Panchatantra

The Panchatantra[1][2] (also spelled Pañcatantra, Sanskrit: पञ्चतन्त्र "Five Principles") or Kalīla o Damna (Persian: کلیله و دمنه) or Anvar-i-Suhayli[3][4] or The Lights of Canopus (in Persian)[5] or Kalilag and Damnag (in Syriac)[6] or Kalila and Dimna (also Kalilah and Dimnah, Arabic: كليلة و دمنة Kalila wa Dimna)[7] or The Fables of Bidpai/Pilpai (in various European languages)[8][9] or The Morall Philosophie of Doni (English, 1570) was originally a canonical collection of Sanskrit (Hindu) as well as Pali (Buddhist) animal fables in verse and prose. The original Sanskrit text, now long lost, and which some scholars believe was composed in the third century B.C.E.,[10] is attributed to Vishnu Sarma (third century B.C.E.). However, based as it is on older oral traditions, its antecedents among storytellers probably hark back to the origins of language and the subcontinent's earliest social groupings of hunting and fishing folk gathered around campfires.[11]

Origins and Purpose

The Panchatantra is an ancient synthetic text that continues its process of cross-border mutation and adaptation as modern writers and publishers struggle to fathom, simplify and re-brand its complex origins.[12] [13]

It illustrates, for the benefit of princes who may succeed to a throne, the central Hindu principles of Raja niti (political science) through an inter-woven series of colorful animal tales. These operate like a succession of Russian stacking dolls, one narrative opening within another, sometimes three or four deep, and then unexpectedly snapping shut in irregular rhythms to sustain attention (like a story within a story).[14][15]

The five principles illustrated are:

- Mitra Bhedha (The Loss of Friends)

- Mitra Laabha (Gaining Friends)

- Suhrudbheda (Causing Dissension Between Friends)

- Vigraha (Separation)

- Sandhi (Union)

History of Cross-Cultural Transmission

The Panchatantra approximated its current literary form within the fourth—sixth centuries C.E. According to Hindu tradition, the Panchatantra was written around 200 B.C.E. by Pandit Vishnu Sarma, a sage; however, no Sanskrit versions of the text before 1000 C.E. have survived.[16] One of the most influential Sanskrit contributions to world literature, it was exported (probably both in oral and literary formats) north to Tibet and China and east to South East Asia by Buddhist Monks on pilgrimage.[17]

According to the Shahnameh (The Book of the Kings, Persia's late tenth century national epic by Ferdowsi)[18] the Panchatantra also migrated westwards, during the Sassanid reign of Nushirvan around 570 C.E. when his famous physician Borzuy translated it from Sanskrit into the middle Persian language of Pahlavi, transliterated for Europeans as Kalile va Demne (a reference to the names of two central characters in the book).[19]

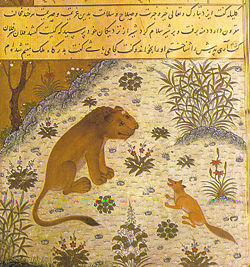

Karataka ('Horribly Howling') and Damanaka ('Victor') are the Sanskrit names of two jackals in the first section of the Panchatantra. They are retainers to a lion king and their lively adventures as well as the stories they and other characters tell one another make up roughly 45 percent of the book's length. By the time the Sanskrit version had migrated several hundred years through Pahlavi into Arabic, the two jackals' names had changed into Kalila and Dimna, and—probably because of a combination of first-mover advantage, Dimna's charming villainy and that dominant 45 percent bulk—their single part/section/chapter had become the generic, classical name for the whole book. It is possible, too, that the Sanskrit word 'Panchatantra' as a Hindu concept could find no easy equivalent in Zoroastrian Pahlavi.

From Borzuy's Pahlavi translation titled, Kalile va Demne, the book was translated into Syriac and Arabic—the latter by Ibn al-Muqaffa around 750 C.E. [20] under the Arabic title, Kalīla wa Dimma.[21]

Scholars aver that the second section of Ibn al-Muqaffa's translation, illustrating the Sanskrit principle of Mitra Laabha (Gaining Friends), became the unifying basis for the Brethren of Purity—the anonymous ninth century C.E. Arab encyclopedists whose prodigious literary effort, Encyclopedia of the Brethren of Sincerity, codified Indian, Persian and Greek knowledge.[22]

Philip K. Hitti in his History of the Arabs, proposes that:

"The appellation is presumably taken from the story of the ringdove in Kalilah wa-Dimnah in which it is related that a group of animals by acting as faithful friends (ikhwan al-safa) to one another escaped the snares of the hunter. The story concerns a ring-dove and its companions who have become entangled in the net of a hunter seeking birds. Together, they left themselves and the ensnaring net to a nearby rat, who is gracious enough to gnaw the birds free of the net; impressed by the rat's altruistic deed, a crow becomes the rat's friend. Soon a tortoise and gazelle also join the company of animals. After some time, the gazelle is trapped by another net; with the aid of the others and the good rat, the gazelle is soon freed, but the tortoise fails to leave swiftly enough and is himself captured by the hunter. In the final turn of events, the gazelle repays the tortoise by serving as a decoy and distracting the hunter while the rat and the others free the tortoise. After this, the animals are designated as the Ikwhan al-Safa.[23]

This story is mentioned as an exemplum when the Brethren speak of mutual aid in one rasa'il (treatise), a crucial part of their system of ethics that has been summarized thus:

"And their virtues, equally, are not the virtues of Islam, not so much righteousness and the due quittance of obligations, as mildness and gentleness towards all men, forgiveness, long-suffering, and compassion, the yielding up of self for others' sake. In this Brotherhood, self is forgotten; all act by the help of each, all rely upon each for succour and advice, and if a Brother sees it will be good for another that he should sacrifice his life for him, he willingly gives it. No place is found in the Brotherhood for the vices of the outside world; envy, hatred, pride, avarice, hypocrisy, and deceit, do not fit into their scheme,—they only hinder the worship of truth."[24]

After the Muslim invasion of Persia (Iran) Ibn al-Muqaffa's 750 C.E. Arabic version (by now two languages removed from its pre-Islamic Sanskrit original) emerges as the pivotal surviving text that enriches world literature.[25]

From Arabic it was transmitted in 1080 C.E. to Greece, and in 1252 into Spain (old Castillian, Calyla e Dymna) and thence to the rest of Europe. However, it was the ca. 1250 Hebrew translation attributed to Rabbi Joel that became the source (via a subsequent Latin version done by one John of Capua around 1270 C.E., Directorium Humanae Vitae, or "Directory of Human Life") of most European versions. Furthermore, in 1121, a complete 'modern' Persian translation from Ibn al-Muqaffa's version flows from the pen of Abu'l Ma'ali Nasr Allah Munshi.

Content

Each distinct part of the Panchatantra contains "at least one story, and usually more, which are 'emboxed' in the main story, called the 'frame-story'. Sometimes there is a double emboxment; another story is inserted in an 'emboxed' story. Moreover, the [whole] work begins with a brief introduction, which as in a frame all five … [parts] are regarded as 'emboxed'." Vishnu Sarma's idea was that humans can assimilate more about their own habitually unflattering behavior if it is disguised in terms of entertainingly configured stories about supposedly less illustrious beasts than themselves.[26]

Professor Edgerton challenges the assumption that animal fables function mainly as adjuncts to religious dogma, acting as indoctrination devices to condition the moral behavior of small children and obedient adults. He suggests that in the Panchatantra, "Vishnu Sarma undertakes to instruct three dull and ignorant princes in the principles of polity, by means of stories …. [This is] a textbook of artha, 'worldly wisdom', or niti, polity, which the Hindus regard as one of the three objects of human desire, the other being dharma, 'religion or morally proper conduct' and kama 'love' …. The so-called 'morals' of the stories have no bearing on morality; they are unmoral, and often immoral. They glorify shrewdness, practical wisdom, in the affairs of life, and especially of politics, of government."

The text's political realism explains why the original Sanskrit villain jackal, the decidedly jealous, sneaky and evil vizier-like Damanaka ('Victor') is his frame-story's winner, and not his noble and good brother Karataka who is presumably left 'Horribly Howling' at the vile injustice of Part One's final murderous events. In fact, in its steady migration westward the persistent theme of evil-triumphant in Kalila and Dimna, Part One frequently outraged Jewish, Christian and Muslim religious leaders—so much so, indeed, that ibn al-Muqaffa carefully inserts (no doubt hoping to pacify the powerful religious zealots of his own turbulent times) an entire extra chapter at the end of Part One of his Arabic masterpiece, putting Dimna in jail, on trial and eventually to death.

Needless to say there is no vestige of such dogmatic moralizing in the collations that remain to us of the pre-Islamic original—the Panchatantra.

