Khmer Empire

| This article is part of the History of Cambodia series |

|---|

|

| Early history of Cambodia |

| Migration of Kambojas |

| Funan (AD1 - AD630) |

| Chenla (AD630 - AD802) |

| Khmer Empire (AD802 - AD1432) |

| Rule over Isan |

| Dark ages of Cambodia (1432 - 1863) |

| Loss of Mekong Delta to Việt Nam |

| Colonial Cambodia (1863-1954) |

| Post-Independence Cambodia |

| Cambodian Civil War (1967-1975) |

| Coup of 1970 |

| Việt Nam War Incursion of 1970 |

| Khmer Rouge Regime (1975-1979) |

| Việt Nam-Khmer Rouge War (1975-1989) |

| Vietnamese Occupation (1979-1990) |

| Modern Cambodia (1990-present) |

| 1991 UNAMIC |

| 1992-93 UNTAC |

| Timeline |

| [edit this box] |

The Khmer empire was the largest continuous empire of South East Asia, based in what is now Cambodia. The empire, which seceded from the kingdom of Chenla around 800 C.E., at times ruled over or vassalized parts of modern-day Laos, Thailand and Vietnam. During its formation, the Khmer Empire had intensive cultural, political, and trade relations with Java, and later with the Srivijaya empire that lay beyond the Khmer state's southern border. After Thai invaders (Siamese) conquered Angkor in 1431, the Khmer capital moved to Phnom Penh, which became an important trade center on the Mekong River. Costly construction projects and conflicts within the royal family sealed the end of the Khmer empire during the seventeenth century.

No written historical documentation of the Khmer Empire remains; knowledge of the Khmer civilization is derived primarily from stone inscriptions in many languages including Sanskrit, Pali, Birman, Japanese, and even Arabic, at archaeological sites and from the reports of Chinese diplomats and traders. Its greatest legacy is Angkor, which was the capital during the empire's zenith. Angkor bears testimony to the Khmer empire's immense power and wealth, and the variety of belief systems that it patronized over time. The empire's official religions included Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism, until Theravada Buddhism prevailed after its introduction from Sri Lanka in the thirteenth century. Satellite imaging reveals Angkor to have been the largest pre-industrial urban center in the world, larger than modern-day New York.

History

The history of Angkor, as the central area of settlement in the historical kingdom of Kambuja, is also the history of the Khmer people from the ninth to the fifteenth centuries. No written records have survived from Kambuja or the Angkor region, so current historical knowledge of the Khmer civilization is derived primarily from :

- archaeological excavation, reconstruction and investigation

- inscriptions on stela and on stones in the temples, which report on the political and religious deeds of the kings

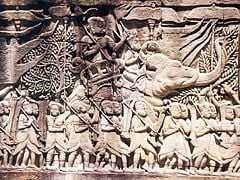

- reliefs in a series of temple walls with depictions of military marches, life in the palace, market scenes and the everyday lives of the population

- reports and chronicles of Chinese diplomats, traders and travelers.

Jayavarman II - the founder of Khmer Empire

The era of the Khmer kingdom of Angkor started around 800 C.E., when King Jayavarman II married into a local ruling family of that place. Jayavarman II (reigned 802 to 850 C.E.), lived as a prince at the court of Sailendra dynasty in Java (Indonesia), either as a hostage or in order to receive an education there. He was probably influenced by the refined art and culture of Javan Sailendra, including the concept of the divine Dewa-Raja (God-King) which was prominent during the Sailendra dynasty. In 802, he returned to Cambodia, declared himself the "universal monarch" (chakravartin), God-King (devaraja) Jayavarman II, [1][2]and declared the independence of Kambujadesa (Cambodia) from Java. Records of this declaration have given rise to speculation that Cambodia, a group of politically independent principalities collectively known to the Chinese as Chenla,[3][4] might have been the dependent vassal of Java for some years before the reign of Jayavarman II.

