Sparta

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sparta (Doric Σπάρτα; Attic Σπάρτη Spartē) was a city-state in ancient Greece, situated on the River Eurotas in the southern part of the Peloponnese. From c. 650 B.C.E., it rose to become the dominant military power in the region and as such was recognized as the overall leader of the combined Greek forces during the Greco-Persian Wars. Sparta owed its military efficiency to its social structure, unique in ancient Greece. The Spartans formed a minority in their own territory of Lakonia; all male citizens of Sparta were full-time soldiers; unskilled labor was performed by a much larger, heavily subjugated slave population known as Helots (Gr., "captives"), while skilled labor was provided by another group, the Perioikoi (Gr. "those who live round about"). Helots were the majority inhabitants of Sparta (over 80 percent of the population according to Herodotus (8, 28-29)). They were ritually humiliated. During the Crypteia (annual declaration of war against the helots), they could be legally killed by Spartan citizens. Between 431 and 404 B.C.E., Sparta was the principal enemy of Athens during the Peloponnesian War; however, by 362 B.C.E., Sparta's role as the dominant military power in Greece was over.

Laconophilia is the admiration of Sparta, which continues to fascinate Western culture.[1][2]

Names

Sparta was generally referred to by the ancient Greeks as Lakedaimon (Λακεδαίμων) or Lakedaimonia (Λακεδαιμωνία); these are the names commonly used in the works of Homer and the Athenian historians Herodotus and Thucydides. Herodotus uses only the former and in some passages seems to denote by it the ancient Greek citadel at Therapne, in contrast to the lower town of Sparta. The immediate area around the town of Sparta, the plateau east of the Taygetos mountains, was generally referred as Lakonia. This term was sometimes used to refer to all the regions under direct Spartan control, including Messenia.

In Greek mythology, Lakedaimon was a son of Zeus by the nymph Taygete. He married Sparta the daughter of Eurotas, by whom he became the father of Amyclas, Eurydice, and Asine. He was king of the country which he named after himself, naming the capital after his wife. He was believed to have built the sanctuary of the Charites, which stood between Sparta and Amyclae, and to have given to those divinities the names of Cleta and Phaenna. A shrine was erected to him in the neighborhood of Therapne.

Lacedaemon is now the name of a province in the modern Greek prefecture of Laconia.

History

Prehistory

The prehistory of Sparta is difficult to reconstruct, because the literary evidence is far removed in time from the events it describes and is also distorted by oral tradition.[3] However, the earliest certain evidence of human settlement in the region of Sparta consists of pottery dating from the Middle Neolithic period, found in the vicinity of Kouphovouno some two kilometers south-southwest of Sparta.[4] These are the earliest traces of the original Mycenaean Spartan civilization, as represented in Homer's Iliad.

This civilization seems to have fallen into decline by the late Bronze Age, when Doric Greek warrior tribes from Epirus and Macedonia in northeast Greece came south to the Peloponnese and settled there.[5] The Dorians seem to have set about expanding the frontiers of Spartan territory almost before they had established their own state.[6] They fought against the Argive Dorians to the east and southeast, and also the Arcadian Achaeans to the northwest. The evidence suggests that Sparta, relatively inaccessible because of the topography of the Taygetan plain, was secure from early on: it was never fortified.[7]

Between the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E., the Spartans experienced a period of lawlessness and civil strife, later testified by both Herodotus and Thucydides.[8] As a result, they carried out a series of political and social reforms of their own society that they later attributed to a semi-mythical lawgiver, Lykourgos.[9] These reforms mark the beginning of the history of Classical Sparta.

Classical Sparta

In the Second Messenian War, Sparta established itself as a local power in Peloponnesus and the rest of Greece. During the following centuries, Sparta's reputation as a land-fighting force was unequaled.[10] In 480 B.C.E., a small force of Spartans, Thespians, and Thebans led by King Leonidas (approximately 300 were full Spartiates, 700 were Thespians, and 400 were Thebans; these numbers do not reflect casualties incurred prior to the final battle), made a legendary last stand at the Battle of Thermopylae against the massive Persian army, inflicting a very high casualty rate on the Persian forces before finally being encircled.[11] The superior weaponry, strategy, and bronze armor of the Greek hoplites and their phalanx again proved their worth one year later when Sparta assembled at full strength and led a Greek alliance against the Persians at the battle of Plataea.

The decisive Greek victory at Plataea put an end to the Greco-Persian War along with Persian ambition of expanding into Europe. Even though this war was won by a pan-Greek army, credit was given to Sparta, who besides being the protagonist at Thermopylae and Plataea, had been the de facto leader of the entire Greek expedition.