Literary Impact

The Panchatantra has been translated into numerous languages around the world with their own distinct versions of the text. Given the work's allegorical nature and political intent, it was subject to diverse interpretations in the course of its cultural and linguistic transmission. Consequently, the various extant versions of the Panchatantra in existance today not only contain hermeneutical challenges for literary critics but also provide interesting case studies for cross-cultural and cross-linguistic textual syncretistism.

Literary critics have noted a strong similarity between the Panchatantra and Aesop's fables.[27] Similar animal fables are found in most cultures of the world, although some folklorists view India as the prime source.

Professor James Kritzeck, in his 1964 Anthology of Islamic Literature, confronts the book's matrix of conundrums:

"On the surface of the matter it may seem strange that the oldest work of Arabic prose which is regarded as a model of style is a translation from the Pahlavi (Middle Persian) of the Sanskrit work Panchatantra, or The Fables of Bidpai, by Ruzbih, a convert from Zoroastrianism, who took the name Abdullah ibn al-Muqaffa. It is not quite so strange, however, when one recalls that the Arabs had much preferred the poetic art and were at first suspicious of and untrained to appreciate, let alone imitate, current higher forms of prose literature in the lands they occupied.

Leaving aside the great skill of its translation (which was to serve as the basis for later translations into some forty languages), the work itself is far from primitive, having benefited already at that time 750 C.E. from a lengthy history of stylistic revision. Kalilah and Dimnah is in fact the patriarchal form of the Indic fable in which animals behave as humans—as distinct from the Aesopic fable in which they behave as animals. Its philosophical heroes through the initial interconnected episodes illustrating The Loss of Friends, the first Hindu principle of polity are the two jackals, Kalilah and Dimnah."[28]

Doris Lessing says at the start of her introduction to Ramsay Wood's 1980 "retelling" of only the first two (Mitra Bhedha—The Loss of Friends & Mitra Laabha—Gaining Friends) of the five Panchatantra principles,[29] is that "…it is safe to say that most people in the West these days will not have heard of it, while they will certainly at the very least have heard of the Upanishads and the Vedas. Until comparatively recently, it was the other way around. Anyone with any claim to a literary education knew that the Fables of Bidpai or the Tales of Kalila and Dimna—these being the most commonly used titles with us—was a great Eastern classic. There were at least 20 English translations in the hundred years before 1888. Pondering on these facts leads to reflection on the fate of books, as chancy and unpredictable as that of people or nations."

Notes

- ↑ Panachatantra translated from the Sanskrit by Arthur W. Ryder, (Bombay: Jaico Publishing House, 1949) (from Ryder's esteemed original 1924 translation, also from the 1199 C.E. North Western Family text.)

- ↑ The Panachatantra, The Book of India's Folk Wisdom, translated from the Sanskrit by Patrick Olivelle, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1997), [1] (This translation is from the so-called Southern Family Sanskrit text, as is Franklin Edgerton's equally esteemed 1924 version [see Note 21 below].)

- ↑ The Anvari Suhaili; or the Lights of Canopus Being the Persian version of the Fables of Pilpay; or the Book Kalílah and Damnah rendered into Persian by Husain Vá'iz U'L-Káshifí, translated by Edward B. Eastwick, (Stephen Austin, Bookseller to the East-India College, Hertford, 1854).

- ↑ The Anwar-I-Suhaili Or Lights of Canopus Commonly Known As Kalilah And Damnah Being An Adaptation By Mulla Husain Bin Ali Waiz-Al-Kashifi of The Fables of Bidapai, translated by Arthur N. Wollaston, (London: W. H. Allen, 1877)

- ↑ The Lights of Canopus, described by J. V. S Wilkinson, (London: The Studio Limited, 1930)

- ↑ Ion Keith-Falconer. Kalilah and Dimnah or The Fables of Bidpai.(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1885), reprinted (Amsterdam: Philo Press, 1970)

- ↑ Rev. Wyndham Knatchbull. Kalila and Dimna, or The Fables of Bidpai. (Oxford: 1819) (translated from Silvestre de Stacy's laborious 1816 collation of different Arabic manuscripts)

- ↑ The earliest English version of the Fables of Bidpai by Joseph Jacobs, (London: 1888) (edited and induced from The Morall Philosophie of Doni by Sir Thomas North, 1570)

- ↑ The Fables of Pilpay, facsimile reprint of the 1775 edition, (London: Dwarf Publishers, 1987)

