Sandra Day O'Connor

| Sandra Day O'Connor | |

Official portrait, c. 2002 | |

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court

| |

| In office September 25 1981 – January 31 2006 | |

| Nominated by | Ronald Reagan |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | Potter Stewart |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Alito |

Judge of the Arizona Court of Appeals Template:Awrap

| |

| In office December 14, 1979 – September 25, 1981 | |

| Nominated by | Bruce Babbitt |

| Preceded by | Mary Schroeder |

| Succeeded by | Sarah D. Grant |

Judge of the Maricopa County Superior Court for Division 31

| |

| In office January 9, 1975 – December 14, 1979 | |

| Preceded by | David Perry |

| Succeeded by | Cecil Patterson |

Arizona State Senator

| |

| In office 1969 – 1975 | |

| Born | March 26 1930 El Paso, Texas |

| Died | December 1 2023 (aged 93) Phoenix, Arizona, U.S. |

| Spouse | John Jay O'Connor, III (m. 1952; died 2009) |

| Alma mater | Stanford University |

| Religion | Episcopalian |

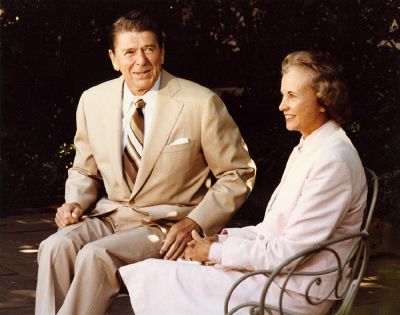

Sandra Day O'Connor (March 26, 1930 - December 1, 2023) was an American jurist who served as the first female Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1981 to 2006. Nominated to the Court by President Ronald Reagan she served for over 24 years. She announced her intention to retire on July 1, 2005, effective upon the confirmation of her successor. Justice Samuel Alito received confirmation and assumed office on January 31, 2006.

Due to her case-by-case approach to jurisprudence and her relatively moderate political views, O'Connor was the crucial swing vote of the Court for many of her final years on the bench. She remained active after her retirement, hearing cases on a part-time basis in federal district courts and courts of appeals as a visiting judge. She also organized conferences and gave speeches, advocating for judicial independence, various social issues that were important to her, and for the Rule of Law as the foundation of society.

During her term on the Court, O'Connor was regarded among the most powerful women in the world. In 2009, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama. The highlight of her legacy is undoubtedly her successful time serving as the first female justice on the Supreme Court, opening the way for women to attain the highest positions in society.

Life

Sandra Day was born on March 26, 1930, in El Paso, Texas, the daughter of Harry Alfred Day, a rancher, and Ada Mae (Wilkey).[1] She grew up on a 198,000-acre family cattle ranch near Duncan, Arizona and in El Paso where she attended school. Her home was nine miles from the nearest paved road,[2] and did not have running water or electricity until Sandra was seven years old.[3] As a youth she owned a .22-caliber rifle, and would shoot coyotes and jackrabbits.[2] She began driving as soon as she could see over the dashboard, and had to learn to change flat tires herself.[2]

Sandra had two younger siblings, a sister and a brother, respectively eight and ten years her junior.[3] Her sister Ann Day was a member of the Arizona Legislature from 1990 to 2000. Her brother was H. Alan Day, a lifelong rancher, with whom she wrote Lazy B: Growing up on a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest (2002), about their childhood experiences on the ranch.[4] For most of her early schooling, Sandra lived in El Paso with her maternal grandmother, and attended school at the Radford School for Girls, a private school, as the family ranch was very distant from any school, although Day was able to return to the ranch for holidays and the summer.[3] She graduated sixth in her class at Austin High School in El Paso in 1946.[5]

When she was 16 years old, Day enrolled at Stanford University[6] and later graduated magna cum laude with a B.A. in economics in 1950. She continued at Stanford Law School for her law degree in 1952.[7] There, she served on the Stanford Law Review whose then presiding editor-in-chief was future Supreme Court chief justice William Rehnquist. Day and Rehnquist dated in 1950.[8][6] The relationship ended upon Rehnquist's graduation and move to Washington, DC. However, in 1951, he proposed marriage in a letter, but Day did not accept the proposal (which was one of four she received while a student at Stanford).[6]

