Tertullian

| |

| Born: | 155 C.E. Carthage, Roman Empire |

|---|---|

| Died: | 220 C.E. (aged 64–65) Carthage, Roman Empire |

| Writing period: | Patristic age |

| Subject(s): | Soteriology, traducianism |

| Magnum opus: | Apologeticus |

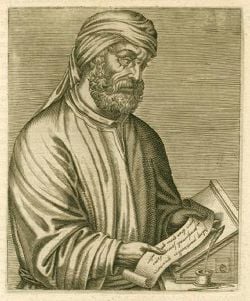

Tertullian (/tərˈtʌliən/; Latin: Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; c. 155 – c. 220 C.E.) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of Latin Christian literature. He was an early Christian apologist and a polemicist against heresy, including contemporary Christian Gnosticism.

Tertullian is the first Christian writer to use the term trinity, although his views on the relationship between God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit was not the orthodox position of the Catholic Church. He also held unorthodox views on a number of other topics, including the perpetual virginity of Mary. He promoted strict moral standards and celibacy not only for the priesthood but as the preferred lifestyle for spiritual growth.

Life

Scant reliable evidence exists regarding Tertullian's life. Most knowledge comes from passing references in his own writings. Roman Africa was famous as the home of orators. That influence can be seen in his writing style with its archaisms or provincialisms, its glowing imagery and its passionate temper. He was a scholar with an excellent education. He wrote at least three books in Koine Greek. In them, he refers to himself, but none of them are extant.

Some sources describe him as Berber.[1][2] The linguist René Braun suggested that he was of Punic origin but acknowledged that it is difficult to decide since the heritage of Carthage had become common to the Berbers.[3] Tertullian's own understanding of his ethnicity has been questioned. He referred to himself as Poenicum inter Romanos {Punic among Romans) in his book De Pallio[4] and claimed Africa as his patria.[3] According to church tradition, Tertullian was raised in Carthage and was thought to be the son of a Roman centurion. Tertullian is believed to have been a trained lawyer and an ordained priest. Those assertions rely on the accounts of Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History, II, ii. 4, and Jerome's De viris illustribus (On famous men) chapter 53.[5] Jerome claimed that Tertullian's father held the position of centurio proconsularis ("aide-de-camp") in the Roman army in Africa.(Jerome, Chronicon 16.23–24.)

Based on his use of legal analogies and on an identification of him with the jurist Tertullianus, who is quoted in the PandectsTertullian has been thought to be a lawyer. Although Tertullian used a knowledge of Roman law in his writings, his legal knowledge does not demonstrably exceed what could be expected from a sufficient Roman education.[6] The writings of Tertullianus, a lawyer of the same cognomen, exist only in fragments and do not explicitly denote a Christian authorship. Finally, any notion that Tertullian was a priest is also questionable. In his extant writings, he never describes himself as ordained in the church[6] and seems to place himself among the laity in his De Exhortatione Castitatis 7.3 and De Monogamia 12.2.

His conversion to Christianity perhaps took place about 197–198 C.E. (cf. Adolf Harnack, Bonwetsch, and others), but its immediate antecedents are unknown except as they are conjectured from his writings. The event must have been sudden and decisive, transforming at once his own personality. He writes that he could not imagine a truly Christian life without such a conscious breach, a radical act of conversion: "Christians are made, not born" (Apol., xviii). Two books addressed to his wife confirm that he was married to a Christian wife.[7]

In his middle life (about 207 C.E.), he was attracted to the "New Prophecy" of Montanism, but today most scholars reject the assertion that Tertullian left the mainstream church or was excommunicated.[8] "[W]e are left to ask whether Saint Cyprian could have regarded Tertullian as his master if Tertullian had been a notorious schismatic. Since no ancient writer was more definite (if not indeed fanatical) on this subject of schism than Saint Cyprian, the question must surely be answered in the negative."[9]

In the time of Augustine, a group of "Tertullianists" still had a basilica in Carthage, which within the same period passed to the Orthodox Church. It is unclear whether the name was merely another for the Montanists[10] or that it means that Tertullian later split with the Montanists and founded his own group.

Jerome[11] says that Tertullian lived to an old age. By the doctrinal works he published, Tertullian became the teacher of Cyprian and the predecessor of Augustine, who in turn became the chief founder of Latin theology.

Writings

General character

Thirty-one works are extant, together with fragments of others. Some fifteen works in Latin or Greek are lost, some as recently as the ninth century (De Paradiso, De superstitione saeculi, De carne et anima were all extant in the now damaged Codex Agobardinus in 814 C.E.). Tertullian's writings cover the whole theological field of the time – apologetics against paganism and Judaism, polemics, polity, discipline, and morals, or the whole reorganization of human life on a Christian basis. They gave a picture of the religious life and thought of the time which is of great interest to church historians.

Like other early Christian writers Tertullian used the term paganus to mean "civilian" as a contrast to the "soldiers of Christ."[12] The motif of Miles Christi did not assume the literal meaning of participation in war until Church doctrines justifying Christian participation in battle were developed around the fifth century.[13] In the second-century writings of Tertullian, paganus meant a "civilian" who was lacking self-discipline. In De Corona Militis XI.V he writes:[14]

| Apud hunc [Christum] tam miles est paganus fidelis quam paganus est miles fidelis. De Corona Militis XI.V) | With Him [Christ] the faithful citizen is a soldier, just as the faithful soldier is a citizen. (Ante-Nicene Fathers/Volume III/Apologetic/The Chaplet, or De Corona/Chapter XI|Ante-Nicene Fathers III, De Corona XI) |

Chronology and contents

The chronology of his writings is difficult to fix with certainty. It is in part determined by the Montanistic views that are set forth in some of them, by the author's own allusions to this writing, or that, as antedating others, and by definite historic data (e.g., the reference to the death of Septimius Severus, Ad Scapulam, iv). In his work against Marcion, which he calls his third composition on the Marcionite heresy, he gives its date as the fifteenth year of the reign of Severus (Adv. Marcionem, i.1, 15) – which would be approximately 208 C.E.

