clusters:

The individual may also meet the criteria for hyperactivity-impulsivity, but the inattentive symptoms are predominant. |

| Hyperactivity-Impulsivity | Six or more of the following symptoms in children, and five or more in adults, excluding situations where these symptoms are better explained by another psychiatric or medical condition:

|

Multiple symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity that directly negatively impact occupational, academic or social functioning. Typically, these tend to be most apparent in environments with structure or which require self-control. Symptoms are generally from the following clusters:

The individual may also meet the criteria for inattention, but the hyperactive-impulsive symptoms are predominant. |

| Combined | Meet the criteria for both inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive ADHD. | Criteria are met for both inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive ADHD, with neither clearly predominating. |

DSM-5

As with many other psychiatric disorders, a formal diagnosis should be made by a qualified professional based on a set number of criteria. In the United States, these criteria are defined by the American Psychiatric Association in the DSM. Based on the DSM-5 criteria published in 2013 and the DSM-5-TR criteria published in 2022, there are three presentations of ADHD:

- ADHD, predominantly inattentive type, presents with symptoms including being easily distracted, forgetful, daydreaming, disorganization, poor concentration, and difficulty completing tasks.

- ADHD, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type, presents with excessive fidgeting and restlessness, hyperactivity, and difficulty waiting and remaining seated.

- ADHD, combined type, a combination of the first two presentations.

Symptoms must be present for six months or more to a degree that is much greater than others of the same age. This requires at least six symptoms of either inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity for those under 17 and at least five symptoms for those 17 years or older. The symptoms must be present in at least two settings (such as social, school, work, or home), and must directly interfere with or reduce quality of functioning.[6] Additionally, several symptoms must have been present before age twelve.[7]

The DSM-5 and the DSM-5-TR also provide two diagnoses for individuals who have symptoms of ADHD but do not entirely meet the requirements. Other Specified ADHD allows the clinician to describe why the individual does not meet the criteria, whereas Unspecified ADHD is used where the clinician chooses not to describe the reason.

ICD-11

In the eleventh revision of the World Health Organization's ICD-11, the disorder is classified as Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (code 6A05). The defined subtypes are similar to those of the DSM-5: predominantly inattentive presentation (6A05.0); predominantly hyperactive-impulsive presentation(6A05.1); combined presentation (6A05.2). The ICD-11 also includes the two residual categories for individuals who do not entirely match any of the defined subtypes: other specified presentation (6A05.Y) where the clinician includes detail on the individual's presentation; and presentation unspecified (6A05.Z) where the clinician does not provide detail.[8]

Adults

Adults with ADHD are diagnosed under the same criteria as children, including that their signs must have been present by the age of six to twelve. The individual is the best source for information in diagnosis, however others may provide useful information about the individual's symptoms currently and in childhood; a family history of ADHD also adds weight to a diagnosis.

While the core symptoms of ADHD are similar in children and adults, they often present differently: Excessive physical activity seen in children may present as feelings of restlessness and constant mental activity in adults. Adults with ADHD may start relationships impulsively, display sensation-seeking behaviour, and be short-tempered. Addictive behavior such as substance abuse and gambling are common.[13]

Differential diagnosis

The DSM provides potential differential diagnoses – potential alternate explanations for specific symptoms. Assessment and investigation of clinical history determines which is the most appropriate diagnosis. The DSM-5 suggests ODD, intermittent explosive disorder, and other neurodevelopmental disorders (such as stereotypic movement disorder and Tourette's disorder), in addition to specific learning disorder, intellectual developmental disorder, ASD, reactive attachment disorder, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, substance use disorder, personality disorders, psychotic disorders, medication-induced symptoms, and neurocognitive disorders. Many but not all of these are also common comorbidities of ADHD.[6] The DSM-5-TR also suggests post-traumatic stress disorder.[7]

Primary sleep disorders may affect attention and behavior and the symptoms of ADHD may affect sleep. It is thus recommended that children with ADHD be regularly assessed for sleep problems. Sleepiness in children may result in symptoms ranging from the classic ones of yawning and rubbing the eyes, to hyperactivity and inattentiveness. Obstructive sleep apnea can also cause ADHD-type symptoms.

Comorbidities

Psychiatric

Various neurodevelopmental conditions are common comorbidities. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and ADHD can be diagnosed in the same person.[7] ADHD is not considered a learning disability, but it very frequently causes academic difficulties and Intellectual disabilities.[7]

ADHD is often comorbid with disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), characterized by angry or irritable mood, argumentative or defiant behavior and vindictiveness which are age-inappropriate, occurs in about 25 percent of children with an inattentive presentation and 50 percent of those with a combined presentation. Conduct disorder (CD), characterized by aggression, destruction of property, deceitfulness, theft and violations of rules, occurs in about 25 percent of adolescents with ADHD.[7]

Anxiety disorders have been found to occur more commonly in the ADHD population, as have mood disorders (especially bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder).

