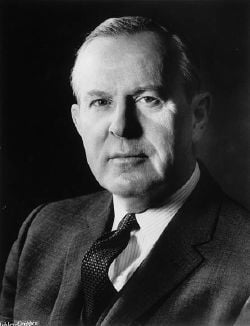

Lester B. Pearson

| Lester Bowles Pearson | |

| |

14th Prime Minister of Canada

| |

| In office April 22, 1963 – April 20, 1968 | |

| Preceded by | John Diefenbaker |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Pierre Elliott Trudeau |

| Born | April 23, 1897 Newtonbrook, Ontario |

| Died | December 27 1972 (aged 75) Ottawa, Ontario |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse | Maryon Pearson |

| Religion | United Church of Canada |

Lester Bowles Pearson, often referred to as "Mike," PC, OM, CC, OBE, MA, LL.D. (April 23, 1897 – December 27, 1972) was a Canadian statesman, diplomat, and politician, who, in 1957, became the first Canadian to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the fourteenth Prime Minister of Canada from April 22, 1963, until April 20, 1968, as the head of two back-to-back minority governments following elections in 1963 and 1965.

During his time as Prime Minister, Pearson's minority governments introduced universal health care, student loans, the Canada Pension Plan and Canada's flag. He improved pensions, and waged a "war on poverty." He pursued bipartisan foreign policy supporting internationalism, that is, economic and political cooperation among the nations of the world so that all benefit. During his tenure, Prime Minister Pearson also convened the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism. In 1969, he chaired a major inquiry for the World Bank. With these accomplishments, together with his groundbreaking work at the United Nations, and in international diplomacy, Pearson can safely be regarded as one of the most influential Canadians of the twentieth century.

Early years

Lester B. Pearson was born in Newtonbrook, Ontario (now a neighbourhood of Toronto), the son of Edwin Arthur Pearson, a Methodist (later United Church of Canada) minister and Anne Sarah Bowles. He entered Victoria College at the University of Toronto in 1914, where he lived in residence in Gate House and shared a room with his brother, Duke. While at the University of Toronto, he joined The Delta Upsilon Fraternity. At the university, he became a noted athlete, excelling in rugby and playing for the Oxford University Ice Hockey Club.

First World War

As he was too young to enlist in the army when the First World War broke out in 1914, he volunteered for the medical corps, where as a Lieutenant, he served two years in Egypt and Greece. In 1917, Pearson transferred to the Royal Flying Corps (as the Royal Canadian Air Force did not exist at that time), where he served as a Flying Officer until being sent home, as the result of a bus accident. It was as a pilot that he received the nickname of "Mike," given to him by a flight instructor who felt that "Lester" was too mild a name for an airman. Thereafter, Pearson would use the name "Lester" on official documents and in public life, but was always addressed as "Mike" by friends and family.

While training as a pilot at an air training school in Hendon, England, Pearson survived an airplane crash during his first flight but, unfortunately was hit by a London bus during a blackout and was sent home as an invalid to recuperate.

Interwar years

After the war, he returned to school, receiving his BA from the University of Toronto in 1919. Upon receiving a scholarship, he studied at St John's College Oxford University, where he received a BA in modern history in 1923, and the MA in 1925. In 1925, he married Maryon Moody (1901–1989), with whom he had one daughter, Patricia, and one son, Geoffrey.

After Oxford, he returned to Canada and taught history at the University of Toronto, where he also coached the men's varsity ice hockey team. He then embarked on a career in the Department of External Affairs. He had a distinguished career as a diplomat, including playing an important part in founding both the United Nations and NATO. During the Second World War, he once served as a courier with the codename "Mike." He went on to become the first director of Signal Intelligence. He served as Chair of the Interim Commission for Food and Agriculture from 1943 until the Food and Agriculture Organization was established in 1945. He also helped to set up the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (1943) serving as chair of the supply committee and of its subcommittee for displaced persons. In 1945, he advised the Canadian delegation at the San Fransisco conference where the UN Charter was drawn up. He argued against the concept of a Security Council veto for the "great powers." In 1947, as the UN considered the issue of Palestine, where Britain was withdrawing from its mandate, he chaired the UN's Political Committee. In 1952, Pearson was President of the General Assembly.