Jayavarman II established his capital of Hariharalaya (now known as "Roluos") at the northern end of Tonle Sap. Through a program of military campaigns, alliances, marriages and land grants, he achieved a unification of the country bordered by China (to the north), Champa (to the east), the ocean (to the south) and a place identified by a stone inscription as "the land of cardamoms and mangoes" (to the west).

There is speculation that Jayavarman II was probably linked to a legendary king called Jayavarman Ibis, known from the inscriptions K. 103 (dated April 20, 770) and K. 134 (dated 781), who settled in the Angkor region and married into a local ruling family, as corroborated by the inscriptions of Preah Ko (K. 713, dated Monday, January 25, 880), Bakong (K. 826, dated 881/82) and Lolei (K. 324, dated Sunday, July 8, 893). All other information about this king, including the date of his accession, is late and legendary, taken mainly from the Sdok Kak Thom inscription (K. 235, dated February 8, 1053.

Yasodharapura - the First City of Khmer Empire

Jayavarman II's first three successors are also only known from the inscriptions. Indravarman I (reigned 877 – 889) expanded the kingdom without waging wars, and began extensive building projects, using wealth gained through trade and agriculture. Foremost among these were the temple of Preah Ko, dedicated on Monday, January 25, 880 and irrigation works.

In 889 C.E.., Yasovarman I ascended to the throne.[5] A great king and an accomplished builder, he was celebrated by one inscription as "a lion-man; he tore the enemy with the claws of his grandeur; his teeth were his policies; his eyes were the Veda."[6] Near the old capital of Hariharalaya, Yasovarman constructed a new city called Yasodharapura. In the tradition of his predecessors, he also constructed a massive reservoir called the East Baray, a massive water reservoir measuring roughly 7.5 by 1.8 kilometers.

The city's central temple was built on Phnom Bakheng (Sanskrit: Hemadri), a hill which rises around 60 meters above the plain on which Angkor sits, and surrounded by a moat fed from the baray. He also built numerous other Hindu temples and ashramas, or retreats for ascetics.[7]

At the beginning of the tenth century the kingdom split, and Jayavarman IV established a new capital at Koh Ker, some 100 km northeast of Angkor. Rajendravarman II (reigned 944 - 968) returned the royal palace to Yasodharapura. He resumed the extensive building schemes of the earlier kings and established a series of temples in the Angkor area, including Pre Rup and the East Mebon, on an island in the middle of the East Baray (dedicated on the January 28, 953), and several Buddhist temples and monasteries. In 950, the first war took place between Kambuja and the kingdom of Champa to the east (in the modern central Vietnam).

The son of Rajendravarman II, Jayavarman V, reigned from 968 to c. 1001. After he had established himself as the new king over the other princes, his rule was a largely peaceful period, marked by prosperity and cultural flowering. He established a new capital near Yashodharapura, Jayenanagari. Philosophers, scholars and artists resided at the court of Jayavarman V. New temples were also established: the most important of these are Banteay Srei, considered one of the most beautiful and artistic of Angkor, and Ta Keo, the first temple of Angkor built completely of sandstone.

A decade of conflict followed the death of Jayavarman V. A series of kings reigned only for a few years, and were each violently replaced by his successor, until Suryavarman I (reigned 1002 - 1049) gained the throne after a long war against his rival king Jayaviravarman (r. 1002 - c. 1017). His rule was marked by repeated attempts by his opponents to overthrow him and by military conquests. In the west he extended the kingdom to the modern city of Lopburi in Thailand, in the south to the Kra Isthmus. Under Suryavarman I, construction of the West Baray, the second and even larger {8 by 2.2 km) water reservoir after the Eastern Baray, began.