The writings may be divided into two periods of Tertullian's Christian activity, the mainstream and the Montanist, or according to their subject matter. The object of the former mode of division is to show, if possible, the change of views Tertullian's mind underwent. Using subject matter, the writings fall into two groups. Apologetic and polemic writings, like Apologeticus, De testimonio animae, the anti-Jewish Adversus Iudaeos, Adv. Marcionem, Adv. Praxeam, Adv. Hermogenem, De praescriptione hereticorum, and Scorpiace were written to counteract Gnosticism and other religious or philosophical doctrines. The other group consists of practical and disciplinary writings, e.g., De monogamia, Ad uxorem, De virginibus velandis, De cultu feminarum, De patientia, De pudicitia, De oratione, and Ad martyras.

Among his apologetic writings, the Apologeticus, addressed to the Roman magistrates, is a most powerful defense of Christianity and the Christians against the reproaches of the pagans, and an important legacy of the ancient Church, proclaiming the principle of freedom of religion as an inalienable human right and demanding a fair trial for Christians before they are condemned to death.

Tertullian was the first to disprove charges that Christians sacrificed infants at the celebration of the Lord's Supper and committed incest. He pointed to the commission of such crimes in the pagan world and then proved by the testimony of Pliny the Younger that Christians pledged themselves not to commit murder, adultery, or other crimes. He adduced the inhumanity of pagan customs such as feeding the flesh of gladiators to beasts. He argued that the gods have no existence and thus there is no pagan religion against which Christians may offend. Christians do not engage in the foolish worship of the emperors, that they do better: they pray for them, and that Christians can afford to be put to torture and to death, and the more they are cast down the more they grow; "the blood of the Christians is seed" (Apologeticum, 50). In the De Praescriptione he develops as its fundamental idea that, in a dispute between the Church and a separating party, the whole burden of proof lies with the latter, as the Church, in possession of the unbroken tradition, is by its very existence a guarantee of its truth.

The five books against Marcion, written in 207 C.E. or 208 C.E., are the most comprehensive and elaborate of his polemical works, invaluable for gauging the early Christian view of Gnosticism. Tertullian has been identified by Jo Ann McNamara as the person who originally invested the consecrated virgin as the "bride of Christ," which helped to bring the independent virgin under patriarchal rule.[15]

Manuscripts

The earliest manuscript (handwritten copy) of any of Tertullian's works dates to the eighth century, but most are from the fifteenth. There are five main collections of Tertullian's works, known as the Cluniacense, Corbeiense, Trecense, Agobardinum and Ottobonianus. Some of Tertullian's works are lost. All the manuscripts of the Corbeiense collection are also now lost, although the collection survives in early printed editions.[16]

Theology

Tertullian's theological views had a major impact on Western Christianity.

God

Tertullian reserves the appellation God, in the sense of the ultimate origin of all things, to the Father,[17] who made the world from nothing through his Son, the Word, and has corporeity though he is a spirit (De praescriptione, vii.; Adv. Praxeam, vii). However Tertullian used 'corporeal' only in the Stoic sense, to mean something with actual material existence, rather than the later idea of flesh.

Tertullian is often considered an early proponent of the Nicene doctrine, approaching the subject from the standpoint of the Logos doctrine, though he did not state the later doctrine of the immanent Trinity. In his treatise against Praxeas, who taught patripassianism in Rome, he used the words "trinity," "economy," (used in reference to the three persons) "persons," and "substance," maintaining the distinction of the Son from the Father as the unoriginate God, and the Spirit from both the Father and the Son (Adv. Praxeam, xxv). "These three are one substance, not one person; and it is said, 'I and my Father are one' in respect not of the singularity of number but the unity of the substance." The very names "Father" and "Son" indicate the distinction of personality. The Father is one, the Son is another, and the Spirit is another ("dico alium esse patrem et alium filium et alium spiritum" Adv. Praxeam, ix)), and (yet in defending the unity of God, he says the Son is not other ("alius a patre filius non est", (Adv. Prax. 18) as a result of receiving a portion of the Father's substance.[17] At times, speaking of the Father and the Son, Tertullian refers to "two gods."[17][18] ("Therefore," thou sayest, "if a god said and a god made, if one god said and another made, two gods are being preached.' If thou art so hard, think a little! And that thou mayest think more fully, accept that in the Psalm two gods are spoken of: 'Thy throne, God, is for ever, a sceptre of right direction is thy sceptre; thou hast loved justice and hast hated iniquity, therefore God, thy God, hath anointed thee.") Adv. Prax. 13 He says that all things of the Father belong also to the Son, including his names, such as Almighty God, Most High, Lord of Hosts, or King of Israel.