On December 20, 1952, six months after her graduation, she married John Jay O'Connor III at her family's ranch.[6]

When her husband was drafted, O'Connor decided to go with him to work in Germany as a civilian attorney for the Army's Quartermaster Corps. They remained there for three years before returning to the States where they settled in Maricopa County, Arizona, to begin their family. They had three sons: Scott (born 1958), Brian (born 1960), and Jay (born 1962).[9] Following Brian's birth, O'Connor took a five-year hiatus from the practice of law.[3]

Upon her appointment to the Supreme Court, O'Connor and her husband moved to the Kalorama area of Washington, D.C. The O'Connors became active in the Washington, D.C., social scene. O'Connor played tennis and golf in her spare time.[3] She was a baptized member of the Episcopal Church.[3]

O'Connor was successfully treated for breast cancer in 1988, and she also had her appendix removed that year.[10] That same year, John O'Connor left the Washington, D.C., law firm of Miller & Chevalier for a practice that required him to split his time between Washington, D.C., and Phoenix.[3]

Her husband suffered from Alzheimer's disease for nearly 20 years, until his death in 2009,[9] and she became involved in raising awareness of the disease. After retiring from the Court, O'Connor moved back to Phoenix, Arizona.[2]

Around 2013, O'Connor's friends and colleagues noticed that she was becoming more forgetful and less talkative.[6] By 2017, back problems led to her needing to use a wheelchair, and to her moving to an assisted living facility.[6] In October 2018, O'Connor announced her effective retirement from public life after disclosing that she had been diagnosed with the early stages of Alzheimer's-like dementia.[11]

On December 1, 2023, O'Connor died in Phoenix, aged 93, due to complications related to advanced dementia and a respiratory illness.[12]

Early career

In spite of her accomplishments at law school, no law firm in California was willing to hire her as a lawyer, although one firm did offer her a position as a legal secretary. She therefore turned to public service, taking a position as Deputy County Attorney of San Mateo County, California from 1952–1953 and as a civilian attorney for Quartermaster Market Center, Frankfurt, Germany from 1954–1957. From 1958–1960, she practiced law in the Maryvale area of the Phoenix metropolitan area, and served as Assistant Attorney General of Arizona from 1965–1969.

In 1969 she was appointed to the Arizona State Senate and was subsequently re-elected as a Republican to two two-year terms. In 1973, she became the first woman to serve as a state senate majority leader in any state. In 1975, she was elected judge of the Maricopa County Superior Court and served until 1979, when she was appointed to the Arizona Court of Appeals where she served for two years.[13]

Supreme Court career

Appointment

On July 7 1981, President Reagan, who had pledged during the 1980 presidential campaign to appoint the first woman to the Supreme Court, nominated her as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, replacing the retiring Potter Stewart.

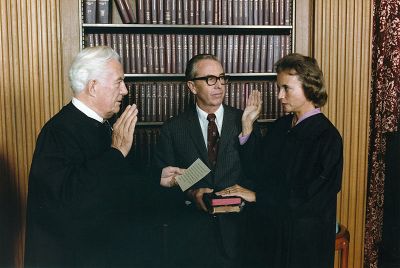

O'Connor's confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee began on September 9, 1981. It was the first televised confirmation hearing for a Supreme Court justice. The confirmation hearing lasted three days and largely focused on the issue of abortion. The Judiciary Committee approved O'Connor with seventeen votes in favor and one vote of present.

O'Connor was confirmed unanimously by the Senate on September 21 and took her seat September 25.

Presence on the Court

O'Connor said she felt a responsibility to demonstrate women could do the job of justice.[14] She faced some practical concerns, including the lack of a women's restroom near the Courtroom.[14] In her first year on the Court, O'Connor received over sixty thousand letters from the public, more than any other justice in history. She was unprepared for the scrutiny that came with being the first woman on the Court.

