Sahel

The Sahel or Sahel Belt (from Arabic ساحل, sāḥil, shore, border or coast of the Sahara) is a semi-arid tropical savanna ecoregion in Africa, which forms the transitional zone between the Sahara Desert to the north and the more humid savanna belt to the south known as the Sudan (not to be confused with the country of the same name).

The Sahel stretches from the Atlantic Ocean on the west, eastward through northern Senegal, southern Mauritania, the great bend of the Niger River in Mali, Burkina Faso, southern Niger, northeastern Nigeria, south-central Chad, and through the nation of Sudan to the Red Sea coast.

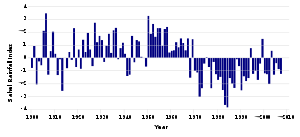

The Sahel region is one of primarily agriculture and pastoralism, which is negatively affected by periodic droughts and resultant famines. A catastrophic drought that lasted from the late 1960s to the early 1980s brought international attention to the area and prompted the formation of a number of agencies designed to combat both hunger and desertification.

Geography

The Sahel region of Africa runs 3862 kilometers (2,400 mi) from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east, in a belt that varies from several hundred to a thousand kilometers (620 miles) in width, covering an area of 3,053,200 square kilometers (1,178,847 sq mi). It is a transitional ecoregion of semi-arid grasslands, savannas, and thorn shrublands lying between the wooded Sudanian savanna to the south and the Sahara to the north.[1] The countries of the Sahel today include Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, and Eritrea.

The topography of the Sahel is mainly flat, and the region mostly lies between 200 and 400 meters (656-1313 ft) elevation. Several isolated plateaus and mountain ranges rise from the Sahel, but are designated as separate ecoregions because their flora and fauna are distinct from the surrounding lowlands.[1]

Over the history of Africa the region has been home to some of the most advanced kingdoms benefiting from trade across the desert. Collectively these states are known as the Sahelian kingdoms.

Climate

The Sahelian climate is tropical. Summers are hot, with maximum mean temperatures varying from 33° to 36°C (91° to 97°F). Monthly mean minimum temperatures fall in the range of 18° to 21°C (64° to 70°).

Rainfall in the southern area of the region is around 600 mm (23.6 inches). This decreases to around 200 mm (7.9 in) in the north. The rainy season lasts from May to September, followed by a six to eight month dry season. The dry season sees loss of leaves on the woody vegetation and drying grasses that may burn.

The quantity of rainfall is affected by the Intertropical Convergence Zone, a belt of low pressure girdling the Earth at the equator. When the zone penetrates far enough to the north, a long rainy season follows. If it fails to move sufficiently north, rainfall is limited.

During the winter months (the end of November to the middle of March), the harmattan, a dry and dusty West African trade wind, blows down from the north. On its passage over the desert it picks up fine dust particles (between 0.5 and 10 micrometers), delivering them to the Sahel.

Flora and fauna

The Sahel is mostly covered in grassland and savanna, with areas of woodland and shrubland. Grass cover is fairly continuous across the region, dominated by annual grass species such as Cenchrus biflorus, Schoenefeldia gracilis, and Aristida stipoides. Species of Acacia are the dominant trees, with Acacia tortilis the most common, along with Acacia senegal and Acacia laeta. Other tree species include Commiphora africana, Balanites aegyptiaca, Faidherbia albida, and Boscia senegalensis. In the northern part of the Sahel, areas of desert shrub, including Panicum turgidum and Aristida sieberana, alternate with areas of grassland and savanna. During the long dry season, many trees lose their leaves, and the predominantly annual grasses die.

The Sahel was formerly home to large populations of grazing mammals, including the Scimitar-horned Oryx, Dama Gazelle, Dorcas Gazelle and Red-fronted Gazelle, and Bubal Hartebeest, along with large predators like the African Wild Dog, Cheetah, and Lion. The larger species have been greatly reduced in number by over-hunting and competition with livestock, and several species are vulnerable (Dorcas Gazelle and Red-fronted Gazelle), endangered (Dama Gazelle, African Wild Dog, cheetah, lion), or extinct (the Scimitar-horned Oryx is probably extinct in the wild, and the Bubal Hartebeest is extinct).

The seasonal wetlands of the Sahel are important for migratory birds moving within Africa and on the African-Eurasian flyways.[1]

Early agriculture

The first instances of domestication of plants for agricultural purposes in Africa occurred in the Sahel region circa 5000 B.C.E., when sorghum and African Rice began to be cultivated. Around this time, and in the same region, the small Guineafowl were domesticated.

Around 4000 B.C.E. the climate of the Sahara and the Sahel started to become drier at an exceedingly fast pace. This climate change caused lakes and rivers to shrink rather significantly and caused increasing desertification. This, in turn, decreased the amount of land conducive to settlements and helped to cause migrations of farming communities to the more humid climate of West Africa.[2]

Sahelian kingdoms

The Sahelian kingdoms were a series of empires, based in the Sahel, which had many similarities. The wealth of the states came from controlling the Trans-Saharan trade routes across the desert. Their power came from having large pack animals like camels and horses that were fast enough to keep a large empire under central control and were also useful in battle. All of these empires were also quite decentralized with member cities having a great deal of autonomy. The first large Sahelian kingdoms emerged after 750, and supported several large trading cities in the Niger Bend region, including Timbuktu, Gao, and Djenné.