Though Tertullian considered the Father to be God (Yahweh), he responded to criticism of the Modalist Praxeas that this meant that Tertullian's Christianity was not monotheistic by noting that even though there was one God (Yahweh, who became the Father when the Son became his agent of creation), the Son could also be referred to as God, when referred to apart from the Father, because the Son, though subordinate to God, is entitled to be called God "from the unity of the Father" as he was formed from a portion of His substance.[17][19][20] Similarly J.N.D. Kelly stated: "Tertullian followed the Apologists in dating His 'perfect generation' from His extrapolation for the work of creation; prior to that moment God could not strictly be said to have had a Son, while after it the term 'Father', which for earlier theologians generally connoted God as author of reality, began to acquire the specialized meaning of Father of the Son."[21] As regards the subjects of subordination of the Son to the Father, the New Catholic Encyclopedia has commented: "In not a few areas of theology, Tertullian's views are, of course, completely unacceptable. Thus, for example, his teaching on the Trinity reveals a subordination of Son to Father that in the later crass form of Arianism the Church rejected as heretical."[22] Though he did not fully state the doctrine of the immanence of the Trinity, according to B. B. Warfield, he went a long distance in the way of approach to it.[20]

Apostolicity

Tertullian was a defender of the necessity of apostolicity. In his Prescription Against Heretics, he explicitly challenges heretics to produce evidence of the apostolic succession of their communities.[23]

Eucharist

Unlike many early Christian writers, Tertullian along with Clement of Alexandria used the word "figure" and "symbol" to define the Eucharist. In his book Against Marcion hw implied that: "this is my body" should be interpreted as "a figure of my body." While others have also suggested that he believed in a spiritual presence in the Eucharist.[24]

Baptism

Tertullian advises the postponement of baptism of little children and the unmarried, he mentions that it was customary to baptize infants, with sponsors speaking on their behalf.[25] He argued that an infant ran the risk of growing up and then falling into sin, which could cause them to lose their salvation, if they were baptized as infants.[26]

Contrary to early Syrian baptismal doctrine and practice, Tertullian describes baptism as a cleansing and preparation process which precedes the reception of the Holy Spirit in post-baptismal anointing (De Baptismo 6). De Baptismo includes the earliest known mention of a prayer for the consecration of the waters of baptism. This invocation may suggest a change in practice from baptizing in living (or running) water, where the Spirit was believed to be present, to baptizing in still water.[27]

Tertullian had an ex opere operato view of the baptism, thus the efficiency of baptism was not dependent upon the faith of the receiver.[26] He also believed that in an emergency, the laity can give the baptism.[8]

The Church

Tertullian interpreted that in Matthew 16:18–19 "the rock" refers to Peter. For him, Peter is the type of the one Church and its origins, this Church, is now present in a variety of local churches.[28] He also believed that the power to "bind and unbind" has passed from Peter to the apostles and prophets of the Montanist church, not the bishops. He mocked Pope Calixtus or Agrippinus (it is debated to whom he referred) when he challenged him on the Church forgiving capital sinners and letting them back into the church.[28] He believed that the people who committed grave sins, such as sorcery, fornication and murder, should not be let inside the church.[29]

As a Montanist, he attacked the church authorities as more interested in their own political power in the church than in listening to the Spirit. Tertullian's criticism of Church authorities has been compared to the Protestant reformation.[30]

Marriage

Tertullian's view of marriage was heavily influenced by Montanism; Tertullian's book Exhortation to Chastity, shows a huge shift in his views on marriage after becoming a Montanist. He had previously held marriage to be fundamentally good, but after his conversion he denied its goodness. He argues that marriage is considered to be good "when it is compared with the greatest of all evils." He argued that before the coming of Christ, the command to reproduce was a prophetic sign pointing to the coming of the Church; after it came, the command was superseded. He also believed lust for one's wife and for another woman were essentially the same, so that marital desire was similar to adulterous desire. He believed that sex even in marriage would disrupt the Christian life and that abstinence was the best way to achieve the clarity of the soul. Tertullian's views would later influence much of the western church.[31]

Tertullian was the first to introduce a view of "sexual hierarchy": he believed that those who abstain from sexual relations should have a higher hierarchy in the church than those who do not, because he saw sexual relations as a barrier that stopped one from a close relationship with God.[31]

Scripture

Tertullian did not have a specific listing of the canon, however, he quotes 1 John, 1 Peter, Jude, Revelation, the Pauline epistles and the four gospels. After Tertullian's conversion to Montanism, he also started to use the Shepherd of Hermas.[32] Tertullian made no references to the book of Tobit, but in his book Adversus Marcionem he quotes the book of Judith.[33] He quoted most of the Old Testament including many deuterocanonical books, however he never used the books of Chronicles, Ruth, Esther, 2 Maccabees, 2 John and 3 John.[34] He defended the Book of Enoch and he believed that the book was omitted by the Jews from the canon. He believed that the epistle to the Hebrews was made by Barnabas.[34] For Tertullian, scripture was authoritative; he used scripture as the primary source in almost every chapter of his every work, and very rarely anything else. He seems to prioritize the authority of scripture above anything else.[34]

When interpreting scripture, he would occasionally believe passages to be allegorical or symbolic, while in other places he would support a literal interpretation. He especially used allegorical interpretations about Christological prophecies of the Old Testament. He also included the belief of the simplicity of scripture: he believed that scripture interprets itself. Scripture must be interpreted in the light of a greater number of texts and they need to agree with each other.[34]

Other beliefs

Tertullian denied Mary's virginity in partu, and he was quoted by Helvidius in his debate with Jerome.[35] He held similar views as Antidicomarians. J. N. D. Kelly argued that Tertullian believed that Mary had imperfections, thus denying her sinlessness.[36]