After being the lone woman on the court for 12 years, Ruth Bader Ginsburg became the second female Supreme Court justice in 1993. O'Connor said that she felt relief from the media clamor when she no longer was the only woman on the Court: "We just became two of the nine justices and it was just such a welcomed change, it was great."[15] O'Connor and Ginsburg were an unlikely pair but, strengthened by each other’s presence, their impact was immense:

They came from completely different backgrounds: Republican/Democrat, Goldwater Girl/liberal, Arizona/Brooklyn. ... But they were sisters in law. ... an unlikely pair came to nod at each other from the highest tribunal in America, as they finished the work of transforming the legal status of American women.[16]

Supreme Court jurisprudence

Initially, O'Connor's voting record aligned closely with the conservative William Rehnquist (voting with him 87 percent of the time during her first three years at the Court).[17] In nine of her first 16 years on the Court, O'Connor voted with Rehnquist more than with any other justice.[18]

Later on, as the Court's make-up became more conservative with Anthony Kennedy replacing Lewis Powell, and Clarence Thomas replacing Thurgood Marshall, O'Connor often became the swing vote on the Court. However, she usually disappointed the Court's more liberal bloc in contentious 5–4 decisions: from 1994 to 2004, she joined the traditional conservative bloc of Rehnquist, Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy, and Thomas 82 times; she joined the liberal bloc of John Paul Stevens, David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer only 28 times.[19]

O'Connor's relatively small shift away from conservatives on the Court seems to have been due at least in part to Thomas' views. When Thomas and O'Connor were voting on the same side, she would typically write a separate opinion of her own, refusing to join his. In the 1992 term, O'Connor did not join a single one of Thomas' dissents.[17]

Some notable cases in which O'Connor joined the majority in a 5–4 decision were:

- McConnell v. FEC, , upholding the constitutionality of most of the McCain-Feingold campaign-finance bill regulating "soft money" contributions.

- Grutter v. Bollinger, and Gratz v. Bollinger, , O'Connor wrote the opinion of the Court in Grutter and joined the majority in Gratz. In this pair of cases, the University of Michigan's undergraduate admissions program was held to have engaged in unconstitutional reverse discrimination, but the more limited type of affirmative action in the University of Michigan Law School's admissions program was held to have been constitutional.

- Lockyer v. Andrade, : O'Connor wrote the majority opinion, with the four conservative justices concurring, that a 50-year to life sentence without parole for petty shoplifting a few children's videotapes under California's three strikes law was not cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment because there was no "clearly established" law to that effect.

- Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, , O'Connor joined the majority holding that the use of school vouchers for religious schools did not violate the First Amendment's Establishment Clause.

- United States v. Lopez, : O'Connor joined a majority holding unconstitutional the Gun-Free School Zones Act as beyond Congress' Commerce Clause power.

- Bush v. Gore, , O'Connor joined with four other justices on December 12, 2000, to rule on the Bush v. Gore case that ceased challenges to the results of the 2000 presidential election (ruling to stop the ongoing Florida election recount and to allow no further recounts). This case effectively ended Al Gore's hopes to become president.

O'Connor played an important role in other notable cases, such as:

- Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, : This decision upheld as constitutional state restrictions on second trimester abortions that are not necessary to protect maternal health, contrary to the original trimester requirements in Roe v. Wade. Although O'Connor joined the majority, which also included Rehnquist, Scalia, Kennedy, and Byron White, in a concurring opinion she refused to explicitly overturn Roe.

On February 22, 2005, with Rehnquist and Stevens (who were senior to her) absent, she became the senior justice presiding over oral arguments in the case of Kelo v. City of New London and becoming the first woman to do so before the Court.

First Amendment

O'Connor was unpredictable in many of her court decisions, especially those regarding First Amendment Establishment Clause issues. O'Connor voted in favor of religious institutions, such as in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, Mitchell v. Helms, and Rosenberger v. University of Virginia. Conversely, in Lee v. Weisman she was part of the majority in the case that saw religious prayer and pressure to stand in silence at a graduation ceremony as part of a religious act that coerced people to support or participate in religion, which the Establishment Clause strictly prohibits. This is consistent with a similar case, Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, involving prayer at a school football game. In this case, O'Connor joined the majority opinion that stated prayer at school football games violates the Establishment Clause. In Lynch v. Donnelly, O'Connor signed onto a five-justice majority opinion holding that a nativity scene in a public Christmas display did not violate the First Amendment. She penned a concurrence in that case, opining that the crèche did not violate the Establishment Clause because it did not express an endorsement or disapproval of any religion.

