Kwakwaka'wakw

| Kwakwaka'wakw |

|---|

|

| Total population |

| 5,500 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Canada (British Columbia) |

| Languages |

| English, Kwak'wala |

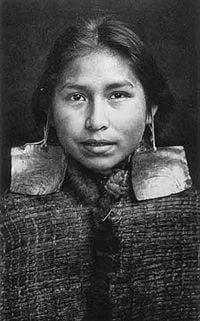

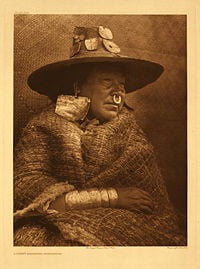

| Religions |

The Kwakwaka'wakw (also Kwakiutl) are a Pacific Northwest coast people. Kwakwaka'wakw translates into "Kwak'wala speaking tribes," describing the original 17 tribes within their nation who originally spoke the Kwak'wala language. They live in British Columbia on northern Vancouver Island and the mainland, and number approximately 5,500.

Their society was highly stratified, with several classes: Nobles and aristocrats, commoners, and slaves. Their lifestyle was based primarily on fishing, with the men also engaging in hunting, and the women gathering wild fruits and berries. Ornate woodwork was an important craft, used in carving totem poles and ceremonial masks as well as the more practical canoes. Wealth, defined by numbers of slaves as well as material goods, was prominently displayed and exchanged at potlatch ceremonies.

After contact with outsiders, their numbers were drastically reduced by disease, and their lifestyle forcibly changed in efforts to "Christianize" and "civilize" them. Notably, the potlatch was banned for many years. In contemporary times, the Kwakwaka'wakw have been active in the revitalization of their culture and language, and their artwork, particularly the totem poles, has been recognized and widely appreciated.

Name

The name Kwakiutl was applied to a group of indigenous peoples of northern Vancouver Island, Queen Charlotte Strait, and the Johnstone Strait. They are now known as Kwakwaka'wakw, which means "Kwak'wala-speaking-peoples." The term "Kwakiutl," created by anthropologist Franz Boas, was widely used into the 1980s. It comes from one of the Kwakwaka'wakw tribes, the Kwagu'ł, at Fort Rupert, with whom Boas did most of his work. The term was misapplied to mean all the tribes who spoke Kwak'wala, as well as three other indigenous peoples whose language is a part of the Wakashan linguistic group, but whose language is not Kwak'wala. These peoples, incorrectly known as the Northern Kwakiutl, are the Haisla, Wuikinuxv, and Heiltsuk.

History

The ancient homeland of the Kwakwaka'wakw was in Vancouver Island, smaller islands, and the adjacent coastland that is now part of British Columbia, Canada.

The tribes

Kwakwaka'wakw were historically organized into 17 different tribes. Each tribe had its own clans, chiefs, history, and culture, but remained collectively similar to the rest of the Kwaka'wala speaking tribes. The tribes and their locations are Kwaguʼł (Fort Rupert), Mama̱liliḵa̱la (Village Island), ʼNa̱mǥis (Cheslakees), Ławitʼsis (Turnour Island), A̱wa̱ʼetła̱la (Knight Inlet), Da̱ʼnaxdaʼx̱w (New Vancouver), Maʼa̱mtagila (Estekin), Dzawada̱ʼenux̱w (Kincome Inlet), Ḵwikwa̱sutinux̱v (Gilford Island), Gwawaʼenux̱w (Hopetown), ʼNakʼwaxdaʼx̱w (Blunden Harbour), Gwaʼsa̱la (Smiths Inlet), G̱usgimukw (Quatsino), Gwatʼsinux̱w (Winter Harbour), Tłatła̱siḵwa̱la (Hope Island), Weḵaʼyi (Cape Mudge), Wiweḵʼa̱m (Campbell River).[2]

After European contact, although some of these tribes became extinct or merged, most have survived.