Sleep disorders and ADHD commonly co-exist. However, they can also occur as a side effect of medications used to treat ADHD.

There are other psychiatric conditions which are often co-morbid with ADHD, such as substance use disorders, commonly seen with alcohol or cannabis.[13] Other psychiatric conditions include reactive attachment disorder and eating disorders.

Trauma

ADHD, trauma, and Adverse Childhood Experiences are also comorbid, which could in part be potentially explained by the similarity in presentation between different diagnoses. The symptoms of ADHD and PTSD can have significant behavioral overlap—in particular, motor restlessness, difficulty concentrating, distractibility, irritability/anger, emotional constriction or dysregulation, poor impulse control, and forgetfulness are common in both.

Non-psychiatric

Some non-psychiatric conditions are also comorbidities of ADHD. This includes epilepsy, a neurological condition characterized by recurrent seizures. There are well established associations between ADHD and obesity, asthma and sleep disorders. Children with ADHD have a higher risk for migraine headaches, but have no increased risk of tension-type headaches. In addition, children with ADHD may also experience headaches as a result of medication.

Suicide risk

Systematic reviews conducted in 2017 and 2020 found strong evidence that ADHD is associated with increased suicide risk across all age groups, as well as growing evidence that an ADHD diagnosis in childhood or adolescence represents a significant future suicidal risk factor. However, the relationship between ADHD and suicidal spectrum behaviors remains unclear. There is no clear data on whether there is a direct relationship between ADHD and suicidality, or whether ADHD increases suicide risk through comorbidities.[18]

Causes

The precise causes of ADHD are unknown in the majority of cases. For most people with ADHD, many genetic and environmental risk factors accumulate to cause the disorder. The environmental risks for ADHD most often exert their influence in the early prenatal period.

Genetics

Family, twin, and adoption studies show that ADHD runs in families, with an average heritability of 74 percent.[19] The siblings of children with ADHD are three to four times more likely to develop the disorder than siblings of children without the disorder.[20]

There are multiple gene variants which each slightly increase the likelihood of a person having ADHD; it is polygenic and arises through the combination of many gene variants which each have a small effect.[19]

For genetic variation to be used as a tool for diagnosis, more validating studies need to be performed.

Environment

In addition to genetics, environmental factors might play a role in ADHD development.causing ADHD.[21]

Environmental risk factors that have been identified as risk factors for ADHD include:[22]

- Maternal smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug use during pregnancy

- Premature birth, or a low birth weight

- Environmental toxins, including exposure to lead and pesticides, and air pollution

- Some illnesses, such as bacterial diseases (such as encephalitis)

Studies have shown a relationship between media use and ADHD-related behaviors.[23] In October 2018, PNAS USA published a systematic review of four decades of research on the relationship between children and adolescents' screen media use and ADHD-related behaviors and concluded that a statistically small relationship between children's media use and ADHD-related behaviors exists.[24]

Pathophysiology

Brain structure

Once neuroimaging studies became possible, studies conducted in the 1990s provided support for the pre-existing theory that neurological differences - particularly in the frontal lobes - were involved in ADHD.

In children with ADHD, there is a general reduction of volume in certain brain structures, with a proportionally greater decrease in the volume in the left-sided prefrontal cortex.[25] Other brain structures in the prefrontal-striatal-cerebellar and prefrontal-striatal-thalamic circuits have also been found to differ between people with and without ADHD, while the subcortical volumes of the accumbens, amygdala, caudate, hippocampus, and putamen appears smaller in individuals with ADHD compared with controls.[26] Structural MRI studies have also revealed differences in white matter, with marked differences in inter-hemispheric asymmetry between ADHD and typically developing youths.[27]

Function MRI (fMRI) studies have revealed a number of differences between ADHD and control brains. Mirroring what is known from structural findings, fMRI studies have shown evidence for a higher connectivity between subcortical and cortical regions, such as between the caudate and prefrontal cortex. The degree of hyperconnectivity between these regions correlated with the severity of inattention or hyperactivity [28]

Executive function

The symptoms of ADHD arise from a deficiency in certain executive functions - the cognitive processes that are required to successfully select and monitor behaviors that facilitate the attainment of one's chosen goals. The executive function impairments that occur in ADHD individuals result in problems with staying organized, time keeping, excessive procrastination, maintaining concentration, paying attention, ignoring distractions, regulating emotions, and remembering details. Due to the rates of brain maturation and the increasing demands for executive control as a person gets older, ADHD impairments may not fully manifest themselves until adolescence or even early adulthood.[29] Conversely, brain maturation trajectories, potentially exhibiting diverging longitudinal trends in ADHD, may support a later improvement in executive functions after reaching adulthood.