Fourth Amendment

According to law professor Jeffrey Rosen:

O'Connor was an eloquent opponent of intrusive group searches that threatened privacy without increasing security. In a 1983 opinion upholding searches by drug-sniffing dogs, she recognized that a search is most likely to be considered constitutionally reasonable if it is very effective at discovering contraband without revealing innocent but embarrassing information.[20]

Washington College of Law professor Andrew Taslitz, referencing O'Connor's dissent in a 2001 case, said of her Fourth Amendment jurisprudence: "O'Connor recognizes that needless humiliation of an individual is an important factor in determining Fourth Amendment reasonableness."[21]

Cases involving race

In the 1990 and 1995 Missouri v. Jenkins rulings, O'Connor voted with the majority that district courts had no authority to require the state of Missouri to increase school funding to counteract racial inequality. In the 1991 case Freeman v. Pitts, O'Connor joined a concurring opinion in a plurality, agreeing that a school district that had formerly been under judicial review for racial segregation could be freed of this review, even though not all desegregation targets had been met. Law professor Herman Schwartz criticized these rulings, writing that in both cases "both the fact and effects of segregation were still present."[18]

In McCleskey v. Kemp in 1987, O'Connor joined a 5–4 majority that voted to uphold the death penalty for an African American man, Warren McCleskey, convicted of killing a white police officer, despite statistical evidence that Black defendants were more likely to receive the death penalty than others both in Georgia and in the U.S. as a whole.[18]

In 1996's Shaw v. Hunt and Shaw v. Reno, O'Connor joined a Rehnquist opinion, following an earlier precedent from an opinion she authored in 1993, in which the Court struck down an electoral districting plan designed to facilitate the election of two Black representatives out of 12 from North Carolina, a state that had not had any Black representative since Reconstruction, despite being approximately 20 percent Black.[18] The Court held that the districts were unacceptably gerrymandered and O'Connor called the odd shape of the district in question, North Carolina's 12th, "bizarre."[22]

Law professor Herman Schwartz called O'Connor "the Court's leader in its assault on racially oriented affirmative action,"[18] although she joined with the Court in upholding the constitutionality of race-based admissions to universities.[23]

In 2003, O'Connor authored a majority Supreme Court opinion (Grutter v. Bollinger) saying racial affirmative action "must have reasonable durational limits," suggesting an approximate limit of around 25 years.[24]

Abortion

In her confirmation hearings and early days on the Court, O'Connor was carefully ambiguous on the issue of abortion, as some conservatives questioned her anti-abortion credentials based on some of her votes in the Arizona legislature.[17]

O'Connor generally dissented from 1980s opinions which took an expansive view of Roe v. Wade; she criticized that decision's "trimester approach" sharply in her dissent in 1983's City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health. She criticized Roe in Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: "I dispute not only the wisdom but also the legitimacy of the Court's attempt to discredit and pre-empt state abortion regulation regardless of the interests it serves and the impact it has."[25] In 1989, O'Connor stated during the deliberations over the Webster case that she would not overrule Roe.[17] While on the Court, O'Connor did not vote to strike down any restrictions on abortion until Hodgson v. Minnesota in 1990.[25]

O'Connor allowed certain limits to be placed on access to abortion, but supported the right to abortion established by Roe. In Planned Parenthood v. Casey, O'Connor used a test she had originally developed in City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health to limit the holding of Roe v. Wade, opening up a legislative portal where a State could enact measures so long as they did not place an "undue burden" on a woman's right to an abortion. Casey revised downward the standard of scrutiny federal courts would apply to state abortion restrictions. However, it preserved Roe's core constitutional precept: that the Fourteenth Amendment implies and protects a woman's fundamental right to control the outcomes of her reproductive actions. Writing the plurality opinion for the Court, O'Connor, along with Kennedy and Souter, famously declared: At the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life. Beliefs about these matters could not define the attributes of personhood were they formed under compulsion of the State.[26]

Retirement

Justice O'Connor was successfully treated for breast cancer in 1988 (she also had her appendix removed that year). One side effect of this experience was that there was perennial speculation over the next seventeen years that she might retire from the Court.