Contact with Europeans

In the 1700s, Russian, British, and American trading ships visited the Kwakwaka'wakw territory. The first documented contact was with Captain George Vancouver in 1792. The settlement of Victoria on Vancouver Island in 1843 was the turning point of outside impact on Kwakwaka'wakw life.

Diseases brought by Europeans drastically reduced the indigenous Kwakwaka'wakw population during the late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Alcohol, missionaries, and the banning of potlatches significantly changed Kwakwaka'wakw culture. When anthropologist Franz Boas began his research on the Kwakwaka'wakw people, he was met with suspicion as they had learned that white people intended to change their lifestyle. O’wax̱a̱laga̱lis, chief of the Kwagu'ł of Fort Rupert, on meeting Boas on October 7, 1886 said:

We want to know whether you have come to stop our dances and feasts, as the missionaries and agents who live among our neighbors try to do. We do not want to have anyone here who will interfere with our customs. We were told that a man-of-war would come if we should continue to do as our grandfathers and great-grandfathers have done. But we do not mind such words. Is this the white man’s land? We are told it is the Queen’s land, but no! It is mine.

Where was the Queen when our God gave this land to my grandfather and told him, “This will be thine?” My father owned the land and was a mighty Chief; now it is mine. And when your man-of-war comes, let him destroy our houses. Do you see yon trees? Do you see yon woods? We shall cut them down and build new houses and live as our fathers did.

We will dance when our laws command us to dance, and we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, “Do as the Indian does?” It is a strict law that bids us dance. It is a strict law that bids us distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you come to forbid us dance, be gone. If not, you will be welcome to us.[3]

Culture

The Kwakwaka'wakw are a highly stratified bilineal culture of the Pacific Northwest. The Kwakwaka'wakw were made up of 17 separate tribes, each with their own history, culture, and governance.

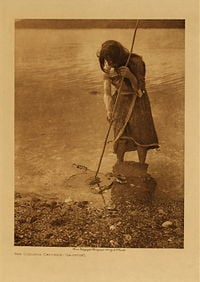

Generally, their culture was typical of Northwest Coast Indians. They were fishers, hunters and gatherers, and traded with neighboring peoples.

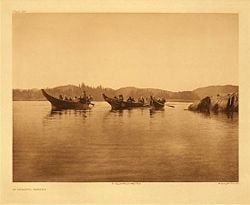

Kwakwaka'wakw transportation was like other coastal peoples—their main way of travel was by canoe. Cedar dug out canoes, made from one cedar log, were carved to be used by individuals, families, and tribes. Sizes varied from ocean-going canoes for long sea-worthy travel for trading, to smaller local canoes for inter-village travel.

Living in the coastal regions, seafood was a staple of their diet, supplemented by berries. Salmon was a major catch during spawning season. In addition, they sometimes went whale harpooning on trips that could last many days.

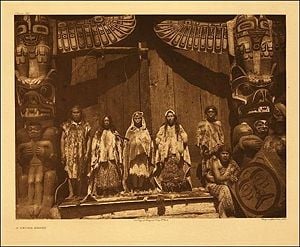

Their houses were made from cedar-plank. They were very large, up to 100 feet (30 m), and could hold about 50 people, usually families from the same clan. In the entrance, there was usually a totem pole decorated with crests belonging to their family and clan. Kwakwaka'wakw are known, along with the Haida, as skilled carvers of totem poles and ceremonial masks.

The year was divided into two parts: The spring and summer were the active times involving fishing, hunting, gathering, and preserving food; these were the secular times of travel. The winter saw people return to their villages, suspending physical activities and focusing on the spiritual or supernatural aspects of life, living together in their large houses and performing religious ceremonies.[4] Their belief system was complex, involving many ceremonies and rituals, and they practiced the potlatch.