Tertullian held to a view similar to the priesthood of all believers[37] and that the distinction between the clergy and the laity is only because of ecclesiastical institution. In an absence of a priest the laity can act as priests. His theory on the distinction of the laity and clergy is influenced by Montanism. His early writings do not have the same beliefs.[38]

He believed in Iconoclasm.[39]

He believed in historic premillennialism: that Christians will go through a period of tribulation, to be followed by a literal 1000-year reign of Christ.[40]

He attacked the use of Greek philosophy in Christian theology. For him, philosophy supported religious idolatry and heresy. He believed that many people became heretical because of relying on philosophy.[34] He stated "What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?"[3]

Tertullian's views of angels and demons were influenced by the Book of Enoch. He held that the Nephilim were born out of fallen angels who mingled with human women and had sexual relations. He believed that because of the actions of the watchers as described in the Book of Enoch, men would later judge angels.[41] He believed that angels are inferior to humans, and not made in the image of God. He believed that Angels are imperceptible to our senses, but they may choose to take on a human form or change shape.[42]

He taught fideistic concepts such as the later philosophers William of Ockham and Søren Kierkegaard.

Montanism

Tertullian was drawn to Montanism mainly because of its strict moral standards. He believed that the Church had forsaken the Christian way of life and entered a path of destruction. Montanism in North Africa seems to have been a reaction against secularism. The form of Montanism in North Africa seems to have differed from the views of Montanus, and thus the North African Montanists believed bishops to be successors of the apostles. They believed the New Testament to be the supreme authority on Christianity and did not deny most doctrines of the Church.

Tertullianists

Tertullianists were a group mentioned by Augustine, founded by Tertullian.[43] There exists differences of opinion on Tertullianists; Augustine seems to have believed that Tertullian, soon after joining the Montanists, started his own sect derived from Montanism, while some scholars believe that Augustine was in error, and that Tertullianists was simply an alternative name of North African Montanism and not a separate sect.[43]

Moral principles

Tertullian was an advocate of discipline and an austere code of practice. Like many of the African fathers, he was one of the leading representatives of the rigorist element in the early Church. His writings on public amusements, the veiling of virgins, the conduct of women, among others, reflect his austere views. His views may have led him to adopt Montanism with its ascetic rigor and its belief in chiliasm and the continuance of the prophetic gifts. Geoffrey D. Dunn believes that "Some of Tertullian's treatises reveal that he had much in common with Montanism ... To what extent, if at all, this meant that he joined a group that was schismatic (or, to put it another way, that he left the church) continues to be debated."[34]

On the principle that we should not look at or listen to what we have no right to practice, and that polluted things, seen and touched, pollute (De spectaculis, viii, xvii), he declared a Christian should abstain from the theater and the amphitheater, where pagan religious rites were applied and the names of pagan divinities invoked and the precepts of modesty, purity, and humanity were ignored or set aside, and where no place was offered to the onlookers for the cultivation of the Christian graces. Women should put aside their gold and precious stones as ornaments, (De cultu, v–vi) and virgins should conform to the law of St. Paul for women and keep themselves strictly veiled (De virginibus velandis). He praised the unmarried state as the highest (De monogamia, xvii; Ad uxorem, i.3) and called upon Christians not to allow themselves to be excelled in the virtue of celibacy by Vestal Virgins and Egyptian priests. He even labeled second marriage a species of adultery (De exhortatione castitatis, ix), but this directly contradicted the Epistles of the Apostle Paul. Tertullian's resolve to never marry again and that no one else should remarry eventually led to his break with Rome because the orthodox church refused to follow him in this resolve. He favored the Montanist sect that also condemned second marriage. One reason for Tertullian's disdain for marriage was his belief about the transformation that awaited a married couple. He believed that marital relations coarsened the body and spirit and would dull their spiritual senses and avert the Holy Spirit since husband and wife became one flesh once married.[15]

Tertullian has been criticized as misogynistic, on the basis of the contents of his De Cultu Feminarum, section I.I, part 2 (trans. C.W. Marx): "Do you not know that you are Eve? The judgment of God upon this sex lives on in this age; therefore, necessarily the guilt should live on also. You are the gateway of the devil; you are the one who unseals the curse of that tree, and you are the first one to turn your back on the divine law; you are the one who persuaded him whom the devil was not capable of corrupting; you easily destroyed the image of God, Adam. Because of what you deserve, that is, death, even the Son of God had to die."[44]

Critics like Amy Place notes that "Revisionist studies later rehabilitated" Tertullian.[44][45]

Tertullian had a radical view on the cosmos. He believed that heaven and earth intersected at many points and that it was possible that sexual relations with supernatural beings can occur.[46]

Works

Tertullian's writings are edited in volumes 1–2 of the Patrologia Latina, and modern texts exist in the Corpus Christianorum Latinorum. English translations by Sydney Thelwall and Philip Holmes can be found in volumes III and IV of the Ante-Nicene Fathers which are freely available online; more modern translations of some works are available.

- Apologetic

- Apologeticus pro Christianis.

- Libri duo ad Nationes.

- De Testimonio animae.

- Ad Martyres.

- De Spectaculis.

- De Idololatria.

- Accedit ad Scapulam liber.

- Dogmatic

- De Oratione.

- De Baptismo.

- De Poenitentia.

- De Patientia.

- Ad Uxorem libri duo.

- De Cultu Feminarum lib. II.

- Polemical

- De Praescriptionibus adversus Haereticos.

