Tibet

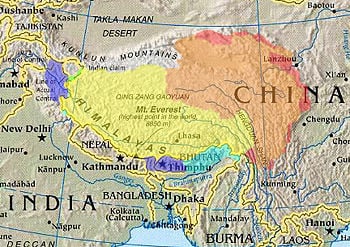

| Tibetan areas designated by the PRC.[1] | |||||||||

| Tibet Autonomous Region (actual control).[2] | |||||||||

| Claimed by India as part of Aksai Chin.[3] | |||||||||

| Claimed (not controlled) by the PRC as part of the TAR.[2] | |||||||||

| Other historically/culturally-Tibetan areas.[4] | |||||||||

Tibet, called “Bod” by Tibetans, or 西藏 (Xīzàng) by the Chinese, is a plateau region in Central Asia and the indigenous home to the Tibetan people. With an average elevation of 16,000 feet, (4,900 meters) it is the highest region on earth and is commonly referred to as the "Roof of the World." China, which presently controls Tibet, maintains it is a province-level entity, the Tibet Autonomous Region.

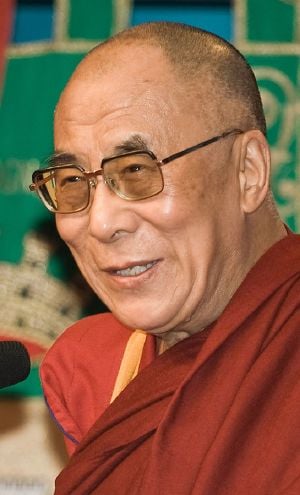

The Tibetan Empire came into existence in the seventh century when Emperor Songtsän Gampo united numerous tribes of the region. From 1578, leadership of Tibet has been in the hands of the Dalai Lamas, whose succession is based on the doctrine of reincarnation, and who are known as spiritual leaders, although their historical status as rulers is disputed.

Tibet was forcibly incorporated into the People's Republic of China in 1950. By virtue of its claim over all mainland Chinese territory, Tibet also has been claimed by Taiwan. The government of the People's Republic of China and the Government of Tibet in Exile disagree over when Tibet became a part of China, and whether this incorporation is legitimate according to international law.

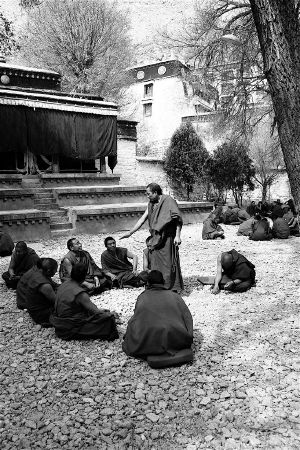

According to a number of international non-governmental organizations, Tibetans are denied most rights guaranteed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including the rights to self-determination, freedom of speech, assembly, expression, and travel; Tibetan monks and nuns who profess support for the Dalai Lama have been treated with extreme harshness by the PRC Chinese authorities.

Definitions

When the Government of Tibet in Exile and the Tibetan refugee community abroad refer to Tibet, they mean the areas consisting of the traditional provinces of Amdo, Kham, and Ü-Tsang, but excluding Sikkim, Bhutan, and Ladakh that have formed part of the Tibetan cultural sphere.

When the People's Republic of China refers to Tibet, it means the Tibet Autonomous Region: a province-level entity which includes Arunachal Pradesh, which used to be part of Tibet but is a state set up and occupied by India. The Tibet Autonomous Region covers the Dalai Lama's former domain, consisting of Ü-Tsang and western Kham, while Amdo and eastern Kham are part of Qinghai, Gansu, Yunnan, and Sichuan, traditionally part of China.

The difference in definition is a major source of dispute. The distribution of Amdo and eastern Kham into surrounding provinces was initiated by the Yongzheng Emperor of the Qing Dynasty of China, which exercised sovereignty over Tibet during the eighteenth century and has been continuously maintained by successive Chinese governments. Tibetan exiles, in turn, consider the maintenance of this arrangement from the eighteenth century as part of a divide-and-rule policy.

The modern Chinese name for Tibet, 西藏 (Xīzàng), is a phonetic transliteration derived from the region called Tsang (western Ü-Tsang). The name originated during the Qing Dynasty of China, ca. 1700.

The English word Tibet, is derived from the Arabic word Tubbat, which comes via Persian from the Turkic word Töbäd (plural of Töbän), meaning "the heights." The word for Tibet in Medieval Chinese, 吐蕃 (Pinyin Tǔfān, often given as Tubo), is derived from the same Turkic word.

Geography

Located on the Tibetan Plateau, the world's highest region, Tibet is bordered on the north and east by China, on the west by the Kashmir Region of India and on the south by Nepal, Bangladesh and Bhutan.

Tibet occupies about 471,700 square miles (1,221,600 square kilometers) on the high Plateau of Tibet surrounded by enormous mountains. Historic Tibet consists of several regions:

- Amdo in the northeast, incorporated by China into the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu and Sichuan.

- Kham in the east, divided between Sichuan, northern Yunnan and Qinghai.

- Western Kham, part of the Tibetan Autonomous Region

- Ü-Tsang (dBus gTsang) (Ü in the center, Tsang in the center-west, and Ngari (mNga' ris) in the far west), part of the Tibetan Autonomous Region

Tibetan cultural influences extend to the neighboring nations of Bhutan, Nepal, adjacent regions of India such as Sikkim and Ladakh, and adjacent provinces of China where Tibetan Buddhism is the predominant religion.

The Chang Tang plateau in the north extends more than 800 miles (1,300 km) across with an average elevation of 15,000 feet (4,500 meters) above sea level. It has brackish lakes and no rivers. The plateau descends in elevation towards the east. Mountain ranges in the southeast create a north-south barrier to travel and communication.

The Kunlun Mountains, with its highest peak Mu-tzu-t’a-ko reaching 25,338 feet (7,723 meters) form a border to the north. The Himalaya Mountains, one of the youngest mountain ranges in the world at only four million years old, form the western and southern border — the highest peak is Mount Everest, which rises to 29,035 feet (8,850 meters) on the Tibet–Nepal border. North of Ma-fa-mu Lake and stretching east is the Kang-ti-ssu Range, with several peaks exceeding 20,000 feet. The Brahmaputra River, which flows across southern Tibet to India, separates this range from the Himalayas.