Language

Kwak'wala is the indigenous language spoken by the Kwakwaka'wakw. It belongs to the Wakashan language family. The ethnonym Kwakwaka'wakw literally means "speakers of Kwak'wala," effectively defining an ethnic connection by reference to a shared language. However, the Kwak'wala spoken by each of the surviving tribes with Kwak'wala speakers exhibits dialectical differences. There are four major dialects which are unambiguously dialects of Kwak'wala: Kwak̓wala, ’Nak̓wala, G̱uc̓ala, and T̓łat̓łasik̓wala.[5]

In addition to these dialects, there are also Kwakwaka'wakw tribes that speak Liq'wala. Liq'wala has sometimes been considered to be a dialect of Kwak'wala, and sometimes a separate language. The standard orthography for Liq'wala is quite different from the most widely-used orthography for Kwak'wala, which tends to widen the apparent differences between Liq'wala and Kwak'wala.

The Kwak'wala language is a part of the Wakashan language group. Word lists and some documentation of Kwak'wala were created from the early period of contact with Europeans in the eighteenth century, but a systematic attempt to record the language did not occur before the work of Franz Boas in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The use of Kwak'wala declined significantly in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, mainly due to the assimilationist policies of the Canadian government, and above all the mandatory attendance of Kwakwa'wakw children at residential schools. Although Kwak'wala and Kwakwaka'wakw culture have been well-studied by linguists and anthropologists, these efforts did not reverse the trends leading to language loss. According to Guy Buchholtzer, "The anthropological discourse had too often become a long monologue, in which the Kwakwaka'wakw had nothing to say."[6] As a result of these pressures, there are relatively few Kwak'wala speakers today, and most remaining speakers are past the age of child-rearing, which is considered crucial for language transmission. As with many other indigenous languages, there are significant barriers to language revitalization.[7]

There are about 250 Kwak'wala speakers today, which is approximately five percent of the Kwakwaka'wakw population. Because of the small number of speakers, and the fact that very few children learn Kwak'wala as a first language, its long-term viability is in question. However, interest from many Kwakwaka'wakw in preserving their language and a number of revitalization projects are countervailing pressures which may extend the viability of the language.

Social structure

Kwakwa'wakw society was assembled into four classes, the nobility, attained through birthright and connection in lineage to ancestors, the aristocracy who attained status through connection to wealth, resources, or spiritual powers displayed or distributed in the potlatch, the commoners, and the slaves. The nobility were very special, as "the noble was recognized as the literal conduit between the social and spiritual domains, birth right alone was not enough to secure rank: only individuals displaying the correct moral behavior throughout their life course could maintain ranking status."[8]

Commonly among the tribes, there would be a tribal chief, who acted as the head chief of the entire tribe, then below him numerous clan or family chiefs. In some of the tribes, there also existed "Eagle Chiefs," but this was a separate society within the main society and applied to the potlatching only.

The Kwakwaka'wakw are one of the few bilineal cultures. Traditionally the rights of the family would be passed down through the paternal side, but in rare occasions, one could take the maternal side of their family also.

Potlatch

The Kwakwaka'wakw were prominent in the potlatch culture of the Northwest, and are the main group who continue to celebrate it today. Potlatch takes the form of a ceremonial feast traditionally featuring seal meat or salmon. It commemorates an important event, such as the death of a high-status person, but expanded over time to celebrate events in the life cycle of the host family, such as the birth of a child, the start of a daughter's menstrual cycle, and even the marriage of children.

Through the potlatch, hierarchical relations within and between groups were observed and reinforced through the exchange of gifts, dance performances, and other ceremonies. The host family demonstrated their wealth and prominence through giving away their possessions and thus prompting prominent participants to reciprocate when they held their own potlatches. The Kwakwaka'wakw developed a system whereby the recipient of a gift had to repay twice as much at the next potlatch. This meant that the potlatch was not always used to honor friends or allies, but to humiliate enemies or rivals as they could be forced to give away all their possessions to repay what they owed at a potlatch.[9] In contrast to European societies, wealth for the Kwakwaka'wakw was not determined by how much an individual possessed, but by how much he could give away.