- De Corona Militis.

- De Fuga in Persecutione.

- Adversus Gnosticos Scorpiace.

- Adversus Praxeam.

- Adversus Hermogenem.

- Adversus Marcionem libri V.

- Adversus Valentinianos.

- Adversus Judaeos.

- De Anima.

- De Carne Christi.

- De Resurrectione Carnis.

- On morality

- De velandis Virginibus.

- De Exhortatione Castitatis.

- De Monogamia.

- De Jejuniis.

- De Pudicitia.

- De Pallio.

Possible chronology

The following chronological ordering was proposed by John Kaye, Bishop of Lincoln in the nineteenth century:[47]

Probably mainstream (Pre-Montanist):

- 1. De Poenitentia (On Repentance)

- 2. De Oratione (On Prayer)

- 3. De Baptismo (On Baptism)

- 4, 5. Ad Uxorem, lib. I & II, (To His Wife)

- 6. Ad Martyras (To the Martyrs)

- 7. De Patientia (On Patience)

- 8. Adversus Judaeos (Against the Jews)

- 9. De Praescriptione Haereticorum (On the Prescription of Heretics)

Indeterminate:

- 10. Apologeticus pro Christianis (Apology for the Christians)

- 11, 12. ad Nationes, lib. I & II (To the Nations)

- 13. De Testimonio animae (On the Witness of the Soul)

- 14. De Pallio (On the Ascetic Mantle)

- 15. Adversus Hermogenem (Against Hermogenes)

Probably Post-Montanist:

- 16. Adversus Valentinianus (Against the Valentinians)

- 17. ad Scapulam (To Scapula, Proconsul of Africa)

- 18. De Spectaculis (On the Games)

- 19. De Idololatria (On Idolatry)

- 20, 21. De cultu Feminarum, lib. I & II (On Women's Dress)

Definitely Post-Montanist:

- 22. Adversus Marcionem, lib I (Against Marcion, Bk. I)

- 23. Adversus Marcionem, lib II

- 24. De Anima (On the Soul),

- 25. Adversus Marcionem, lib III

- 26. Adversus Marcionem, lib IV

- 27. De Carne Christi (On the Flesh of Christ)

- 28. De Resurrectione Carnis (On the Resurrection of Flesh)

- 29. Adversus Marcionem, lib V

- 30. Adversus Praxean (Against Praxeas)

- 31. Scorpiace (Antidote to Scorpion's Bite)

- 32. De Corona Militis (On the Soldier's Garland)

- 33. De velandis Virginibus (On Veiling Virgins)

- 34. De Exhortatione Castitatis (On Exhortation to Chastity)

- 35. De Fuga in Persecutione (On Flight in Persecution)

- 36. De Monogamia (On Monogamy)

- 37. De Jejuniis, adversus psychicos (On Fasting, against the materialists)

- 38. De Puditicia (On Modesty)

Spurious works

There have been many works attributed to Tertullian in the past which have since been determined to be almost definitely written by others. Nonetheless, since their actual authors remain uncertain, they continue to be published together in collections of Tertullian's works.

- 1 Adversus Omnes Haereses (Against all Heresies) – possibly by Victorinus of Pettau

- 2 De execrandis gentium diis (On the Execrable Gods of the Heathens)

- 3 Carmen adversus Marcionem (Poem against Marcion)

- 4 Carmen de Iona Propheta (Poem about the Prophet Jonas) – poss. Cyprianus Gallus

- 5 Carmen de Sodoma (Poem about Sodom) – possibly by Cyprianus Gallus

- 6 Carmen de Genesi (Poem about Genesis)

- 7 Carmen de Judicio Domini (Poem about the Judgment of the Lord)

The popular Passio SS. Perpetuae et Felicitatis (Martyrdom of SS. Perpetua and Felicitas), much of it presented as the personal diary of St. Perpetua, was once assumed to have been edited by Tertullian. That view is no longer widely held, and the work is usually published separately from Tertullian's own works.

Legacy

Tertullian has been called "the father of Latin Christianity,"[48] as well as "the founder of Western theology."[49]

Tertullian originated new theological concepts and advanced the development of early Church doctrine. He is perhaps most famous for being the first writer in Latin known to use the term trinity (Latin: trinitas).[50] Tertullian was never recognized as a saint by the Eastern or Western Catholic churches. Several of his teachings on issues such as the clear subordination of the Son and Spirit to the Father,[17][22] as well as his condemnation of remarriage for widows and of fleeing from religious persecution, contradict the doctrines of these traditions, and his later rejection of orthodoxy for Montanism has led these communions to refrain from considering him a Church father, despite his significant contributions as an ecclesiastical writer.[51]

Influence on Novatianism

The Novatians refused forgiveness to idolaters or for people who committed other heinous sins, and made much use of the works of Tertullian. Some Novatians even joined Montanists. The views of Novatian on the Trinity and Christology are also strongly influenced by Tertullian.[52]

Ronald E. Heine writes, "With Novatianism we return to the spirit of Tertullian, and the issue of Christian discipline.[52]