Between 900 and 1200 C.E., the Khmer Empire produced some of the world's most magnificent architectural masterpieces in Angkor. In 2007 an international team of researchers using satellite photographs and other modern techniques concluded that the medieval settlement around the temple complex Angkor had been the largest preindustrial city in the world with an urban sprawl of 1,150 square miles. The closest rival to Angkor, the Mayan city of Tikal in Guatemala, was roughly 50 square miles in total size.[8]

Suryavarman II

The eleventh century was a period of conflict and brutal power struggles. For a few decades, under Suryavarman II (reigned 1113 - after 1145) the kingdom was united internally and able to expand. Suryavarman ascended to the throne after prevailing in a battle with a rival prince. An inscription says that in the course of combat, Suryavarman lept onto his rival's war elephant and killed him, just as the mythical bird-man Garuda slays a serpent.[9]

Suryavarman II conquered the Mon kingdom of Haripunjaya to the west (in today's central Thailand), and the area further west to the border with the kingdom of Bagan (modern Burma); in the south he took further parts of the Malay peninsula down to the kingdom of Grahi (corresponding roughly to the modern Thai province of Nakhon Si Thammarat; in the east, several provinces of Champa; and the countries in the north as far as the southern border of modern Laos. The last inscription, which mentions Suryavarman II's name in connection with a planned invasion of Vietnam, is dated Wednesday, October 17, 1145. He probably died during a military expedition between 1145 and 1150, an event which weakened the kingdom considerably.

Another period of disturbances, in which kings reigned briefly and were violently overthrown by rebellions or wars, followed the death of Suryavarman II. Kambuja’s neighbors to the east, the Cham of what is now southern Vietnam, took launched a seaborne invasion in 1177 up the Mekong River and across Tonle Sap. The Cham forces sacked the Khmer capital of Yasodharapura and killed the reigning king, incorporating Kambuja as a province of Champa.

Jayavarman VII - Angkor Thom

Following the death of Suryavarman around 1150 C.E., the kingdom fell into a period of internal strife. However, a Khmer prince who was to become King Jayavarman VII rallied his people and defeated the Cham in battles on the lake and on the land. In 1181, Jayavarman assumed the throne. He was to be the greatest of the Angkorian kings.[10] Over the ruins of Yasodharapura, Jayavarman constructed the walled city of Angkor Thom, as well as its geographic and spiritual center, the temple known as the Bayon. Bas-reliefs at the Bayon depict not only the king's battles with the Cham, but also scenes from the life of Khmer villagers and courtiers. In addition, Jayavarman constructed the well-known temples of Ta Prohm and Preah Khan, dedicating them to his parents. This massive program of construction coincided with a transition in the state religion from Hinduism to Mahayana Buddhism, since Jayavarman himself had adopted the latter as his personal faith. During Jayavarman's reign, Hindu temples were altered to display images of the Buddha, and Angkor Wat briefly became a Buddhist shrine. Following his death, a Hindu revival included a large-scale campaign of desecrating Buddhist images, until Theravada Buddhism became established as the land's dominant religion from the fourteenth century.[11]

The future king Jayavarman VII (reigned 1181-after 1206) had already been a military leader as a prince under previous kings. After the Cham had conquered Angkor, he gathered an army and reclaimed the capital, Yasodharapura. In 1181 he ascended the throne and continued the war against the neighboring eastern kingdom for 22 years, until the Khmer defeated Champa in 1203 and conquered large parts of its territory.