Political career

In 1948, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent appointed Pearson Minister of External Affairs in the Liberal government. Shortly afterward, he won a seat in the Canadian House of Commons, for the federal riding of Algoma East. In 1957, for his role in defusing the Suez Crisis through the United Nations, Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The selection committee claimed that Pearson had "saved the world." Presenting the Prize, Gunnar Jahn cited Pearson's own words to illustrate his motivation and philosophy for peacemaking:

"We are now emerging into an age," Lester Pearson says, "when different civilizations will have to learn to live side by side in peaceful interchange, learning from each other, studying each other's history and ideals, art and culture, mutually enriching each other's lives. The only alternative in this overcrowded little world is misunderstanding, tension, clash, and—catastrophe."[1]

Referring to the European Economic Community, he asked:

Is it any more visionary to foresee a further extension of this cooperative economic pattern? Is it not time to begin to think in terms of an economic interdependence that would bridge the Atlantic, that would at least break down the barrier between dollar and non-dollar countries which, next only to Iron Curtains, has hitherto most sharply divided our postwar One World?

The spread of democracy, too, would assist peace building but he was well aware that without "progress in living standards" no democracy could survive.

The United Nations Emergency Force was Pearson's creation, and he is considered the father of the modern concept of peacekeeping. In accepting the prize, Pearson spoke of the link between economic prosperity and peace, suggesting that while wealth does not prevent nations from going to war, "poverty" and "distress" and nonetheless major factors in causing international tension. He cited Arnold Toynbee, who had "voiced this hope and this ideal when he said: 'The twentieth century will be chiefly remembered by future generations not as an era of political conflicts or technical inventions, but as an age in which human society dared to think of the welfare of the whole human race as a practical objective.'"[2] His own work with the Food and Agricultural Organization and in Relief and Rehabilitation helped to remove obstacles to the creation of stable democracies and peace-affirming societies.

Party leadership

He was elected leader of the Liberal Party at its 1958 leadership convention but his party was badly routed in the election of that year. As the newly elected leader of the Liberals, Mr. Pearson had given a speech in Commons that asked Mr. Diefenbaker to give power back to the Liberals without an election, because of a recent economic downturn. This strategy backfired when Mr. Diefenbaker seized on the error by showing a classified Liberal document saying that the economy would face a downturn in that year. This contrasted heavily with the Liberals' 1957 campaign promises, and would make sure the "arrogant" label would remain attached to the Liberal party. The election also cost the Liberals their Quebec stronghold; the province had voted largely Liberal in federal elections since the Conscription Crisis of 1917, but upon the resignation of former Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent, the province had no favorite son leader, as they had since 1948.

In the 1962 election, his party reduced the Progressive Conservative Party of John Diefenbaker to a minority government.

Not long after the election, Pearson capitalized on the Conservatives' indecision on installing nuclear warheads on Bomarc missiles. Minister of National Defense Douglas Harkness resigned from Cabinet on February 4, 1963, because of Diefenbaker's opposition to accepting the missiles. The next day, the government lost two non-confidence motions on the issue, prompting the election.

Prime Minister

Pearson led the Liberals to a minority government in the 1963 general election, and became prime minister. He had campaigned during the election promising "60 Days of Decision" and support for the Bomarc missile program.

Pearson never had a majority in the Canadian House of Commons, but he introduced important social programs (including universal health care, the Canada Pension Plan, Canada Student Loans) and the Maple Leaf Flag (known as the Great Flag Debate). Pearson's government instituted many of the social programs that Canadians hold dear. This was due in part to support for his minority government in the House of Commons from the New Democratic Party, led by Tommy Douglas. His actions included instituting the 40 hour work week, two weeks vacation time, and a new minimum wage.

Pearson signed the Canada-United States Automotive Agreement (or Auto Pact) in January 1965, and unemployment fell to its lowest rate in over a decade.

While in office, Pearson resisted U.S. pressure to enter the Vietnam War. Pearson spoke at Temple University in Philadelphia on April 2, 1965, while visiting the United States, and voiced his support for a negotiated settlement to the Vietnam War. When he visited U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson the next day, Johnson (supposedly) strongly berated Pearson. Pearson later recounted that the meeting was acrimonious, but insisted the two parted cordially. After this incident, LBJ and Pearson did have further contacts, including two further meetings together, both times in Canada. (Canadians most remember the Pearson years as a time Canada-U.S. relations greatly improved.)

Pearson also started a number of Royal Commissions, including one on the status of women and another on bilingualism. They instituted changes that helped create legal equality for women, and brought official bilingualism into being. After Pearson, French was made an official language, and the Canadian government would provide services in both. Pearson himself had hoped that he would be the last unilingual Prime Minister of Canada and, indeed, fluency in both English and French became an unofficial requirement for Prime Ministeral candidates after Pearson left office.