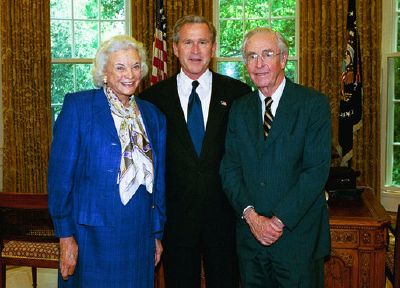

By 2005, the membership of the Supreme Court had been static for eleven years, the second longest period without a change in the Court's composition in American history. Chief Justice William Rehnquist was widely expected to be the first justice to retire during President George W. Bush's term, due to his age and his battle with cancer. However, on July 1, 2005 it was O'Connor who announced her retirement. In her letter to President Bush she stated that her retirement from active service would take effect upon the confirmation of her successor.

On July 19, President Bush nominated D.C. Circuit Judge John G. Roberts, Jr. to succeed Justice O'Connor, answering months of speculation as to Bush Supreme Court candidates. O'Connor felt he was an excellent and highly qualified choice—he had argued numerous cases before the Court during her tenure—but was somewhat disappointed her replacement was not a woman.

O'Connor had expected to leave the high court before the start of the next term on October 3, 2005. However, on September 3, Rehnquist died (O'Connor spoke at his funeral). Two days later, President Bush withdrew Roberts as his nominee for O'Connor's seat and instead appointed him to fill the vacant office of Chief Justice. O'Connor agreed to stay on the court until her replacement was confirmed. On October 3, President Bush nominated White House Counsel Harriet Miers to replace O'Connor. On October 27, Miers asked President Bush to withdraw her nomination; Bush accepted her request later the same day. On October 31, President Bush nominated Third Circuit Judge Samuel Alito to replace O'Connor; Alito was confirmed and sworn in on January 31, 2006.

Her last opinion, Ayotte v. Planned Parenthood of New England, written for a unanimous court, was a procedural decision that involved abortion.

She stated that after leaving the high court, she planned to travel, spend time with family, and, due to her fear of the attacks on judges by legislators, work with the American Bar Association on a commission to help explain the separation of powers and the role of judges. She also announced that she was working on a new book, which would focus on the early history of the Supreme Court.

She would have preferred to stay on the Supreme Court for several more years until she was ill and "really in bad shape" but stepped down to spend more time with her husband, who had been diagnosed with early stage Alzheimer's Disease. O'Connor, who was still physically and mentally fit, said it was her plan to follow the tradition of previous justices, who enjoy lifetime appointments: "Most of them get ill and are really in bad shape, which I would've done at the end of the day myself, I suppose, except my husband was ill and I needed to take action there."[27]

Post-Supreme Court

As a retired Supreme Court justice, O'Connor continued to receive a full salary, maintained a staffed office with at least one law clerk, and heard cases on a part-time basis in federal district courts and courts of appeals as a visiting judge.

She continued to speak and organize conferences on the issue of judicial independence.[12] During a March 2006 speech at Georgetown University, O'Connor said some political attacks on the independence of the courts pose a direct threat to the constitutional freedoms of Americans:

Any reform of the system is debatable as long as it is not motivated by retaliation for decisions that political leaders disagree with ... Courts interpret the law as it was written, not as the congressmen might have wished it was written. ... [I]t takes a lot of degeneration before a country falls into dictatorship, but we should avoid these ends by avoiding these beginnings."[28]

On May 15, 2006, O'Connor gave the commencement address at the William & Mary School of Law, where she encouraged graduates to do their part in the protection of American judicial independence:

Judicial independence doesn't happen all by itself. It's very hard to create and it's easier than most people imagine to destroy. And that's where you come in. We need lawyers to get out there and defend the concepts.[29]

She exhorted students at the opening of Elon University Law School to protect and promote the U.S. system of checks and balances, noting that “Judicial independence is a bedrock value of American government.”[30]

In October 2008, O'Connor spoke on racial equality in education at a conference hosted by the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School. Calling for the continuation of race-based affirmative action she noted:

Not enough progress has been made toward racial equality in education. ... Good education must be available to students of every race so they can get better jobs after school. ... Moreover, more focus needs to be placed on teaching children early on about ethnic diversity. Everyone benefits from learning how to interact and understand people from different backgrounds and races."[31]

Later in the conference, she was awarded the Charles Hamilton Houston Justice Award alongside Desmond Tutu and Dolores Huerta.