In later Classical times, Sparta along with Athens, Thebes and Persia had been the main powers fighting for supremacy against each other. As a result of the Peloponnesian War, Sparta, a traditionally continental culture, became a naval power. At the peak of its power, Sparta subdued many of the key Greek states and even managed to overpower the elite Athenian navy. By the end of the fifth century B.C.E., it stood out as a state which had defeated at war the Athenian Empire and had invaded Persia, a period which marks the Spartan Hegemony.

During the Corinthian War Sparta faced a coalition of the leading Greek states: Thebes, Athens, Corinth, and Argos. The alliance was initially backed by Persia, whose lands in Anatolia had been invaded by Sparta and which feared further Spartan expansion into Asia.[12] Sparta achieved a series of land victories, but many of her ships were destroyed at the battle of Cnidus by a Greek-Phoenician mercenary fleet that Persia had provided to Athens. The event severely damaged Sparta's naval power but did not end its aspirations of invading further into Persia, until Conon the Athenian ravaged the Spartan coastline and provoked the old Spartan fear of a helot revolt.[13]

After a few more years of fighting, the "King's peace" was established, according to which all Greek cities of Ionia would remain independent, and Persia would be free of the Spartan threat.[13] The effects of the war were to establish Persia's ability to interfere successfully in Greek politics and to affirm Sparta's hegemonic position in the Greek political system.[14] Sparta entered its long-term decline after a severe military defeat to Epaminondas of Thebes at the Battle of Leuctra. This was the first time that a Spartan army lost a land battle at full strength.

As Spartan citizenship was inherited by blood, Sparta started facing the problem of having a helot population vastly outnumbering its citizens.

Hellenistic and Roman Sparta

Sparta never fully recovered from the losses that the adult male Spartans suffered at Leuctra in 371 B.C.E. and the subsequent helot revolts. Nonetheless, it was able to limp along as a regional power for over two centuries. Neither Philip II nor his son Alexander the Great even attempted to conquer Sparta: it was too weak to be a major threat that needed to be eliminated, but Spartan martial skill was still such that any invasion would have risked potentially high losses. Even during her decline, Sparta never forgot its claims on being the "defender of Hellenism" and its Laconic wit. An anecdote has it that when Philip II sent a message to Sparta saying "If I enter Laconia, I will level Sparta to the ground," the Spartans responded with the single, terse reply: "If."[15]

Even when Philip created the league of the Greeks on the pretext of unifying Greece against Persia, Spartans were excluded of their own will. The Spartans, for their part, had no interest in joining a pan-Greek expedition if it was not under Spartan leadership. According to Herodotus, the Macedonians were a people of Dorian stock, akin to the Spartans, but that did not make any difference. Thus, upon the conquest of Persia, Alexander the Great sent to Athens 300 suits of Persian armour with the following inscription "Alexander son of Philip, and the Greeks—except the Spartans—from the barbarians living in Asia."[16]

During the Punic Wars, Sparta was an ally of the Roman Republic. Spartan political independence was put to an end when it was eventually forced into the Achaean League. In 146 B.C.E., Greece was conquered by the Roman general Lucius Mummius. During the Roman conquest, Spartans continued their way of life, and the city became a tourist attraction for the Roman elite who came to observe exotic Spartan customs. Supposedly, following the disaster that befell the Roman Imperial Army at the Battle of Adrianople (378 C.E.), a Spartan phalanx met and defeated a force of raiding Visigoths in battle.

Structure of Classical Spartan society

Constitution

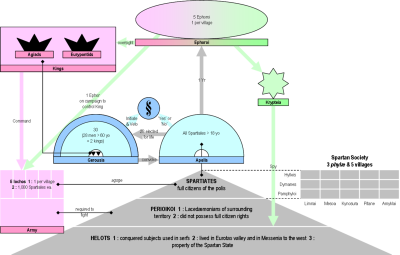

The Doric state of Sparta, copying the Doric Cretans, developed a mixed governmental state. The state was ruled by two hereditary kings of the Agiad and Eurypontids families,[17] both supposedly descendants of Heracles and equal in authority, so that one could not act against the veto of his colleague. The origins of the powers exercised by the assembly of the citizens are virtually unknown because of the lack of historical documentation and Spartan state secrecy.

The duties of the kings were primarily religious, judicial, and militaristic. They were the chief priests of the state and also maintained communication with the Delphian sanctuary, which always exercised great authority in Spartan politics. In the time of Herodotus (about 450 B.C.E.), their judicial functions had been restricted to cases dealing with heiresses, adoptions and the public roads. Civil and criminal cases were decided by a group of officials known as the ephors, as well as a council of elders known as the Gerousia. The Gerousia consisted of 28 elders over the age of 60, elected for life and usually part of the royal households, and the two kings.[18] High state policy decisions were discussed by this council who could then propose action alternatives to the Damos, the collective body of Spartan citizenry, who would select one of the alternatives by voting.[19][20]

Aristotle describes the kingship at Sparta as "a kind of unlimited and perpetual generalship" (Pol. iii. I285a), while Isocrates refers to the Spartans as "subject to an oligarchy at home, to a kingship on campaign" (iii. 24). Here also, however, the royal prerogatives were curtailed over time. Dating from the period of the Persian wars, the king lost the right to declare war and was accompanied in the field by two ephors. He was supplanted also by the ephors in the control of foreign policy.