Notes

- ↑ André Berthier, L'Algérie et son passé: ouvrage illustré de 82 gravures en phototypie (Paris, FR: Picard, 1951, ISBN 978-2708401716), 25. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ Constance B. Hilliard, Intellectual Traditions of Pre-colonial Africa (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1998, ISBN 978-0070288980), 150. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 David E.Wilhite, Tertullian the African: An Anthropological Reading of Tertullian's Context and Identities (Berlin, DE: Walter de Gruyter, 2011, ISBN 978-3110926262), 134. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ Frances Margaret Young, Mark J. Edwards, and Paul M. Parvis, Other Greek Writers, John of Damascus and Beyond, the West to Hilary (Leuven, BE: Peeters Publishers, 2006, ISBN 978-9042918856), 358. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ See introduction to Timothy Barnes, Tertullian: A literary and historical study (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1971). however, Barnes retracted some of his positions in the 1985 revised edition.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Timothy Barnes, Tertullian: A literary and historical study ( Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0198143628) 11, 24, 27. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ "Book Written to His Wife," New Advent. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Todd D. Still and David E Wilhite, Tertullian and Paul (London, U.K.: A&C Black, 2012, ISBN 978-0567554116), 46, 176. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ↑ Douglas Powell, "Tertullianists and Cataphrygians," Vigiliae Christianae 29 (1975): 33–54. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ↑ The passage in Praedestinatus describing the Tertullianists suggests that might have been the case, as the Tertullianist minister obtains the use of a church in Rome on the grounds that the martyrs to whom it was dedicated were Montanists. However, the passage is very condensed and ambiguous.

- ↑ Jerome, "De viris illustribus," New Advent. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ↑ Ernest Weekley, Etymological Dictionary of English, s.v. "pagan."

- ↑ Wojciech Iwanczak, "Miles Christi: the medieval ideal of knighthood," Journal of the Australian Early Medieval Association 8 (2012): 77–92.

- ↑ Alan G. Cameron, The Last Pagans of Rome (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0199780914). Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Lisa M. Bitel and Felice Lifshitz, Gender and Christianity in medieval Europe: new perspectives (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0812240696), 17, 21. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ Tertullian, "The Text Tradition: An Introduction to and Overview of the Manuscripts," The Tertullian Project. Retrieved January 29, 2024. It contains a complete list of known surviving and lost manuscripts of Tertullian.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Dale Tuggy, "History of Trinitarian Doctrines," in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta (Stanford, CA: Stanford University, 2016). Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ "Ergo, inquis, si deus dixit et deus fecit, si alius deus dixit et alius fecit, duo dii praedicantur. Si tam durus es, puta interim. Et ut adhuc amplius hoc putes, accipe et in psalmo duos deos dictos: Thronus tuus, deus, in aevum, <virga directionis> virga regni tui; dilexisti iustitiam et odisti iniquitatem, propterea unxit te deus, deus tuus."

- ↑ "Si filium nolunt secundum a patre reputari ne secundus duos faciat deos dici, ostendimus etiam duos deos in scriptura relatos et duos dominos: et tamen ne de isto scandalizentur, rationem reddimus qua dei non duo dicantur nec domini sed qua pater et filius duo, et hoc non ex separatione substantiae sed ex dispositione, cum individuum et inseparatum filium a patre pronuntiamus, nec statu sed gradu alium, qui etsi deus dicatur quando nominatur singularis, non ideo duos deos faciat sed unum, hoc ipso quod et deus ex unitate patris vocari habeat." ("If they do not wish that the Son be considered second to the Father, lest being second he cause it to be said that there are two gods, we have also showed that two gods are related in Scripture, and two lords. And yet, let them not be scandalized by this – we give a reason why there are not said to be two gods nor lords but rather two as a Father and a Son. And this not from separation of substance but from disposition, since we pronounce the Son undivided and unseparated from the Father, other not in status but in grade, who although he is said to be God when mentioned by himself, does not therefore make two gods but one, by the fact that he is also entitled to be called God from the unity of the Father.")

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 B.B. Warfield, Princeton Theological Review (1906): 56, 159.

- ↑ J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines,, 2nd edition (New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1960), 112.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 W. Le Saint, "Tertullian," The New Catholic Encyclopedia volume 13 (Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Research, Inc., 2003, ISBN 978-0787640170), 837.

- ↑ Tertullian, The Prescription against Heretics: Chapter 32, trans. Peter Holmes, New Advent. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ↑ John Kaye, Works of John Kaye, Bishop of Lincoln: Miscellaneous works with memoir of the author (London, U.K.: Rivingtons, 1888), 154. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ↑ "The delay of baptism is preferable; principally, however, in the case of little children. For why is it necessary ... that the sponsors likewise should be thrust into danger? ... For no less cause must the unwedded also be deferred—in whom the ground of temptation is prepared, alike in such as never were wedded by means of their maturity, and in the widowed by means of their freedom—until they either marry, or else be more fully strengthened for continence." Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, Arthur Cleveland Coxe, and Philip Schaff (eds.), The Ante-Nicene Fathers: The Writings of the Fathers Down to A.D. 325, volume 3, Part III, Chapter 18, (Sheffield, U.K.: Christian Literature Company, 1885).

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Philip F. Esler, The Early Christian World (London, U.K. Routledge, 2002, ISBN 978-1134549191), 70. Retrieved January 15, 2024.

- ↑ Maxwell E. Johnson, The Rites of Christian Initiation: Their evolution and interpretation (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0814662151).

