Lewis Mumford

Lewis Mumford, KBE (October 19, 1895 – January 26, 1990) was an American historian, sociologist, philosopher of technology, and literary critic. Particularly noted for his study of cities and urban architecture, he had a broad career as a writer. Mumford was influenced by the work of Scottish theorist Sir Patrick Geddes and worked closely with his associate the British sociologist Victor Branford. Mumford was also a contemporary and friend of Frank Lloyd Wright, Clarence Stein, Frederic Osborn, Edmund N. Bacon, and Vannevar Bush.

Mumford regarded human relationships to be the foundation of a thriving society. He was critical of many developments in the twentieth century, warning of the destructive power of technology unharnessed by human oversight. He was vocal in his opposition to the dangers of Nazism and Fascism, and later the threat of global annihilation from the atomic bomb. Yet, he remained optimistic that humankind would survive and thrive, renewing human society through the creation of effective organic institutions that would value life over machine.

Life

Lewis Mumford was born on October 19, 1895 in Flushing, Queens, New York and was raised by his mother on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.[1] He graduated from Stuyvesant High School in 1912.

He studied at the City College of New York and The New School for Social Research. However, he became ill with tuberculosis and never finished his degree.

After that, his education was largely self-directed, using as his role model the Scots intellectual Patrick Geddes, a biologist, sociologist, geographer, and pioneering town planner. Following Geddes’ example, Mumford carried out a series of “regional surveys,” systematic walks around the neighborhoods of the New York metropolitan area during which he would sketch and take notes on the buildings and city life. Mumford's grandfather had taken him on walks all over the city every weekend, and Mumford built on this experience to carry out his surveys.[2]

In 1918 he joined the navy to serve in World War I and was assigned as a radio electrician.[3] He was discharged in 1919 and became associate editor of The Dial, an influential modernist literary journal. There he met Sophia Wittenberg, his future wife. They were married in 1921, and had two children. Their son, Geddes, was killed in action in World War II.

The Mumfords lived in Greenwich Village and Sunnyside Gardens in Queens following their marriage. After the success of Sticks and Stones, Mumford's 1924 history of American architecture, critic Joel Elias Spingarn invited him up to his Amenia estate, Troutbeck.

By 1929 the Mumfords decided to purchase a property of their own for their summers, and found a house just down the road from Troutbeck. In 1936, the family decided to settle there year-round. This was a considerable adjustment for the Mumfords, since up to that point they had been city dwellers. "There," wrote one scholar three decades later, "the rural life that previously he had only glimpsed became real to him."[4] Mumford took up gardening in earnest, and they landscaped the property, eventually adding paths that opened up vistas across the Webutuck valley to Oblong Mountain on the west. They bought a used 1932 Chevrolet, their first car. Mumford left it to his wife to drive after he nearly crashed it into the maple trees in front of the house on one attempt to learn, and swore never to get behind the wheel again.[5]

The Mumfords appreciated their neighbors' help in lending them tools and garden equipment and watching the house when they were away from it; one large family nearby was extremely helpful with the Mumford children. The experience reinforced Mumford's belief that livable city neighborhoods needed to have "something of the village" in them.[5]

They intended to stay in Amenia for only a few years, but Mumford gradually found the quiet rural environment a good place to write. It was in the downstairs study of this house that he turned out many of his later major works on the role of cities in civilization and the roots of industrialization. In the early 1940s, after his son Geddes was killed in action during World War II, Mumford recalled his son's childhood in and around the house in Green Memories.[6]

"We gradually fell in love with our shabby house as a young man might fall in love with a homely girl whose voice and smile were irresistible", Mumford later recalled. "In no sense was this the house of dreams. But over our lifetime it has slowly turned into something better, the house of our realities ... [T]his dear house has enfolded and remodeled our family character—exposing our limitations as well as our virtues."[7]

Over the rest of their lives, the Mumfords sometimes took residence elsewhere for Lewis's teaching or research positions, up to a year at a time. They always returned to what they called the "Great Good Place". Mumford's biographer Donald Miller wrote:

In the act of living in this house and making it over it became like a person to them; and like a good friend they grew more fond of it with closer and deeper acquaintance. Every patch garden and lawn, every vista and view, carried the imprint of some of the best hours of their lives.[8]

In the 1980s, when Mumford could no longer write due to his advanced age, he retreated to the house. He died there in his bed on January 26, 1990, at the age of 94. His wife Sophia died seven years later in 1997, at age 97.[3]

Work

Mumford was a journalist, critic, and academician, whose literary output consisted of over 20 books and 1,000 articles and reviews. The topics of his writings ranged from art and literature to the history of technology and urbanism. Mumford's earliest books in the field of literary criticism have had a lasting impact on contemporary American literary criticism. His first book, The Styd of Utopia, was published in 1922. In 1927 he became the editor of The American Caravan.