Over time, the kings became mere figure-heads except in their capacity as generals. Real power was transferred to the ephors ("officials") and to the Gerousia ("Council of elders").

Citizenship

Not all inhabitants of the Spartan state were considered to be citizens. Only those who had undertaken the Spartan education process known as the agoge were eligible. However, usually the only people eligible to receive the agoge were Spartiates, or people who could trace their ancestry to the original inhabitants of the city.

There were two exceptions: (1) Trophimoi or "foster sons" were foreign students invited to study. For example, the Athenian general Xenophon, for example, sent his two sons to Sparta as trophimoi; (2) The other exception was that sons of helots could be enrolled as syntrophoi if a Spartiate formally adopted him and paid his way. If a syntrophos did exceptionally well in training, he might be sponsored to become a Spartiate.[21]

Others in the state were the perioikoi, who can be described as civilians, and helots,[22] the state-owned serfs that made up a large majority of the population. Because descendants of non-Spartan citizens were not able to follow the agoge, and because Spartans who could not afford to pay the expenses of the agoge could lose their citizenship, the Spartan society suffered over time from constantly declining manpower.

Helots and Perioikoi

Helots

The Spartans were a minority of the Lakonian population. By far the largest class of inhabitants were the helots (in Classical Greek Εἵλωτες / Heílôtes).[23][24]

The helots were originally free Greeks from the areas of Messenia and Lakonia whom the Spartans had defeated in battle and subsequently enslaved. In other Greek city-states, free citizens were part-time soldiers who, when not at war, carried on other trades. Since Spartan men were full-time soldiers, they were not available to carry out manual labor.[25] The helots were used as unskilled serfs, tilling Spartan land. Helot women were often used as wet nurses. Helots also travelled with the Spartan army as non-combatant serfs. At the last stand of the Battle of Thermopylae, the Greek dead included not just the legendary three hundred Spartan soldiers but also several hundred Thespian and Theban troops and a large number of helots.[26]

According to Myron of Priene[27] of the middle third century B.C.E.,

"They assign to the Helots every shameful task leading to disgrace. For they ordained that each one of them must wear a dogskin cap (κυνῆ / kunễ) and wrap himself in skins (διφθέρα / diphthéra) and receive a stipulated number of beatings every year regardless of any wrongdoing, so that they would never forget they were slaves. Moreover, if any exceeded the vigour proper to a slave's condition, they made death the penalty; and they allotted a punishment to those controlling them if they failed to rebuke those who were growing fat".[28]

Plutarch also states that Spartans treated the Helots "harshly and cruelly": they compelled them to drink pure wine (which was considered dangerous - wine usually being cut with water) "…and to lead them in that condition into their public halls, that the children might see what a sight a drunken man is; they made them to dance low dances, and sing ridiculous songs…" during syssitia (obligatory banquets).[29][30]

Helots did not have voting rights, although compared to non-Greek slaves in other parts of Greece they were relatively privileged. The Spartan poet Tyrtaios refers to Helots being allowed to marry.[31] They also seem to have been allowed to practice religious rites and, according to Thucydides, own a limited amount of personal property.[32]

Relations between the helots and their Spartan masters were hostile. Thucydides remarked that "Spartan policy is always mainly governed by the necessity of taking precautions against the helots."[33][34]

Each year when the Ephors took office they routinely declared war on the helots, thereby allowing Spartans to kill them without the risk of ritual pollution.[35] This seems to have been done by kryptes (sing. κρύπτης), graduates of the Agoge who took part in the mysterious institution known as the Krypteia (annual declaration of war against the helots).[36]

Around 424 B.C.E., the Spartans murdered two thousand helots in a carefully staged event. Thucydides states:

"The helots were invited by a proclamation to pick out those of their number who claimed to have most distinguished themselves against the enemy, in order that they might receive their freedom; the object being to test them, as it was thought that the first to claim their freedom would be the most high spirited and the most apt to rebel. As many as two thousand were selected accordingly, who crowned themselves and went round the temples, rejoicing in their new freedom. The Spartans, however, soon afterwards did away with them, and no one ever knew how each of them perished."[37][38]

Periokoi

The Perioikoi came from similar origins as the helots but occupied a somewhat different position in Spartan society. Although they did not enjoy full citizen-rights, they were free and not subjected to the same harsh treatment as the helots. The exact nature of their subjection to the Spartans is not clear, but they seem to have served partly as a kind of military reserve, partly as skilled craftsmen and partly as agents of foreign trade.[39] Although Peroikoic hoplites occasionally served with the Spartan army, notably at the Battle of Plataea, the most important function of the Peroikoi was almost certainly the manufacture and repair of armour and weapons.[40]

