Niflheim

Niflheim ("Land of Mists") is the realm of ice and cold in Norse mythology, whose frigid environs provide a final resting place for the dishonored dead. Hel, the grim giantess whose rules over the deceased, also makes her home here. This dreary description can be fruitfully contrasted with the glorious atmosphere of camaraderie and revelry awaiting warriors in Valhalla.

In a cosmological context, Niflheim is important for two reasons: first, it provides a site for one of the world tree's roots (Yggdrasill) to be anchored; second, the icy realm is seen as one of the primordial sources of creation, as its frigid mists were thought to have combined with fiery gusts from nearby Muspellheim to congeal into the first living beings.

Niflheim in a Norse Context

As one of the major realms in the Norse cosmology, Midgard belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E.[1]

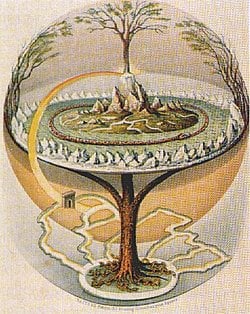

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates a universe divided into nine interrelated realms, some of which attracted considerably greater mythological attention. Of primary importance was the threefold separation of the universe into the realms of the gods (Asgard and Vanaheim, homes of the Aesir and Vanir, respectively), the realm of mortals (Midgard) and the frigid underworld (Niflheim), the realm of the dead. These three realms were supported by an enormous tree (Yggdrasil), with the realm of the gods ensconced among the upper branches, the realm of mortals approximately halfway up the tree (and surrounded by an impassable sea), and the underworld nestled among its roots. The other realms included Alfheim, world of the elves; Svartálfheim, home of the dark elves; Nidavellir, world of the dwarves (tiny men who were incomparable miners and goldsmiths), Jotunheim, world of the Jotun (giants), and Muspelheim, the hellish fire-realm that was home to Surt, a flame giant who would fight against the Aesir at Ragnarök.

Mythic Accounts

Terminological Confusion

Before venturing into an exploration of the Norse underworld (as attested to in various mythic sources), it is necessary to acknowledge that these sources are not entirely consistent in their usage of terms. More specifically, the terms Niflheim ("dark world" / "fog world") and Niflhel ("dark hell" / "fog hell") are used interchangeably in various sources, and both are occasionally used to describe the abode of Hel, the queen of the underworld and ruler over the spirits of the dead. As Lindow suggests, "the confusion between Niflheim and Nifhel is neated summed up by variation in the manuscript of Snorri's Edda. In describing the fate of the giant master builder of the wall around Asgard, two of the four main sources say that Thor bashed the giant's head and sent him to Niflheim, and the other two say that Thor sent him to Niflhel."[2] Given this uncertainty, the following analysis will examine mythic source materials related to both Niflheim and Niflhel (noting that the first term is only explicitly utilized in Snorri's Edda).

Description

The most notable characteristic of the Norse underworld was that it was a realm of dreadful, bone-chilling cold. For a hyperborean people who truly appreciated the potential hostility of untamed nature, this correlation is entirely understandable. Indeed, "one cannot help but recalling that for the Icelanders, 'cold' came from Niflheim in the North, the domain of Hel."[3] This connection is further exemplified by the localization of Hvergelmir ("hot-spring-boiler"), the fountainhead of the frigid northern rivers, within Niflheim:

It was many ages before the earth was shaped that the Mist-World [Niflheim] was made; and midmost within it lies the well that is called Hvergelmir, from which spring the rivers called Svöl ["Cool"], Gunnthrá ["Battle-pain"], Fjörm ["Rushing"], Fimbulthul ["Mighty-Speaker"], Slídr ["Dangerous"] and Hríd ["Storm"], Sylgr ["Slurp"] and Ylgr ["She-wolf"], Víd ["Wide"], Leiptr ["Flash"]; Gjöll ["Scream"] is hard by Hel-gates.[4]

This quotation, by discussing Niflheim's existence in the "many ages before the earth was shaped," clearly evidences the realm's relevance to Norse creation accounts, a correspondence that is considered in detail below.

As suggested above, Niflheim also played vital role in the mythic cosmology, as one of Yggdrasill's world-anchoring roots was located in its frost-bound soil:

The Ash is greatest of all trees and best: its limbs spread out over all the world and stand above heaven. Three roots of the tree uphold it and stand exceeding broad: one is among the Æsir; another among the Rime-Giants, in that place where aforetime was the Yawning Void; the third stands over Niflheim, and under that root is Hvergelmir, and Nídhöggr gnaws the root from below.[5]

The passage above, in addition to its relevance in detailing the relationship between Niflheim, Hvergelmir and Yggdrasill, also introduces one of the chief denizens of the frozen realm: the Nidhogg ("Malice Striker").

