Warring States Period

The Warring States period covers the period from sometime in the fifth century B.C.E. to the unification of China by the Qin dynasty in 221 B.C.E. It is nominally considered to be the second part of the Eastern Zhou dynasty, following the Spring and Autumn period, although the Zhou dynasty itself ended in 256 B.C.E., 35 years earlier than the end of the Warring States period. Like the Spring and Autumn Period, the king of Zhou acted merely as a figurehead.

The name “Warring States period” was derived from the Record of the Warring States compiled in early Han dynasty. The date for the beginning of the Warring States Period is somewhat in dispute. While it is frequently cited as 475 B.C.E. (following the Spring and Autumn Period), 403 B.C.E.—the date of the tripartition of the Jin state—is also sometimes considered as the beginning of the period.

Chinese polity developed a bias towards centralization and unity, which can be traced from this period. On the one hand, it was a time of rivalry between competing states. On the other, as states consolidated their rule, they annexed smaller dukedoms. Confucius had already established unity as an ideal, and the end of this period saw the ascendancy of the Qin dynasty and China as a single imperial state.

Characterizations of the period

The rise of kingdom

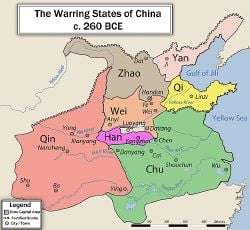

The Warring States period, in contrast to the Spring and Autumn period, was a period when regional warlords annexed smaller states around them and consolidated their rule. The process began in the Spring and Autumn period, and by the third century B.C.E., seven major states had risen to prominence. These Seven Warring States (Zhànguó Qīxióng, literally "Seven Hegemonial among the Warring States"), were Qi, the Chu, the Yan, the Han, the Zhao, the Wei and the Qin. Another sign of this shift in power was a change in title: warlords still considered themselves dukes of the Zhou dynasty king; but now the warlords began to call themselves kings (pinyin: wáng), meaning they were equal to the Zhou king.

The Cultural Sphere

The Warring States period saw the proliferation of iron working in China, replacing bronze as the dominant metal used in warfare. Areas such as Shu (modern Sichuan) and Yue (modern Zhejiang) were also brought into the Chinese cultural sphere during this time. Walls built by the states to keep out northern nomadic tribes and each other were the precursors of the Great Wall of China. Different philosophies developed into the Hundred Schools of Thought, including Confucianism (elaborated by Mencius), Daoism (elaborated by Zhuangzi), Legalism (formulated by Han Feizi) and Mohism (formulated by Mozi). Trade also became important, and some merchants had considerable power in politics.

Military tactics also changed. Unlike the Spring and Autumn period, most armies in the Warring States period made combined use of infantry and cavalry, and the use of chariots gradually fell into disfavor. Thus from this period on, the nobles in China remained a literate rather than warrior class, as the kingdoms competed by throwing masses of soldiers against each other. Arms of soldiers gradually changed from bronze to unified iron arms. Dagger-axes were an extremely popular weapon in various kingdoms, especially for the Qin who produced 18-foot-long pikes.

This was also around the time the legendary military strategist Sun Zi wrote The Art of War which is recognized today as the most influential, and oldest known military strategy guide. Along with this are other military writings that make up the Seven Military Classics of ancient China: Jiang Ziya's Six Secret Teachings, The Methods of the Sima, Sun Zi's The Art of War, Wu Qi, Wei Liaozi, Three Strategies of Huang Shigong, and The Questions and Replies of Tang Taizong and Li Weigong (the last being made about eight hundred years after this era ended). Once China was unified, these seven military classics were locked away and access was restricted due to their tendency to promote revolution.