Economy

Spartan citizens were debarred by law from trade or manufacture, which consequently rested in the hands of the Perioikoi, and were forbidden (in theory) to possess either gold or silver. Spartan currency consisted of iron bars,[41] thus making thievery and foreign commerce very difficult and discouraging the accumulation of riches. Wealth was, in theory at least, derived entirely from landed property and consisted in the annual return made by the helots, who cultivated the plots of ground allotted to the Spartan citizens. But this attempt to equalize property proved a failure: from the earliest times, there were marked differences of wealth within the state, and these became even more serious after the law of Epitadeus, passed at some time after the Peloponnesian War, removed the legal prohibition of the gift or bequest of land.[42]

Full citizens, released from any economic activity, were given a piece of land that was cultivated and run by the helots. As time went on, greater portions of land were concentrated in the hands of large landholders, but the number of full citizens declined. Citizens had numbered 10,000 at the beginning of the fifth century B.C.E. but had decreased by Aristotle's day (384–322 B.C.E.) to less than 1000, and had further decreased to 700 at the accession of Agis IV in 244 B.C.E. Attempts were made to remedy this situation by creating new laws. Certain penalties were imposed upon those who remained unmarried or who married too late in life. These laws, however, came too late and were ineffective in reversing the trend.

Life in Classical Sparta

Birth and death

Sparta was above all a militarist state, and emphasis on military fitness began virtually at birth. Shortly after birth, the mother of the child bathed it in wine to see whether the child was strong. If the child survived it was brought before the Gerousia by the child's father. The Gerousia then decided whether it was to be reared or not. If they considered it "puny and deformed," the baby was thrown into a chasm on Mount Taygetos known euphemistically as the Apothetae (Gr., ἀποθέτας, "Deposits").[43][44] This was, in effect, a primitive form of eugenics.[45]

There is some evidence that the exposure of unwanted children was practiced in other Greek regions, including Athens.[46]

When Spartans died, marked headstones would only be granted to soldiers who died in combat during a victorious campaign or women who died either in service of a divine office or in childbirth.

Education

When male Spartans began military training at age seven, they would enter the Agoge system. The Agoge was designed to encourage discipline and physical toughness and to emphasise the importance of the Spartan state. Boys lived in communal messes and were deliberately underfed, to encourage them to master the skill of stealing food. Besides physical and weapons training, boys studied reading, writing, music and dancing. Special punishments were imposed if boys failed to answer questions sufficiently 'laconically' (i.e. briefly and wittily).[47] At the age of 12, the Agoge obliged Spartan boys to take an older male mentor, usually an unmarried young man. The older man was expected to function as a kind of substitute father and role model to his junior partner; however, it is also reasonably certain that they had sexual relations (the exact nature of Spartan pederasty is not entirely clear).[48]

At the age of 18, Spartan boys became reserve members of the Spartan army. On leaving the Agoge they would be sorted into groups, whereupon some were sent into the countryside with only a knife and forced to survive on their skills and cunning. This was called the Krypteia, and the immediate object of it was to seek out and kill any helots as part of the larger program of terrorizing and intimidating the helot population.[49]

Less information is available about the education of Spartan girls, but they seem to have gone through a fairly extensive formal educational cycle, broadly similar to that of the boys but with less emphasis on military training. In this respect, classical Sparta was unique in ancient Greece. In no other city-state did women receive any kind of formal education.[50]

Military life

At age 20, the Spartan citizen began his membership in one of the syssitia (dining messes or clubs), comprised of about 15 members each, of which every citizen was required to be a member. Here each group learned how to bond and rely on one another. The Spartan exercised the full rights and duties of a citizen at the age of 30. Only native Spartans were considered full citizens and were obliged to undergo the training as prescribed by law, as well as participate in and contribute financially to one of the syssitia.[51]

Spartan men remained in the active reserve until age 60. Men were encouraged to marry at age 20 but could not live with their families until they left their active military service at age 30. They called themselves "homoioi" (equals), pointing to their common lifestyle and the discipline of the phalanx, which demanded that no soldier be superior to his comrades.[52] Insofar as hoplite warfare could be perfected, the Spartans did so.[53]

Thucydides reports that when a Spartan man went to war, their wife (or another woman of some significance) would customarily present them with their shield and say: "With this, or upon this" (Ἢ τὰν ἢ ἐπὶ τᾶς, Èi tàn èi èpì tàs), meaning that true Spartans could only return to Sparta either victorious (with their shield in hand) or dead (carried upon it).[54] If a Spartan hoplite were to return to Sparta alive and without his shield, it was assumed that he threw his shield at the enemy in an effort to flee; an act punishable by death or banishment. A soldier losing his helmet, breastplate or greaves (leg armour) was not similarly punished, as these items were personal pieces of armour designed to protect one man, whereas the shield not only protected the individual soldier but in the tightly packed Spartan phalanx was also instrumental in protecting the soldier to his left from harm. Thus the shield was symbolic of the individual soldier's subordination to his unit, his integral part in its success, and his solemn responsibility to his comrades in arms — messmates and friends, often close blood relations.