This creature was understood to be a chthonic dragon that had existed from the earliest epoch of mythic time, whose presence at the roots of the tree is also attested to in the Poetic Edda.[6] Intriguingly, this primordial serpent also plays a role in punishing the souls of deceased mortals, which is another major element of the Norse understanding of Niflheim. This understanding is betokened by the Völuspá, which explicitly depicts this beast's part in tormenting the dead:

- I saw there wading | through rivers wild

- Treacherous men | and murderers too,

- And workers of ill | with the wives of men;

- There Nithhogg sucked | the blood of the slain,

- And the wolf tore men; | would you know yet more?[7]

This perspective is echoed in the Prose Edda, where Hvergelmir itself is associated with these tortures:

- But it is worst in Hvergelmir:

- There the cursed snake | tears dead men's corpses.[8]

The final important dimension of Niflheim is as the realm of Hel, the queen of the underworld. This view is developed in Snorri Sturluson's account of Hel's banishment from Asgard, where he suggests that Odin cast the grim giantess "into Niflheim, and gave to her power over nine worlds, to apportion all abodes among those that were sent to her: that is, men dead of sickness or of old age."[9] In this account, the great Icelandic syncretist develops a systematic relationship between the classic Norse understandings of Hel (the posthumous destination for the souls of the deceased), Niflhel (a term that was either synonymous with Hel's realm or that represented a deeper, more unpleasant level of the underworld), and Niflheim (an all-encompassing descriptor for the entirety of the underworld).[10] Specifically, he uses the terms "Hel" and "Niflheim" as functional equivalents, and purposefully adopts the second definition of "Niflhel" (as a particularly odious realm of posthumous punishment). This view, which describes Niflhel as a ghastly "sub-basement" of Hel reserved for certain misfortunate souls, affirms Hel's ability "to apportion all abodes" to the deceased (as promised by Odin). This process is evidenced in the Prose Edda, where "evil men go to Hel and thence down to the Misty Hel [Niflhel]; and that is down in the ninth world."[11] Commenting on this, Turville-Petre suggests that, in constructing this interpretation, "Snorri seems here to be drawing on a passage in the Vafthruthnismol (str. 43), where it is said that men die from Hel into Niflhel."[12]

Specific Mythic Tales

Creation

- See also: Ymir

Though many of the earliest mythic sources in the Norse corpus (specifically those preserved in the Poetic Edda) do not contain a detailed "genesis account" of the creation of the cosmos, they do provide some intriguing hints. For instance, the Völuspá describes the world of Ymir (the primeval giant that the mortal realm was created from) as an empty and unformed place:

- Of old was the age | when Ymir lived;

- Sea nor cool waves | nor sand there were;

- Earth had not been, | nor heaven above,

- But a yawning gap, | and grass nowhere.[13]

However, this account does not speculate on the origin of Ymir himself. For this, we must turn to the Vafthruthnismol, a poem that claims to depict a contest of wits between Odin and Vafthruthnir (a preternaturally clever Jotun). Within it, Odin asks the precise question suggested above: where did the primeval giant come from? In response, Vafthruthnir spake thus:

- Down from Elivagar | did venom drop,

- And waxed till a giant it was;

- And thence arose | our giants' race,

- And thus so fierce are we found.[14]

In this way, he implies that the elemental being somehow congealed from the frosty waters of Elivagar ("storm-waves"), a term that seems to depict the confluence of rivers that emerged from Hvergelmir. While this provides a more detailed picture of the cosmic genesis, it still leaves many elements unexplored and many questions unanswered.

Such issues were not addressed until the composition of Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda, which drew upon the existing mythic sources and attempted to create a coherent system from them. In this particular case, Snorri argued that creation occurred due to the interaction between the cool, wet, frigid air of Niflheim and the hot, dry air of Muspelheim, the union of which would produce the type of gradual accretion described in the Vafthruthnismol:

Ginnungagap, which faced toward the northern quarter, became filled with heaviness, and masses of ice and rime, and from within, drizzling rain and gusts; but the southern part of the Yawning Void was lighted by those sparks and glowing masses which flew out of Múspellheim. ... Just as cold arose out of Niflheim, and all terrible things, so also all that looked toward Múspellheim became hot and glowing; but Ginnungagap was as mild as windless air, and when the breath of heat met the rime, so that it melted and dripped, life was quickened from the yeast-drops, by the power of that which sent the heat, and became a man's form.[15]

In this way, the frigid cold of Niflheim was central to the creation of the mortal realm.