The Indus River, known in Tibet as the Shih-ch'üan Ho, has its source in western Tibet near the sacred Mount Kailas, and flows west across Kashmir to Pakistan. The Hsiang-ch'üan River flows west to become the Sutlej River in western India, the K'ung-ch'üeh River eventually join the Ganges River, and the Ma-ch'üan River flows east and, after joining the Lhasa River, forms the Brahmaputra River. The Salween River flows from east-central Tibet, through Yunnan to Myanmar. The Mekong River has its source in southern Tsinghai as two rivers—the Ang and Cha—which join near the Tibet border to flow through eastern Tibet and western Yunnan to Laos and Thailand. The Yangtze River arises in southern Tsinghai.

Lakes T'ang-ku-la-yu-mu, Na-mu, and Ch'i-lin are the three largest lakes and are located in central Tibet. In western Tibet are two adjoining lakes, Ma-fa-mu Lake, sacred to Buddhists and Hindus, and Lake La-ang.

The climate is dry nine months of the year, and average snowfall is only 18 inches, due to the rain shadow effect whereby mountain ranges prevent moisture from the ocean from reaching the plateaus. Western passes receive small amounts of fresh snow each year but remain traversable all year round. Low temperatures prevail through the desolate western regions, where vegetation is limited to low bushes, and where wind sweeps unchecked across vast expanses of arid plain. The cool dry air means grain can be stored for 50 to 60 years, dried meat will last for a year, and epidemics are rare.

Northern Tibet is subject to high temperatures in the summer and intense cold in the winter. The seasonal temperature variation is minimal, with the greatest temperature differences occurring during a 24-hour period. Lhasa, at an elevation of 11,830 feet, has a maximum daily temperature of 85°F (30°C) and a minimum of -2°F (-19°C).

The arid climate of the windswept Chang Tang plateau supports little except grasses. Plant life in the river valleys and in the south and southeast includes willows, poplars, conifers, teak, rhododendrons, oaks, birches, elms, bamboo, sugarcane, babul trees, thorn trees, and tea bushes. The leaves of the lca-wa, khumag, and sre-ral, which grow in the low, wet regions, are used for food. Wildflowers include the blue poppy, lotus, wild pansy, oleander, and orchid.

The forests have tigers, leopards, bears, wild boars, wild goats, stone martens (a kind of cat), langurs, lynx, jackals, wild buffaloes, pha-ra (a small jackal), and gsa' (a small leopard). The high grasslands and dry bush areas have brown bears, wild and bighorn sheep, mountain antelope, musk deer, wild asses, wild yaks, snakes, scorpions, lizards, and wolves. Water life includes types of fish, frog, crab, otter, and turtle. Birds include the jungle fowl, mynah, hawk, the gull, crane, sheldrake, cinnamon teal, and owls. Natural hazards include earthquakes, landslides, and snow.

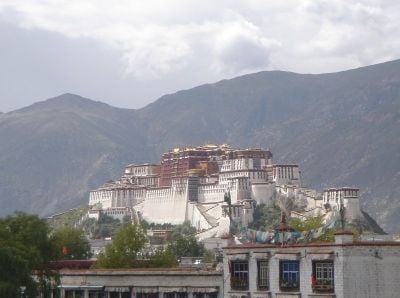

Lhasa is Tibet's traditional capital and the capital of the Tibet Autonomous Region. Lhasa contains the world heritage sites the Potala Palace and Norbulingka, the residences of the Dalai Lama, and a number of significant temples and monasteries including Jokhang and Ramoche Temple. Shigatse is the country's second largest city, west of Lhasa. Gyantse, Chamdo are also amongst the largest. Other cities include, Nagchu, Nyingchi, Nedong, Barkam, Sakya, Gartse, Pelbar, and Tingri; in Sichuan, Kangding (Dartsedo); in Qinghai, Jyekundo or Yushu, Machen, Lhatse, and Golmud.

History

Legendary beginning

According to Tibetan legend, the Tibetan people derived from the mating of a monkey and an ogress in Yarlung valley. The Fifth Dalai Lama embellished the story by adding that the monkey was an emanation of Avalokiteshvara, and the ogress was an emanation of goddess Tara. In Kham, the epic hero King Gesar is considered the founding ancestor of the Kham Tibetans. Linguists surmise that Chinese and the "proto-Tibeto-Burman" language may have split sometime before 4000 B.C.E., when the Chinese began growing millet in the Yellow River valley while the Tibeto-Burmans remained nomads. Tibetan split from Burman around 500 C.E.

Zhang Zhung culture

Prehistoric Iron Age hill forts and burial complexes have been found on the Chang Tang plateau but the remoteness of the location is hampering archaeological research. The initial identification of this culture is the Zhang Zhung culture which is described in ancient Tibetan texts and is known as the original culture of the Bön religion. According to Annals of Lake Manasarowar, at one point the Zhang Zhung civilization, which started sometime before 1500 B.C.E., comprised 18 kingdoms in the west and northwest portion of Tibet, centered around sacred Mount Kailash. At that time the region was warmer.

The Tibetan Empire

Tibet enters recorded history in the Geography of Ptolemy under the name batai (βαται), a Greek transcription of the indigenous name Bod. Tibet next appears in history in a Chinese text where it is referred to as fa. The first incident from recorded Tibetan history which is confirmed externally occurred when King Namri Lontsen sent an ambassador to China in the early seventh century.

Early Tibet was divided into princedoms, which in the sixth century were consolidated under a king, Gnam-ri srong-brtsan (570-619 C.E.), who commanded 100,000 warriors. His son Songtsän Gampo (604–650 C.E.), the 33rd King of Tibet, united parts of the Yarlung River Valley and is credited with expanding Tibet's power and with inviting Buddhism to Tibet. In 640 he married Princess Wencheng, the niece of the powerful Chinese Emperor Taizong, of Tang China. Songtsen Gampo, defeated the Zhang Zhung in 644 C.E.

Tibet divided

The reign of Langdarma (838-842) was plagued by external troubles. The Uyghur state to the North collapsed under pressure from the Kirghiz in 840, and many displaced persons fled to Tibet. Langdarma was assassinated in 842. The Tibetan empire collapsed, either as the result of a war of succession, or war between rival generals. Allies of one posthumous heir controlled Lhasa, while allies of the other went to Yalung. Nyima-Gon, a representative of the ancient Tibetan royal house, founded the first Ladakh dynasty, in the Kashmir region, to the east of present day Ladakh. Central rule was largely nonexistent over the Tibetan region from 842 to 1247, and Buddhism declined in central Tibet, surviving surreptitiously in the region of Kham.