According to Aristotle, the Spartan military culture was actually short-sighted and ineffective. He observed:

It is the standards of civilized men not of beasts that must be kept in mind, for it is good men not beasts who are capable of real courage. Those like the Spartans who concentrate on the one and ignore the other in their education turn men into machines and in devoting themselves to one single aspect of city's life, end up making them inferior even in that.[55]

Even mothers enforced the militaristic lifestyle that Spartan men endured. There is a legend of a Spartan warrior who ran away from battle back to his mother. Although he expected protection from his mother, she acted quite the opposite. Instead of shielding her son from the shame of the state, she and some of her friends chased him around the streets, and beat him with sticks. Afterwards, he was forced to run up and down the hills of Sparta yelling his cowardliness and inferiority.[56][57]

Marriage

Spartan men were required to marry at age 30,[22] after completing the Krypteia.[58] Plutarch reports the peculiar customs associated with the Spartan wedding night:

The custom was to capture women for marriage (…) The so-called 'bridesmaid' took charge of the captured girl. She first shaved her head to the scalp, then dressed her in a man's cloak and sandals, and laid her down alone on a mattress in the dark. The bridegroom—who was not drunk and thus not impotent, but was sober as always—first had dinner in the messes, then would slip in, undo her belt, lift her and carry her to the bed.[59]

The husband continued to visit his wife in secret for some time after the marriage. These customs, unique to the Spartans, have been interpreted in various ways. The "abduction" may have served to ward off the evil eye, and the cutting of the wife's hair was perhaps part of a rite of passage that signalled her entrance into a new life.[60]

Role of women

Political, social, and economic equality

Spartan women enjoyed a status, power and respect that was unknown in the rest of the classical world. They controlled their own properties, as well as the properties of male relatives who were away with the army. It is estimated that women were the sole owners of at least 35 percent of all land and property in Sparta. The laws regarding a divorce were the same for both men and women. Unlike women in Athens, if a Spartan woman became the heiress of her father because she had no living brothers to inherit (an epikleros), the woman was not required to divorce her current spouse in order to marry her nearest paternal relative.[61] Spartan women rarely married before the age of 20, and unlike Athenian women who wore heavy, concealing clothes and were rarely seen outside the house, Spartan women wore short dresses and went where they pleased. Girls as well as boys exercised nude, and young women as well as young men may have participated in the Gymnopaedia ("Festival of Nude Youths").[62][63]

Women were able to negotiate with their husbands to bring their lovers into their homes. According to Plutarch in his Life of Lycurgus, men both allowed and encouraged their wives to bear the children of other men, because of the general communal ethos that made it more important to bear many progeny for the good of the city, than to be jealously concerned with one's own family unit. However, some historians argue that this 'wife sharing' was only reserved for elder males who had not yet produced an heir: "Despite these exceptions, and despite the report about wife sharing for reproductive purposes, the Spartans, like other Greeks, were monogamous."[22]

Historic women

Many women played a significant role in the history of Sparta. Queen Gorgo, heiress to the throne and the wife of Leonidas I, was an influential and well-documented figure.[64] Herodotus records that as a small girl she advised her father Cleomenes to resist a bribe. She was later said to be responsible for decoding a warning that the Persian forces were about to invade Greece; after Spartan generals could not decode a wooden tablet covered in wax, she ordered them to clear the wax, revealing the warning.[65] Plutarch's Moralia contains a collection of "Sayings of Spartan Women," including a laconic quip attributed to Gorgo: when asked by a woman from Attica why Spartan women were the only women in the world who could rule men, she replied: "Because we are the only women who are mothers of men." [66]

Archaeology

Thucydides wrote:

Suppose the city of Sparta to be deserted, and nothing left but the temples and the ground-plan, distant ages would be very unwilling to believe that the power of the Lacedaemonians was at all equal to their fame. Their city is not built continuously, and has no splendid temples or other edifices; it rather resembles a group of villages, like the ancient towns of Hellas, and would therefore make a poor show.[67]

Until the early twentieth century, the chief ancient buildings at Sparta were the theatre, of which, however, little showed above ground except portions of the retaining walls; the so-called Tomb of Leonidas, a quadrangular building, perhaps a temple, constructed of immense blocks of stone and containing two chambers; the foundation of an ancient bridge over the Eurotas; the ruins of a circular structure; some remains of late Roman fortifications; several brick buildings and mosaic pavements.

