Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste (c. 1175 - October 9, 1253), an English statesman, scholastic philosopher, theologian, and bishop of Lincoln, is well-known for his outspoken criticism of the Roman Catholic Church’s involvement in secular politics and of the government’s involvement in church affairs, and for the ecclesiastical reforms which he carried out in England. He was also considered the first mathematician and physicist of his age, and laid the groundwork for modern scientific method.

Grosseteste was the first of the Scholastics to fully understand Aristotle's vision of the dual path of scientific reasoning: Generalizing from particular observations into a universal law, and then back again from universal laws to prediction of particulars. He also developed the idea of the subordination of the sciences, showing that knowledge of certain scientific fields was based on the prior understanding of other fields of natural science. He identified mathematics as the “first science,” since every natural science depended on mathematics. His scientific work especially influenced Roger Bacon. Grosseteste introduced Latin translations of Greek and Arabic philosophical and scientific writings to European Christian scholars, and wrote a number of commentaries on Aristotle.

Biography

Robert Grosseteste was born around 1175, of humble parents at Stradbroke in Suffolk, England. Little is known about his origins; Grosseteste was probably a family name. Grosseteste received his education at Oxford, where he became proficient in law, medicine, and the natural sciences. Giraldus Cambrensis, whose acquaintance he had made, recommended him, before 1199, to William de Vere, bishop of Hereford. Grosseteste aspired to a post in the bishop's household, but when this patron died, he took up the study of theology.

Local tradition, his intimacy with a number of French ecclesiastics and with the details of the Paris curriculum, and his knowledge of French suggest that he studied and taught theology in Paris. One of the most popular of the many writings attributed to him was a French religious romance, the Chasteau d'Amour. He finally settled in Oxford as a teacher, and as head of Greyfriars, Oxford.

His next important appointment was the chancellorship of the university. He gained considerable distinction as a lecturer, and was the first rector of the school which the Franciscans established in Oxford about 1224. Grosseteste's learning is highly praised by Roger Bacon, who was a severe critic. According to Bacon, Grosseteste knew little Greek or Hebrew and paid slight attention to the works of Aristotle, but was preeminent among his contemporaries for his knowledge of the natural sciences. In Opus Tertium Bacon says: "No one really knew the sciences, except the Lord Robert, Bishop of Lincoln, by reason of his length of life and experience, as well as of his studiousness and zeal. He knew mathematics and perspective, and there was nothing which he was unable to know, and at the same time he was sufficiently acquainted with languages to be able to understand the saints and the philosophers and the wise men of antiquity." Between 1214 and 1231, Grosseteste held in succession the archdeaconries of Chester, Northampton and Leicester. He simultaneously held several livings and a prebend at Lincoln, but an illness in 1232, led to his resigning all his preferments except the Lincoln prebend, motivated by a deepened religious fervor and by a real love of poverty. In 1235, he was freely elected to the Bishopric of Lincoln, the most populous diocese in England, and he was consecrated in the abbey church of Reading, in June of the following year, by St. Edmund Rich, Archbishop of Canterbury.

He undertook without delay the reformation of morals and clerical discipline throughout his vast diocese. This effort brought him into conflict with more than one privileged group, and in particular with his own chapter, who vigorously disputed his claim to exercise the right of visitation over their community and claimed exemption for themselves and their churches. The dispute raged hotly from 1239 to 1245, conducted on both sides with unseemly violence, and even those who supported Grosseteste warned him against being overzealous. Grosseteste discussed the whole question of episcopal authority in a long letter (Letter cxxvii, Rob. Grosseteste Epistolæ, Rolls Series, 1861) to the dean and chapter, and was forced to suspend and ultimately to deprive the dean, while the canons refused to attend in the chapter house. There were appeals to the pope and counter appeals and several attempts at arbitration. Eventually, Innocent IV settled the question, in the bishop's favor, at Lyons in 1245.