The potlatch was a key target in assimilation policies and agendas. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was “by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized.”[10] Thus in 1885, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the potlatch and making its practice illegal. Legislation was then expanded to include guests who participated in the ceremony. However, enforcement was difficult and Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offense from criminal to summary, which meant "the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence."[11]

Arts

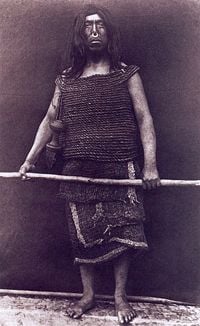

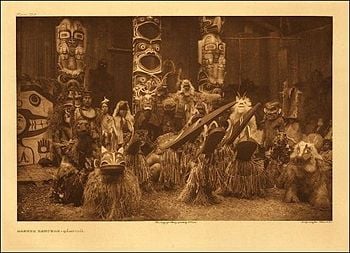

In the old times, the art “symbolized the essential consanguinity of all living beings beneath the mask of their particular species.”[12] Masks, costumes, crests, and totem poles express Kwakwaka'waka in static form; songs, speeches, and dialogues use vocal form; and drama and dance use motion.[4]

The Kwakwaka'waka were masters the arts of wood carving, dance, and theater. Elaborate masks and robes were significant features of their ceremonies and theatrical performances. Totem poles communicated a family history through its crests—derived from legend they represent an ancestor who became or encountered a mythical being.

Totem poles

Totem poles are monumental sculptures carved from great trees, typically Western Redcedar, by a number of Northwest Coast Indians including the Kwakwaka'wakw. Totem poles may recount familiar legends, clan lineages, or notable events. Some poles are erected to celebrate cultural beliefs, but others are intended mostly as artistic presentations. Poles are also carved to illustrate stories, to commemorate historic persons, to represent shamanic powers, and to provide objects of public ridicule.

The "totems" on the poles are animals, sea creatures, or other objects, natural or supernatural, which provide deeply symbolic meaning for the family or clan. A totem is revered and respected, but not necessarily worshiped. Totem poles were never objects of worship; the association with "idol worship" was an idea from local Christian missionaries who regarded the totem pole, along with the potlatch, as an aspect of their lifestyle that needed to be eradicated in order to fully "Christianize" the people.

Today, totem poles are recognized as an amazing artistic form, and carvers are again respected as playing a valuable role not only in the Kwakwaka'wakw culture but in other societies.

Masks

As well as carving totem poles, the Kwakwaka'wakw carved magnificent masks, often representing creatures from their mythology. The wooden masks were painted, adorned with feathers and hair, and each was unique. Some masks had movable parts, such as mouths or beaks, which could be opened and closed when they were used in storytelling.

These "transformation masks" reflect traditional Kwakwaka'wakw beliefs. In the ancient times it was said that birds, fish, animals, and human beings differed only in their skin covering, and were able to transform themselves into these different forms. They could also become supernatural beings. When a dancer puts on a mask, they are transformed into the being represented on the mask, and when it is opened revealing a different creature, they transform into that being.

The most famous masks were used in the Hamatsa rituals, the "cannibal" dances which involved large man-eating birdlike creatures.

Music

Kwakwaka'wakw music is an ancient art form, stretching back thousands of years. The music is used primarily for ceremony and ritual, and is based around percussive instrumentation, especially, log, box, and hide drums, as well as rattles and whistles. The four-day Klasila festival is an important cultural display of song and dance, occurring just before the advent of the tsetseka, or winter.

Mythology

As the Kwakwaka'wakw are made up of all the Kwak'wala speaking tribes, a variety of beliefs, stories, and practices exist. Some origin stories belong to only one specific tribe. However, many practices, rituals, and ceremonies are occurrences through all of Kwakwaka'wakw culture, and in some cases, neighboring indigenous cultures also.