O'Connor reflected on her time on the Supreme Court by saying that she regretted the Court hearing the Bush v. Gore case in 2000 because it "stirred up the public" and "gave the Court a less-than-perfect reputation." She told the Chicago Tribune

Maybe the Court should have said, 'We're not going to take it, goodbye,' ... It turned out the election authorities in Florida hadn't done a real good job there and kind of messed it up. And probably the Supreme Court added to the problem at the end of the day.[32]

O'Connor was elected as an honorary fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration in 2005.[33] In October that year, O'Connor accepted the largely ceremonial role of becoming the 23rd Chancellor of the College of William & Mary. She continued in the role until 2012.[34]

The Sandra Day O'Connor Project on the State of the Judiciary, named for O'Connor, held annual conferences from 2006 through 2008 on the independence of the judiciary.[35]

In February 2009, O'Connor launched Our Courts, a website she created to offer interactive civics lessons to students and teachers because she was concerned about the lack of knowledge among most young Americans about how their government works. The initiative expanded, becoming iCivics in May 2010 offering free lesson plans, games, and interactive videogames for middle and high school educators.[36]

O'Connor served on the board of trustees of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, a museum dedicated to the U.S. Constitution. By November 2015, O'Connor had transitioned to being a trustee emeritus for the center.[37]

In 2009, O'Connor founded the 501(c)(3) non-profit organization now known as the Sandra Day O'Connor Institute. Its programs are dedicated to promoting civil discourse, civic engagement, and civics education.[38] In 2020, the Institute launched "Civics for Life," a multigenerational digital platform.[39]

In 2019, her former adobe residence in Arizona, curated by the O'Connor Institute, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[40]

Published works

- In 2002, O'Connor and her brother, H. Alan Day, co-authored Lazy B: Growing up on a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest, about their childhood experiences on the ranch.

- In 2003, O'Connor wrote The Majesty of the Law: Reflections of a Supreme Court Justice.

- In 2005, she wrote a children's book titled Chico, which gives an autobiographical description of her childhood with her horse "Chico."

- O'Connor wrote the 2013 book Out of Order: Stories from the History of the Supreme Court.

Legacy and honors

Justice O’Connor was a tireless advocate for judicial independence and the Rule of Law throughout the world. She is particularly remembered for being the first woman on the US Supreme Court, a duty she fulfilled successfully, responsibly reviewing cases and writing opinions and dissents eloquently. Her pioneering time on the Supreme Court laid a solid foundation for future women justices to serve, and for women to succeed in other positions in public service formerly held only by men.

After her death, tributes for O’Connor poured in from politicians and public figures, with many applauding her role as a trailblazer on the US supreme court. Chief Justice John Roberts called O'Connor "an eloquent advocate for civic education" and a "fiercely independent defender of the rule of law," noting in a public statement:

Sandra Day O’Connor blazed an historic trail as our nation’s first female justice. She met that challenge with undaunted determination, indisputable ability and engaging candor.[41]

President Joe Biden said she was an "American icon," whom he had encouraged to speak out on issues pertaining to women's rights:

“It is your right to go out and make speeches across the country about inequality for women — if you believe it. Don’t wall yourself off. Your male brethren have not done it. Don’t you do it. ... You are a singular asset. And you are looked at by many of us not merely because you are a bright, competent lawyer but also because you are a woman." [42]

iCivics board chairman Larry Kramer said that O'Connor was "kind and generous," emphasizing that “iCivics was her brainchild.” He stated:

She spotted the need and importance of reinvigorating civic education before others, and she led the creation of an innovative leader in the field. As important, she was kind and generous, a friend and mentor to countless young people.[41]

O'Connor was awarded many honors, including being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the US, by Barack Obama in 2009.

For her commitment to the ideals of "Duty, Honor, Country," she was awarded the prestigious Sylvanus Thayer Award by the United States Military Academy in 2005, becoming only the third woman to receive the award.

On April 5, 2006, Arizona State University renamed its law school the Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law in her honor.[43]

On May 22 2006, Yale University granted Justice O'Connor an honorary doctoral degree.

On September 19 2006, Justice O'Connor delivered the Dedication Address for the Elon University School of Law and accept an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree. Earlier that day, she delivered the Fall Convocation Address at Elon University, where she accepted a Doctor of Laws degree.