Pearson was also remarkable for instituting the world's first race-free immigration system, throwing out previous ones that had discriminated against certain people, such as Jews and the Chinese. His points-based system encouraged immigration to Canada, and a similar system is still in place today.

Pearson also oversaw Canada's centennial celebrations in 1967, before retiring. The Canadian news agency, Canadian Press, named him "Newsmaker of the Year" that year, citing his leadership during the centennial celebrations, which brought the Centennial Flame to Parliament Hill.

Also in 1967, the President of France, Charles de Gaulle made a visit to Quebec. During that visit, de Gaulle was a staunch advocate of Quebec separatism, even going so far as to say that his procession in Montreal reminded him of his return to Paris after it was freed from the Nazis during the Second World War. President de Gaulle also gave his "Vive le Québec libre" speech during the visit. Given Canada's efforts in aid of France during both world wars, Pearson was enraged. He rebuked de Gaulle in a speech the following day, remarking that "Canadians do not need to be liberated" and making it clear that de Gaulle was no longer welcome in Canada. The French President returned to his home country and would never visit Canada again.

Supreme Court appointments

Pearson chose the following jurists to be appointed as justices of the Supreme Court of Canada by the Governor General:

- Robert Taschereau (as Chief Justice, (April 22, 1963–September 1, 1967; appointed a Puisne Justice under Prime Minister King, February 9, 1940)

- Wishart Flett Spence (May 30, 1963–December 29, 1978)

- John Robert Cartwright (as Chief Justice, (September 1, 1967–March 23, 1970; appointed a Puisne Justice under Prime Minister St. Laurent, December 22, 1949)

- Louis-Philippe Pigeon (September 21, 1967-February 8, 1980)

Retirement

After his announcement on December 14, 1967, that he was retiring from politics, a leadership convention was held. Pearson's successor was Pierre Trudeau, a man who Pearson had recruited and made Minister of Justice in his cabinet. Trudeau later became Prime Minister, and two other cabinet ministers Pearson recruited, John Turner and Jean Chrétien, served as prime ministers in the years following Trudeau's retirement. Paul Martin Jr., the son of Pearson's minister of external affairs, Paul Martin Sr., also went on to become prime minister.

From 1969 to until his death in 1972, Pearson served as Chancellor of Carleton University in Ottawa. Pearson headed up a major study on aid and development, the Pearson Commission for the World Bank which examined the previous 20 years of development assistance. The Report was published in September 1969, and recommended increased funding for development which, however, should be scrutinized for transparency and effectiveness.

Honors and awards

- The Canadian Press named Pearson "Newsmaker of the Year" 9 times, a record he held until his successor, Pierre Trudeau, surpassed it in 2000. He was also only one of two prime ministers to have received the honor, both before and when prime minister (The other being Brian Mulroney).

- The Lester B. Pearson Award is awarded annually to the National Hockey League's outstanding player in the regular season, as judged by members of the NHL Players Association (NHLPA). It was first awarded in 1971, to Phil Esposito, a native of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

- The Lester B. Pearson Building, completed in 1973, is the headquarters for Foreign Affairs Canada, a tribute to his service as external affairs minister.

- Lester B. Pearson College, opened in 1974, is a United World College near Victoria, British Columbia.

- The Pearson Medal of Peace, first awarded in 1979, is an award given out annually by the United Nations Association in Canada to recognize an individual Canadian's "contribution to international service."

- Toronto Pearson International Airport, first opened in 1939 and re-christened with its current name in 1984, is Canada's busiest airport.

- The Pearson Peacekeeping Centre, established in 1994, is an independent not-for-profit institution providing research and training on all aspects of peace operations.

- The Lester B. Pearson School Board is the largest English-language school board in Quebec. The majority of the schools of the Lester B. Pearson School Board are located on the western half of island of Montreal, with a few of its schools located off the island as well.

- Lester B. Pearson High School lists five so named schools, in Calgary, Toronto, Burlington, Ottawa, and Montreal. There are also schools (also Elementary) in Ajax, Ontario, Aurora, Ontario, Brampton, Ontario, London, Ontario, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Waterloo, Ontario and Wesleyville, Newfoundland.

- Pearson Avenue is located near Highway 407 and Yonge Street in Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada; less than five miles from his place of birth.