Partition of Jin

In the Spring and Autumn period, the state of Jin was arguably the most powerful state in China. However, near the end of the Spring and Autumn period, the power of the ruling family weakened, and Jin gradually came under the control of six large families. By the beginning of the Warring States period, after numerous power struggles, there were four families left: the Zhi family, the Wei family, the Zhao family, and the Han family, with the Zhi family being the dominant power in Jin. Zhi Yao, the last head of the Zhi family, attempted a coalition with the Wei family and the Han family to destroy the Zhao family. However, because of Zhi Yao's arrogance and disrespect towards the other families, the Wei family and Han family secretly allied with the Zhao family and the three families launched a surprise attack at Jinyang, which was beseiged by Zhi Yao at the time, and annihilated the Zhi.

In 403 B.C.E., the three major families of Jin, with the approval of the Zhou king, partitioned Jin into three states, which was historically known as “The Partition of Jin of the Three Families.” The new states were Han, Zhao, and Wei. The three family heads were given the title of marquis, and because the three states were originally part of Jin, they are also referred to as the “Three Jins.” The state of Jin continued to exist with a tiny piece of territory until 376 B.C.E. when the rest of the territory was partitioned by the three Jins.

Change of Government in Qi

In 389 B.C.E., the Tian family seized control of the state of Qi and was given the title of duke. The old Jiang family's Qi continued to exist with a small piece of territory until 379 B.C.E., when it was finally absorbed into Tian family's state of Qi.

Early strife in the Three Jins, Qi, and Qin

In 371 B.C.E., Marquess Wu of Wei died without specifying a successor, causing Wei to fall into an internal war of succession. After three years of civil war, Zhao and Han, sensing an opportunity, invaded Wei. On the verge of conquering Wei, the leaders of Zhao and Han fell into disagreement on what to do with Wei and both armies mysteriously retreated. As a result, King Hui of Wei (still a marquess at the time) was able to ascend onto the throne of Wei.

In 354 B.C.E., King Hui of Wei initiated a large scale attack at Zhao, which some historians believe was to avenge the earlier near destruction of Wei. By 353 B.C.E., Zhao was losing the war badly, and one of their major cities — Handan, a city that would eventually become Zhao's capital — was being besieged. As a result, neighbouring Qi decided to help Zhao. The strategy Qi used, suggested by the famous tactician Sun Bin, a descendant of Sun Zi, who at the time was the Qi army advisor, was to attack Wei's territory while the main Wei army was busy laying siege to Zhao, forcing Wei to retreat. The strategy was a success; the Wei army hastily retreated, and encountered the Qi midway, culminating into the Battle of Guiling where Wei was decisively defeated. The event spawned the idiom "Surrounding Wei to save Zhao," which is still used in modern Chinese to refer to attacking an enemy's vulnerable spots in order to relieve pressure being applied by that enemy upon an ally.

In 341 B.C.E., Wei attacked Han, and Qi interfered again. The two generals from the previous Battle of Guiling met again, and due to the brilliant strategy of Sun Bin, Wei was again decisively defeated at the Battle of Maling.

The situation for Wei took an even worse turn when Qin, taking advantage of Wei series of defeats by Qi, attacked Wei in 340 B.C.E. under the advice of famous Qin reformer Shang Yang. Wei was devastatingly defeated and was forced to cede a large portion of its territory to achieve a truce. This left their capital Anyi vulnerable, so Wei was also forced to move their capital to Daliang.

After these series of events, Wei became severely weakened, and the Qi and Qin states became the two dominant states in China.

Shang Yang's reforms in Qin

Around 359 B.C.E., Shang Yang, a minister of the Qin, initiated a series of reforms that transformed Qin from a backward state into one that surpasses the other six states. It is generally regarded that this is the point where Qin started to become the most dominant state in China.

Ascension of the Kingdoms

In 334 B.C.E., the rulers of Wei and Qi agreed to recognize each other as Kings, formalizing the independence of the states and the powerlessness of the Zhou throne since the beginning of the Eastern Zhou dynasty. The king of Wei and the king of Qi joined the ranks of the king of Chu, whose predecessors had been kings since the Spring and Autumn period. From this point on, all the other states eventually declare their kingship, signifying the beginning of the end of the Zhou dynasty.