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 James Puglisi, How Can the Petrine Ministry Be a Service to the Unity of the Universal Church? (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2010, ISBN 978-0802848628), 36. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ Cristina Lledo Gomez, The Church as Woman and Mother: Historical and Theological Foundations (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2018, ISBN 978-1587686948), 79. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ Tertullian, Tertullian: The Montanists The Tertullian Project. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Steven Schafer, Marriage, Sex, and Procreation: Contemporary Revisions to Augustine's Theology of Marriage (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2019, ISBN 978-1532671821), 10. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ Lee Martin McDonald, The Formation of the Biblical Canon: Volume 2: The New Testament: Its Authority and Canonicity (London, U.K.: Bloomsbury, 2017, ISBN 978-0567668851), 80. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ Martin Hengel, Septuagint As Christian Scripture (London, U.K.: A&C Black, 2004, ISBN 978-0567082879), 117. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 34.5 Geoffrey D. Dunn, Tertullian (London, U.K.: Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0415282314), 4, 13. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ Douglas Wirth, Shivering Babe, Glorious Lord: The Nativity Stories in Christian Tradition (Nashville, TN: WestBow Press, 2016, ISBN 978-1512738711), 167-168. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ James White, Mary—Another Redeemer? (Bloomington, MN: Bethany House, 1998, ISBN 978-0764221026).

- ↑ Mark Ellingsen, African Christian Mothers and Fathers: Why They Matter for the Church Today (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2015, ISBN 978-1606085509), 59. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ "Hierarchy of the Early Church," Catholic Answers. Retrieved January 30, 2024. "The Hierarchy as an Ecclesiastical Institution.—(I) The utterance of Tertullian (De exhort. cast. vii), declaring that the difference between the priests and the laity was due to ecclesiastical institution, and that therefore any layman in the absence of a priest could offer sacrifice, baptize, and act as priest, is based on Montanistic theories and contradicts earlier teachings of Tertullian (e.g., De baptismo, xvii).

- ↑ Jeremy Dimmick, James Simpson, and Nicolette Zeeman, Images, Idolatry, and Iconoclasm in Late Medieval England: Textuality and the Visual Image (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0191541964), 40. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ Sung Wook Chung and David Mathewson, Models of Premillennialism (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2018, ISBN 978-1532637698), 12. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ Stanley E. Porter and Brook W. Pearson, Christian-Jewish Relations Through the Centuries (A&C Black, 2004, ISBN 978-0567041708), 109. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ Jeffrey Burton Russell, Satan: The Early Christian Tradition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0801494130), 96. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 William Tabbernee, Fake Prophecy and Polluted Sacraments: Ecclesiastical and Imperial Reactions to Montanism (Leiden, ND: Brill, 2007, ISBN 978-9004158191), 268. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Amy Place, "Fashioning the Female in the Early North African Church," in Textiles and Gender in Antiquity: From the Orient to the Mediterranean, eds. M. Harlow, C. Michel, and L. Quillien (London, U.K.: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, ISBN 978-1350141490), 260. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ B.H. Dunning, Specters of Paul: Sexual Difference in Early Christian Thought (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0812204353), 126. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ↑ Dyan Elliot, "Scholar Discusses the 'Bride of Christ' in the Early Church," Fordham University Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ↑ cf. J.Kaye, 1845, The Ecclesiastical History of the Second and Third Centuries. List here as reproduced in Rev. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, editors, 1867–1872, Ante-Nicene Christian Library: Translation of the Writings of the Fathers, Down to AD 325, Vol. 18, p. xii–xiii

- ↑ Andrew J. Ekonomou, Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes: Eastern influences on Rome and the papacy from Gregory the Great to Zacharias, A.D. 590–752 (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2007, ISBN 978-0739133866), 22.

- ↑ Justo L. Gonzáles, "The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation," in The Story of Christianity, Vol. 1: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation (New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2010, ISBN 978-0061855887), 91–93.

- ↑ Marian Hillar, "Tertullian, Originator of the Trinity," in From Logos to Trinity: The Evolution of Religious Beliefs from Pythagoras to Tertullian (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-1139003971), 190–220.

- ↑ "Tertullian," Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "Novatian," Early Christian Writings. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barnes, Timothy. Tertullian: A literary and historical study. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1985 (original 1971). ISBN 978-0198143628

- Berthier, André. L'Algérie et son passé: ouvrage illustré de 82 gravures en phototypie. Paris, FR: Picard, 1951. ISBN 978-2708401716

- Bitel, Lisa M., and Felice Lifshitz. Gender and Christianity in medieval Europe: new perspectives. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0812240696

- Cameron, Alan G. The Last Pagans of Rome. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0199780914

- Chung, Sung Wook, and David Mathewson. Models of Premillennialism. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2018. ISBN 978-1532637698

- Dimmick, Jeremy James Simpson, and Nicolette Zeeman. Images, Idolatry, and Iconoclasm in Late Medieval England: Textuality and the Visual Image. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0191541964

- Dunn, Geoffrey D. Tertullian. London, U.K.: Psychology Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0415282314

- Dunning, B.H. Specters of Paul: Sexual Difference in Early Christian Thought. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0812204353

- Ekonomou, Andrew J. Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes: Eastern influences on Rome and the papacy from Gregory the Great to Zacharias, A.D. 590–752. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2007. ISBN 978-0739133866

- Ellingsen, Mark. African Christian Mothers and Fathers: Why They Matter for the Church Today. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2015. ISBN 978-1606085509

- Esler, Philip F. The Early Christian World. London, U.K. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 978-1134549191

- Gomez, Cristina Lledo. The Church as Woman and Mother: Historical and Theological Foundations. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2018. ISBN 978-1587686948

- Gonzáles, Justo L. "The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation," in The Story of Christianity, Vol. 1: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2010. ISBN 978-0061855887

- Hillar, Marian. "Tertullian, Originator of the Trinity," in From Logos to Trinity: The Evolution of Religious Beliefs from Pythagoras to Tertullian. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1139003971

- Hilliard, Constance B. Intellectual Traditions of Pre-colonial Africa. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1998. ISBN 978-0070288980

- Johnson, Maxwell E. The rites of Christian initiation: their evolution and interpretation. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0814662151

- Kaye, John. Works of John Kaye, Bishop of Lincoln: Miscellaneous works with memoir of the author. London, U.K.: Rivingtons, 1888. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Doctrines,, 2nd edition. New York, NY: Harper and Row, 1960.