- ↑ The earliest English version of the Fables of Bidpai by Joseph Jacobs, (London: 1888), Introduction, xv: "The latest date at which the stories were thus connected is fixed by the fact that some of them have been sculpted round the sacred Buddhist shrines of Sanchi, Amaravati, and the Bharhut, in the last case with the titles of the Jatakas inscribed above them. These have been dated by Indian archaeologists as before 200 B.C.E., and Mr Rhys-Davids produces evidence which would place the stories as early as 400 B.C.E. Between 400 B.C.E. and 200 B.C.E., many of our tales were put together in a frame formed of the life and experience of the Buddha."

- ↑ Doris Lessing. Problems, Myths and Stories. (London: Institute for Cultural Research Monograph Series No. 36. 1999), 13, quote: "… when we in our time talk of stories, tales, we often forget that for most of human history, thousands of years—tales were told or sung. Reading came much later, is comparatively recent, and changed not only our way of receiving tales, but also the actual machinery of our minds. The print revolution lost us our memories—or partly. Before people kept information in their heads. One may even now meet an old man or woman, illiterate, who reminds us what we once were—what everybody was like. They remember everything, what was said by whom, when and why: dates, places, addresses, history. They don't need to refer to reference books. This faculty disappeared with print."

- ↑ Kalila and Dimna, Selected fables of Bidpai, retold by Ramsay Wood (with an Introduction by Doris Lessing), Illustrated by Margaret Kilrenny, (New York: Alfred A Knopf, (1980), 1983. ISBN 0586084096.

- ↑ Denys Johnson-Davies. Animal Tales of the Arab World, illustrated by Eda S. Ghali. (Cairo: Hoopoe Books, 1995. ISBN 9775325390)

- ↑ For an extravagant and hypnotic cinematic employment of this technique, reconstructing the ancient psychological context of storytelling and oral transmission, watch Wojciech Jerzy Has's unusual and influential 1965 Polish film The Saragossa Manuscript, restored and released in video in 2000 by Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola in dedication to Jerry Garcia. [2][3] brightlightsfilm.com. Retrieved April 19, 2009.

- ↑ Also, in a more directly Middle Eastern vein, try the video or DVD of Pier Paolo Pasolini's luxuriant Arabian Nights (1974),[4] which the Arab scholar Robert Irwin [see note 25 below] praised as " wonderful… the only version made for adults."

- ↑ The Panchatantra, translated in 1924 from the Sanskrit by Franklin Edgerton, (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1965), 9, which was reconstructed from a minute study of all texts which seem "to provide useful evidence on the lost Sanskrit text to which, it must be assumed, they all go back."

- ↑ For a sense of how at least some of these monks must have travelled in ancient time, see Tarquin Hall's review of Shadow of the Silk Road by Colin Thubron, (London: Chatto & Windus, 2006), at [5]. New Statesman Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ↑ The Shāh Nãma, The Epic of the Kings, translated by Reuben Levy, revised by Amin Banani, (London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1985), Chapter XXXI (iii) "How Borzuy brought the Kalila of Demna from Hindustan," 330-334.

- ↑ Abdolhossein Zarrinkoub. Naqde adabi. (Tehran: 1959), 374-379. (See Contents 1.1 Pre-Islamic Iranian literature)

- ↑ The Fables of Kalila and Dimnah, translated from the Arabic by Saleh Sa'adeh Jallad. (London: Melisende, 2002. ISBN 1901764141).

- ↑ Ian Richard Netton. Muslim Neoplatonist: An Introduction to the Thought of the Brethren of Purity. Edinburgh University Press, 1991. ISBN 0748602518)

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Philip K. Hitti. History of the Arabs, Revised, 10th Ed. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. ISBN 0333631420).

- ↑ Stanley Lane-Poole. Studies in a Mosque. (Beirut: 1883), 199; reprinted, (Beirut: Khayat Book & Publishing Company, 1966), 189.

- ↑ See 14 illuminating commentaries about or relating to Kalila wa Dimna under the entry for Ibn al-Muqqaffa in the INDEX of The Penguin Anthology of Classical Arabic Literature by Robert Irwin, (London: Penquin Books, 2006)

- ↑ Edgerton, Franklin. The Panchatantra, translated in 1924 from the Sanskrit by Franklin Edgerton, (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1965)

- ↑ Compare, for example, 'Ass in Panther's Skin' with 'Ass without Heart and Ears'. cf. The Panchatantra translated in 1924 from the Sanskrit by Franklin Edgerton, (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1965), 13.