Jayavarman VII is regarded as the last of the great kings of Angkor, not only because of the successful war against the Cham, but because he was not a tyrant like his immediate predecessors, unified the empire, and carried out a number of building projects during his rule. Over the ruins of Yasodharapura, Jayavarman constructed the walled city of Angkor Thom, as well as its geographic and spiritual center, the temple known as the Bayon. Bas-reliefs at the Bayon depict not only the king's battles with the Cham, but also scenes from the life of Khmer villagers and courtiers. Its towers, each several meters high and carved out of stone, bear faces which are often wrongly were identified as those of the boddhisattva Lokeshvara (Avalokiteshvara). In addition, Jayavarman constructed the well-known temples of Ta Prohm and Preah Khan, dedicating them to his parents, and the reservoir of Srah Srang. This massive program of construction coincided with a transition in the state religion from Hinduism to Mahayana Buddhism, which Jayavarman had adopted as his personal faith. During Jayavarman VII's reign, Hindu temples were altered to display images of the Buddha, and Angkor Wat briefly became a Buddhist shrine. An extensive network of roads was laid down, connecting every town of the empire. Beside these roads, 121 rest-houses were built for traders, officials and travelers, and 102 hospitals were established.

Zhou Daguan - the Last Blooming

The history of the kingdom after Jayavarman VII is unclear. In the year 1220 the Khmer withdrew from many of the provinces they had previously taken from Champa. One of the successors of Jayavarman VII, Indravarman II, died in 1243. In the west, his Thai subjects rebelled, established the first Thai kingdom at Sukhothai and pushed back the Khmer. During the next two centuries, the Thai became the chief rivals of Kambuja. Indravarman II was probably succeeded by Jayavarman VIII (reigned 1243 or 1267 - 1295).

During the thirteenth century most of the statues of Buddha statues in the empire (archaeologists estimate the number at over 10,000, of which few traces remain) were destroyed, and Buddhist temples were converted to Hindu temples. During the same period the construction of the Angkor Wat probably took place, sponsored by a king known only by his posthumous name, Paramavishnuloka. From the outside, the empire was threatened in 1283 by the Mongols under Kublai Khan's general Sagatu. The king avoided war with his powerful opponent, who at that time ruled over all China, by paying annual tribute to him. Jayavarman VIII's rule ended in 1295 when he was deposed by his son-in-law Srindravarman (reigned 1295-1308). The new king was a follower of Theravada Buddhism, a school of Buddhism which had arrived in southeast Asia from Sri Lanka and subsequently spread through most of the region.

In August of 1296, the Chinese diplomat representing Yuan] Emperor Chengzong Zhou Daguan arrived at Angkor, and remained at the court of King Srindravarman until July 1297. He was neither the first nor the last Chinese representative to visit Kambuja, but his stay was notable because he later wrote a detailed report on life in Angkor, which is one of the most important sources of information about historical Angkor. His descriptions of several great temples (the Bayon, the Baphuon, Angkor Wat), contain the information that the towers of the Bayon were once covered in gold), and the text also offers valuable information on the everyday life and the habits of the inhabitants of Angkor.

Zhou Daguan found what he took to be three separate religious groups in Angkor. The dominant religion was that of Theravada Buddhism. Zhou observed that the monks had shaven heads and wore yellow robes.[12] The Buddhist temples impressed Zhou with their simplicity; he noted that the images of Buddha were made of gilded plaster.[13] The other two groups identified by Zhou appear to have been those of the Brahmans and of the Shaivites (lingam worshipers). About the Brahmans Zhou had little to say, except that they were often employed as high officials. [14] Of the Shaivites, whom he called "Taoists," Zhou wrote, "the only image which they revere is a block of stone analogous to the stone found in shrines of the god of the soil in China."[15]

Decline and the End of the Angkorean Empire

There are few historical records from the time following Srindravarman's reign. An inscription on a pillar mentions the accession of a king in the year 1327 or 1267. No further large temples were established. Historians suspect a connection with the kings' adoption of Theravada Buddhism, which did not require the construction of elaborate temples to the gods. The western neighbor of the Empire, the first Thai kingdom of Sukhothai, was conquered by another Thai kingdom, Ayutthaya, in 1350. After 1352 several assaults on Kambuja were repelled. In 1431, however, the superiority of Ayutthaya was too great, and, according the [[Thailand}Thai]] chronicles, the Thai army conquered Angkor.

