Slug

| Slug | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Limax maximus, an air-breathing land slug

| ||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||

|

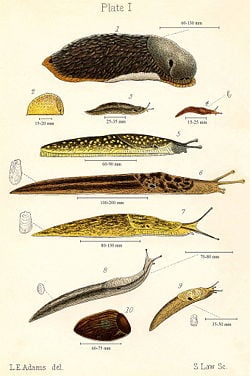

Slug is a common term for any snail-like gastropod mollusk in which the shell is absent, very reduced, or small and internal. Snail is the common name applied to most members of the mollusk class Gastropoda that have coiled shells. A slug is simply a snail without a shell, or in which the shell is an internal plate, or one in which the shell is external but reduced to very small size or a series of granules.

The term slug does not define a taxonomic grouping, but rather a nonscientific collection that includes members of various groups of snails, both marine and terrestrial. Most commonly, the term slug is applied to air-breathing land species.

The word "slug" or "sea slug" also is used for many marine species, almost all of which have gills. The largest group of marine shell-less gastropods or sea slugs are the nudibranchs. There are in addition many other groups of sea slug such as the heterobranch sea butterflies, sea angels, and sea hares, as well as the only very distantly related, pelagic, caenogastropod sea slugs, which are within the superfamily Carinarioidea. There is even an air-breathing sea slug, Onchidella.

This article is primarily about air-breathing (pulmonate) land slugs.

Slugs are important in food chains, consuming plant matter (including dead leaves) and fungus, and some species preying on earthworms and other gastropods, while being consumed by various amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and birds. Their main value to humans, beyond adding to the wonder of nature, is in their being vital to a healthy ecosystem, including helping to recycle decaying plant and fecal matter before it is lost. However, slugs also include a few agricultural and horticultural pest species and they can be damaging to commercial crops.

Overview

Most gastropods have a single shell, or valve, which is characteristically coiled or spiraled, as in snails, limpets, abalones, cowries, whelks, and conches. But Gastropoda is very diverse and many, such as slugs and sea slugs (nudibranches), lack shells; some even have shells with two halves, appearing as if bivalves.

Gastropods with coiled shells that are big enough to retract into commonly are called snails. The term snail itself is not a taxonomic unit but is variously defined to include all members of Gastropoda, all members of the subclass Orthogastropoda, all members of Orthogastropoda with a high coiled shell, or a group of gastropods with shells that do not include limpets, abalones, cowries, whelks, and conches. Land gastropods with a shell that is not quite vestigial, but is too small to retract into, (like many in the family Urocyclidae) are often known as "semislugs."

Slugs, which are gastropods that lack a conspicuous shell, are scattered throughout groups that primarily include "snails" and thus sometimes have been called "snails without shells" (Shetlar 1995).

Evolutionarily speaking, the loss or reduction of the shell in gastropods is a derived characteristic; the same basic body design has independently evolved many times, making slugs a strikingly polyphyletic group. In other words, the shell-less condition has arisen many times in the evolutionary past, and because of this, the various different taxonomic families of slugs, even just of land slugs, are not closely related to one another, despite a superficial similarity in the overall form of the body.

Land slugs

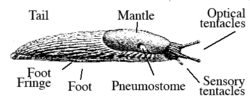

Land slugs, like all other gastropods, undergo torsion (a 180º twisting of the internal organs) during development. Internally, the anatomy of a slug clearly shows the effects of this rotation, but externally the bodies of slugs appear rather symmetrical, except for the positioning of the pneumostome, which is on one side of the animal, normally the right hand side.

The soft, slimy bodies of slugs are prone to desiccation, so land-living slugs are confined to moist environments and are forced to retreat to damp hiding places when the weather is dry.

Morphology and behavior

Like other snails, slugs macerate food using their radula, a rough, tongue-like organ with many tiny tooth-like denticles.

Like other pulmonate land snails, most slugs have two pairs of "feelers" or "tentacles" on their head; the upper pair being light sensors, while the lower pair provides the sense of smell. Both pairs are retractable and can be regrown if lost.

On top of the slug, behind the head, is the saddle-shaped mantle, and under this are the genital opening and anus. On one side (almost always the right hand side) of the mantle is a respiratory opening, which is easy to see when open, but difficult to see when closed. This opening is known as the pneumostome. Within the mantle in some species is a very small rather flat shell. Other species have a group of calcareous granules instead, which are the evolutionary remnants of a shell.

Like other snails, a slug moves by rhythmic waves of muscular contraction on the underside of its foot. It simultaneously secretes a layer of mucus on which it travels, which helps prevent damage to the tissues of the foot.

Some species of slugs hibernate underground during the winter in temperate climates, but in other species, the adults die in the autumn.

Mucus

Slugs' bodies are made up mostly of water, and without a full-sized shell to retreat into, their soft tissues are prone to desiccation. They must generate protective mucus to survive. Many species are most active after rain. In drier conditions, they hide in damp places under tree bark, fallen logs, rocks, and man-made structures such as planters and so forth, in order to help retain body moisture.

Slugs produce two types of mucus, one which is thin and watery, and another which is thick and sticky. Both kinds of mucus are hygroscopic (able to attract water molecules from the surrounding environment). The thin mucus is spread out from the center of the foot to the edges, whereas the thick mucus spreads out from front to back. They also produce thick mucus, which coats the whole body of the animal.

