Kundalini

Kundalini (from Sanskrit कुण्डलिनी meaning "coiled") refers to a system of Indian yoga, which aims to awaken and harness the intrinsic energy force found within each person for the purpose of spiritual enlightenment. This energy force, called Shakti, can be envisioned either as a goddess or as a sleeping serpent coiled at the base of the spine.[1][2] As a goddess, Shakti seeks to unite herself with the Supreme Being (Lord Shiva), where the aspirant becomes engrossed in deep meditation and infinite bliss.[3][4]

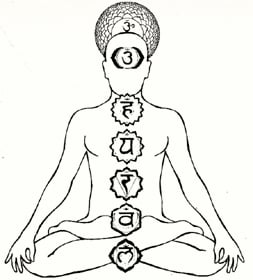

The purpose of Kundalini Yoga is to awaken the energy that resides in the spine by activating the nerve channels that are intertwined there. It links movement with breath and focuses on moving energy through the chakra system, stimulating the energy in the lower chakras and moving it to the higher chakras. The chakras are energy centers, seven in total, located beginning at the base of the spine and ending at the top of the head. Activation of the subtle body is enabled along the chakras (energy centres) and nadis (channels). Both Kundalini Yoga and Tantra propose that this energy may be "awakened" by such means as austerities, breath and other physical exercises, visualization and chanting. It may then rise up a subtle channel at the spine (called Sushumna) to the head, bringing psychological illumination. Each chakra is said to contain special characteristics.[5] Kundalini Yoga has many points in common with Chinese acupuncture.

Yoga

Kundalini yoga is a physical and meditative discipline, comprising a set of techniques that use the mind, senses and body to create a communication between "mind" and "body." Kundalini yoga focuses on psycho-spiritual growth and the body's potential for maturation, giving special consideration to the role of the spine and the endocrine system in the understanding of yogic awakening.[6]

Kundalini is a concentrated form of prana or life force, lying dormant in chakras in the body. It is conceptualized as a coiled up serpent (literally, 'kundalini' in Sanskrit is 'That which is coiled'). The serpent is considered to be female, coiled up two and a half times, with its mouth engulfing the base of the Sushumna nadi.

Kundalini yoga is sometimes called "the yoga of awareness" because it awakens the "kundalini" which is the unlimited potential that already exists within every human being.[7] Practitioners believe that when the infinite potential energy is raised in the body it stimulates the higher centers, giving the individual enhanced intuition and mental clarity and creative potential. As such, kundalini was considered a dangerous practice by ruling powers and so, was historically practiced in secret. Only after a lengthy initiation process was the knowledge handed down from Master to student.

Practice

The purpose of Kundalini Yoga is to awaken the energy that resides in the spine by activating the nerve channels that are intertwined there. It links movement with breath and focuses on moving energy through the chakra system, stimulating the energy in the lower chakras and moving it to the higher chakras. The chakras are energy centers, seven in total, located beginning at the base of the spine and ending at the top of the head.

The practice of kundalini yoga consists of a number of bodily postures, expressive movements and utterances, cultivation of character, breathing patterns, and degrees of concentration.[6] None of these postures and movements should, according to scholars of Yoga, be considered mere stretching exercises or gymnastic exercises. Many techniques include the following features: cross-legged positions, the positioning of the spine (usually straight), different methods to control the breath, the use of mantras, closed eyes, and mental focus (often on the sound of the breath).

In the classical literature of Kashmir Shaivism, kundalini is described in three different manifestations. The first of these is as the universal energy or para-kundalini. The second of these is as the energizing function of the body-mind complex or prana-kundalini. The third of these is as consciousness or shakti-kundalini which simultaneously subsumes and intermediates between these two. Ultimately these three forms are the same but understanding these three different forms will help to understand the different manifestations of kundalini.[8]