The remaining archaeological wealth consisted of inscriptions, sculptures, and other objects collected in the local museum, founded by Stamatakis in 1872 (and enlarged in 1907). Partial excavation of the round building was undertaken in 1892 and 1893 by the American School at Athens. The structure has been since found to be a semicircular retaining wall of Hellenic origin that was partly restored during the Roman period.

In 1904, the British School at Athens began a thorough exploration of Laconia, and in the following year excavations were made at Thalamae, Geronthrae, and Angelona near Monemvasia. In 1906, excavations began in Sparta.

A small "circus" described by Leake proved to be a theatre-like building constructed soon after 200 C.E. around the altar and in front of the temple of Artemis Orthia. Here musical and gymnastic contests took place as well as the famous flogging ordeal (diamastigosis). The temple, which can be dated to the 2nd century B.C.E., rests on the foundation of an older temple of the sixth century, and close beside it were found the remains of a yet earlier temple, dating from the ninth or even the tenth century. The votive offerings in clay, amber, bronze, ivory and lead found in great profusion within the precinct range, dating from the 9th to the fourth centuries B.C.E., supply invaluable evidence for early Spartan art.

In 1907, the sanctuary of Athena "of the Brazen House" (Chalkioikos) was located on the acropolis immediately above the theatre, and though the actual temple is almost completely destroyed, the site has produced the longest extant archaic inscription of Laconia, numerous bronze nails and plates, and a considerable number of votive offerings. The Greek city-wall, built in successive stages from the fourth to the second century, was traced for a great part of its circuit, which measured 48 stades or nearly 10 km (Polyb. 1X. 21). The late Roman wall enclosing the acropolis, part of which probably dates from the years following the Gothic raid of 262 C.E., was also investigated. Besides the actual buildings discovered, a number of points were situated and mapped in a general study of Spartan topography, based upon the description of Pausanias. Excavations showed that the town of the Mycenaean Period was situated on the left bank of the Eurotas, a little to the south-east of Sparta. The settlement was roughly triangular in shape, with its apex pointed towards the north. Its area was approximately equal to that of the "newer" Sparta, but denudation has wreaked havoc with its buildings and nothing is left save ruined foundations and broken potsherds.

Laconophilia

Laconophilia is love or admiration of Sparta and of the Spartan culture or constitution. In ancient times "Many of the noblest and best of the Athenians always considered the Spartan state nearly as an ideal theory realized in practice."[68]

In the modern world, the adjective "Spartan" is used to imply simplicity, frugality, or avoidance of luxury and comfort. The Elizabethan English constitutionalist John Aylmer compared the mixed government of Tudor England with the Spartan republic, stating that "Lacedemonia [meaning Sparta], [was] the noblest and best city governed that ever was." He commended it as a model for England. The Swiss-French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau contrasted Sparta favorably with ancient Athens in his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, arguing that its austere constitution was preferable to the more cultured nature of Athenian life. Sparta was also used as a model of social purity by Revolutionary and Napoleonic France.[69]

Notes

- ↑ Paul Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia: A Regional History 1300 to 362 B.C.E., 2nd ed. (Oxford: Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0415262763), 255.

- ↑ Victor Ehrenberg, From Solon to Socrates: Greek History and Civilisation between the 6th and 5th centuries B.C.E., 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0415040248), 28.

- ↑ Cartledge, 2002, 65.

- ↑ Cartledge, 2002, 28.

- ↑ William G. G. Forrest, A History of Sparta, 950–192 B.C.E. (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1968, ISBN 0393004813), 24-27.

- ↑ Ehrenberg, 31.

- ↑ Ehrenberg, 31.

- ↑ Ehrenberg, 36.

- ↑ Ehrenberg, 33.

- ↑ David Cartwright, A Historical Commentary on Thucydides: A Companion to Rex Warner's Penguin Translation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997, ISBN 0472084194), 176.

- ↑ Peter Green, The Greco-Persian Wars, 2nd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998, ISBN 0520203135), 10.

- ↑ Matthew Bennett, Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare (Stackpole Books, 2001, ISBN 081172610X), 86.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 John Boardman, Jasper Griffin, and Oswyn Murray (eds.), The Oxford Illustrated History of Greece and the Hellenistic World (Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0192854380), 141.

- ↑ John V. A. Fine, The Ancient Greeks: A Critical History (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1985, ISBN 0674033140), 556-559.

- ↑ Norman Davies, Europe: A History (Harper Perennial, 1998, ISBN 0060974680).

- ↑ Nicholas G. L. Hammond, The Genius of Alexander the Great (The University of North Carolina Press, 1998, ISBN 0807847445), 69.

- ↑ Cartledge, 2002.

- ↑ Philip de Souza, Waldemar Heckel, Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones, and Victor Davis Hanson, The Greeks at War: From Athens to Alexander (Essential Histories Specials) (London: Osprey Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1841768561).