A son of the king of the western Tibet Kingdom of Guge became a Buddhist monk and was responsible for inviting the renowned Indian pandit Atisha to Tibet in 1042, thus ushering in the Chidar (Phyi dar) phase of Buddhism there. Tibetan scholar Dkon-mchog rgyal-po established the Sakya Monastery in Lhokha in 1073. Over the next two centuries the Sakya monastery grew to a position of prominence in Tibetan life and culture. At this time, some monasteries began practicing a tradition whereby a deceased lama (head of the monastery) was succeeded by a boy judged to be his reincarnation.

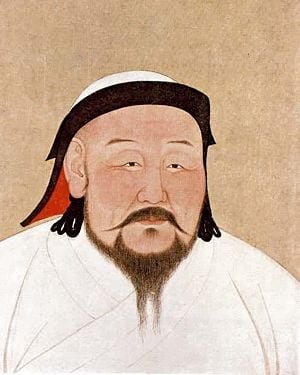

Mongol sovereignty

The Mongol khans had ruled northern China by conquest since 1215, as emperors of the Yuan Dynasty. In 1240, the Mongols, investigating an option to attack China from the west, marched into central Tibet and attacked several monasteries. Köden, the younger brother of Mongol ruler Güyük Khan, invited the leader of the Sakya sect, to come to his capital and formally surrender Tibet to the Mongols. The Sakya lama arrived in Kokonor with his two nephews, Drogön Chögyal Phagpa (1235-1280) and Chana Dorje (1239-1267) (Phyag-na Rdo-rje) (1239-1267) in 1246. Köden recognized the Sakya lama as temporal ruler of Tibet in 1247, an event claimed by modern Chinese historians as marking the incorporation of Tibet into China. Pro-Tibetan historians argue that China and Tibet remained two separate units within the Mongol Empire.

Kublai Khan, who was elected khan in 1260 following the death of his brother Möngke, named Drogön Chögyal Phagpa “state preceptor,” his chief religious official in Tibet. In 1265, Drogön Chögyal Phagpa returned to Tibet and tried to impose Sakya hegemony with the appointment of Shakya Bzang-po (a long time servant and ally of the Sakyas) as the Dpon-chen ('great administrator') over Tibet in 1267. A census was conducted in 1268 and Tibet was divided into 13 myriarchies. In 1270, Phagpa was named Dishi ('imperial preceptor'), and his position as ruler of Tibet was reconfirmed.

Sakya rule continued into the middle of the fourteenth century, although it was challenged by a revolt of the Drikung Kagyu sect with the assistance of Hulagu Khan of the Ilkhanate in 1285. The revolt was suppressed in 1290 when the Sakyas and eastern Mongols burned Drikung Monastery and killed 10,000 people.

Phag-mo-gru-pa dynasty

The collapse of the Mongol Yuan dynasty in 1368 led to the overthrow of the Sakya in Tibet. When the native Chinese Ming dynasty evicted the Mongols, Tibet regained its independence, and for more than 100 years the Phag-mo-gru-pa line governed in its own right. Buddhism revived, literary activity was intense, and monasteries were built and decorated by Chinese craftsmen. In 1435, the lay princes of Rin-spungs, ministers of Gong-ma, and patrons of the Karma-pa sect, rebelled and by 1481 had seized control of the Phag-mo-gru court.

Yellow Hat sect

The Buddhist reformer Tsong-kha-pa, who had studied with the leading teachers of the day, formulated his own doctrine emphasizing the moral and philosophical teachings of Atisha over the magic and mysticism of Sakya. In 1409, he founded a monastery at Dga'-ldan, noted for strict monastic discipline, which appealed to people weary of rivalry and strife between wealthy monasteries. After his death, devoted and ambitious followers built around his teaching and prestige what became the Dge-lugs-pa, or Yellow Hat sect.

The Dalai Lama lineage

The Mongol ruler Altan Khan bestowed the title of “Dalai Lama” upon Sonam Gyatso, the third head of the Gelugpa Buddhist sect, in 1578, thus reviving the patron-priest relationship that had existed between Kublai Khan and 'Phags-pa. "Dalai" means "ocean" in Mongolian, and "lama" is the Tibetan equivalent of the Sanskrit word "guru," and is commonly translated to mean "spiritual teacher." Gyatso was an abbot at the Drepung monastery, and was widely considered the most eminent lama of his time. Although Sonam Gyatso became the first lama to hold the title "Dalai Lama," due to the fact that he was the third member of his lineage, he became known as the "third Dalai Lama." The previous two titles were conferred posthumously upon his predecessors. The Dalai Lama is believed to be the embodiment of a spiritual emanation of the bodhisattva—Avalokitesvara, the mythic progenitor of Tibetans. Succession passes to a child, born soon after the death of a Dalai Lama, who is believed to have received the spirit of the deceased.

Fifth Dalai Lama

The fourth Dalai Lama supposedly reincarnated in Mongol Altan Khan's family. Mongol forces entered Tibet to push this claim, opposed by the Karma-pa sect and Tibet's secular aristocracy. The fourth Dalai Lama died in 1616. New Oyrat Mongol leader Güüshi Khan invaded Tibet in 1640. In 1642, Güüshi enthroned the Fifth Dalai Lama as ruler of Tibet.

Lobsang Gyatso, the fifth Dalai Lama, (1617-1682) was the first Dalai Lama to wield effective political power over central Tibet. He is known for unifying Tibet under the control of the Geluk school of Tibetan Buddhism, after defeating the rival Kagyu and Jonang sects, and the secular ruler, the prince of Shang, in a prolonged civil war. His efforts were successful in part because of aid from Gushi Khan. The Jonang monasteries were either closed or forcibly converted, and that school remained in hiding until the latter part of the twentieth century. The fifth Dalai Lama initiated the construction of the Potala Palace in Lhasa, and moved the center of government there from Drepung.

Manchu sovereignty

The Ch'ing, or Manchu dynasty, was installed in China in 1644. The Manchu wanted good relations with Tibet because of the Dalai Lama's prestige among the Mongols. Meanwhile, Tibet clashed with Bhutan in 1646 and 1657, and with Ladakh up to 1684.

The Manchus did not find out about the death of the Fifth Dalai Lama (in 1682), and the appearance of his supposed reincarnation, until 1696. Infuriated, Manchu Emperor K’ang-hsi (who reigned 1661–1722) found an ally in Mongol Lha-bzang Khan, the fourth successor of Güüshi, who sought to assert rights as king in Tibet. The behavior of the sixth Dalai Lama (1683-1706), a poetry-writing womanizer, provided an excuse for Lha-bzang Khan, in 1705, to kill minister regent Sangs-rgyas rgya-mtsho and depose the Dalai Lama.