His 1926 book, The Golden Day, contributed to a resurgence in scholarly research on the work of 1850s American transcendentalist authors and Herman Melville: A Study of His Life and Vision (1929) effectively launched a revival in the study of the work of Herman Melville. Soon after, with the book The Brown Decades (1931), he began to establish himself as an authority in American architecture and urban life, which he interpreted in a social context.

Beginning in 1931, he worked for The New Yorker where he wrote architectural criticism and commentary on urban issues for over 30 years.

In his early writings on urban life, Mumford was optimistic about human abilities and wrote that the human race would use electricity and mass communication to build a better world for all humankind. He would later take a more pessimistic stance. His early architectural criticism also helped to bring wider public recognition to the work of Henry Hobson Richardson, Louis Sullivan, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

During the late 1930s, Mumford wrote in favor of joining the Allied Powers in World War II, believing it to be morally necessary to resist Nazism and Fascism. After the war, he turned his attention to the danger of nuclear warfare leading to global annihilation. He continued to be vocal in opposition to the destructive effects of uncontrolled technological advances, such as pollution and environmental degradation caused by industry and the automobile.[1]

Organic Humanism

In his book The Condition of Man, published in 1944, Mumford characterized his orientation toward the study of humanity as "organic humanism."[9] The term is an important one because it sets limits on human possibilities, limits that are aligned with the nature of the human body. Mumford never forgot the importance of air quality, of food availability, of the quality of water, or the comfort of spaces, because all these things had to be respected if people were to thrive. Technology and progress could never become a runaway train in his reasoning, so long as organic humanism was there to act as a brake. Indeed, Mumford considered the human brain from this perspective, characterizing it as hyperactive, a good thing in that it allowed humanity to conquer many of nature's threats, but potentially a bad thing if it were not occupied in ways that stimulated it meaningfully. Mumford's respect for human "nature," the natural characteristics of being human, provided him with a platform from which to assess technologies, and technics in general. It was from the perspective of organic humanism that Mumford eventually launched a critical assessment of Marshall McLuhan, who argued that the technology, not the natural environment, would ultimately shape the nature of humankind, a possibility that Mumford recognized, but only as a nightmare scenario.

Mumford believed that what defined humanity, what set human beings apart from other animals, was not primarily our use of tools (technology) but our use of language (symbols). He was convinced that the sharing of information and ideas amongst participants of primitive societies was completely natural to early humanity, and had been the foundation of society as it became more sophisticated and complex. He had hopes for a continuation of this process of information "pooling" in the world as humanity moved into the future.[10]

Technics

Mumford's choice of the word "technics" throughout his work was deliberate. For Mumford, technology is one part of technics. Using the broader definition of the Greek tekhne, which means not only technology but also art, skill, and dexterity, technics refers to the interplay of social milieu and technological innovation—the "wishes, habits, ideas, goals" as well as "industrial processes" of a society. As Mumford writes at the beginning of Technics and Civilization, "other civilizations reached a high degree of technical proficiency without, apparently, being profoundly influenced by the methods and aims of technics."[11]

- Polytechnics versus monotechnics

A key idea, which Mumford introduced in Technics and Civilization (1934), was that technology was twofold:

- Polytechnic, which enlists many different modes of technology, providing a complex framework to solve human problems.

- Monotechnic, which is technology only for its own sake, which oppresses humanity as it moves along its own trajectory.

Mumford criticized modern America's transportation networks as being 'monotechnic' in their reliance on cars. Automobiles become obstacles for other modes of transportation, such as walking, bicycle and public transit, because the roads they use consume so much space and are such a danger to people.

- Three epochs of civilization

Also discussed at length in Technics and Civilization is Mumford's division of human civilization into three distinct Epochs (following concepts originated by Patrick Geddes):

- Eotechnic (the Middle Ages)

- Paleotechnic (the time of the industrial revolution) and

- Neotechnic (later, present-day)

- The clock as herald of the Industrial Revolution

One of the better-known studies of Mumford is of the way the mechanical clock was developed by monks in the Middle Ages and subsequently adopted by the rest of society. He viewed this device as the key invention of the whole Industrial Revolution, contrary to the common view of the steam engine holding the prime position, writing: "The clock, not the steam-engine, is the key-machine of the modern industrial age. [...] The clock [...] is a piece of power-machinery whose 'product' is seconds and minutes [...]."[11]