Creation story

The Kwakwaka’wakw creation story is that the ancestor of a ‘na’mima—the extended family unit having specific responsibilities within each tribe—appeared at a specific location by coming down from the sky, out of the sea, or from underground. Generally in the form of an animal, it would take off its animal mask and become a person. The Thunderbird or his brother Kolus, the Gull, the Killer Whale (Orca), a sea monster, a grizzly bear, and a chief ghost would appear in this role. In a few cases, two such beings arrived, and both would become ancestors. There are a few ‘na’mima that do not have the traditional origin, but are said to have come as human beings from distant places. These ancestors are called “fathers” or “grandfathers,” and the myth is called the “myth at the end of world.”[13]

Flood

Like all Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, most of the Kwakwaka'wakw tribes have stories about their people surviving a great flood. Some have stories of their people attaching their ocean-going canoes to tall mountains. With others, their history talks of their ancestors transforming into their natural form and disappearing while the waters rose and then subsided. For these stories involving supernatural powers, these figures tend to be the founding Kwakwaka'wakw clans.

Spiritual beings

Kwakwaka'wakw spirits, like those of other Northwest Coast peoples, can be divided into four separate spirit realms, including sky spirits, sea spirits, earth spirits, and otherworldly spirits. All four realms interact with one another, and human beings attempt to contact them at sacred ceremonies wherein dancers go into trances while wearing masks and other regalia associated with the spirit world. Examples of these spiritual beings include:

- Tseiqami

Tseiqami is Thunderbird, lord of the winter dance season, a massive supernatural bird whose wing beats cause the thunder, and the flash of whose eyes causes lightning. Thunderbird also has a younger brother named Kolus.

- Qaniqilak

Thunderbird's adversary is Qaniqilak, spirit of the summer season, who is often identified as the sea god, Kumugwe the "Undersea Chief."

- Sisiutl

Sisiutl is a giant three-headed sea serpent whose glance can turn an adversary into stone.

- Dzunukwa

Dzunukwa (Tsonokwa) is a type of cannibal giant (called sasquatch by other Northwest Coast tribes) and comes in both male and female forms. In most legends, the female form is the most common; she eats children and imitates the voice of the child's grandmother to attract them. Children frequently outwit her, though, sometimes killing her and taking her treasures without being eaten.

- Bakwas

Bakwas is king of the ghosts. He is a small green spirit whose face looks emaciated like a skeleton, but has a long curving nose. He haunts the forests and tries to bring the living over to the world of the dead. In some myths Bakwas is the husband of Dzunukwa.

- U'melth

U'melth is the Raven, who brought the Kwakwaka'wakw people the moon, fire, salmon, the sun, and the tides.

- Pugwis

'Pugwis' is an aquatic creature with fish-like face and large incisors.

Hamatsa

Of particular importance in Kwakwaka'wakw culture is the secret society called Hamatsa. During the winter, there is a four-day, complex dance ceremony that serves to initiate new members into the society. It is often called a "cannibal" ritual, and some have suggested that the Kwakwaka'wakw actually practiced ritual cannibalism, while others regarded their "cannibalism" as purely symbolic, with the ceremony showing the evil of cannibalism and thus discouraging it.[9]

The dance is based on the story of brothers who became lost on a hunting trip and found a strange house with red smoke emanating from its roof. When they visited the house they found its owner gone. One of the house posts was a living woman with her legs rooted into the floor, and she warned them about the owner of the house, who was named Baxbaxwalanuksiwe, a man-eating giant with four terrible man-eating birds for his companions. The brothers are able to destroy the man-eating giant and gain mystical power and supernatural treasures from him.