Fearing Mongol control of Tibet, in 1720 Manchu troops drove out the Mongols, thus gaining a titular sovereignty over Tibet, leaving representatives and a small garrison in Lhasa, and government in the hands of the Dalai Lamas. Manchu troops quelled a civil war in Tibet in 1728, restored order after the assassination of a political leader in 1750, and drove out Gurkhas, who had invaded from Nepal in 1792. Chinese contact helped shape the Tibetan bureaucracy, army, and mail service. Chinese customs influenced dress, food, and manners.

British interest

Portuguese missionaries visited in 1624 and built a church, and two Jesuit missionaries reached Lhasa in 1661. The eighteenth century brought more Jesuits and Capuchins, who gradually met opposition from Tibetan lamas who finally expelled them in 1745. In 1774, a Scottish nobleman George Bogle investigating trade for the British East India Company, introduced the first potato crop. All foreigners except Chinese were excluded from Tibet after 1792.

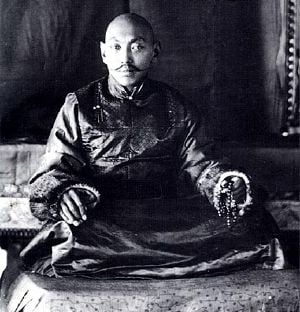

British colonial officials in India attempted to secure a foothold in Tibet, who saw the region as a trade route to China, then as a way to counter Russian advances towards India. In 1865 Great Britain began secretly mapping Tibet. Trained Indian surveyor-spies disguised as pilgrims or traders counted their strides on their travels across Tibet and took readings at night. In 1904, a British diplomatic mission, led by Colonel Francis Younghusband and accompanied by a large military escort, forced its way through to Lhasa, killing 1,300 Tibetans in Gyangzê. The 13th Dalai Lama fled to China. A treaty was concluded between Britain and Tibet, and the Anglo-Chinese Convention in 1906, that recognized Chinese sovereignty.

Chinese sovereignty resisted

The Anglo-Chinese convention encouraged China to invade Tibet in 1910. The 13th Dalai Lama fled again, this time to India. But after the Chinese Revolution in 1911–1912, the Tibetans expelled the Chinese and declared their independence. A convention at Simla in 1914 provided for an autonomous Tibet, and for Chinese sovereignty in the region called Inner Tibet. The Chinese government repudiated the agreement, and in 1918, strained relations between Tibet and China exploded into armed conflict. Efforts to conciliate the dispute have failed, and fighting flared up in 1931. The Dalai Lamas continued to govern Tibet as an independent state.

The subsequent outbreak of World War I and the Chinese Civil War caused Western powers and infighting factions of China proper to lose interest in Tibet, and the 13th Dalai Lama ruled undisturbed until his death in 1933.

In 1935, Tenzin Gyatso was born in Amdo in eastern Tibet and was recognized as the latest reincarnation — the 14th Dalai Lama. In the 1940s during World War II, Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer became tutor and consort to the young Dalai Lama giving him a sound knowledge of Western culture and modern society, until he was forced to leave with the Chinese invasion in 1950.

Chinese invade

In October 1950, Communist Chinese troops invaded Tibet. The 14th Dalai Lama, only 15 years old, was invested as leader, but poorly equipped Tibetan troops were soon crushed. An appeal by the Dalai Lama to the United Nations was denied, while Great Britain and India offered no help. In May 1951, a Tibetan delegation signed a dictated treaty that gave the Dalai Lama authority in domestic affairs, China control of Tibetan foreign and military affairs, and provided for the return from China of the Tibetan Buddhist spiritual leader, the Panchen Lama, allegedly a communist partisan. The Communist Chinese military entered Lhasa in October, and the Panchen Lama arrived there in April 1952.

Chinese rule

During 1952 the Chinese built airfields and military roads. A purge of anti-communists was reportedly carried out early in 1953. India recognized Tibet as part of China in 1954 and withdrew its troops from two Tibetan frontier trading posts. The Dalai Lama was elected a vice-president of the National People's Congress, the Chinese legislative body. A committee was set up in 1956 to prepare a constitution, the Dalai Lama was named chairman, and the Panchen Lama first vice-chairman.

An uprising broke out in Amdo and eastern Kham in June 1956. The resistance, supported by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), eventually spread to Lhasa, but was crushed by 1959. Tens of thousands of Tibetans were killed. The 14th Dalai Lama and other government principals then fled to exile in India, but isolated resistance continued in Tibet until 1969 when the CIA abruptly withdrew its support.

Although the Panchen Lama remained a virtual prisoner, the Chinese set him as a figurehead in Lhasa, claiming that he headed the legitimate Government of Tibet since the Dalai Lama had fled to India. In 1965, the area that had been under the Dalai Lama's control from 1910 to 1959 (U-Tsang and western Kham) was set up as an autonomous region. The monastic estates were broken up and secular education introduced. During the Cultural Revolution, Chinese Red Guards inflicted a campaign of organized vandalism against cultural sites in the entire PRC, including Tibet. Some young Tibetans joined in the campaign of destruction, voluntarily due to the ideological fervor that was sweeping the entire PRC and involuntarily due to the fear of being denounced as enemies of the people. Over 6,500 monasteries were destroyed, and only a handful of the most important monasteries remained without damage. Hundreds of thousands of Buddhist monks and nuns were forced to return to secular life.

In 1989, the Panchen Lama was allowed to return to Shigatse, where he addressed a crowd of 30,000 and described what he saw as the suffering of Tibet and the harm being done to his country in terms reminiscent of a petition he had presented to Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in 1962. Five days later, he mysteriously died of a massive heart attack at the age of 50.

In 1995 the Dalai Lama named six-year-old Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as the 11th Panchen Lama without Chinese approval, while the secular PRC named another child, Gyancain Norbu. Gyancain Norbu was raised in Beijing and has appeared occasionally on state media. Tibetans reject the PRC-selected Panchen Lama. Gedhun Choekyi Nyima and his family have gone missing - widely believed to be imprisoned by China.

All governments recognize the PRC's sovereignty over Tibet today, and none have recognized the Government of Tibet in Exile in India.

Government and politics

Before the Chinese occupied Tibet in 1951, the country had a theocratic government with the Dalai Lama the spiritual and temporal head. From 1951, the Chinese relied on military control, working towards regional autonomy, which was granted in 1965. Since then, Tibet has been one of the People’s Republic of China’s five autonomous regions.