Indian Sources

A number of models of this esoteric subtle anatomy occur in the class of texts known as Āgamas or Tantras, a large body of scriptures, rejected by many orthodox Brahmins.[9] In early the texts, there were various systems of chakras and nadis, with varying connections between them. Over time a system of six or seven chakras up the spine was adopted by most schools. This particular system, which may have originated in about the eleventh century C.E., rapidly became widely popular.[10] This is the conventional arrangement, cited by Monier-Williams, where the chakras are defined as "6 in number, one above the other".[11]

The most famous of the Yoga Upanishads, the Yogatattva, mentions four kinds of yoga, one of which, laya-yoga, involves Kundalini.[12] Another source text for the concept is the Hatha Yoga Pradipika written by Swami Svatmarama (English translation, 1992) somewhere between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries.[13]

Western interpretation

Sir John Woodroffe (pen name Arthur Avalon) was one of the first to bring the notion of Kundalini to the West. A High Court Judge in Calcutta, he became interested in Shaktism and Hindu Tantra. His translation of and commentary on two key texts was published as The Serpent Power. Woodroffe rendered Kundalini as "Serpent Power."

Western awareness of the idea of Kundalini was strengthened by the Theosophical Society and the interest of the psychoanalyst Carl Jung (1875-1961)[14] "Jung's seminar on Kundalini yoga, presented to the Psychological Club in Zurich in 1932, has been widely regarded as a milestone in the psychological understanding of Eastern thought. Kundalini yoga offered Jung a model for the development of higher consciousness, and he interpreted its symbols in terms of the process of individuation".[15]

In the early 1930s two Italian scholars, Tommaso Palamidessi and Julius Evola, published several books with the intent of re-interpreting alchemy with reference to yoga.[16] Those works had an impact on modern interpretations of Alchemy as a mystical science. In those works, Kundalini was called an Igneous Power or Serpentine Fire.

Another popularizer of the concept of Kundalini among Western readers was Gopi Krishna. His autobiography is entitled Kundalini—The Evolutionary Energy in Man.[17] According to June McDaniel, Gopi Krishna's writings have influenced Western interest in kundalini yoga.[18] Swami Sivananda produced an English language manual of Kundalini Yoga methods. Other well-known spiritual teachers who have made use of the idea of kundalini include Osho, George Gurdjieff, Paramahansa Yogananda, Swami Rudrananda Yogi Bhajan and Nirmala Srivastava.

Kundalini references may commonly be found at present in a wide variety of derivative "New Age" presentations. Stuart Sovatsky warns that the popularization of the term within New Religious Movements has not always contributed to a mature understanding of the concept.[19]

Recently, there has been a growing interest within the medical community to study the physiological effects of meditation, and some of these studies have applied the discipline of Kundalini Yoga to their clinical settings.[20][21] Their findings are not all positive. Researchers in the fields of Humanistic psychology,[22] Transpersonal psychology,[23] and Near-death studies[24] describe a complex pattern of sensory, motor, mental and affective symptoms associated with the concept of Kundalini, sometimes called the Kundalini Syndrome.[25]

Lukoff, Lu & Turner[26] notes that a number of psychological difficulties might be associated with Asian spiritual practices, and that Asian traditions recognize a number of pitfalls associated with intensive meditation practice. Transpersonal literature[27] also notes that kundalini practice is not without dangers. Anxiety, dissociation, depersonalization, altered perceptions, agitation, and muscular tension have been observed in western meditation practitioners[28] and psychological literature is now addressing the occurrence of meditation-related problems in Western contemplative life.[29][30]

Some modern experimental research [31] seeks to establish links between Kundalini practice and the ideas of Wilhelm Reich and his followers.

Notes

- ↑ Gavin Flood. An Introduction to Hinduism. (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1996), 99.