Notes

- ↑ Sandra Day O'Connor Fast Facts CNN (December 1, 2023). Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 John Heilpern, Out to Lunch with Sandra Day O’Connor Vanity Fair (March 20, 2013). Retrieved December 8. 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Marjorie Williams, How Sandra Day O'Connor became the most powerful woman in 1980s America The Washington Post (March 29, 2016). Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ↑ Sandra Day O'Connor and H. Alan Day, Lazy B: Growing Up on a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest. (New York: Random House, 2002, ISBN 0375507248).

- ↑ Trish Long, Radford's most famous alumna drops in for a talk El Paso Times (July 11, 2008).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Evan Thomas, First: Sandra Day O'Connor (New York: Random House, 2019, ISBN 978-0399589287).

- ↑ Kevin Cool, Front and Center Stanford Alumni Magazine (January 1, 2006). Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ↑ Joan Biskupic, Sandra Day O'Connor: How the First Woman on the Supreme Court became its most influential justice (New York: Harper Collins, 2005, ISBN 978-0060590185).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Adam Bernstein, John J. O'Connor III, 79; husband of Supreme Court justice The Washington Post (November 12, 2009). Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ↑ Linda Greenhouse, O'Connor Has Breast Surgery To Stop Cancer The New York Times (October 22, 1988). Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ↑ Matt Haag, Sandra Day O'Connor, First Woman on Supreme Court, Reveals Dementia Diagnosis The New York Times (October 23, 2018). Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Linda Greenhouse, Sandra Day O'Connor, First Woman on the Supreme Court, Is Dead at 93 The New York Times (December 1, 2023). Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ↑ Sandra Day O'Connor Oyez. Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 'Out Of Order' At The Court: O'Connor On Being The First Female Justice Fresh Air (March 5, 2013). Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- ↑ Nina Totenberg, From Triumph To Tragedy, 'First' Tells Story Of Justice Sandra Day O'Connor NPR (March 15, 2019). Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ↑ Linda Hirshman, Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World (Harper Perennial, 2016, ISBN 978-0062238474).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Jan Crawford Greenburg, Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court (Penguin Books, 2007, ISBN 978-1594201011).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Herman Schwartz, O'Connor as a 'Centrist'? Not When Minorities Are Involved Los Angeles Times (April 12, 1998). Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ↑ Robert J. Jackson Jr. and Thiruvendran Vignarajah, Nine Justices, Ten Years: A Statistical Retrospective Harvard Law Review 118(1) (2004): 521. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ↑ Jeffrey Rosen, The TSA is invasive, annoying – and unconstitutional The Washington Post (November 28, 2010). Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ↑ Andrew E. Taslitz, Reconstructing the Fourth Amendment: A History of Search and Seizure, 1789–1868 (NYU Press, 2009, ISBN 0814783260).

- ↑ Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) Justia. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ↑ James Taranto and Leonard Leo (eds.), Presidential Leadership: Rating the Best and the Worst in the White House (Free Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0743254335).

- ↑ Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003) Justia. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Linda Greenhouse, Becoming Justice Blackmun (Times Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0805077919).

- ↑ Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992) Justia. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ↑ Former Justice O'Connor: 'I Would Have Stayed Longer' News Max (February 5, 2007). Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ↑ Nina Totenberg, O'Connor Decries Republican Attacks on Courts NPR (March 10, 2006). Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Joe McClain, O'Connor urges law graduates to protect judicial independence W&M News Archive (May 12, 2008). Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Elon community mourns the death of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor Elon University News (December 1, 2023). Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Emily Dupraz, Affirmative action is still necessary, says O’Connor in HLS keynote address Harvard Law Today (Oct 27, 2008). Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Dahleen Glanton, O'Connor questions court's decision to take Bush v. Gore Chicago Tribune (April 27, 2013). Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Sandra Day O'Connor National Academy of Public Administration. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ Suzanne Clavet, Sandra Day O’Connor, 23rd Chancellor of William & Mary, remembered W&M News (December 1, 2023.