An autonomous region has its own local government, but with more legislative rights. It is a minority entity and has a higher population of a particular minority ethnic group. Following Soviet practice, the chief executive is typically a member of the local ethnic group while the party general secretary is non-local and usually Han Chinese.

The Tibet Autonomous Region is divided into the municipality of Lhasa, directly under the jurisdiction of the regional government, and prefectures (Qamdo, Shannan, Xigazê, Nagqu, Ngari, and Nyingchi), which are subdivided into counties.

The army comprises regular Chinese troops under a Chinese commander, stationed at Lhasa. There are military cantonments in major towns along the borders with India, Nepal, and Bhutan. Tibetans have been forcibly recruited into regular, security, and militia regiments.

The Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), officially the Central Tibetan Administration of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, is a government in exile headed by Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, which claims to be the rightful and legitimate government of Tibet. It is commonly referred to as the Tibetan Government in Exile.

The CTA is headquartered in Dharamsala, India, where the Dalai Lama settled after fleeing Tibet in 1959 after a failed uprising against Chinese rule. It claims jurisdiction over the entirety of the Tibet Autonomous Region and Qinghai province, as well as parts of the neighboring provinces of Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan - all of which is termed "Historic Tibet" by CTA.

The CTA exercises many governmental functions in relation to the Tibetan exile community in India, which numbers around 100,000. The administration runs schools, health services, cultural activities and economic development projects for the Tibetan community. It also provides welfare services for the hundreds of Tibetans who continue to arrive in India each month as refugees after having crossed from China, usually via Nepal, on foot. The government of India allows the CTA to exercise effective jurisdiction in these matters over the Tibetan communities in northern India.

The CTA is not recognized as a government by any country, but it receives financial aid from governments and international organizations for its welfare work among the Tibetan exile community in India. This does not imply recognition of the CTA as a government.

Exile view of the status of Tibet

The government of Tibet in exile says that the issue is that of the right to self-determination of the Tibetan people. It says that:

- Approximately 1.2 million have died as a result of the Chinese occupation since 1950, and up to 10 percent of the Tibetan population was interned, with few survivors.

- Despite the central government's claim to have granted most religious freedoms, Tibetan monasteries are under stringent government control, and in 1998, three monks and five nuns died while in custody, after suffering beatings and torture for having shouted slogans supporting the Dalai Lama and Tibetan independence.

- Projects that the PRC touts to have benefited Tibet, such as the China Western Development economic plan or the Qinghai-Tibet Railway, are alleged to be politically-motivated actions to consolidate central control over Tibet by facilitating militarization and Han migration.

People's Republic of China view

The government of the PRC maintains that the Tibetan Government did almost nothing to improve the Tibetans' material and political standard of life during its rule from 1913-1959, and that they opposed any reforms proposed by the Chinese government. The government of the PRC claims that the lives of Tibetans have improved immensely compared to self-rule before 1950:

- Gross domestic product of the TAR in 2007 was 30 times that of before 1950

- Workers in Tibet have the second highest wages in China

- The TAR has 22,500 km of highways, as opposed to none in 1950

- All secular education in the TAR was created after the revolution, the TAR now has 25 scientific research institutes as opposed to none in 1950

- Infant mortality has dropped from 43 percent in 1950 to 0.661 percent in 2000

- Life expectancy has risen from 35.5 years in 1950 to 67 in 2000

- 300 million renminbi have been allocated since the 1980s for the maintenance and protection of Tibetan monasteries

- The Cultural Revolution and the cultural damage it wrought upon the entire PRC has been condemned as a nationwide catastrophe. Its main instigators, the Gang of Four, have been brought to justice, and a re-occurrence is unthinkable in an increasingly modernized China.

- The China Western Development plan is viewed by the PRC as a massive, benevolent, and patriotic undertaking by the wealthier eastern coast to help the western parts of China, including Tibet, catch up in prosperity and living standards.

Economy

Tibet is rich in mineral resources, but its economy has remained underdeveloped. Surveys of western Tibet in the 1930s and 1940s discovered goldfields, deposits of borax, as well as radium, iron, titanium, lead, and arsenic. There is a 25-mile belt of iron ore along the Mekong River, plentiful coal, and oil-bearing formations. Other mineral resources include oil shale, manganese, lead, zinc, quartz, and graphite. Precious and semi-precious stones include jade and lapis lazuli, among others. The forest timber resource in the Khams area alone was estimated at 3.5-billion cubic feet. The swift-flowing rivers provide enormous hydroelectric power potential, possibly contributing one-third of China's potential resources. Because of the inaccessibility of Tibet's forests, forestry is just in its developing stages.

The economy of Tibet is dominated by subsistence agriculture. Livestock raising is the primary occupation mainly on the Tibetan Plateau, including sheep, cattle, goats, camels, yaks (large, long-haired oxen) and horses. However the main crops grown are barley, wheat, buckwheat, rye, potatoes and assorted fruits and vegetables. Butter from the yak and the mdzo-mo (a crossbreed of the yak and the cow) is the main dairy product.

Under Chinese control, the small hydroelectric power station at Lhasa was repaired, a new thermal station was installed in Jih-k'a-tse. Hydrographic stations were established to determine hydroelectric potential. An experimental geothermal power station was commissioned in the early 1980s, with the transmitting line terminating in Lhasa. Emphasis was placed on agricultural-processing industries and tourism. The PRC government exempts Tibet from all taxation and provides 90 percent of Tibet's government expenditures. Tibet's economy depends on Beijing.

Qinghai-Tibet railway

The Qinghai-Tibet Railway which links the region to Qinghai in China proper was opened in 2006. The Chinese government claims that the line will promote the development of impoverished Tibet. But opponents argue the railway will harm Tibet since it would bring in more Han Chinese residents, the country's dominant ethnic group, who have been migrating steadily to Tibet over the last decade, bringing with them their popular culture. Opponents say the large influx of Han Chinese will ultimately extinguish the local culture. Others argue that the railway will damage Tibet's fragile ecology.

Tourism

Tibet's tourism industry has grown, especially following the completion of Qingzang Railway in July 2006. Tibet received 2.5 million tourists in 2006, including 150,000 foreigners. Increased interest in Tibetan Buddhism has helped make tourism an increasingly important sector, and this is actively promoted by the authorities. Tourists buy handicrafts including hats, jewelry (silver and gold), wooden items, clothing, quilts, fabrics, Tibetan rugs and carpets.

Limited data

As an autonomous region of China, data on imports and exports is not readily available, and any data that is derived from state publications is issued for publicity purposes. According to PRC figures, Tibet's GDP in 2001 was 13.9 billion yuan (US$1.8-billion). Tibet's economy has had an average growth of 12 percent per year from 2000 to 2006, a figure that corresponded to the five-year goal issued at the start of the period.