- ↑ June McDaniel. Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal. (Oxford University Press, 2004), 103

- ↑ "The Blessing Of Life: Awakening of Kundalini." Kundalini Yogasiddhashram.org. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Kundalini Yoga from Swami Sivanandha.experiencefestival.com. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Bruce Scotton. "The phenomenology and treatment of kundalini." 261-270. in Chinen, Scotton and Battista, Eds. Textbook of transpersonal psychiatry and psychology. (New York, NY: Basic Books, Inc., 1996), 261-262.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Stuart Sovatsky. Words from the Soul: Time, East/West Spirituality, and Psychotherapeutic Narrative. (State University of New York Press, 1998)

- ↑ Sat Bachan Kaur Karla Becker, 2004

- ↑ Kurt Keutzer, 1996 Kundalini Yogas FAQ Electrical Engineering & Computer, Berkeley.edu. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Flood, 1996, 122.

- ↑ Flood, 1996, 99.

- ↑ Monier Monier-Williams. A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. (Delhi: Motilal-Banardidass), 380. online, [1] ibiblio.org. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ↑ Flood, 1996, 96.

- ↑ Swami Svatmarama. Hatha Yoga Pradipika. (London: The Aquarian Press, (1992). An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers. Translated by Elsy Becherer, foreword by B K S Iyengar, commentary by Hans Ulrich Rieker, 2002. ISBN 0971646619)

- ↑ John Henshaw, Knowledge of Reality magazine online Karl Jung and the Kundalini sol.com. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Carl Jung, and Sonu Shamdasani. The Psychology of Kundalini Yoga. (Princeton University Press, 1999), publisher's description

- ↑ Tommaso Palamidessi. Alchimia come via allo Spirito. (Turin: ed. EGO, 1948)

- ↑ Gopi Krishna. Kundalini: the evolutionary energy in man. (Boulder, CO: Shambhala, 1971)

- ↑ McDaniel, 280. For quotation: "Western interest at the popular level in kundalini yoga was probably most influenced by the writings of Gopi Krishna, in which kundalini was redefined as chaotic and spontaneous religious experience."

- ↑ Sovatsky, 161

- ↑ Sara W. Lazar, George Bush, Randy L. Gollub, Gregory L. Fricchione, Gurucharan Khalsa, Herbert Benson, (2000) Functional brain mapping of the relaxation response and meditation [Autonomic Nervous System] NeuroReport: Volume 11(7) 15 May 2000 p 1581–1585 PubMed Abstract PMID 10841380

- ↑ William J. Cromie. "Research: Meditation changes temperatures: Mind controls body in extreme experiments." (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University) Gazette, April 18, 2002

- ↑ David Lukoff, Francis G. Lu, & Robert P. Turner, "From Spiritual Emergency to Spiritual Problem: The Transpersonal Roots of the New DSM-IV Category." Journal of Humanistic Psychology 38(2) (1998): 21-50. online [2]spiritualcompetency.com. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ↑ Scotton, 1996

- ↑ Yvonne Kason. Farther Shores: Exploring How Near-Death, Kundalini and Mystical Experiences Can Transform Ordinary Lives. (Toronto: Harper Collins Publishers, Revised ed, 2000)

- ↑ Bruce Greyson. "Some Neuropsychological Correlates Of The Physio-Kundalini Syndrome." The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 32(2)(2000)

- ↑ Lukoff, et al., 1998

- ↑ Stanislav Grof & Christina Grof, (eds.) Spiritual Emergency: When Personal Transformation Becomes a Crisis. (New Consciousness Reader). (Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher, 1989), 15

- ↑ Lukoff, et al., 1998

- ↑ Lukoff et al., 1998

- ↑ Alberto Perez-De-Albeniz & Jeremy Holmes, "Meditation: Concepts, Effects And Uses In Therapy." International Journal of Psychotherapy 5 (1) (March 2000): 49, 10p

- ↑ Rudra. Kundalini. (Worpswede, Germany: Wild Dragon Connections, 1993)(in German)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arambula, P., Peper E, Kawakami M, Gibney KH. "The Physiological Correlates of Kundalini Yoga Meditation: A Study of a Yoga Master," Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 26(2) (Jun 2001): 147-153, PubMed Abstract PMID 11480165.