Prior to the ceremony, the Hamatsa initiate, almost always a young man, is abducted by members of the Hamatsa society and kept in the forest in a secret location where he is instructed in the mysteries of the society. At the winter dance festival the initiate is brought in wearing spruce bows, gnashing his teeth, and even biting members of the audience who include members of many clans and even neighboring tribes. Many dances ensue, as the tale of Baxbaxwalanuksiwe is recounted, and all of the giant man-eating birds dance around the fire. Gwaxwgwakwalanuksiwe is the most prestigious role in the Supernatural Man-Eater Birds ceremony; he is a man-eating raven who ate human eyes. Galuxwadzuwus ("Crooked-Beak of Heaven") who ate human flesh, and Huxhukw (supernatural Crane-Like Bird), who cracks skulls of men to suck out their brains, are other participants.

Finally the society members succeed in taming the new "cannibal" initiate. In the process of the ceremonies what seems to be human flesh is eaten by the initiates. All persons who were bitten during the proceedings are gifted with expensive presents, and many gifts are given to all of the witnesses who are required to recall through their gifts the honors bestowed on the new initiate and recognize his station within the spiritual community of the clan and tribe.

Thus this ceremony can be interpreted as an example of what Victor Turner described as the coming together of the ideological and the sensory, the symbols bringing ethical norms into close contact with strong emotional stimuli.[14] Thus, the "cannibal" dance brings together images of hunger with moral rituals, saturating norms and values with emotion and regulating emotions with social order.[4]

Contemporary Kwakwaka'wakw

Contemporary Kwakwaka'wakw have made great efforts to revive their customs, beliefs, and language, restoring their ties to their land, culture, and rights. Potlatch occur more frequently as families reconnect to their birthright and commit to the restoring of the ways of their ancestors. Language programs, classes, and social events utilize the community to restore the language.

A number of revitalization efforts have recently attempted to reverse language loss for Kwak'wala. A proposal to build a Kwakwaka'wakw First Nations Centre for Language Culture has gained wide support.[6] A review of revitalization efforts in the 1990s shows that the potential to fully revitalize Kwak'wala still remains, but serious hurdles also exist.[15]

The U'mista Cultural Society was established in 1974, with the goal of ensuring the survival of all aspects of cultural heritage of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw. U'mista means "the return of something important," originally referring to what former captives of enemy tribes possessed when they returned to their people.[9] One of the society's projects is to house returned potlatch artifacts seized by government during the period of cultural repression. This effort has sparked a general trend toward the return of cultural artifacts, adding to the spirit of reconnecting to the ancestral ways and pride in Kwakwaka'wakw culture.

Notable Kwakwaka'wakw

- George Hunt

George Hunt was Tlingit by birth, but through marriage and adoption he became an expert on the traditions of the Kwakwaka'wakw. He carved a totem pole, Kwanusila, that was on display in a Chicago park for many decades until it had to be replaced; the carver of the replacement was his descendant Tony Hunt. George Hunt's descendants include a dynasty of traditional Northwest Coast artists including Henry Hunt, Richard Hunt, Stanley Hunt, Tony Hunt, and Calvin Hunt.

- Mungo Martin

Chief Mungo Martin or Nakapenkim (meaning a potlatch chief "ten times over"), was a noted expert in the Northwest Coast style of artwork, a singer, and a songwriter. Martin was responsible for the restoration and repair of many carvings and sculptures, totem poles, masks, and various other ceremonial objects. Martin also gained fame for holding the first public potlatch since the governmental potlatch ban of 1889. For this, he was awarded with a medal by the Canadian Council.[16] He also acted as a tutor to his son-in-law Henry Hunt and grandson Tony Hunt, thus combining his skill with the Hunt family of carvers.

