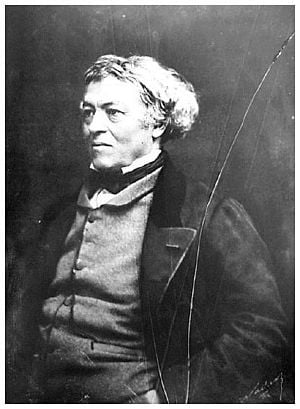

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (July 16, 1796 – February 22, 1875) was a French landscape painter and printmaker in etching.

An artist who never faced the financial troubles that countless colleagues of his time faced, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot was the leader of the Barbizon School. His art deviated from contemporaries and previous masters in that his landscape painting portrayed nature as fresh and informal. He would live a life of great prestige and wealth; however, he didn't overlook the misery of his colleagues, and was a symbol of great charity in his lifetime.

Biography

Camille Corot was born in Paris in 1796, to Louis Jacques Corot, a cloth merchant, and Marie Françoise Oberson Corot, in a house on the Quai by the rue du Bac, long since demolished. His family were members of the bourgeoisie, and unlike the experiences of some of his artistic colleagues, throughout his life he never felt the want of money. At the age of eleven, he received an education at Rouen. He was apprenticed to a draper, but hated commercial life and despised what he called its "business tricks." Nevertheless, Corot faithfully remained in the profession until he was 26, when his father finally consented to allow him to take up the profession of art.

Corot learned little from his masters. He received artistic training from both Achille Etna Michallon and Jean Victor Bertin until 1822, when he made one of his three trips to Italy. He visited Italy on three occasions, and two of his Roman studies hang in the Louvre. A regular contributor to the Salon, in 1846, the French government decorated him with the cross of the Légion d'Honneur, and he was promoted to an officer in 1867. His many friends considered, nevertheless, that he was officially neglected, and in 1874, a short time before his death, they presented him with a gold medal. He died in Paris and was buried at Père Lachaise.

A number of followers called themselves Corot's pupils. The best known are Camille Pissarro, Eugène Boudin, Berthe Morisot, Stanislas Lépine, Antoine Chintreuil, François-Louis Français, Le Roux, and Alexandre DeFaux.

During the last few years of his life he earned large sums with his pictures, which were in great demand. In 1871, he gave £2000 to the poor of Paris, under siege by the Prussians (part of the Franco-Prussian War). During the actual Paris Commune, he was at Arras with Alfred Robaut. In 1872, he bought a house in Auvers as a gift for Honoré Daumier, who by then was blind, without resources, and homeless. Finally, in 1875, he donated 10,000 francs to the widow of Jean-Francois Millet, a fellow member of the Barbizon School, in support of her children. His charity was near proverbial. He also financially supported the keep of a daycenter for children, rue Vandrezanne, in Paris.

Camille Corot never married in his lifetime, claiming that married life would interfere with his artistic aspirations. He died on February 22, 1875, in Paris, France. The works of Corot are housed in museums in France and the Netherlands, Britain, and America.

Corot on the rise

Corot was the leading painter of the Barbizon school of France in the mid-nineteenth century. As a marquee name in the area of landscape painting, his work embodied the Neo-Classical tradition and anticipated the plein-air innovations of Impressionism. Impressionist painter, Claude Monet exclaimed, "There is only one master here—Corot. We are nothing compared to him, nothing." His contributions to figure painting are hardly less important; Edgar Degas preferred his figures to his landscapes, and the classical figures of Pablo Picasso pay overt homage to Corot's influence.

The chaos of the revolution in 1830 impelled Corot to move to Chartres and paint the Chartres Cathedral, one of the most renown cathedrals worldwide. "In 1833, Corot's Ford in the Forest of Fontainebleau earned a second-class medal; although he also received this award in 1848 and 1867, the first-class medal was always denied him." Some of his major commissions and honors include his painting of a Baptism of Christ (1845) for the church of St. Nicolas du Chardonnet in Paris, and the cross of the Legion of Honor in the following year.

Historians somewhat arbitrarily divided his work into periods, but the point of division is never certain, as he often completed a picture years after he began it. In his early period he painted traditionally and "tight"—with minute exactness, clear outlines, and with absolute definition of objects throughout. After his 50th year, his methods changed to breadth of tone and an approach to poetic power, and about 20 years later, from about 1865 onwards, his manner of painting became full of enigma and poetic voice. In part, this evolution in expression can be seen as marking the transition from the plein-air paintings of his youth, shot through with warm natural light, to the studio-created landscapes of his late maturity, enveloped in uniform tones of silver. In his final 10 years, he became the "Père (Father) Corot" of Parisian artistic circles, where he was regarded with personal affection, and acknowledged as one of the five or six greatest landscape painters the world has seen, along with Hobbema, Claude Lorrain, Turner, and Constable.

Corot approached his landscapes more traditionally than is usually believed. By comparing even his late period tree-painting and arrangements to those of Claude Lorrain, such as that which hangs in the Bridgewater gallery, the similarity in methods is seen.

In addition to the landscapes, of which he painted several hundred (so popular was the late style that there exist many forgeries), Corot produced a number of prized figure pictures. While the subjects were sometimes placed in pastoral settings, these were mostly studio pieces, drawn from the live model with both specificity and subtlety. Like his landscapes, they are characterized by a contemplative lyricism. Many of them are fine compositions, and in all cases the color is remarkable for its strength and purity. Corot also executed many etchings and pencil sketches.