- ↑ Aristotle, Thomas Alan Sinclair, (ed.) and Trevor J. Saunders, (trans.), The Politics, rev. ed. (Penguin Classics, 1981, ISBN 0140444211).

- ↑ Leonard Whibley, A Companion to Greek Studies (1905) reprint ed. (Kessinger Publications, 2009, ISBN 1437490859).

- ↑ Anton Powell, The Greek World (Routledge History of the Ancient World) (Routledge, 1997, ISBN 0415170427).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Sarah B. Pomeroy, Stanley M. Burstein, Walter Donlan, and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts, Ancient Greece: A Political, Social and Cultural History second ed. (Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 019530800X).

- ↑ Herodotus (IX, 28–29)

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenica, III, 3, 5

- ↑ Cartledge, 2002, 140.

- ↑ Ehrenberg, 159.

- ↑ Plutarch, in Richard J.A. Talbert, (ed. & translator), On Sparta, 2nd ed., (London: Penguin Classics, 2005, ISBN 0140449434), 20.

- ↑ Apud Athenaeus, 14, 647d = FGH 106 F 2. Trans. by Cartledge, 305.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus in Parallel Lives Vol I. 28, 8-10. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ↑ Donald Jackson (trans.), The Constitution of the Lacedaemonians by Xenophon of Athens: A New Critical Edition with a Facing Page English Translation (Edwin Mellen Press Ltd., 2007, ISBN 0773455167), 30.

- ↑ M.L. West, Greek Lyric Poetry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 019954039X), 24.

- ↑ Cartledge, 2002, 141.

- ↑ Thucydides (4, 80); the Greek is ambiguous

- ↑ Cartledge, 2002, 211.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Lycurgus 28, 7.

- ↑ Anton Powell, Athens and Sparta: Constructing Greek Political and Social History from 478 B.C.E. (London: Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0415262801), 254.

- ↑ Thucydides, Book IV 80.4.

- ↑ Classical historian Anton Powell has recorded a similar story from 1980s El Salvador, Powell, 2001, 256.

- ↑ Cartledge, 2002, 153-155.

- ↑ Cartledge, 2002, 158, 178.

- ↑ Peter Roberts, Excel HSC Ancient History (Pascal Press, 2006, ISBN 1741251788).

- ↑ Alexander Fuks, Social Conflict in Ancient Greece (Brill Academic Publishers, 1984, ISBN 9652234664).

- ↑ Cartledge, 2001, 84.

- ↑ Plutarch, in Talbert, 20.

- ↑ Paul Cartledge, Spartan Reflections (London: Duckworth, 2001, ISBN 0715629662, 84.

- ↑ Richard Buxton (ed.), From Myth to Reason?: Studies in the Development of Greek Thought (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0199247528), 201.

- ↑ Cartledge, 2001, 85.

- ↑ Cartledge, 2001, 91-105.

- ↑ Cartledge, 2001, 88.

- ↑ Cartledge, 2001, 83-84.

- ↑ E. David, Aristophanes and Athenian Society of the Early Fourth Century B.C.E. (Brill Archive, 1984, ISBN 9004070621).

- ↑ Robert Cowley and Geoffrey Parker (eds.), The Readers Companion to Military History (Houghton Mifflin, 1996, ISBN 0395669693), 438.

- ↑ Frank E. Adcock, The Greek and Macedonian Art of War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1962, ISBN 0520000056), 8-9.

- ↑ Plutarch, in Frank Cole Babbitt, Moralia Vol. III. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931, ISBN 0674992709), 465.

- ↑ Forrest, 1968, 53.

- ↑ Sarah B. Pomeroy, Spartan Women (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0195130677).

- ↑ H.D.F. Kitto, The Greeks (Piscataway, NJ: Aldine Transaction, 2007, ISBN 020230910X).

- ↑ Derek Benjamin Heater, A Brief History of Citizenship (New York University Press, 2004, ISBN 0814736726).

- ↑ Plutarch, 2005, 18-19.

- ↑ Pomeroy, 2002, 42.

- ↑ Sarah B. Pomeroy, Goddess, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity reprint ed. (New York: Schocken Books, 1995, ISBN 080521030X), 60-62.

- ↑ Marcia Guttentag and Paul F. Secord, Too Many Women? The Sex Ration Question (Sage Publications, 1983, ISBN 0803919190)

- ↑ Pomeroy, 2002, 34.

- ↑ Brittani Barger, Gorgo of Sparta History of Royal Women, November 29, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ↑ Helena P. Schrader, "Scandalous" Spartan Women: Educated and Economically Empowered Sparta Reconsidered—Spartan Women. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ↑ Plutarch, 2004, 457

- ↑ Thucydides, i. 10.