- James Sewid

Chief James Sewid (1913-1988) was a fisherman, author, and Chief of the Nimpkish Band (‘Namgis First Nation) of Kwakwaka'wakw at Alert Bay, British Columbia. The name Sewid means "Paddling towards the chief that is giving a potlatch." At a potlatch when he was an infant, James received the additional name Poogleedee meaning "guests never leave his feasts hungry."[17] This name was used in the title of his autobiography Guests Never Leave Hungry.[18] As chief, Sewid was active in reviving Kwakwaka'wakw traditions, particularly the potlatch which had been outlawed. In 1955, he was selected by the National Film Board of Canada to portray many of his achievements in a film called No Longer Vanishing. In 1971, he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada "for his contributions to the welfare of his people and for fostering an appreciation of their cultural heritage."[19]

- Harry Assu

Chief Harry Assu (1905-1999), a chief of the Lekwiltok (Laich-kwil-tach)—the southernmost tribe of the Kwakwaka'wakw—from a Cape Mudge family renowned for its lavish potlatches. His father, Chief Billy Assu (1867-1965), was one of the most renowned chiefs of the Northwest who guided the Cape Mudge Band of the Lekwiltok from a traditional way of life into modern prosperity through developing a commercial fishing fleet. Both father and son were life-long fishermen and Chief Billy Assu was the first in his community to own a gas powered fishing boat. Harry Assu's boat, the BCP 45, was chosen for the design on the back of the Canadian five-dollar bill that was in circulation between 1972 and 1986.[20] In his book, Assu of Cape Mudge: Recollections of a Coastal Indian Chief, Assu recalled the 60 years of effort it took to restore the historic artifacts, potlatch regalia, taken in 1922 during the long period when the potlatch was outlawed.[21]

Popular culture

In the Land of the Head Hunters (also called In the Land of the War Canoes) is a 1914 silent documentary film, written and directed by Edward S. Curtis, showing the lives of the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples of British Columbia. In 1999 the film was deemed "culturally significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Notes

- ↑ Royal BC Museum, Thunderbird Park, Online Exhibits. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ↑ The Tribes U'mista Cultural Society. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ↑ Franz Boas, The Kwakiutl of British Columbia, a Documentary by Franz Boas (Bill Holm Center, 2007).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Martha Padfield, Cannibal Dances in the Kwakiutl World, Canadian Journal for Traditional Music, 1991. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ Christopher Harvey, Kwakwa̱ka̱'wakw/Kʷakʷəkəw̓akʷ Communities, languagegeek.com, 2008. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Susan Jamieson-McLarnon, "Native language centre planned," SFU News online Simon Fraser University, 33(6) (July 7, 2005). Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ↑ Joshua Fishman, "Conclusion: Maintaining Languages What Works? What Doesn't?," Stabilizing Indigenous Languages, edited by G. Cantoni (Flagstaff, AZ: Center for Excellence in Education, Northern Arizona University, 1996). Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ↑ Joseph Masco, "It Is a Strict Law That Bids Us Dance:" Cosmologies, Colonialism, Death, and Ritual Authority in the Kwakwaka'wakw Potlatch, 1849 to 1922, Comparative Studies in Society and History 37(1) (1995): 41. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Carl Waldman, Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0816062744).

- ↑ Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890 (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1992, ISBN 0774804009), 207.

- ↑ Aldona Jonaitis, Chiefly Feasts: the Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch (Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre, 1996. ISBN 1550544802), 159.

- ↑ Jonaitis, 67.

- ↑ Franz Boas, Contributions to the Ethnology of the Kwakiutl (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1925), 229-230.

- ↑ Victor Turner, The Forest of Symbols (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1969, ISBN 0801404320).

- ↑ Stan J. Anonby, "Reversing Language Shift: Can Kwak'wala Be Revived?" Chapter 4 of Revitalizing Indigenous Languages, edited by Jon Reyhner, Gina Cantoni, Robert N. St. Clair, and Evangeline Parsons Yazzie (Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University, 1999), 33-52. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ↑ Jeffrey D. Schultz, Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics (Greenwood Press, 2000, ISBN 1573561487).