- Megatechnics

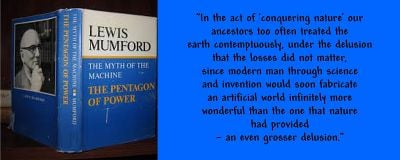

In The Myth of the Machine Vol II: The Pentagon of Power (Chapter 12) (1970),[12] Mumford criticized the modern trend of technology which emphasizes constant, unrestricted expansion, production, and replacement. He contends that these goals work against technical perfection, durability, social efficiency, and overall human satisfaction. Modern technology, which he called "megatechnics," fails to produce lasting, quality products by using devices such as consumer credit, installment buying, non-functioning and defective designs, planned obsolescence, and frequent superficial "fashion" changes.

"Without constant enticement by advertising," he writes, "production would slow down and level off to normal replacement demand. Otherwise many products could reach a plateau of efficient design which would call for only minimal changes from year to year."[12]

He uses his own refrigerator as an example, reporting that it "has been in service for nineteen years, with only a single minor repair: an admirable job. Both automatic refrigerators for daily use and deepfreeze preservation are inventions of permanent value.... [O]ne can hardly doubt that if biotechnic criteria were heeded, rather than those of market analysts and fashion experts, an equally good product might come forth from Detroit, with an equally long prospect of continued use."[12]

- Biotechnics

Mumford used the term "biotechnics" in the later sections of The Pentagon of Power.[12] The term sits well alongside his early characterization of "organic humanism," in that biotechnics represent the concrete form of technique that appeals to an organic humanist. Mumford held it possible to create technologies that functioned in an ecologically responsible manner, and he called that sort of technology "biotechnics." This was the sort of technics he believed that was needed to shake off the suicidal drive of "megatechnics."

When Mumford described biotechnics, automotive and industrial pollution had become dominant technological concerns, as was the fear of nuclear annihilation. Mumford recognized, however, that technology had even earlier produced a plethora of hazards, and that it would do so into the future. For Mumford, human hazards are rooted in a power oriented technology that does not adequately respect and accommodate the essential nature of humanity. Effectively, Mumford is stating, as others would later state explicitly, that contemporary human life, understood in its ecological sense, is out of balance, because the technical parts of its ecology (guns, bombs, cars, drugs) have spiraled out of control, driven by forces peculiar to them rather than constrained by the needs of the species that created them. He believed that biotechnics was the emerging answer; the hope that could be set against the problem of megatechnics, an answer that, he believed, was already beginning to assert itself in his time.

Mumford's critique of the city and his vision of cities that are organized around the nature of human bodies, so essential to all Mumford's work on city life and urban design, is rooted in an incipient notion of biotechnics: "livability," a notion which Mumford took from his mentor, Patrick Geddes.

Megamachines

Mumford refered to large hierarchical organizations as megamachines—a machine using humans as its components. The most recent Megamachine manifests itself, according to Mumford, in modern technocratic nuclear powers—Mumford used the examples of the Soviet and United States power complexes represented by the Kremlin and the Pentagon, respectively. The builders of the Pyramids, the Roman Empire, and the armies of the World Wars are prior examples.

He explains that meticulous attention to accounting and standardization, and elevation of military leaders to divine status are spontaneous features of megamachines throughout history. He cites such examples as the repetitive nature of Egyptian paintings which feature enlarged Pharaohs and public display of enlarged portraits of Communist leaders such as Mao Zedong and Joseph Stalin. He also cites the overwhelming prevalence of quantitative accounting records among surviving historical fragments, from ancient Egypt to Nazi Germany.

Necessary to the construction of these megamachines is an enormous bureaucracy of humans which act as "servo-units," working without ethical involvement. According to Mumford, technological improvements such as the assembly line, or instant, global, wireless, communication and remote control, can easily weaken the perennial psychological barriers to certain types of questionable actions. An example which he uses is that of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi official who conducted logistics behind the Holocaust. Mumford collectively refers to people willing to carry out placidly the extreme goals of these megamachines as "Eichmanns."

Urban civilization

The City in History won the 1962 U.S. National Book Award for Nonfiction.[13] In this influential book Mumford explored the development of urban civilizations. Harshly critical of urban sprawl, Mumford argued that the structure of modern cities is partially responsible for many social problems seen in western society. While pessimistic in tone, Mumford argued that urban planning should emphasize an organic relationship between people and their living spaces. Mumford wrote critically of urban culture believing the city to be "a product of earth ... a fact of nature ... man's method of expression."[14]

The solution according to Mumford lies in understanding the need for an organic relationship between nature and human spirituality: "The physical design of cities and their economic functions are secondary to their relationship to the natural environment and to the spiritual values of human community."[15]

Mumford used the example of the medieval city as the basis for the "ideal city," and claimed that the modern city is too close to the Roman city (the sprawling megalopolis) which ended in collapse; if the modern city carries on in the same vein, Mumford argued, then it will meet the same fate as the Roman city.