- ↑ Mueller, Dorians II, 192

- ↑ Slavoj Žižek, The True Hollywood Left Lacan.com, 2006. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adcock, Frank E. The Greek and Macedonian Art of War. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1962. ISBN 0520000056

- Aristotle, and Thomas Alan Sinclair (ed.), Trevor J. Saunders (trans.). The Politics. rev. ed. Penguin Classics, 1981. ISBN 0140444211

- Bennett, Matthew. Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare. Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 081172610X

- Boardman, John, Jasper Griffin, and Oswyn Murray (eds.). The Oxford Illustrated History of Greece and the Hellenistic World. Oxford University Press, 1962. ISBN 0192854380

- Bradford, Ernle. Thermopylae: The Battle for the West. New York: Da Capo Press, 2004. ISBN 0306813602

- Buxton, Richard (ed.). From Myth to Reason?: Studies in the Development of Greek Thought. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0199247528

- Cartledge, Paul. Sparta and Lakonia: A Regional History 1300 to 362 B.C.E. 2nd ed. Oxford: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0415262763

- Cartledge, Paul. Spartan Reflections. London: Duckworth, 2001. ISBN 0715629662

- Cartledge, Paul, and Antony Spawforth, contributor. Hellenistic and Roman Sparta, 2nd ed. Oxford: Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0415262771

- Cartwright, David. A Historical Commentary on Thucydides: A Companion to Rex Warner's Penguin Translation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997. ISBN 0472084194

- Cowley, Robert, and Geoffrey Parker (eds.). The Readers Companion Military History. Houghton Mifflin, 1996. ISBN 0395669693

- David, E. Aristophanes and Athenian Society of the Early Fourth Century B.C.E. Brill Archive, 1984. ISBN 9004070621

- Davies, Norman. Europe: a History. Harper Perennial, 1998. ISBN 0060974680

- Ehrenberg, Victor. From Solon to Socrates: Greek History and Civilisation between the 6th and 5th centuries B.C.E., 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0415040248

- Fine, John V. A. The Ancient Greeks: A Critical History. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1985. ISBN 0674033140

- Forrest, William G. G. A History of Sparta, 950–192 B.C.E. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1968. ISBN 0393004813

- Fuks, Alexander. Social Conflict in Ancient Greece. Brill Academic Pub., 1984. ISBN 9652234664

- Green, Peter. The Greco-Persian Wars, 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. ISBN 0520203135

- Guttentag, Marcia, and Paul F. Secord. Too Many Women? The Sex Ration Question. Sage Publications, 1983. ISBN 0803919190

- Hammond, Nicholas G. L. The Genius of Alexander the Great. The University of North Carolina Press, 1998. ISBN 0807847445

- Heater, Derek Benjamin. A Brief History of Citizenship. New York Univ. Press, 2004. ISBN 0814736726

- Jackson, Donald, Translator. The Constitution of the Lacedaemonians by Xenophon of Athens: A New Critical Edition with a Facing Page English Translation. Edwin Mellen Press Ltd., 2007. ISBN 0773455167

- Kitto, H.D.F. The Greeks. Piscataway, NJ: Aldine Transaction, 2007. ISBN 020230910X

- Morris, Ian. Death-Ritual and Social Structure in Classical Antiquity. (Key Themes in Ancient History) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 0521376114

- Plutarch. In Richard J.A. Talbert, ed. & translator. On Sparta, 2nd ed., edited by Christopher Pelling. London: Penguin Classics, 2005. ISBN 0140449434

- Plutarch. In Frank Cole Babbitt. Moralia. Vol. III. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004. ISBN 0674992709

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. reprint ed. New York: Schocken Books, 1995. ISBN 080521030X

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. Spartan Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0195130677

- Pomeroy, Sarah B., Stanley M. Burstein, Walter Donlan, and Jennifer Tolbert Roberts. Ancient Greece: A Political, Social and Cultural History, second ed. Oxford University Press, USA, 2007. ISBN 019530800X

- Powell, Anton. Athens and Sparta: Constructing Greek Political and Social History from 478 B.C.E., 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0415262801

- Powell, Anton. The Greek World. (Routledge History of the Ancient World) Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0415170427

- Roberts, Peter. Excel HSC Ancient History. Pascal Press. ISBN 1741251788

- Souza, Philip de, Waldemar Heckel, Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones, and Victor Davis Hanson. The Greeks at War. London: Osprey Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1841768561

- Thompson, F. Hugh. The Archaeology of Greek and Roman Slavery. London: Duckworth, 2002. ISBN 0715631950

- Thucydides. In M.I. Finley, Rex Warner. History of the Peloponnesian War. London: Penguin Books, 1974. ISBN 0140440399

- West, M.L. Greek Lyric Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 019954039X

- Whibley, Leonard. A companion to Greek studies. reprint ed. Kessinger Publications, 2009. ISBN 1437490859

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved February 7, 2023.

- Sparti Town Laconia Greek Travel Pages

- Sparti Ancient city Laconia Greek Travel Pages

- Sparta Reconsidered - History, beliefs and culture of Ancient Sparta

- Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.