- Pearson Way is an arterial access road located in a new subdivision in Milton, Ontario; many ex-Prime Ministers are being honoured in this growing community, including Prime Ministers Trudeau and Laurier.

- Lester B. Pearson Place, completed in 2006, is a four story affordable housing buildng in Newtonbrook, Ontario, mere steps from his place of birth.

- A plaque at the north end of the North American Life building in North York commemorates his place of birth. The manse where Pearson was born is gone, but a plaque is located at his birth site

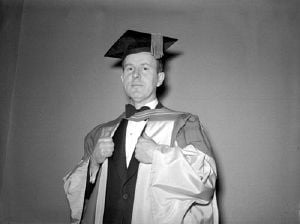

Honorary Degrees

Lester B. Pearson received Honorary Degrees from 48 Universities, including:

- University of Toronto in 1945 (LL.D)

- University of Rochester in 1947 (LL.D)

- McMaster University in 1948 (LL.D)

- Bates College in 1951 (LL.D)

- Princeton University in 1956 (LL.D)

- University of British Columbia in 1958 (LL.D)

- University of Notre Dame in 1963

- Waterloo Lutheran University later changed to Wilfrid Laurier University in 1964 (LL.D)

- Memorial University of Newfoundland in 1964 (LL.D)

- Johns Hopkins University in 1964 (LL.D)

- University of Western Ontario in 1964

- Laurentian University in 1965 (LL.D)

- University of Saskatchewan (Regina Campus) later changed to University of Regina in 1965

- McGill University in 1965 [

- Queen's University in 1965 (LL.D)

- Dalhousie University in 1967 (LL.D)

- University of Calgary in 1967

- UCSB in 1967

- Harvard University

- Columbia University

- Oxford University (LL.D)

Legacy

Pearson helped to shape the Canadian nation. His bilingual policy was designed to hold the nations two main linguisytic ansd cultural communities together. His international philosophy and strong support for United Nations peacekeeping has continued to feature in Canada's participation in numerous peace keeping missions and in her reluctance to support non-UN sanctioned conflict, such as the 2003 invasion of Iraq and in Canada's advocacy of assistance to the developing world as a moral duty, which the Pearson report had argued. An official Canadian website describes development assistance as one of "the clearest international expressions of Canadian values and culture - of Canadians' desire to help the less fortunate and of their strong sense of social justice - and an effective means of sharing these values with the rest of the world".[3] These words could have been written by Pearson, echoing his 1957 Nobel Lecture.

Notes

- ↑ Gunnar Jahn, The Nobel Peace Prize, 1957, Norwegian Nobel Committee. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- ↑ Lester B. Pearson, Nobel Lecture, 1957. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- ↑ Foreign Affairs and International Assistance, Canada, International Assistance. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beal, John Robinson. Pearson of Canada. 1964.

- Beal, John Robinson and Jean-Marc Poliquin. Les trois vies de Pearson of Canada. 1968.

- Bothwell, Robert. Pearson, His Life and World. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1978. ISBN 0-07-082305-7

- Champion, C.P. "A Very British Coup: Canadianism, Quebec and Ethnicity in the Flag Debate, 1964-1965." Journal of Canadian Studies 40.3 (2006): 68-99.

- English, John. Shadow of Heaven: The Life of Lester Pearson, Volume I, 1897-1948. Toronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1989. ISBN 0-88619-169-6

- English, John. The Worldly Years: The Life of Lester Pearson, Volume II, 1949-1972. Toronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1992. ISBN 0-394-22729-8

- Fry, Michael G. Freedom and Change: Essays in Honour of Lester B. Pearson. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1975. ISBN 0-7710-3187

- Pearson, Lester B. Canada: Nation on the March. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1953.

- —. The Crisis of Development. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1970.

- —. Diplomacy in the Nuclear Age. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1959.

- —. The Four Faces of Peace and the International Outlook. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1964.

- —. Mike : The Memoirs of the Right Honourable Lester B. Pearson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972. ISBN 0-575-01709-0

- —. Peace in the Family of Man. London: Oxford University Press, 1969. ISBN 0-563-08449-9

- —. Words and Occasions: An Anthology of Speeches and Articles, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1970. ISBN 0-674-95611-7

- Stursberg, Peter. Lester Pearson and the Dream of Unity. Toronto: Doubleday, 1978. ISBN 0-385-13478-9

- Thordarson, Bruce. Lester Pearson: Diplomat and Politician. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1974. ISBN 0-19-540225-1

External links

All links retrieved October 25, 2022.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.