The Sahel states were limited from expanding south into the forest zone of the Ashanti and Yoruba as mounted warriors were all but useless in the forests and the horses and camels could not survive the heat and diseases of the region.

List of the Sahel Kingdoms

- The first major state to rise in this region was the Kingdom of Ghana. Centered in what is today Senegal and Mauritania, it was the first to benefit from the introduction of pack animals by Arab traders. Ghana dominated the region between about 750 and 1078. Smaller states in the region at this time included Takrur to the west, the Malinke kingdom of Mali to the south, and the Songhai centered around Gao to the east.

- When Ghana collapsed in the face of invasion from the Almoravids, a series of brief kingdoms followed, notably that of the Sosso; after 1235, the Mali Empire rose to dominate the region. Located on the Niger River to the west of Ghana in what is today Niger and Mali, it reached its peak in the 1350s, but had lost control of a number of vassal states by 1400.

- The most powerful of these states was the Songhai Empire, which expanded rapidly beginning with king Sonni Ali in the 1460s. By 1500, it had risen to stretch from Cameroon to the Maghreb, the largest state in African history. It too was quite short-lived and collapsed in 1591 as a result of Moroccan musketry.

- Far to the east, on Lake Chad, the state of Kanem-Bornu, founded as Kanem in the 800s, now rose to greater preeminence in the central Sahel region. To their west, the loosely united Hausa city-states became dominant. These two states coexisted uneasily, but were quite stable.

- In 1810 the Fulani Empire rose and conquered the Hausa, creating a more centralized state. It and Kanem-Bornu would continue to exist until the arrival of Europeans, when both states would fall and the region would be divided between France and Great Britain.

Transhumance

Traditionally, most of the people in the Sahel have been semi-nomads, farming and raising livestock in a system of transhumance, which is probably the most sustainable way of utilizing the Sahel. The difference between the dry north with higher levels of soil-nutrients and the wetter south is utilized so that the herds graze on high quality feed in the north during the wet season, and trek several hundred kilometers down to the south, to graze on more abundant, but less nutritious feed during the dry period. Increased permanent settlement and pastoralism in fertile areas has been the source of conflicts with traditional nomadic herders.

Twentieth century droughts

There was a major drought in the Sahel in 1914, caused by annual rains far below average, that caused a large-scale famine.

The 1960s saw a large increase in rainfall in the region, making the northern, drier, region more accessible. There was a push, supported by governments, for people to move northward, and as the long drought-period from the late 1960s to early 1980s kicked in, the grazing quickly became unsustainable, and large-scale denuding of the terrain followed.

Like the drought in 1914, this led to a large-scale famine that killed a million people and afflicted more than 50 million. The economies, agriculture, livestock, and human populations of much of Mauritania, Mali, Chad, Niger and Burkina Faso (known as Upper Volta during the time of the drought) were severely impacted.

Unlike during the 1914 drought, this famine was somewhat tempered by international visibility and an outpouring of aid. In 1973, The United Nations Sahelian Office (UNSO) was created to address the severe effects of recurrent droughts in the Sahel. In the 1990s, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) was adopted and UNSO became the United Nations Development Programme's Office to Combat Desertification and Drought, as its scope broadened to a global level rather than only a focus on Africa.[3]

This catastrophic drought also led to the founding of the International Fund for Agricultural Development in 1977, one of the major outcomes of the 1974 World Food Conference. The Conference was organized in response to the food crises of the early 1970s brought on by the Sahelian drought.[4]

Looking to the future

The people of the Sahel have been both victims and abusers of the environment. Destructive measures have been implemented in the region, such as the clearing of large areas of the green belt of all vegetation in order to make way for annual crops. A system such as increasing the population of perennials in the agricultural zone would stabilize the land. A symbiotic relationship would form in which the land would be the beneficiary of man's presence and man would benefit via the results of positive control of the natural environment.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 World Wildlife Fund, 2001, Sahelian Acacia savanna (AT0713). Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- ↑ Patrick K. O'Brien, Oxford Atlas of World History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

- ↑ United Nations Development Programme, Our History. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- ↑ International Fund for Agricultural Development, About IFAD. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Eden Foundation. Desertification—a threat to the Sahel. August 1994. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- National Geographic Society. Sahelian Acacia savanna (AT0713). Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- O'Brien, Patrick K. Oxford Atlas of World History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0199746538

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Jean-Paul Azam, Christian Morrisson, Sophie Chauvin, and Sandrine Rospabé. Conflict and Growth in Africa. Vol. 1, The Sahel. Development Centre studies. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 1999. ISBN 9264171010.

- Salgado, Sebastião. Sahel: The End of the Road. Series in contemporary photography, 3. Berkeley, CA: University of California, 2004. ISBN 9780520241701.

- Skreslet, Paula Youngman. Northern Africa a Guide to Reference and Information Sources. Reference sources in the social sciences series. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited, 2000. ISBN 9780313009426.

- World Wildlife Fund. Sahelian Acacia savanna (AT0713). 2001. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.