In ecclesiastical politics, Grosseteste followed the ideas of Becket. On several occasions he demanded that the legal courts rule according to Christian principles which went beyond the jurisdiction of secular law. King Henry III rebuked him twice, and King Edward I finally settled the question of principle in favor of the secular government. Grosseteste was also strongly committed to enforcing the hierarchy of the church. He upheld the prerogative of the bishops to overrule decisions made by the chapters of religious orders, and gave the commands of the Holy See priority over the orders of the King. When Rome attempted to curtail the liberties of the church in England, however, he defended the autonomy of the national church. In 1238, he demanded that the King should release certain Oxford scholars who had assaulted the papal legate Otho.

Grosseteste was highly critical of the Roman Catholic Church’s involvement in secular politics, and of the financial demands placed on the church in England. His correspondence shows that, at least up to the year 1247, he submitted patiently to papal encroachments, contenting himself with the a special papal privilege which protected his own diocese from alien clerks.

After the retirement of Archbishop Edmund Rich, Grosseteste became the spokesman of the clerical estate in the Great Council of England. In 1244, he sat on a committee which was empaneled to consider a demand from the king for a financial subsidy from the church. The committee rejected the demand, and Grosseteste foiled an attempt by the king to create division between the clergy and the nobility. "It is written," the bishop said, "that united we stand and divided we fall."

It soon became clear that the king and pope were in alliance to crush the independence of the English clergy; and from 1250, onwards Grosseteste openly criticized the new financial expedients to which Innocent IV had been driven by his desperate conflict with the Empire. During a visit to Pope Innocent IV in 1250, the bishop laid before the pope and cardinals a written memorial in which he ascribed all the evils of the Church to the malignant influence of the Curia. It produced no effect, although the cardinals felt that Grosseteste was too influential to be punished for his audacity.

Discouraged by his failure, Grosseteste thought of resigning, but in the end decided to continue the unequal struggle. In 1251, he protested against a papal mandate enjoining the English clergy to pay Henry III one-tenth of their revenues for a crusade; and called attention to the fact that, under the system of provisions, a sum of 70,000 marks was annually drawn from England by the representatives of the church in Rome. In 1253, when he was commanded to provide a position in his own diocese for a nephew of the pope, he wrote a letter of expostulation and refusal, not to the pope himself but to the commissioner, Master Innocent, through whom he received the mandate. He argued, as an ecclesiastical reformer, that the papacy could command obedience only so far as its commands were consonant with the teaching of Christ and the apostles. Another letter addressed "to the nobles of England, the citizens of London, and the community of the whole realm," in which Grosseteste is represented as denouncing in unmeasured terms papal finance in all its branches, is of questionable authorship.

One of Grosseteste’s most intimate friends was the Franciscan teacher, Adam Marsh, through whom he came into close relations with Simon de Montfort. From Marsh's letters it appears that de Montfort had studied a political tract by Grosseteste on the difference between a monarchy and a tyranny; and that he embraced with enthusiasm the bishop's projects of ecclesiastical reform. Their alliance began as early as 1239, when Grosseteste exerted himself to bring about a reconciliation between the king and Montfort, and some scholars believe that Grosseteste influenced his political ideas. Grosseteste realized that the misrule of Henry III and his unprincipled compact with the papacy largely accounted for the degeneracy of the English hierarchy and the laxity of ecclesiastical discipline.

Grosseteste died on October 9, 1253, between the age of seventy and eighty.

Bishop Grosseteste College, a stone's throw away from Lincoln Cathedral, is named after Robert Grossesteste. The University College provides Initial Teacher Training and academic degrees at all levels.

Thought and works

Modern scholars have tended to exaggerate Grosseteste’s political and ecclesiastical career, and to neglect his performance as a scientist and scholar. When he became a bishop, however, he was already advanced in age with a firmly established reputation as an academic. As an ecclesiastical statesman he showed the same fiery zeal and versatility as in his academic career. His contemporaries, including Matthew Paris and Roger Bacon, while admitting the excellence of his intentions as a statesman, commented on his defects of temper and discretion. They saw Grosseteste as the pioneer of a literary and scientific movement, the first mathematician and physicist of his age. He anticipated, in these fields of thought, some of the striking ideas which Roger Bacon subsequently developed and made popular.