- Le Saint, W. "Tertullian," The New Catholic Encyclopedia volume 13. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Research, Inc., 2003. ISBN 978-0787640170

- McDonald, Lee Martin. The Formation of the Biblical Canon: Volume 2: The New Testament: Its Authority and Canonicity. London, U.K.: Bloomsbury, 2017. ISBN 978-0567668851

- Place, Amy. "Fashioning the Female in the Early North African Church,"] in Textiles and Gender in Antiquity: From the Orient to the Mediterranean edited by M. Harlow, C. Michel, and L. Quillien. London, U.K.: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020. ISBN 978-1350141490

- Porter, Stanley E., and Brook W. Pearson. Christian-Jewish Relations Through the Centuries. London, U.K.: A&C Black, 2004. ISBN 978-0567041708

- Puglisi, James. How Can the Petrine Ministry Be a Service to the Unity of the Universal Church?. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2010. ISBN 978-0802848628

- Roberts, Alexander, James Donaldson, Arthur Cleveland Coxe, and Philip Schaff (eds.). The Ante-Nicene Fathers: The Writings of the Fathers Down to A.D. 325. Sheffield, U.K.: Christian Literature Company, 1885

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton. Satan: The Early Christian Tradition. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0801494130

- Schafer, Steven. Marriage, Sex, and Procreation: Contemporary Revisions to Augustine's Theology of Marriage. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2019. ISBN 978-1532671821

- Still, Todd D., and David E Wilhite. Tertullian and Paul. London, U.K.: A&C Black, 2012. ISBN 978-0567554116

- Tabbernee, William. Fake Prophecy and Polluted Sacraments: Ecclesiastical and Imperial Reactions to Montanism. Leiden, ND: Brill, 2007. ISBN 978-9004158191

- White, James. Mary—Another Redeemer?. Bloomington, MN: Bethany House, 1998. ISBN 978-0764221026

- Wilhite, David E. Tertullian the African: An Anthropological Reading of Tertullian's Context and Identities. Berlin, DE: Walter de Gruyter, 2011. ISBN 978-3110926262

- Wirth, Douglas. Shivering Babe, Glorious Lord: The Nativity Stories in Christian Tradition. Nashville, TN: WestBow Press, 2016. ISBN 978-1512738711

- Young, Frances Margaret, Mark J. Edwards, and Paul M. Parvis. Other Greek Writers, John of Damascus and Beyond, the West to Hilary. Leuven, BE: Peeters Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-9042918856

Further reading

- Ames, Cecilia. "Roman Religion in the Vision of Tertullian," in A Companion to Roman Religion, edited by Jörg Rüpke. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell, 2007. ISBN 978-1405129435

- Dunn, Geoffrey D. Tertullian. New York, NY: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 978-0415282307.

- Hillar, Marian. From Logos to Trinity: The Evolution of Religious Beliefs from Pythagoras to Tertullian. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1107013308

- Otten, Willemien. "Views on Women in Early Christianity: Incarnational Hermeneutics in Tertullian and Augustine," in Hermeneutics, Scriptural Politics, and Human Rights: Between text and context. edited by Bas de Gaay Fortman, Kurt Martens, and M.A. Mohamed Salih. Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. ISBN 978-0230622234

- Osborn, Eric F. Tertullian, First Theologian of the West. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0521524957

- Rankin, David. Tertullian and the Church. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0521480673

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2024.

Primary sources

- Tertullian's works in many languages, including Latin, and English, www.intratext.com.

- English translations of all Tertullian's works can be found in Rev. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, editors, 1867–1872, Ante-Nicene Christian Library: Translation of the Writings of the Fathers, Down to AD 325, Edinburgh: T&T Clark: Vol. 7 (Tertullian's Against Marcion), Vol. 11(Tertullian's Treatises, Pt. 1), Vol. 15 (Tertullian's Treatises, Pt.2), Vol. 18 (Tertullian's Treatises, Pt. 3)

- Works by Tertullian at Perseus Digital Library

- "The Text Tradition: An Introduction to and Overview of the Manuscripts," The Tertullian Project.

- Tertullian: The Montanists The Tertullian Project.

- The Prescription against Heretics: Chapter 32, translated by Peter Holmes, New Advent.

Secondary sources

- EarlyChurch.org.uk Detailed bibliography and on-line articles.

- Jerome's On Famous Men Chapter 53 is devoted to Tertullian.

- The Tertullian Project, a site which provides all of Tertullian's works in Latin, translations in many languages, manuscripts etc.

- J. Kaye, Bishop of Lincoln (1845, third edition) The Ecclesiastical History of the Second and Third Centuries, illustrated from the writings of Tertullian. London: Rivington.

- "Novatian," Early Christian Writings.

- "Book Written to His Wife," New Advent.

- "Hierarchy of the Early Church," Catholic Answers.

- "Tertullian," Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Tuggy, Dale, "History of Trinitarian Doctrines," in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N.Zalta, Standord, CA: Stanford University, 2016.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.