ADHD has also been associated with motivational deficits in children. Children with ADHD often find it difficult to focus on long-term over short-term rewards, and exhibit impulsive behavior for short-term rewards.[30]

Paradoxical reaction

Another sign of the structurally altered signal processing in the central nervous system in this group of people is the conspicuously common Paradoxical reaction. These are unexpected reactions to a chemical substance, such as a medical drug, that is opposite to what would usually be expected, or an otherwise significantly different reactions. They may occur with neuroactive substances such as local anesthetic at the dentist, sedative, caffeine, antihistamine, weak neuroleptics, and central and peripheral painkillers.

Management

While there is no cure for ADHD, it is possible to reduce symptoms and improve functioning. ADHD management recommendations vary and usually involve some combination of medications, counseling, education or training, and lifestyle changes.[31] The British guideline emphasizes environmental modifications and education about ADHD for individuals and carers as the first response. If symptoms persist, parent-training, medication, or psychotherapy (especially cognitive behavioral therapy) can be recommended based on age.[32] Canadian and American guidelines recommend medications and behavioral therapy together, except in preschool-aged children for whom the first-line treatment is behavioral therapy alone.[33] [34]

Behavioral therapies

Behavioral therapies are the recommended first-line treatment in those who have mild symptoms or who are preschool-aged, and there is strong evidence for their effectiveness. Psychological therapies used include: psychoeducational input, behavior therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, family therapy, school-based interventions, social skills training, behavioral peer intervention, organization training, and parent management training.[32]

Parent training may improve a number of behavioral problems including oppositional and non-compliant behaviors. Social skills training, behavioral modification, and medication may have some limited beneficial effects in peer relationships.

Medication

The use of stimulants to treat ADHD was first described in 1937: Charles Bradley gave "problem" children Benzedrine to alleviate headaches and found it unexpectedly improved their school performance, social interactions, and emotional responses. Although Bradley's studies were basically ignored for nearly 25 years, they were an important precursor to studies of amphetamines like Ritalin and their use in managing ADHD.[35]

Stimulants

Methylphenidate and amphetamine or its derivatives are often first-line treatments for ADHD.[36] Studies show that amphetamine is slightly-to-modestly more effective than methylphenidate at reducing symptoms.[37]

Non-stimulants

Two non-stimulant medications, atomoxetine and viloxazine, are approved by the FDA and in other countries for the treatment of ADHD. They produce comparable efficacy and tolerability to methylphenidate, but all three tend to be modestly more tolerable and less effective than amphetamines.

Two alpha-2a agonists, extended-release formulations of guanfacine and clonidine, are approved by the FDA and in other countries for the treatment of ADHD (effective in children and adolescents but effectiveness has still not been shown for adults). They appear to be modestly less effective than the stimulants (amphetamine and methylphenidate) and non-stimulants (atomoxetine and viloxazine) at reducing symptoms, but can be useful alternatives or used in conjunction with a stimulant.[38]

Exercise

Regular physical exercise, particularly aerobic exercise, is an effective add-on treatment for ADHD in children and adults, particularly when combined with stimulant medication. The long-term effects of regular aerobic exercise in ADHD individuals include better behavior and motor abilities, improved executive functions (including attention, inhibitory control, and planning, among other cognitive domains), faster information processing speed, and better memory. Parent-teacher ratings in response to regular aerobic exercise include: better overall function, reduced ADHD symptoms, better self-esteem, reduced levels of anxiety and depression, fewer somatic complaints, better academic and classroom behavior, and improved social behavior.[39]

Prognosis

ADHD is a life-long condition, but for many it is possible to manage symptoms effectively, thus not meet the criteria for ADHD in adulthood. The long-term outlook (prognosis) of ADHD depends on whether treatment is received early on. With behavior therapy and/or medication, most children go on to live healthy lives. However, without treatment, people with ADHD may experience lifelong complications.[40]

Controversy

ADHD, its diagnosis, and its treatment have been controversial since the 1970s. Controversies involve clinicians, teachers, policymakers, parents, and the media.