The per capita GDP reached 10,000 renminbi (mainland China unit of currency) in 2006 for the first time. That would convert to $1,233, which would place Tibet between Mali (164th) and Nigeria (165th) on the International Monetary Fund list. By comparison, the PRC per capita GDP is $7,598, or 87th.

Demographics

Historically, the population of Tibet consisted of primarily ethnic Tibetans and some other ethnic groups.

According to tradition the original ancestors of the Tibetan people, as represented by the six red bands in the Tibetan flag, are: the Se, Mu, Dong, Tong, Dru and Ra. Other traditional ethnic groups with significant population or with the majority of the ethnic group residing in Tibet (excluding a disputed area with India) include Bai people, Blang, Bonan, Dongxiang, Han, Hui people, Lhoba, Lisu people, Miao, Mongols, Monguor (Tu people), Menba (Monpa), Mosuo, Nakhi, Qiang, Nu people, Pumi, Salar, and Yi people.

The proportion of the non-Tibetan population in Tibet is disputed. The issue of the proportion of the Han Chinese population in Tibet is a politically sensitive one. The Central Tibetan Administration says that the People's Republic of China has actively swamped Tibet with Han Chinese migrants in order to alter Tibet's demographic makeup. The Government of Tibet in Exile questions all statistics given by the PRC government, since they do not include members of the People's Liberation Army garrisoned in Tibet, or the large floating population of unregistered migrants. The Qinghai-Tibet Railway (Xining to Lhasa) is also a major concern, as it is believed to further facilitate the influx of migrants.

The PRC government does not view itself as an occupying power and has vehemently denied allegations of demographic swamping. The PRC also does not recognize Greater Tibet as claimed by the Government of Tibet in Exile, saying that those areas outside the TAR were not controlled by the Tibetan government before 1959 in the first place, having been administered instead by other surrounding provinces for centuries.

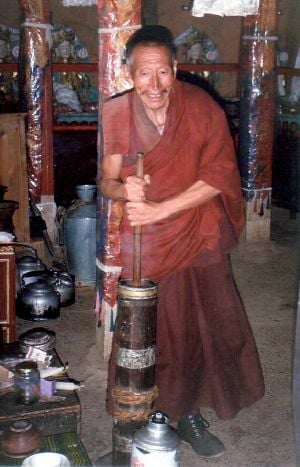

Religion

Religion is extremely important to Tibetans. Tibetan Buddhism is a subset of Tantric Buddhism, also known as Vajrayana Buddhism, which is also related to the Shingon Buddhist tradition in Japan. Tibetan Buddhism is also practiced in Mongolia, the Buryat Republic, the Tuva Republic, and in the Republic of Kalmykia. Tibet is also home to the original spiritual tradition called Bön, the indigenous shamanistic religion of the Himalayas. Notable monasteries: Ani Tsankhung Nunnery, Changzhu Temple, Dorje Drak, Drepung, Drigung, Dzogchen, Ganden Monastery, Jokhang, Kumbum (Kham), Labrang, Menri, Namgyal, Narthang, Palcho, Ralung , Ramoche Temple, Sakya, Sanga , Sera, Shalu, Shechen, Surmang, Tashilhunpo, Tsurphu, and Yerpa.

In Tibetan cities, there are also small communities of Muslims, known as Kachee, who trace their origin to immigrants from three main regions: Kashmir (Kachee Yul in ancient Tibetan), Ladakh, and the Central Asian Turkic countries. Islamic influence in Tibet also came from Persia. After 1959 a group of Tibetan Muslims made a case for Indian nationality based on their historic roots to Kashmir and the Indian government declared all Tibetan Muslims Indian citizens later that year. There is also a well established Chinese Muslim community (Gya Kachee), which traces its ancestry back to the Hui ethnic group of China. It is said that Muslim migrants from Kashmir and Ladakh first entered Tibet around the twelfth century. Marriages and social interaction gradually led to an increase in the population until a sizable community grew up around Lhasa.

The Potala Palace, former residence of the Dalai Lamas, is a World Heritage Site, as is Norbulingka, former summer residence of the Dalai Lama.

Nuns have taken a leading role in resisting Chinese authorities. Since the late 1980s, the Chinese crackdown on the resistance has become increasingly centered on nunneries, which have had strict rules imposed on them and informers planted. Nuns convicted of political offenses are not allowed to return to their worship.

Language

The Tibetan language is generally classified as a Tibeto-Burman language of the Sino-Tibetan language family. Spoken Tibetan includes numerous regional dialects which, in many cases, are not mutually intelligible. Moreover, the boundaries between Tibetan and certain other Himalayan languages are sometimes unclear. In general, the dialects of central Tibet (including Lhasa), Kham, Amdo, and some smaller nearby areas are considered Tibetan dialects, while other forms, particularly Dzongkha, Sikkimese, Sherpa, and Ladakhi, are considered for political reasons by their speakers to be separate languages. Ultimately, taking into consideration this wider understanding of Tibetan dialects and forms, "greater Tibetan" is spoken by approximately six million people across the Tibetan Plateau. Tibetan is also spoken by approximately 150,000 exile speakers who have fled from modern-day Tibet to India and other countries.

Family and class

Traditional marriage in Tibet, which involved both monogamy and polyandry, was related to the system of social stratification and land tenure, according to Melvyn C. Goldstein, who studied the issue on a field trip to the region in 1965-1967. Tibetan laymen traditionally were divided into two classes – the gerba (lords) and mi-sey (serfs). Membership of these classes was hereditary, and the linkage was passed on through parallel descent – daughters were linked to the lord of the mother, and sons to the lord of the father. There were two categories of serfs – tre-ba (taxpayer) and du-jung (small householder). Tre-ba were superior in terms of status and wealth, and were organized into family units which held sizable plots of land (up to 300 acres) from their lord. They held a written title to the land, and could not be evicted so long as they fulfilled their obligations, which were quite onerous, and involved providing human and animal labor, caring for animals on behalf of the lord, and paying tax. Du-jung existed in two varieties — the bound du-jung held smaller (one or two acre), non-inheritable plots, whereas the non-bound du-jung leased his services.