- ↑ Linda Greenhouse, Independence: why & from what? Daedalus 137(4) (Fall 2008): 5–7. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ About iCivics. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ Trustee Emeriti National Constitution Center. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ About Sandra Day O’Connor Institute for American Democracy. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ O'Connor U launched by Sandra Day O'Connor Institute Daily Independent (May 27, 2020). Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ Serena O'Sullivan, Sandra Day O'Connor's house in Tempe added to the National Register of Historic Places The Arizona Republic (July 20, 2019). Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Gloria Oladipo and Martin Pengelly, Sandra Day O'Connor, first woman to serve on US Supreme Court, dies aged 93 The Guardian (December 1, 2023). Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ↑ Olivia Alafriz, ‘American icon’: Biden pays tribute to Sandra Day O'Connor Politico (December 2, 2023). Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ↑ Eugene Scott, ASU welcomes O'Connor with renaming of law college Arizona Republic (April 6, 2006). Retrieved December 19, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Biskupic, Joan. Sandra Day O'Connor: How the First Woman on the Supreme Court became its most influential justice. New York: Harper Collins, 2005. ISBN 978-0060590185

- Greenburg, Jan Crawford. Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Control of the United States Supreme Court. Penguin Books, 2007. ISBN 978-1594201011

- Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. Times Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0805077919

- Hirshman, Linda. Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World. Harper Perennial, 2016. ISBN 978-0062238474

- O'Connor, Sandra Day. The Majesty of the Law: Reflections of a Supreme Court Justice. Random House, 2003). ISBN 978-0375509254

- O'Connor, Sandra Day. Chico. Dutton Juvenile, 2005. ISBN 978-0525474524

- O'Connor, Sandra Day. Out of Order: Stories from the History of the Supreme Court. Random House, 2013. ISBN 978-0812993929

- O'Connor, Sandra Day, and H. Alan Day. Lazy B: Growing Up on a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest. New York: Random House, 2002. ISBN 0375507248

- Taranto, James, and Leonard Leo (eds.). Presidential Leadership: Rating the Best and the Worst in the White House. Free Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0743254335

- Taslitz, Andrew E. Reconstructing the Fourth Amendment: A History of Search and Seizure, 1789–1868. NYU Press, 2009. ISBN 0814783260

- Thomas, Evan. First: Sandra Day O'Connor. New York: Random House, 2019. ISBN 978-0399589287

External links

All links retrieved December 1, 2023.

- Sandra Day O’Connor: First Woman on the Supreme Court Supreme Court of the United States

- Sandra Day O'Connor Oyez

| Preceded by: Potter Stewart |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States September 25, 1981 – January 31, 2006 |

Succeeded by: Samuel Alito |

| Preceded by: Samuel Alito |

United States order of precedence as of 2007 |

Succeeded by: Henry Paulson |

| The Burger Court |

| |

|---|---|---|

| Warren Earl Burger (1969–1986) | ||

| 1981–1986: | Wm. J. Brennan | B. White | T. Marshall | H. Blackmun | L.F. Powell, Jr. | Wm. Rehnquist | J.P. Stevens | S.D. O'Connor | |

| The Rehnquist Court | ||

| William Hubbs Rehnquist (1986–2005) | ||

| 1986–1987: | Wm. J. Brennan | B. White | T. Marshall | H. Blackmun | L.F. Powell, Jr. | J.P. Stevens | S.D. O'Connor | A. Scalia | |

| 1988–1990: | Wm. J. Brennan | B. White | T. Marshall | H. Blackmun | J.P. Stevens | S.D. O'Connor | A. Scalia | A. Kennedy | |

| 1990–1991: | B. White | T. Marshall | H. Blackmun | J.P. Stevens | S.D. O'Connor | A. Scalia | A. Kennedy | D. Souter | |

| 1991–1993: | B. White | H. Blackmun | J.P. Stevens | S.D. O'Connor | A. Scalia | A. Kennedy | D. Souter | C. Thomas | |

| 1993–1994: | H. Blackmun | J.P. Stevens | S.D. O'Connor | A. Scalia | A. Kennedy | D. Souter | C. Thomas | R.B. Ginsburg | |

| 1994–2005: | J.P. Stevens | S.D. O'Connor | A. Scalia | A. Kennedy | D. Souter | C. Thomas | R.B. Ginsburg | S. Breyer | |

| The Roberts Court | ||

| John Glover Roberts, Jr. (2005–current) | ||

| 2005–2006: | J.P. Stevens | S.D. O'Connor | A. Scalia | A. Kennedy | D. Souter | C. Thomas | R.B. Ginsburg | S. Breyer | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.