Works

Grosseteste wrote a number of early works in Latin and French while he was a clerk, including Chasteau d'amour, an allegorical poem on the creation of the world and Christian redemption, as well as several other poems and texts on household management and courtly etiquette. He also wrote a number of theological works including the influential Hexaëmeron in the 1230s. In contrast to the Aristotelian influence then prevailing in the University of Paris, Grosseteste represented an Augustinian tradition influenced by Platonic ideas. He placed the concept of light at the center of his metaphysics, and of his epistemology, giving an account of human understanding in terms of natural, and ultimately divine, illumination.

However, Grosseteste is best known as an original thinker for his work concerning what would today be called science, or the scientific method.

From about 1220 to 1235, he wrote a host of scientific treatises including:

- De sphera. An introductory text on astronomy.

- De luce. On the "metaphysics of light."

- De accessione et recessione maris. On tides and tidal movements.

- De lineis, angulis et figuris. Mathematical reasoning in the natural sciences.

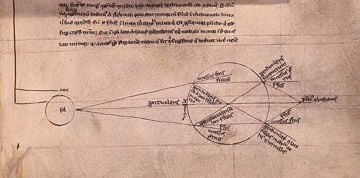

- De iride. On the rainbow.

Grosseteste introduced Latin translations of Greek and Arabic philosophical and scientific writings into the world of European Christendom. He also wrote a number of commentaries on Aristotle, including the first in the West on Posterior Analytics, and one on Aristotle's Physics.

Science

In his works of 1220-1235, in particular the Aristotelian commentaries, Grosseteste laid out the framework for the proper methods of science. Although Grosseteste did not always follow his own advice during his investigations, his work is seen as instrumental in the history of the development of the Western scientific tradition.

Grosseteste was the first of the Scholastics to fully understand Aristotle's vision of the dual path of scientific reasoning: Generalizing from particular observations into a universal law, and then back again from universal laws to prediction of particulars. Grosseteste called this "resolution and composition." For example, by looking at the particulars of the moon, it is possible to arrive at universal laws about nature. Conversely, once these universal laws are understood, it is possible to make predictions and observations about other objects besides the moon. Further, Grosseteste said that both paths should be verified through experimentation in order to affirm the principles. These ideas established a tradition that carried forward to Padua and Galileo Galilei in the seventeenth century.

As important as "resolution and composition" would become to the future of Western scientific tradition, more important to his own time was his idea of the subordination of the sciences. For example, when looking at geometry and optics, optics is subordinate to geometry because optics depends on geometry. Grosseteste concluded that mathematics was the highest of all sciences, and the basis for all others, since every natural science ultimately depended on mathematics. He supported this conclusion by looking at light, which he believed to be the "first form" of all things; it was the source of all generation and motion (corresponding roughly to the “biology” and “physics” of today). Since light could be reduced to lines and points, and thus fully explained in the realm of mathematics, mathematics was the highest order of the sciences.

Gresseteste's work in optics was also relevant and would be continued by his most famous student, Roger Bacon. In De Iride Grosseteste writes:

This part of optics, when well understood, shows us how we may make things a very long distance off appear as if placed very close, and large near things appear very small, and how we may make small things placed at a distance appear any size we want, so that it may be possible for us to read the smallest letters at incredible distances, or to count sand, or seed, or any sort or minute objects.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Crombie, A. C. Robert Grosseteste and the Origins of Experimental Science. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961.

- Marrone, Steven P. William of Auvergne and Robert Grosseteste: New Ideas of Truth in the Early Thirteenth Century. Princeton Univ Pr, 1983. ISBN 0691053839

- McEvoy, James. Robert Grosseteste (Great Medieval Thinkers). Oxford University Press, USA, 2000. ISBN 0195114493

- Riedl, Clare. On Light: Robert Grosseteste. Marquette University Press, 1983. ISBN 0874622018

- Southern, R. W. Robert Grosseteste: The Growth of an English Mind in Medieval Europe. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986. ISBN 0198203101

External links

All links retrieved December 15, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.