The mucus secreted by the foot contains fibers, which help prevent the slug from slipping down vertical surfaces. The "slime trail" that a slug leaves behind it has some secondary effects: other slugs coming across a slime trail can recognize others of the same species, which is useful in preparation to mating. Following a slime trail is also a necessary part of the hunting behavior of some carnivorous predatory slugs.

Body mucus provides some protection against predators, as it can make the slug hard to pick up and hold, for example in a bird's beak.

Some species of slug secrete slime cords to lower themselves onto the ground, or to suspend a pair of slugs during copulation.

Reproduction

Slugs, as with all land snails, are hermaphrodites, having both female and male reproductive organs.

Prior to reproduction, most land slugs will perform a ritual courtship before mating. Once a slug has located a mate, the pair may encircle each other, with the sperm exchanged through their protruded genitalia. A few days later a number of eggs are laid into a hole in the ground, or under the cover of objects such as fallen logs.

A commonly seen practice among many slugs is apophallation. Apophallation is a technique resorted to by some species of air-breathing land slugs such as Limax maximus and Ariolimax spp.. In these species of hermaphroditic terrestrial gastropod mollusks, after mating, if the slugs cannot successfully separate, a deliberate amputating of the penis takes place. The penis of these species is curled like a cork-screw and often becomes entangled in their mate's genitalia in the process of exchanging sperm. When all else fails, apophallation allows the slugs to separate themselves by one or both of the slugs chewing off the other's penis. Once its penis has been removed, a slug is still able to mate subsequently, but using only the female parts of its reproductive system.

Ecology

Many species of slugs play an important role in ecosystems by eating dead leaves, fungus, and decaying vegetable material. Other species eat parts of living plants.

Some slugs are predators, eating other slugs and snails, or earthworms.

Most slugs will on occasion also eat carrion, including dead of their own kind.

Predators

Frogs, toads, snakes, hedgehogs, Salamanders, eastern box turtles, humans, and also some birds and beetles are slug predators.

Slugs, when attacked, can contract their body, making themselves harder and more compact, and thus more difficult for many animals to grasp when combined with the slippery texture of the mucus that coats the animal. The unpleasant taste of the mucus is also a deterrent.

Human relevance

Most slugs are harmless to humans and their interests, but a small number of species of slugs are pests of agriculture and horticulture. They feed on fruits and vegetables prior to harvest, making holes in the crop, which can make individual items unsuitable to sell for aesthetic reasons and which can make the crop more vulnerable to rot and disease. Deroceras reticulatum is one example of a species of slug that has been widely introduced outside of its native range, and which is a serious pest to agriculture.

As control measures, special pesticides are used in large-scale agriculture, while small home gardens may use slug tape as a deterrent to keep slugs out of crop areas.

In a few rare cases, humans have contracted parasite-induced meningitis from eating raw slugs (Salleh 2003).

In rural southern Italy, the garden slug Arion hortensis is used to treat gastritis or stomach ulcer by swallowing it whole and alive. A clear mucous produced by the slug also is used to treat various skin conditions including dermatitis, warts, inflammations, calluses, acne and wounds (Quave et al. 2008).

The word "slug" is used in English as a metaphor for chosen inactivity, as in, "You lazy slug, you sat around and did nothing all day!"

Subinfraorders, superfamilies, and families

- Subinfraorder Orthurethra

- Superfamily Achatinelloidea Gulick, 1873

- Superfamily Cochlicopoidea Pilsbry, 1900

- Superfamily Partuloidea Pilsbry, 1900

- Superfamily Pupilloidea Turton, 1831

- Subinfraorder Sigmurethra

- Superfamily Acavoidea Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Achatinoidea Swainson, 1840

- Superfamily Aillyoidea Baker, 1960

- Superfamily Arionoidea J.E. Gray in Turnton, 1840

- Superfamily Athoracophoroidea

- Family Athoracophoridae

- Superfamily Orthalicoidea

- Subfamily Bulimulinae

- Superfamily Camaenoidea Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Clausilioidea Mörch, 1864

- Superfamily Dyakioidea Gude & Woodward, 1921

- Superfamily Gastrodontoidea Tryon, 1866

- Superfamily Helicoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Superfamily Helixarionoidea Bourguignat, 1877

- Superfamily Limacoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Superfamily Oleacinoidea H. & A. Adams, 1855

- Superfamily Orthalicoidea Albers-Martens, 1860

- Superfamily Plectopylidoidea Moellendorf, 1900

- Superfamily Polygyroidea Pilsbry, 1894

- Superfamily Punctoidea Morse, 1864

- Superfamily Rhytidoidea Pilsbry, 1893

- Family Rhytididae

- Superfamily Sagdidoidera Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Staffordioidea Thiele, 1931

- Superfamily Streptaxoidea J.E. Gray, 1806

- Superfamily Strophocheiloidea Thiele, 1926

- Superfamily Parmacelloidea

- Superfamily Zonitoidea Mörch, 1864

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Quave, C. L., A. Pieroni, and B. C. Bennett. 2008. Dermatological remedies in the traditional pharmacopoeia of Vulture-Alto Bradano, inland southern Italy. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 4: 5. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- Salleh, A. 2003. Man's brain infected by eating slugs. ABC October 20, 2003. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- Shetlar, D. J. 1995. Slugs and their management. Ohio State University Extension Fact Sheet. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.