The center of the residual Khmer kingdom was in the south, in the region of today's Phnom Penh. However, there are indications that Angkor was not completely abandoned, including evidence for the continued use of Angkor Wat. King Ang Chand (reigned 1530-1566) ordered the covering of two hitherto unfilled galleries of that temple with scenes from the Ramayana. Under the rule of king Barom Reachea I (reigned 1566 - 1576), who temporarily succeeded in driving back the Thai, the royal court was briefly returned to Angkor. From the seventeenth century there are inscriptions which testify to Japanese settlements alongside those of the remaining Khmer. The best-known relates that Ukondafu Kazufusa celebrated the Khmer New Year there in 1632.

One line of Khmer kings probably remained in Angkor, while a second moved to Phnom Penh to establish a parallel kingdom. The final fall of Angkor would then have been due to the transfer of economic, and therefore political, significance, as Phnom Penh became an important trade centre on the Mekong River. Costly construction projects and conflicts within the royal family sealed the end of the Khmer empire.

Water Reservoirs

The nature and importance of the massive water reservoirs or baray surrounding the temples at Angkor has been a subject of debate among scholars for decades. Some believe that the baray were used to secure a steady supply of water to irrigate rice fields, making them central to the Angkorean economy and essential to sustaining the population of Angkor. An elaborate system of canals connecting to the reservoirs was used for trade, travel and irrigation. They theorize that Angkor’s expanding population put increased strain on the water system and caused seasonal flooding and water shortages. Forests were cut down in the Kulen hills to make room for more rice fields, and runoff from the rains began to carry sediment into the canal system. When the baray became full of silt due to poor maintenance, the population at Angkor could no longer be sustained, eventually leading to the abandonment of the temple site at Angkor in favor of Phnom Penh, and the consequent decline of the Angkorean Empire. This theory is known as the hydraulic paradigm.

However, recent research by W. J. Van Liere and Robert Acker suggests that the baray could not have been used for large scale irrigation. Some researchers, including Milton Osborne, have suggested that the baray may have been symbolic in nature, representing the ocean surrounding Mount Meru and fulfilling the Hindu mythological cosmos, which the Khmer God Kings attempted to recreate on earth as a sign of their relationship with the Hindu gods. Research efforts, such as the Greater Angkor Project, of the University of Sydney, are still being conducted to confirm or reject the hydraulic paradigm.[16].[17]

Timeline of rulers

Chronological listing with reign, title and posthumous title(s), where known.

- 657-681: Jayavarman I

- c.700-c.713: Jayadevi

- 770 and 781 Jayavarman Ibis, probably identical with Jayavarman II

- 9th century: Jayavarman II (Parameshvara)

- 9th century: Jayavarman III (Vishnuloka)

- 9th century: Rudravarman (Rudreshvara)

- 9th century-877: Prthivindravarman (Prthivindreshvara)

- 877-889: Indravarman I (Isvaraloka)

- 889-910: Yasovarman I (Paramasivaloka)

- 910-923: Harshavarman I (Rudraloka)

- 923-928: Isānavarman II (Paramarudraloka)

- 921-941: Jayavarman IV (Paramasivapada)

- 941-944: Harshavarman II (Vrahmaloka or Brahmaloka)

- 944-968: Rājendravarman (Sivaloka)

- 968-1001: Jayavarman V (Paramasivaloka)

- 1001-1002?: Udayādityavarman I

- 1002-1017?: Jayaviravarman

- 1001-1049: Suryavarman I (Nirvanapada)

- 1049-1067: Udayādityavarman II

- 1066-1080?: Harshavarman III (Sadasivapada)

- 1080-1113?: Jayavarman VI (Paramakaivalyapada)

- 1107-1112/13: Dharanindravarman I (Paramanishkalapada)

- 1113-1150: Suryavarman II (not known)

- 1160-1165/6: Yasovarman II

- 1166-1177: Tribhuvanāditya (Mahāparamanirvanapada)

- 1181-1206?: Jayavarman VII (Mahāparamasaugata?)