Positions range from the view that ADHD is a valid psychiatric disorder characterized by behavioral problems,[41] possibly a genetic condition,[42] to blaming parents for poorly disciplining their children or feeding them too much sugar,[42] or regarding it as one end of a normal continuum of a set of centrally important cognitive and behavioral traits, and thus "treatment" being understood as enhancing performance to improve functioning rather than correcting the effects of a disorder.[43]

Other areas of controversy include the use of stimulant medications in children, the method of diagnosis, and the possibility of overdiagnosis.[44] On the other hand, a 2014 peer-reviewed medical literature review indicated that ADHD is under-diagnosed in adults.[45]

Numerous factors intrinsic to a child or youth can affect their diagnosis of ADHD including, gender, age, race, and socioeconomic status, in addition to the severity of symptoms. With widely differing rates of diagnosis across countries, states within countries, races, and ethnicities, some suspect factors other than the presence of the symptoms of ADHD are playing a role in diagnosis, such as cultural norms. Multiple individuals have significant impact in the identification and diagnosis of ADHD including parents, healthcare providers, and teachers, and aspects of the environment. Their different cultural and ethnic backgrounds may lead to different views and perceptions of behavioral norms and when to consider behavior inappropriate or indicative of a clinical disorder such as ADHD.[46]

ADHD is now a well-validated clinical diagnosis in children and adults, and debate in the scientific community mainly concerns how it is diagnosed and treated.[47]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 ADHD Throughout the Years Center For Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ↑ Sir Alexander Crichton, An Inquiry Into The Nature And Origin Of Mental Derangement (Legare Street Press, 2022 (original 1798), ISBN 978-1017488913).

- ↑ George Still, The Goulstonian Lectures on some Abnormal Psychical Conditions in Children The Lancet 159(4102) (April 12, 1902):1008-1013. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ↑ Margaret Weiss, Lily Trokenberg Hechtman, and Gabrielle Weiss, ADHD in Adulthood: A Guide to Current Theory, Diagnosis, and Treatment (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0801868221).

- ↑ J. Gordon Millichap, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook (Springer, 2009, ISBN 978-1441913968).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013, ISBN 978-0890425541).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition Text Revision: DSM-5-TR (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2022, ISBN 0890425760).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 6A05 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ICD-11. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ↑ J. Russell Ramsay and Anthony L. Rostain, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Adult ADHD: An Integrative Psychosocial and Medical Approach (Routledge, 2007, ISBN 978-0415955010).

- ↑ What is ADHD? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- ↑ Nathalie Brunkhorst-Kanaan, Berit Libutzki, Andreas Reif, Henrik Larsson, Rhiannon V. McNeill, and Sarah Kittel-Schneider, ADHD and accidents over the life span – A systematic review Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews (125) (2021):582–591. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ↑ Female vs Male ADHD The ADHD Centre (December 21, 2022). Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHD BMC Psychiatry 10(67) (2010). Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ↑ Mina K. Dulcan, Rachel R. Ballard, Poonam Jha, and Julie M. Sadhu, Concise Guide to Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2017, ISBN 978-1615370788).

- ↑ Caroline S. Clauss-Ehlers, Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural School Psychology (Springer, 2010, ISBN 978-0387717982).

- ↑ Jerry M. Wiener and Mina K. Dulcan (eds.), Textbook Of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-1585620579).

- ↑ Eric A. Youngstrom, Mitchell J. Prinstein, Eric J. Mash, and Russell A. Barkley (eds.), Assessment of Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence (The Guilford Press, 2020, ISBN 978-1462543632).

- ↑ P. Garas and J. Balazs, Long-Term Suicide Risk of Children and Adolescents With Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder-A Systematic Review, Frontiers in Psychiatry 11 (December 21, 2020):557909.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Stephen V. Faraone and Henrik Larsson, Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder Molecular Psychiatry 24(4) (2019):562–575. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Susan Nolen-Hoeksema, Abnormal Psychology (McGraw Hill, 2022, ISBN 978-1265237769).