Suburbia did not escape Mumford's criticism:

In the suburb one might live and die without marring the image of an innocent world, except when some shadow of evil fell over a column in the newspaper. Thus the suburb served as an asylum for the preservation of illusion. Here domesticity could prosper, oblivious of the pervasive regimentation beyond. This was not merely a child-centered environment; it was based on a childish view of the world, in which reality was sacrificed to the pleasure principle.[16]

Legacy

Mumford received numerous awards for his work. His 1961 book, The City in History, received the National Book Award for nonf9ction.[3][13] In 1963, Mumford received the Frank Jewett Mather Award for art criticism from the College Art Association.[17] Mumford received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964, in 1975 he was made an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE), and in 1976, he was awarded the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca. In 1986, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts.[3]

Mumford's interest in the history of technology and his explanation of "polytechnics," along with his general philosophical bent, has been an important influence on a number of more recent thinkers concerned that technology serve human beings as broadly and well as possible. Some of these authors—such as Jacques Ellul, Witold Rybczynski, Richard Gregg, Amory Lovins, J. Baldwin, E. F. Schumacher, Herbert Marcuse, Murray Bookchin, Thomas Merton, Marshall McLuhan, and Colin Ward—have been intellectuals and persons directly involved with technological development and decisions about the use of technology.[18]

Mumford also had an influence on the American environmental movement, with thinkers like Barry Commoner and Bookchin being influenced by his ideas on cities, ecology and technology.[19] Ramachandra Guha noted his work contains "some of the earliest and finest thinking on bioregionalism, anti-nuclearism, biodiversity, alternate energy paths, ecological urban planning and appropriate technology."[20]

Lewis Mumford House

The Lewis Mumford House is located on Leedsville Road in the Town of Amenia, Dutchess County, New York. It is a white Federal style building dating to the 1830s. In 1999, nine years after Mumford's death in 1990, the property was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Lewis Mumford and his wife, Sophia, bought the house in the late 1920s, originally using it as a summer house. By the mid-1930s, they decided to make it their permanent residence for a few years. That period extended to more than half a century, the rest of Mumford's life. His experience of living in a rural area informed some of Mumford's thinking about cities and how they should be shaped.

After Sophia's death in 1997, the house was sold to a local carpenter who decided to restore it to its original appearance and resell it. He removed all the bookcases and the nine layers of linoleum the Mumfords had added to the kitchen floor every time one wore out. Later renovations restored the original siding and chimney.

After being listed on the National Register in 1999, the house was again put up for sale. The restorations made it more difficult to sell despite the historic provenance, since it still lacked many amenities sought by contemporary buyers of country houses. It eventually did, and is now an occupied residence again.

Works

- 1922 The Story of Utopias

- 1924 Sticks and Stones

- 1926 Architecture, Published by the American Library Association in its "Reading With a Purpose" series

- 1926 The Golden Day

- 1929 Herman Melville: A Study of His Life and Vision

- 1931 The Brown Decades: A Study of the Arts in America, 1865–1895

- "Renewal of Life" series

- 1934 Technics and Civilization

- 1938 The Culture of Cities

- 1944 The Condition of Man

- 1951 The Conduct of Life

- 1939 The City (film); Men Must Act

- 1940 Faith for Living

- 1941 The South in Architecture

- 1945 City Development

- 1946 Values for Survival

- 1952 Art and Technics

- 1954 In the Name of Sanity

- 1956 The Transformations of Man (New York: Harper and Row)

- 1961 The City in History (awarded the National Book Award)

- 1963 The Highway and the City (essay collection)

- The Myth of the Machine (two volumes)

- 1967 Technics and Human Development

- 1970 The Pentagon of Power

- 1968 The Urban Prospect (essay collection)

- 1979 My Work and Days: A Personal Chronicle

- 1982 Sketches from Life: The Autobiography of Lewis Mumford (New York: Dial Press)

- 1986 The Lewis Mumford Reader (ed. Donald L. Miller, New York: Pantheon Books)

Essays and reporting

- 1946 "Gentlemen: You are Mad!" Saturday Review of Literature March 2, 1946, 5–6.

- 1946 diatribe against nuclear weapons

- 1949 "The Sky Line: The Quick and the Dead" The New Yorker 24(46) (Jan 8, 1949): 60–65.