The system of marriage in tre-ba families meant that for purposes of keeping the corporate family intact through the generations, only one marriage could occur in each generation, to produce children with full rights of inheritance. Two conjugal families in a generation, with two sets of heirs, were thought likely to lead to partition of the corporate inheritance. To solve this problem, for example, in a family with two sons and one daughter, the daughter would move to the home of her husband, and the two sons would marry one woman, establishing a polyandrous marriage, thus keeping the inherited land and obligations intact. Since Tibetans believed that marriages involving three or four brothers to one wife were too difficult, surplus brothers would become celibate monks, and surplus daughters could become nuns.

Perpetuation of the corporate family across the generations was the prime concern for tre-ba families. The traditional Tibetan solution for a situation when a mother died before her son married, was to have the son and father share a new wife. If a family had two daughters and no sons, the daughters could enter into a polygynous marriage, sharing a husband.

Since du-jung gained access to land as individuals rather than corporate families, there was no need to pass on a corporate inheritance. Couples married for love, married monogamously, and established their own households, without pressure to maintain an extended family. Sometimes aged parents lived with one of their children. The only instances of polyandry found among du-jung occurred when family wealth was involved.

Education

Before 1950, there were a few secular schools in Tibet. Monasteries provided education, and some larger ones operated along the lines of theological universities. In the 1950s, government-run primary schools, community primary schools, and secondary technical and tertiary schools, including Tibet University, were established. A ten-year doctoral degree program in Buddhism is available at the state-run Tibet Buddhist College.

Culture

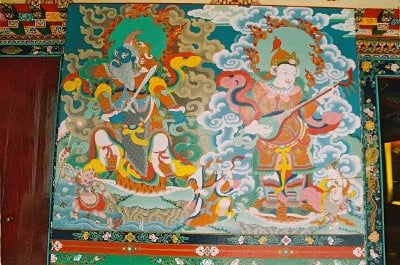

Tibet has a rich culture that shows a pervasive influence of Mahayana Buddhism, Tantric Buddhism, also known as Vajrayana Buddhism, as well as the indigenous shamanistic religion of the Himalayas is known as Bön. Greek statuary inspired both bronze and stone statues of the Buddha to be created for temple use.

Art

Tibetan art is deeply religious in nature, a form of sacred art. From the exquisitely detailed statues found in Gompas to wooden carvings to the intricate designs of the Thangka paintings, the overriding influence of Tibetan Buddhism on culture and art can be found in almost every object and every aspect of daily life.

The Greek skill in statuary, brought to neighboring India in the fourth century B.C.E. by Alexander the Great, led to a Greco-Buddhist synthesis. Whereas the Buddha did not previously have a standardized statuary representation, the Greek models inspired both bronze and stone statues of the Buddha to be created for temple use.

Thangka paintings, a syncretism of Chinese scroll-painting with Nepalese and Kashmiri painting, appeared in Tibet around the tenth century. Rectangular and painted on cotton or linen, they are usually traditional motifs depicting religious, astrological, and theological subjects, and sometimes the mandala. To ensure that the image will not fade, organic and mineral pigments are added, and the painting is framed in colorful silk brocades.

Tibetan rugs are primarily made from virgin wool of Tibetan highland sheep. The Tibetan uses rugs for almost any domestic use, from flooring, wall hangings, to horse saddles. Tibetan rugs were traditionally hand-made, but a few aspects of the rug making processes have been taken over by machine primarily because of cost, and the disappearance of expertise. Tibetan refugees took their knowledge of rug making to India and especially Nepal, where the rug business is one of the largest industries in the country.

Architecture

Tibetan architecture contains Oriental and Indian influences, and reflects a deeply Buddhist approach. The Buddhist wheel, along with two dragons, can be seen on nearly every gompa (Buddhist temple) in Tibet. The design of the Tibetan chörten (burial monument) can vary, from roundish walls in Kham to squarish, four-sided walls in Ladakh.

The most unusual feature of Tibetan architecture is that many of the houses and monasteries are built on elevated, sunny sites facing the south, and are often constructed using a mixture of rocks, wood, cement and earth. Little fuel is available for heat or lighting, so flat roofs are built to conserve heat, and multiple windows are constructed to let in sunlight. Walls are usually sloped inwards at 10 degrees as a precaution against frequent earthquakes in the mountainous area.

Standing at 117 meters in height and 360 meters in width, the Potala Palace is considered to be the most important example of Tibetan architecture. Formerly the residence of the Dalai Lama, it contains over a thousand rooms within 13 stories, and houses portraits of the past Dalai Lamas and statues of the Buddha. It is divided between the outer White Palace, which serves as the administrative quarters, and the inner Red Quarters, which houses the assembly hall of the lamas, chapels, 10,000 shrines, and a vast library of Buddhist scriptures.

Clothing

Tibetans are conservative in their dress, and though some have taken to wearing Western clothes, traditional styles abound. Women wear dark-colored wrap dresses over a blouse, and a colorful striped, woven wool apron signals that she is married. Men and women both wear long sleeves even in the hot summer months.

A khata is a traditional ceremonious scarf given in Tibet. It symbolizes goodwill, auspiciousness and compassion. It is usually made of silk and white symbolizing the pure heart of the giver. The khata is a highly versatile gift. It can be presented at any festive occasions to a host or at weddings, funerals, births, graduations, arrivals and departure of guests etc. The Tibetans commonly give a kind acknowledgment of tashi delek (good luck) at the time of presenting.

Cuisine

The most important crop in Tibet is barley, and dough made from barley flour called tsampa, is the staple food of Tibet. This is either rolled into noodles or made into steamed dumplings called momos. Meat dishes are likely to be yak, goat, or mutton, often dried, or cooked into a spicy stew with potatoes. Mustard seed is cultivated in Tibet, and therefore features heavily in its cuisine. Yak yoghurt, butter and cheese are frequently eaten, and well-prepared yoghurt is considered a prestige item. Butter tea is very popular to drink and many Tibetans drink up to 100 cups a day.

Other Tibetan foods include:

- Balep korkun - a central Tibetan flatbread that is made on a skillet.

- Thenthuk - a type of cold-weather soup made with noodles and various vegetables.

Jasmine tea and yak butter tea are drunk. Alcoholic beverages include:

In larger Tibetan towns and cities many restaurants now serve Sichuan-style Chinese food. Western imports and fusion dishes, such as fried yak and chips, are also popular. Nevertheless, many small restaurants serving traditional Tibetan dishes persist in both cities and the countryside.