- ↑ Research on ADHD Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Exploring the Links Between ADHD and Environmental Factors The ADHD Centre (July 13, 2023). Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ S.W.C. Nikkelen, P.M. Valkenburg, Mariëtte Huizinga, and B.J. Bushman, Media use and ADHD-related behaviors in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis Developmental Psychology 50(9) (2014):2228–2241. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Ine Beyens, Patti M, Valkenburg, and Jessica Taylor Piotrowski, Screen media use and ADHD-related behaviors: Four decades of researchProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS USA) 115(40) (October 2, 2018):9875–9881. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Amy L Krain and F. Xavier Castellanos, Brain development and ADHD Clinical Psychology Review 26(4) (August 2005):433–444. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Martine Hoogman et al., Subcortical brain volume differences in participants with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: a cross-sectional mega-analysis Lancet Psychiatry 4(4) (April 2017):310-319. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ P.K. Douglas et al., Hemispheric brain asymmetry differences in youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder Neuroimage Clin. 18 (February 2018):744–752. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Stefano Damiani et al., Beneath the surface: hyper-connectivity between caudate and salience regions in ADHD fMRI at rest European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 30(4) (April 2021):619–631. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Thomas E. Brown, ADD/ADHD and Impaired Executive Function in Clinical Practice Current Psychiatry Reports 10(5) (October 2008):407–411. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Vania Modesto-Lowe, Margaret Chaplin, Victoria Soovajian, and Andrea Meyer, Are motivation deficits underestimated in patients with ADHD? A review of the literature Postgraduate Medicine 125(4) (July 2013):47–52. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), September 13, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Canadian ADHD Practice Guidelines Canadian Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Resource Alliance (CADDRA), 2010. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ ADHD Treatment Recommendations Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Madeleine P. Strohl, Bradley's Benzedrine studies on children with behavioral disorders Yale J Biol Med. 84(1) (March 2011):27-33. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Ole Jakob Storebø et al., Methylphenidate for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3(3) (March 27, 2023:CD009885. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Stephen V. Faraone, Joseph Biederman, and Christine Roe, Efficacy, Acceptability, and Tolerability of Lisdexamfetamine, Mixed Amphetamine Salts, Methylphenidate, and Modafinil in the Treatment of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Annals of Pharmacotherapy 53(2) (2002):121–133. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Sharon B. Wigal, Efficacy and safety limitations of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder pharmacotherapy in children and adults CNS Drugs (23)(Suppl 1) (2009):21–31. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Anne E Den Heijer et al, Sweat it out? The effects of physical exercise on cognition and behavior in children and adults with ADHD: a systematic literature review Journal of Neural Transmission 124(Suppl 1) (2017):3–26. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Stephen V. Faraone, The scientific foundation for understanding attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as a valid psychiatric disorder European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 14(1) (February 2005):1–10. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Sarah Boseley, Hyperactive children may suffer from genetic disorder, says study The Guardian (September 29, 2010). Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Ralph Lewis, Is ADHD a Real Disorder or One End of a Normal Continuum? Psychology Today (January 6, 2021). Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Eileen Cormier, Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review and update Journal of Pediatric Nursing 23(5) (October 2008):345-357. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Ylva Ginsberg, Javier Quintero,Ernie Anand, Marta Casillas, and Himanshu P. Upadhyaya, Underdiagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Adult Patients: A Review of the Literature The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders 16(3) (2014). Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Alaa M. Hamed, Aaron J. Kauer, and Hanna E. Stevens, Why the Diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Matters Frontiers in Psychiatry 6 (November 26, 2015). Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ↑ Larry B. Silver, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Clinical Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment for Health and Mental Health Professionals (American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-1585621316).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. ISBN 978-0890425541

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition Text Revision: DSM-5-TR. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2022. ISBN 0890425760

- Clauss-Ehlers, Caroline S. Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural School Psychology. Springer, 2010. ISBN 978-0387717982

- Crichton, Sir Alexander. An Inquiry Into The Nature And Origin Of Mental Derangement. Legare Street Press, 2022 (original 1798). ISBN 978-1017488913

- Dulcan, Mina K., Rachel R. Ballard, Poonam Jha, and Julie M. Sadhu. Concise Guide to Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2017. ISBN 978-1615370788

- Millichap, J. Gordon. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook. Springer, 2009. ISBN 978-1441913968

- Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan. Abnormal Psychology. McGraw Hill, 2022. ISBN 978-1265237769

- Ramsay, J. Russell, and Anthony L. Rostain. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Adult ADHD: An Integrative Psychosocial and Medical Approach. Routledge, 2007. ISBN 978-0415955010

- Silver, Larry B. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Clinical Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment for Health and Mental Health Professionals. American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2003. ISBN 978-1585621316

- Weiss, Margaret, Lily Trokenberg Hechtman, and Gabrielle Weiss. ADHD in Adulthood: A Guide to Current Theory, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0801868221

- Wiener, Jerry M., and Mina K. Dulcan (eds.). Textbook Of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003. ISBN 978-1585620579

- Youngstrom, Eric A., Mitchell J. Prinstein, Eric J. Mash, and Russell A. Barkley (eds.). Assessment of Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. The Guilford Press, 2020. ISBN 978-1462543632

External links

All links retrieved January 22, 2024.

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

- Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- What is ADHD? American Psychiatric Association

- Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Mayo Clinic

- Everything You Need to Know About ADHD HealthLine

- Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Children Johns Hopkins Medicine

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Cleveland Clinic

- 6A05 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ICD-11

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.