Landscape painting

In the modern era, Corot's work has been exhibited but has not received the notoriety of other artists. "In The Light of Italy: Corot and Early Open-Air Painting," was one of the exhibits at The Brooklyn Museum, while "Corot," was on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. These exhibits "provide a unique dialectical opportunity to appreciate the beauty, variety and significance of plein-air painting created in Italy and France in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as well as the beauty, variety and significance of the oeuvre of one of early pleinairism's major practitioners."[1] While works from different artists in various time periods were on display, Corot's landscape paintings clearly stole the show. In fact, Corot's sensitivity to light and atmospheric conditions, albeit emphasizing the same subject matter as his contemporaries, was distinctly original. Peter Galassi, a Corot scholar, said Corot's specialty "lies in the way he wedded in his oil studies the pleinairist's sensitivity to light and atmosphere with the academician's concern for formal solidity and ordered compositional structure."

Bringing nature home

While Corot was more popular and revered in his own lifetime, his work still shines with magnificence. His loyalty to plein-air, or outdoor paintings of natural scenes has made him a legend of art. In honor of his 200th birthday, Paris put on an exhibition at the Bibliotheque Nationale, showcasing 163 paintings at the Grand Palais. What has become a major problem with Corot's masterpieces in modern day is that much of them are being faked with such flawlessness and rapidity that the value of the piece has fallen drastically, as has the appreciation for the piece. In fact, one of the bizarre details from the exhibit linked Corot's work to an obsessive Corot buyer who had passed on in the early 1920s. Of the 2,414 Corot pieces the man owned, not one was an original piece, which just shows the extent to which fake Corot's have consumed the art market. Corot and his work are often considered the link between modern art (impressionism and beyond) and that of past eras, including his Barbizon contemporaries.

Influences on, influenced by

Corot's influences extend far and wide. One of them was Eugene Cuvelier, a photographer who mainly concentrated on the forests in Fontainebleau, a popular site for painters and photographers. "Eugene's technical skill was acquired from his father, Adalbert, whose strong portraits of anonymous men in rural settings are included in this show. It was Adalbert, a friend of Corot, who introduced the painter to the process of cliche-verre (literally, glass negative), in which a drawing or painting done on a glass plate was printed on photographic paper."[2] Cuvelier's photographs were certainly influenced by the work of Corot and his other Barbizon friends. "His prints shared the romance with light and atmospheric effects that was the hallmark of their painting. But in turn, his work, the cliches-verre and the prints of other photographers influenced the Barbizonites, Corot being the most prominent." After 1850, notes Van Deren Coke in his 1964 book, The Painter and the Photograph, the haziness of trees in Corot's landscapes is evident, influenced by photographic blurring that resulted from the motion of leaves during the long exposure periods required. "Both his methods of drawing and painting, as well as his range of colors, seem to be derived at least in part from photographs," Coke writes. In 1928, the art historian R.H. Wilenski noted that Corot was "the first French artist whose technique was undermined by an attempt to rival the camera's true vision."

Legacy

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot's open-air natural landscapes paved the way for the advent of impressionism. He himself said of his artistic abilities, "Never leave a trace of indecision in anything whatever."[3] In his own lifetime, he assisted his fellow contemporaries, including Honore Daumier, and was considered the ideal man of charity and kindness.

Selected works

- The Bridge at Narni (1826)

- Venise, La Piazetta (1835)

- Une Matinée (1850), private collection

- Macbeth and the Witches (1859), Wallace Collection

- Baigneuses au Bord d'un Lac (1861), private collection

- Meadow by the Swamp, National Museum of Serbia

- L'Arbre brisé (1865)

- Ville d’Avray (1867)

- Femme Lisant (1869)

- Pastorale—Souvenir d'Italie (1873), Glasgow Art Gallery

- Biblis (1875)

- Souvenir de Mortefontaine (1864), Louvre

Notes

- ↑ Paul Tabor, "Landscape painting in the time of Corot.(Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot; The Brooklyn Museum and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY)." America. 176 (1): 16(3).

- ↑ Grace Glueck, "Capturing Fontainebleau Forest's Myriad Moods," The New York Times (Nov 29, 1996).

- ↑ George Mauner, "Corot, Jean Baptiste Camille (1796-1875)," in Encyclopedia of World Biography ed. Suzanne M. Bourgoin (Detroit: Gale Research, 1998).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Clark, Kenneth. Landscape into Art. New York: Transatlantic Arts, 1981. ISBN 9780719502309.

- Mauner, George. "Corot, Jean Baptiste Camille (1796-1875)." Encyclopedia of World Biography. Ed. Suzanne M. Bourgoin. Detroit: Gale Research, 1998.

- Tabor, Paul. "Landscape painting in the time of Corot." America. 176 (1): 16(3).

- Tinterow, Gary, et al. Corot. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996. ISBN 9780300085877.

- Turner, Dianne. "Corot's luminescent landscapes." School Arts. 98 (3): 31(1).

External links

All links retrieved April 3, 2018.

- Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot at the WebMuseum.

| Romanticism | |

|---|---|

| Eighteenth century - Nineteenth century | |

| Romantic music: Beethoven - Berlioz - Brahms - Chopin - Grieg - Liszt - Puccini - Schumann - Tchaikovsky - The Five - Verdi - Wagner | |

| Romantic poetry: Blake - Burns - Byron - Coleridge - Goethe - Hölderlin - Hugo - Keats - Lamartine - Leopardi - Lermontov - Mickiewicz - Nerval - Novalis - Pushkin - Shelley - Słowacki - Wordsworth | |

| Visual art and architecture: Brullov - Constable - Corot - Delacroix - Friedrich - Géricault - Gothic Revival architecture - Goya - Hudson River school - Leutze - Nazarene movement - Palmer - Turner | |

| Romantic culture: Bohemianism - Romantic nationalism | |

| << Age of Enlightenment | Victorianism >> Realism >> |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.