- Cromie, William J. "Research: Meditation changes temperatures: Mind controls body in extreme experiments." (Cambridge, MA) Harvard University Gazette, April 18, 2002

- Flood, Gavin. An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0521438780

- Greyson, Bruce. "Some Neuropsychological Correlates Of The Physio-Kundalini Syndrome." The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 32(2) (2000)

- Grof, Stanislav & Christina Grof, eds. Spiritual Emergency: When Personal Transformation Becomes a Crisis (New Consciousness Reader) Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher, 1989.

- Grof, Stanislav & Christina Grof. The Stormy Search for the Self. New York: Perigee Books, 1992. ISBN 087477649X

- Harper, Katherine Anne, and Robert L. Brown. The Roots of Tantra Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2002 ISBN 0791453065

- Henshaw, John, Knowledge of Reality magazine online Karl Jung and the Kundalini sol.com. Retrieved October 20, 2008

- Jung, C. G., and Sonu Shamdasani. The Psychology of Kundalini Yoga. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 0691006768.

- Kason, Yvonne. Farther Shores: Exploring How Near-Death, Kundalini and Mystical Experiences Can Transform Ordinary Lives. Toronto: Harper Collins Publishers, Revised edition, 2000. ISBN 0006386245

- Kieffer, Gene. Kundalini for the New Age - Selected Writings of Gopi Krishna. St. Paul: Paragon House, (1988) 1996. ISBN 155778745X

- Krishna, Gopi. Kundalini: the evolutionary energy in man. Boulder, CO: Shambhala, (original 1971) 1997. ISBN 1570622809.

- Lukoff, David, Francis G. Lu, & Robert P. Turner, "From Spiritual Emergency to Spiritual Problem: The Transpersonal Roots of the New DSM-IV Category." Journal of Humanistic Psychology 38(2) (1998): 21-50. online [3].spiritualcompetency.com. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- McDaniel, June. Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal. Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0195167902

- Monier-Williams, Monier. A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal-Banardidass.

- Narayanananda, Swami. (1950) The Primal Power in Man or the Kundalini Shakti, 6th rev. ed. Denmark: N.U. Yoga Trust, 1979. ISBN 8787571609

- Palamidessi, Tommaso, ed. Alchimia come via allo spirito. Turin, Italy: ed. EGO, Arkeios (1948) 2001. ISBN 8886495501.

- Perez-De-Albeniz, Alberto, & Jeremy Holmes, "Meditation: Concepts, Effects And Uses In Therapy." International Journal of Psychotherapy 5 (1) (March 2000): 49, 10p.

- Rudra. Kundalini die Energie der Natur die Natur der Energie im Menschen. Worpswede, Germany: Wild Dragon Connections, 1993. ISBN 3980256014

- Scotton, Bruce. "The phenomenology and treatment of kundalini." 261-270. in Chinen, Scotton and Battista, Eds. Textbook of transpersonal psychiatry and psychology. New York, NY: Basic Books, Inc., 1996.

- Sannella, Lee. The Kundalini Experience. CA: Integral Publishing, 1987. ISBN 0941255299

- Selig, Zachary and Jon Selby. Kundalini Awakening, a Gentle Guide to Chakra Activation and Spiritual Growth. New York: Random House, 1992. ISBN 0553353306

- Sovatsky, Stuart. Words from the Soul: Time, East/West Spirituality, and Psychotherapeutic Narrative. State University of New York Press, 1998. ISBN 079143950X (Suny Series in Transpersonal and Humanistic Psychology)

- Svatmarama, Swami. Hatha Yoga Pradipika. London: The Aquarian Press, (1992). An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers. Translated by Elsy Becherer, foreword by B K S Iyengar, commentary by Hans Ulrich Rieker 2002. ISBN 0971646619.

- Tweedie, I., Daughter of Fire: A Diary of a Spiritual Training with a Sufi Master. The Golden Sufi Center, 1995. ISBN 0963457454.

- White, J. ed. Kundalini. Evolution and enlightenment. New York: Paragon House, 1990.

- Woodroffe, Sir John/Arthur Avalon. The Serpent Power. reprint ed. Ganesh & Co., 2003. ISBN 8185988056.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.