Drama

The Tibetan folk opera, known as ache lhamo (sister goddess), is a combination of dances, chants and songs. The repertoire is drawn from Buddhist stories and Tibetan history. The Tibetan opera was founded in the fourteenth century by Thangthong Gyalpo, a lama and a bridge builder. Gyalpo and seven recruited girls organized the first performance to raise funds for building bridges. The tradition continued, and lhamo is held on various festive occasions such as the Linka and Shoton festival. The performance is usually a drama, held on a barren stage, that combines dances, chants and songs. Colorful masks are sometimes worn to identify a character, with red symbolizing a king and yellow indicating deities and lamas. The performance starts with a stage purification and blessings. A narrator then sings a summary of the story, and the performance begins. Another ritual blessing is conducted at the end of the play.

Music

The music of Tibet reflects the cultural heritage of the trans-Himalayan region, centered in Tibet. Tibetan music is religious music, reflecting the profound influence of Tibetan Buddhism on the culture. The music often involves chanting in Tibetan or Sanskrit. These chants are complex, often recitations of sacred texts or in celebration of various festivals. Yang chanting, performed without metrical timing, is accompanied by resonant drums and low, sustained syllables. Other styles include those unique to the various schools of Tibetan Buddhism, such as the classical music of the popular Gelugpa school, and the romantic music of the Nyingmapa, Sakyapa and Kagyupa schools.

Secular Tibetan music has been promoted by organizations like the Dalai Lama's Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts. This organization specialized in the lhamo, an operatic style, before branching out into other styles, including dance music like toeshey and nangma. Nangma is especially popular in the karaoke bars of Lhasa. Another form of popular music is the classical gar style, which is performed at rituals and ceremonies. Lu are a type of song that features glottal vibrations and high pitches. There are also epic bards who sing of Tibet's national hero Gesar.

Tibetan music has had a profound effect on some styles of Western music, especially New Age. Composers like Philip Glass and Henry Eichheim are most well-known for their use of Tibetan elements in their music. The first such fusion was Tibetan Bells, a 1971 release by Nancy Hennings and Henry Wolff. The soundtrack to Kundun, by Philip Glass, has helped to popularize Tibetan music.

Foreign styles of popular music, including Indian ghazal and filmi are popular, as is rock and roll, an American style which has produced Tibetan performers like Rangzen Shonu. Since the relaxation of some laws in the 1980s, Tibetan pop, popularized by Yadong, Jampa Tsering, the three-member group AJIA, four-member group Gao Yuan Hong, five-member group Gao Yuan Feng, and Dechen Shak-Dagsay are well-known, as are the sometimes politicized lyrics of nangma. Gaoyuan Hong in particular has introduced elements of Tibetan language rap into their singles.

Cinema

In recent years there have been a number of films produced about Tibet, most notably Hollywood films such as Seven Years in Tibet (1997), starring Brad Pitt, and Kundun, a biography of the Dalai Lama, directed by Martin Scorsese. Both of these films were banned by the Chinese government because of Tibetan nationalist overtones. Other films include Samsara (2001), The Cup and the 1999 Himalaya, a French-American produced film with a Tibetan cast set in Nepal and Tibet. In 2005, exile Tibetan filmmaker Tenzing Sonam and his partner Ritu Sarin made Dreaming Lhasa, the first internationally recognized feature film to come out of the diaspora to explore the contemporary reality of Tibet. In 2006, Sherwood Hu made Prince of the Himalayas, an adaptation of Shakespeare's Hamlet, set in ancient Tibet and featuring an all-Tibetan cast. Kekexili, or Mountain Patrol, is a film made by the National Geographic Society about a Chinese reporter who goes to Tibet to report on the issue involving the endangerment of Tibetan antelope.

Festivals

Tibet has various festivals which commonly are performed to worship Buddha throughout the year. Losar is the Tibetan New Year Festival, and involves a week of drama and carnivals, horse races and archery. The Monlam Prayer Festival follows it in the first month of the Tibetan calendar which involves dancing, sports events and picnics. On the 15th day of the fourth month, Saka dawa celebrates the birth and enlightenment of Sakyamuni and his entry to Nirvana. An outdoor opera is held and captured animals released. Worshipers flock to the Jokhang in Lhasa to pray. The Golden Star Festival held in the seventh to eighth month is to wash away passion, greed, and jealousy and to abandon ego. Ritual bathing in rivers takes place and picnics are held. There are numerous other festivals. The Tibetan calendar lags approximately four to six weeks behind the solar calendar.

Notes

- ↑ 西藏自治区; 青海省; 四川省; 云南省; 甘肃省 (行政区划网). Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 China-India Border: Eastern Sector (map produced by the United States Central Intelligence Agency; Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin). Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ↑ China-India Border: Western Sector (map produced by the United States Central Intelligence Agency; Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin). Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ↑ Kingdom of Bhutan (Bhutan Tourism Corporation Limited) Retrieved March 9, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, Charles. Duel in the Snows: The True Story of the Younghusband Mission to Lhasa. London: John Murray, 2004. ISBN 0719554276

- Bell, Charles. Tibet: Past & Present. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924. ISBN 978-8120604827

- Dowman, Keith. The power-places of Central Tibet: the pilgrim's guide. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1988. ISBN 0710213700

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1993. ISBN 8121505828

- Grunfeld, A. Tom. The Making of Modern Tibet. East Gate Books, 1996. ISBN 1563247135

- Gyatso, Palden. The Autobiography of a Tibetan Monk. New York, NY: Grove Press, 1997 ISBN 0802135749

- McKay, Alex. Tibet and the British Raj: The Frontier Cadre 1904-1947. London: Curzon, 1997. ISBN 0700706275

- Norbu, Thubten Jigme, and Colin Turnbull. Tibet: Its History, Religion and People. Penguin Books, 1972. ISBN 978-0140213829

- Samuel, Geoffrey. Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Smithsonian Institution, 1993. ISBN 1560982314

- Shakya, Tsering. The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1999. ISBN 0231118147

- Smith, Warren W., Jr. Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996. ISBN 0813331552

- Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization. Reprint: Stanford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0804708061

- Wang, Jiawei, and Nyima Gyaincain . The Historical Status of China's Tibet. China Intercontinental Press, 2000. ISBN 7801133048

- Wilson, Brandon. Yak Butter Blues: A Tibetan Trek of Faith. Heliographica, an imprint of Pilgrim's Tales, 2004. ISBN 1933037237

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

- Tibet Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Tibet Facts

- Tibet Timeline China Tibet Info

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Tibet history

- Geography_of_Tibet history

- History_of_Tibet history

- Zhang_Zhung history

- Dalai_Lama history

- Autonomous_areas_of_China history

- Central_Tibetan_Administration history

- Economy_of_Tibet history

- Tibetan_culture history

- Tibetan_art history

- Tibetan_Festivals history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.