Arcane Knowledge

In addition to its role in the creation of the cosmos, Niflheim (and the deceased souls entombed within it) were understood to be the resting place of great occult knowledge. Indeed, "the land of the dead, the underworld or Niflhel, is then not only the repository of all life, but also the repository of all knowledge, and hence the practice of recovering wisdom from the land of the dead."[16] Affirming this insight, Vafthruthnir, the crafty giant introduced above, admitted that his wisdom was largely gleaned from encounters with the dead:

- Vafthruthnir spake:

- "Of the runes of the gods | and the giants' race

- The truth indeed can I tell,

- (For to every world have I won;)

- To nine worlds came I, | to Niflhel beneath,

- The home where dead men dwell."[17]

This brings to mind the methods of divination utilized by Odin, such as his predilection to "awaken the dead and sit down beneath hanged men."[18] Likewise, the entire prophecy recorded in the Völuspá was drawn by the Gallows God from the unwilling lips of a deceased sibyl. Further, this same technique is detailed in Baldr's Draumr, where Odin seeks answers concerning the frightening, precognitive dreams experienced by his son Balder:

- Then Othin rode | to the eastern door,

- There, he knew well, | was the wise-woman's grave;

- Magic he spoke | and mighty charms,

- Till spell-bound she rose, | and in death she spoke...[19]

See also

- Nibelheim

- Hel

Notes

All links retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview” (27-28).

- ↑ Lindow, 241.

- ↑ Vivian Salmon, "Some Connotations of 'Cold' in Old and Middle English," Modern Language Notes 74(4) (April 1959): 314-322.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning V, Brodeur 16. Translation of river names from Lindow (189) and Orchard (136). See also "Grimnismol" (26) for an earlier discussion of Hvergelmir from the mythic corpus. The Poetic Edda, 94.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning XV, Brodeur 27.

- ↑ "Grimnismol" (35) in the Poetic Edda, 98-99: Yggdrasil's ash | great evil suffers // Far more than men do know; // The hart bites its top, | its trunk is rotting // And Nithhogg gnaws beneath.

- ↑ "Völuspá" (39) in the Poetic Edda, 17.

- ↑ Gylfaginning LII, Brodeur 82.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning XXXIV, Brodeur 42.

- ↑ Dubois takes this multi-partite understanding as evidence that "the general idea of multiple otherworlds for the dead appears to predate contact with [Christianity]" (81).

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning III, Brodeur 16.

- ↑ Turville-Petre, 271.

- ↑ Völuspá" (3) in the Poetic Edda, 4.

- ↑ "Vafthruthnismol" (31) in the Poetic Edda, 77.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning V, Brodeur 17. This cosmological schema (cold/wet meeting hot/dry and generating life) is discussed from a cross-cultural perspective in Bruce Lincoln's "The Center of the World and the Origins of Life," History of Religions 40(4) (May 2001): 311-326.

- ↑ Richard L. Auld, "The Psychological and Mythic Unity of the God, Odinn," Numen 23(2) (August 1976): 145-160.

- ↑ "Vafthruthnismol" (43) in the Poetic Edda, 80.

- ↑ Turville-Petre, 44.

- ↑ "Baldrs Draumr" (4) in the Poetic Edda, 196.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

All links retrieved June 22, 2007.

- Auld, Richard L. "The Psychological and Mythic Unity of the God, Odinn." Numen 23(2) (August 1976): 145-160.

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0812217144

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0520020448

- Grammaticus, Saxo. The Danish History (Volumes I-IX). Translated by Oliver Elton (Norroena Society, New York, 1905). Accessed online at The Online Medieval & Classical Library.

- Lincoln, Bruce. "The Center of the World and the Origins of Life." History of Religions 40(4) (May 2001): 311-326.

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0304363855

- The Poetic Edda. Translated and with notes by Henry Adams Bellows. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1936. Accessed online at Sacred-Texts.com.

- Sturluson, Snorri. The Prose Edda. Translated from the Icelandic and with an introduction by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916. Available online.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964. ISBN 0837174201

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.