- ↑ page 73, a Meridian Book published by New American Library, New York 1964. See also pages 69 - 72 for his vivid summary of Ibn al-Muqaffa's historical context.

- ↑ Kalila and Dimna, Selected fables of Bidpai, retold by Ramsay Wood (with an Introduction by Doris Lessing), Illustrated by Margaret Kilrenny, (London: A Paladin Book, 1982)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beck, Brenda E. F., et al. Folktales of India (Folktales of the World). University Of Chicago Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0226040837.

- Benton, Catherine. God of Desire: Tales of Kamadeva in Sanskrit Story Literature. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0791465653.

- De Blois, François. Burzoy's Voyage to India and the Origin of the Book of Kalilah wa Dimna. London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1990. ISBN 9780947593063.

- Edgerton, Franklin, translator. The Panchatantra translated in 1924 from the Sanskrit. A. S. Barnes and Company, 1965. ISBN 0527026778. (An Edition for the General Reader)

- Hertel, Johannes. The Panchatantra-Text Of Purnabhadra: And Its Relation To Texts Of Allied Recensions As Shown In Parallel Specimens. (original 1912) reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2006. ISBN 978-1428647466.

- Hitti, Philip K. History of the Arabs. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. ISBN 978-0333631416.

- Ibn al-Muqaffa, Abdallah. Kalila und Dimna. Die Fabeln des Bidpai. Manesse-Verlag, 1995. ISBN 978-3717518723.

- Johnson-Davies, Denys. Animal Tales of the Arab World, illustrated by Eda S. Ghali. Cairo: Hoopoe Books, 1995. ISBN 9775325390.

- Kalila and Dimna, Selected fables of Bidpai, retold by Ramsay Wood (with an Introduction by Doris Lessing), Illustrated by Margaret Kilrenny. New York: Alfred A Knopf, (1980), 1983. ISBN 0586084096.

- Kalila et Dimna, Fables indiennes de Bidbai, choisies et racontées par Ramsay Wood, Albin Michel, Paris 2006[6] (in French)

- Keith-Falconer, Ion. Kalilah and Dimnah or The Fables of Bidpai. (original 1885) reprinted Amsterdam: Philo Press, 1970. ISBN 9060222547.

- Kritzeck, James. Anthology of Islamic Literature from the Rise of Islam to Modern Times. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. 1964.

- Lane-Poole, Stanley. Studies in a Mosque. (Beirut: 1883), 199; reprinted, (Beirut: 1966; Kessinger Publishing, 2007. ISBN 0548101981.

- Netton, Ian Richard. Muslim Neoplatonist: An Introduction to the Thought of the Brethren of Purity. Edinburgh University Press, 1991. ISBN 0748602518.

- The Panachatantra, The Book of India's Folk Wisdom, translated from the Sanskrit by Patrick Olivelle. (Oxford World's Classics) Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, Oxford, (1997) 2002. ISBN 0192839888.

- Ryder, Arthur W. Panachatantra translated from the Sanskrit by Arthur W. Ryder. (original 1925) reprint, The University of Chicago Press, 1958.

- Sharma, Pandit V. "Panchatantra: The Complete Version" Rupa & Co, 1991. ISBN 978-8171670659.

- Sarma, Visnu. The Panachatantra, translated from the Sanskrit by Chandra Rajan, London: Penquin Books, 1993. ISBN 0140455205. (This translation is from the Jain monk Purnabhadra's 1199 C.E. so-called North Western Family Sanskrit text that blends and rearranges at least three earlier versions.)

- Sulayman Al-Bassam. Kalila wa Dimna or The Mirror for Princes by Sulayman Al-Bassam, London: Oberon Modern Plays, 2006. ISBN 1840026707.

- Thubron, Colin. Shadow of the Silk Road. London: Chatto & Windus, 2006.

- Wood, Ramsay. Kalila and Dimna, Tales for Kings and Commoners, Selected fables of Bidpai, retold by Ramsay Wood, Introduction by Doris Lessing, Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions International, 1986.

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2022.

- "Man and Serpent", An example of comparison with an Aesop's fable Source: Joseph Jacobs, The Fables of Æsop, Selected, Told Anew, and Their History Traced. (New York: Schocken Books, 1966), 12-13. First published 1894.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.