In 325 B.C.E., the ruler of Qin declared himself king.

In 323 B.C.E., the rulers of Han and Yan declared themselves king.

In 318 B.C.E., the ruler of Song, a relatively minor state, declared himself king.

The ruler of Zhao held out until around 299 B.C.E., and was the last to declare himself king.

Chu expansion and defeats

Early in the Warring States period, Chu was one of the strongest states in China. The state rose to a new level around 389 B.C.E. when the king of Chu named the famous reformer Wu Qi to be his prime minister.

Chu rose to its peak in 334 B.C.E. when it gained vast amounts of territory. The series of events leading up to this began when Yue prepared to attack Qi. The king of Qi sent an emissary who persuaded the king of Yue to attack Chu instead. Yue initiated a large scale attack at Chu, but was devastatingly defeated by Chu's counter-attack. Chu then proceeded to conquer the state of Yue. This campaign expanded the Chu's borders to the coast of China.

The Domination of Qin and the resulting Grand Strategies

Towards the end of the Warring States Period, the state of Qin became disproportionately powerful compared to the other six states. As a result, the policies of the six states became overwhelmingly oriented towards dealing with the Qin threat, with two opposing schools of thought: Hezong ("vertically linked"), or alliance with each other to repel Qin expansionism; and Lianheng ("horizontally linked"), or alliance with Qin to participate in its ascendancy. There were some initial successes in Hezong, though it eventually broke down. Qin repeatedly exploited the Lianheng strategy to defeat the states one by one. During this period, many philosophers and tacticians traveled around the states recommending the rulers to put their respective ideas into use. These "lobbyists" were famous for their tact and intellect, and were collectively known as Zonghengjia, taking its name from the two main schools of thought.

In 316 B.C.E., Qin conquered the Shu area.

Around 300 B.C.E., Qi was almost totally annihilated by a coalition of five states led by Yue Yi of the Yan (Qin was among those five). Although under General Tian Shan Qi managed to recover their lost territories, it would never be a great power again. The Yan was also too exhausted afterwards to be of much importance in international affairs after this campaign.

In 293 B.C.E. the Battle of Yique against Wei and Han resulted in victory for the Qin. This effectively removed the Wei and Han threat to further Qin aspirations.

In 278 B.C.E., the Qin attacked the Chu and managed to capture their capital city, Ying, forcing the Chu king to move eastwards to Shouchun. This campaign virtually destroyed the Chu's military might, although they recovered sufficiently to mount serious resistance against the Qin 50 years later.

In 260 B.C.E., the Battle of Changping was fought between the Qin and the Zhao, resulting in a catastrophic defeat for the latter. Although both sides were utterly exhausted after the titanic clash, the Zhao, unlike the Qin, could not recover after the event.

In about 50 years the Qin superiority was secure, thanks to its powerful military and, in part, constant feuding between the other states.

Qin's conquest of China

In 230 B.C.E., Qin conquers Han.

In 225 B.C.E., Qin conquers Wei.

In 223 B.C.E., Qin conquers Chu.

In 222 B.C.E., Qin conquers Yan and Zhao.

In 221 B.C.E., Qin conquers Qi, completing the unification of China, and ushering in the Qin dynasty.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Lawton, Thomas. Chinese Art of the Warring States Period: Change and Continuity, 480-222 B.C.E. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0934686501

- Loewe, Michael, and Edward L. Shaughnessy. The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 B.C.E. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 9780521470308

- Zhang, Qiyun, and Dongfang Li. China's Cultural Achievements During the Warring States Period. Yangmingshan, Taiwan: Chinese Culture University Press, China Academy, 1983.

- Zhongguo li shi bo wu guan, Yu Weichao, and Wang Guanying. A Journey into China's Antiquity. Beijing: Morning Glory Publishers, 1997. ISBN 978-7505404830

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.