- Reviews the Esso Building, Rockefeller Center

- 1950 "The Sky Line: Civic Virtue" The New Yorker 25(50) (Feb 4, 1950): 58–63.

- Reviews Parke-Bernet Galleries, Madison Avenue

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Robert Wojtowicz, City As Community: The Life And Vision Of Lewis Mumford Quest 4(1) (Jan 2001).

- ↑ Lewis Mumford (1895-1990) Lewis Mumford Center. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Chronology of Mumford's Life Lewis Mumford Center. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ↑ David R. Weimer, "Anxiety in the Golden Day of Lewis Mumford" The New England Quarterly 36(2) (June 1963): 172–191.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Donald L. Miller, Lewis Mumford: A Life (NY: Grove Press, 2002, ISBN 0802139345), 378.

- ↑ Langdon Winner, "Hot Property in Leedsville: The Mumford Property Up For Sale" NetFuture 109 (2000). Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ↑ Wilfred M. McClay and Ted V. McAllister (eds), Why Place Matters: Geography, Identity, and Civic Life in Modern America (Encounter Books, 2014, ISBN 978-1594037160), 258.

- ↑ Miller, 377.

- ↑ Lewis Mumford, The Condition of Man (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1944, ASIN B0006D9C0K).

- ↑ Lewis Mumford, "Enough Energy for Life & The Next Transformation of Man" [MIT lecture transcript] CoEvolution Quarterly 1(4) (1974): 19–23.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (London: Routledge, 1934).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Lewis Mumford, The Myth of the Machine Vol II: The Pentagon of Power (Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich, 1974, ISBN 978-0156716109).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "National Book Awards – 1962". National Book Foundation. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ↑ Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities (Harcourt, 1938, ASIN B003W00RVC).

- ↑ Richard T. LeGates and Frederic Stout (eds.), The City Reader (Routledge Urban Reader Series, 2011, ISBN 978-0415556651, 91.

- ↑ Lewis Mumford, The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects (New York, 1961), 464.

- ↑ Frank Jewett Mather Award The College Art Association. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ↑ Colin Ward, Influences Voices of Creative Dissent (Green Books, 1992, ISBN 978-1870098434), 106–107.

- ↑ Derek Wall, (ed.), Green History: A Reader in Environmental Literature, Philosophy and Politics (Routledge, 1993, ISBN 978-0415079259), 91.

- ↑ Ramachandra Guha and J. Martinez-Alier, Varieties of Environmentalism: Essays North and South (London: Earthscan, 1997).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Guha, Ramachandra, and Joan Martínez Alier. Varieties of Environmentalism: Essays North and South. Routledge, 1997. ISBN 978-1853833298

- Hughes, Thomas P., and Agatha C. Hughes (eds.). Lewis Mumford: Public Intellectual. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. ISBN 019506173X

- Lasch, Christopher. "Lewis Mumford and the Myth of the Machine," Salmagundi, 49, Summer 1980.

- LeGates, Richard T., and Frederic Stout (eds.). The City Reader. Routledge Urban Reader Series, 2011. ISBN 978-0415556651

- McClay, Wilfred M., and Ted V. McAllister (eds). Why Place Matters: Geography, Identity, and Civic Life in Modern America. Encounter Books, 2014. ISBN 978-1594037160

- Miller, Donald L. Lewis Mumford: A Life. New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1989. ISBN 978-1555842444

- Minteer, Ben A. The Landscape of Reform: Civic Pragmatism and Environmental Thought in America. The MIT Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0262512558

- Nicholson, Max. The New Environmental Age. Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0521379922

- Pepper, David. Modern Environmentalism: An Introduction. Routledge, 1996. ISBN 978-0415057455

- Wadlow, Rene. Lewis Mumford (1895-1990) Urbanization, Basic Needs, and an Organic View of the City Ovi Magazine (October 19, 2015). Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- Wall, Derek (ed.). Green History: A Reader in Environmental Literature, Philosophy and Politics. Routledge, 1993. ISBN 978-0415079259

- Ward, Colin. Influences : Voices of Creative Dissent. Green Books, 1992. ISBN 978-1870098434

External links

All links retrieved October 25, 2022.

- Mumford, Lewis. Gentlemen: You are Mad! Saturday Review of Literature March 2, 1946, 5–6.

- Lewis Mumford: A Brief Biography by Eugene Halton

- Lewis Mumford Center at the University at Albany, The State University of New York

- Virtual Lewis Mumford Library Mumford Archive at Monmouth University

- Works by Lewis Mumford at Open Library

- Works by Lewis Mumford at Unz.org

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.