- ↑ Sewid, James (Poogleedee) ABC Bookworld. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ↑ James P. Sewid, Guests Never Leave Hungry: The Autobiography of James Sewid, a Kwakiutl Indian (New Haven, CT: Yale University, 1969, ISBN 978-0300010756).

- ↑ James Sewid, O.C. Order of Canada. www.gg.ca Archives. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ↑ Assu, Harry ABC Bookworld. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ↑ Harry Assu, Assu of Cape Mudge: Recollections of a Coastal Indian Chief (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0774803335).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anonby, Stan J. "Reversing Language Shift: Can Kwak'wala Be Revived?" Chapter 4 of Revitalizing Indigenous Languages. Edited by Jon Reyhner, Gina Cantoni, Robert N. St. Clair, and Evangeline Parsons Yazzie. Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University, 1999, 33-52. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- Assu, Harry. Assu of Cape Mudge: Recollections of a Coastal Indian Chief. Edited by Joy Inglis. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0774803335

- Bancroft-Hunt, Norman. People of the Totem: The Indians of the Pacific Northwest. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988. ISBN 0806121459.

- Boas, Franz. Kwakiutl Tales. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1910. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- Boas, Franz. Contributions to the Ethnology of the Kwakiutl. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1977 (original 1925). ISBN 0404505538.

- Boas, Franz. The Kwakiutl of British Columbia, a Documentary by Franz Boas. Bill Holm Center, 2007 (original 1930).

- Fisher, Robin. Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1992. ISBN 0774804009.

- Goldman, Irving. The Mouth of Heaven: an Introduction to Kwakiutl Religious Thought. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, 1975. ISBN 0471311405.

- Hawthorn, Audrey. Kwakiutl Art. University of Washington Press, 1988. ISBN 0295966408.

- Jonaitis, Aldona. From the Land of the Totem Poles. University of Washington Press, 1991. ISBN 0295970227.

- Jonaitis, Aldona (ed.). Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch. Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre, 1996. ISBN 1550544802.

- Masco, Joseph. "It Is a Strict Law That Bids Us Dance:" Cosmologies, Colonialism, Death, and Ritual Authority in the Kwakwaka'wakw Potlatch, 1849 to 1922. Comparative Studies in Society and History 37(1) (1995): 41. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- McDowell, Jim. Hamatsa: The Enigma of Cannibalism on the Pacific Northwest Coast. Ronsdale Press, 1997. ISBN 0921870477.

- Padfield, Martha. Cannibal Dances in the Kwakiutl World. Canadian Journal for Traditional Music (1991). Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- Reid, Martine, and Daisy Sewid-Smith. Paddling to Where I Stand. University of Washington Press, 2004. ISBN 029598435X.

- Rohner, Ronald, and Evelyn Bettauer. The Kwakiutl Indians of British Columbia. Waveland Press, 1986. ISBN 0881332259.

- Schultz, Jeffrey D. Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics. Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 1573561487.

- Sewid, James P. Guests Never Leave Hungry: The Autobiography of James Sewid, a Kwakiutl Indian. Edited by James P. Spradley. New Haven, CT: Yale University, 1969. ISBN 978-0300010756

- Turner, Victor. The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University. 1969. ISBN 0801404320.

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744.

- Walens, Stanley. “Review of the Mouth of Heaven by Irving Goldman,” American Anthropologist. 1981.

- Wallas, Chief James. Kwakiutl Legends. Hancock House Publishing, 1989. ISBN 0888392303.

External links

All links retrieved June 13, 2018.

- U'mista Cultural Society

- Kwakiutl Language (Kwak'wala, Kwakwaka'wakw)

- Kwakiutl Indian Culture and History

- Kwakiutl Masks

- Kwakwaka'wakw First Nations Land Rights and Environmentalism in British Columbia

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Kwakiutl history

- Kwakwaka'wakw history

- Hamatsa history

- Kwak'wala history

- Kwakwaka'wakw_mythology history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.