- 13th century-1243: Indravarman II

- 13th century: not known (Paramavisnuloka)

- 1243 or 1267-1295: Jayavarman VIII (abdicated) (Paramesvarapada)

- 1295-1308: Srindravarman

- 1308-1327?: Indrajayavarman

Notes

- ↑ Charles Higham. The Civilization of Angkor. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 53 ff.

- ↑ David P. Chandler. A History of Cambodia. (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1983), 34 ff.

- ↑ Chandler. A History of Cambodia. 26

- ↑ G. Coedès. Pour mieux comprendre Angkor. (Hanoi: Imprimerie D'Extreme-Orient, 1943), 4.

- ↑ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, 63 ff.

- ↑ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, 40.

- ↑ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor,60; Chandler, A History of Cambodia, 38 f.

- ↑ "Map reveals ancient urban sprawl," BBC News, 14 August 2007.

- ↑ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, 112 ff.; Chandler, A History of Cambodia, 49.

- ↑ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, 120 ff.

- ↑ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, 116.

- ↑ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, 137.

- ↑ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, 72.

- ↑ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, 72.

- ↑ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, 72.

- ↑ Damian Evans, Jens-Uwe Korff & Kathryn Sund. Great Angkor Project. University of Sydney. Retrieved October 21, 2007.

- ↑ Miranda Leitsinger. Associated Press.Scientists dig and fly over Angkor in search of answers to golden city's fall, 9:15 A.M. June 13, 2004, Union-Tribune Publishing. Retrieved October 21, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bhattacharya, Kamaleswar. 1966. Les religions brahmaniques dans l’ancien Cambodge d’après l’épigraphie et l’iconographie. Paris.

- Boisselier, Jean. 1966. Le Cambodge. Paris.

- Chandler, David [Porter]. 1996. Facing the Cambodian Past: Selected Essays 1971-1994. Chiang Mai.

- Chandler, David P. 1983. A history of Cambodia. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0865315787

- Coedes, G. Pour Mieux Comprendre Angkor. Hanoi: Imprimerie D'Extreme-Orient, 1943. (French)

- Herz, Martin Florian. 1958. A short history of Cambodia from the days of Angkor to the present. New York: F.A. Praeger.

- Higham, Charles, Rachanie Thosarat, and J. Cameron. 2004. The origins of the civilization of Angkor. Bangkok: Fine Arts Department of Thailand. ISBN 9744176881

- Higham, Charles. 2001. The civilization of Angkor. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520234421

- Inscriptions du Cambodge, Éd. et trad. par George Cœdès. Vol. I-VIII. Hanoi & Paris: EFEO 1937-1966. (Collection de Textes et Documents sur l’Indochine III)

- Inscriptions sanscrites de Campā et du Cambodge. Par Abel Bergaigne et A[uguste] Barth. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale 1885-1893.

- Jacques, Claude. 1985. “The Kamrateṅ Jagat in ancient Cambodia.” Indus Valley to Mekong Delta. (Explorations in Epigraphy.) Ed. by Noboru Karashima, Madras: 269-286.

- National Geographic Society (U.S.). 1981. Splendors of the past lost cities of the ancient world. Washington, D.C.: The Society. ISBN 0870443585

- Pelliot, Paul. 1903. «Le Fou-nan», Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient, III, 248-303.

- Vickery, Michael. “Funan reviewed: Deconstructing the Ancients,” Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient, XC-XCI, 2003-2004, S. 101-143.

- Vickery, Michael. 1985. “The Reign of Sūryavarman I and Royal Factionalism at Angkor,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 16, S. 226-244.

- Vickery, Michael. 1998. Society, economic, and politics in pre-Angkorian Cambodia: The 7th-8th centuries. Tokyo. Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies for UNESCO. (limited to preAngkorian written records)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.