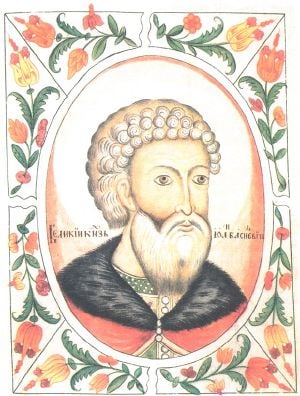

Ivan III of Russia

Ivan III Vasilevich (Иван III Васильевич) (January 22, 1440 – October 27, 1505), also known as Ivan the Great, was a grand duke of Muscovy who was the first to adopt the more pretentious title of "Grand Duke of all the Russias." Sometimes referred to as the "gatherer of the Russian lands," he quadrupled the territory of his state, claimed Moscow to be a third Rome, built the Moscow Kremlin, and laid the foundations for Russian autocracy. He remains the longest-reigning Russian ruler in history.

Background

Ivan's parents were Vasili II of Russia and Maria of Borovsk. When Ivan was five, his father was blinded during an unsuccessful coup de tat. At the age of seven, Ivan married the daughter of the Duke of Tver in exchange for help and protection. At the age of eight he joined the campaign against Khanate of Kazan to defend the Vladimir and Murom principalities. He became co-regent with his father in 1450 and succeeded him in 1462. Ivan persistently pursued the unifying policy of his predecessors. Nevertheless, he was cautious, like many of the princes of the house of Rurik. Some sources assign this to timidity, others to cold-heartedness and wisdom. Either way, he avoided any violent collision with his neighbors as much as possible until all the circumstances were exceptionally favorable. He always preferred to attain his ends gradually and indirectly. Muscovy had by this time become a compact and powerful state, while its rivals had grown weaker. This state of affairs was very favorable to the speculative activity of a statesman of Ivan III's peculiar character.

Gathering of Russian lands

Ivan’s first enterprise was a war with the republic of Novgorod, which, alarmed at the growing influence of Muscovy, had placed itself beneath the protection of Casimir IV, King of Poland. This alliance was regarded by Moscow as an act of apostasy from Orthodoxy. Although Ivan would have used any excuse to prevent nationalism from being instated, he felt heresy would be the best way to keep his supporters behind him. Ivan marched against Novgorod in 1470. No allies stood up for Novgorod. After Ivan's generals had twice defeated the forces of the republic in the summer of 1471 (by legend, ten fold outnumbered), at the rivers Shelona and Dvina, the Novgorodians were forced to ask for peace, which they obtained by agreeing to abandon forever the Polish alliance, to relinquish a considerable portion of their northern colonies, and to pay a war indemnity of 15,500 roubles.

From then on Ivan sought continually for an excuse to destroy Novgorod altogether. Although the republic allowed him to frequently violate certain ancient privileges in minor matters, the watch of the people was so astute that his opportunity to attack Novgorod did not come until 1477. In that year the ambassadors of Novgorod played into his hands by addressing him in public audience as gosudar (sovereign) instead of gospodin (sir). Ivan at once declared this statement as recognition of his sovereignty, and when the Novgorodians argued, he marched against them. Deserted by Casimir IV and surrounded on every side by the Muscovite armies, which included a Tatar contingent, the republic recognized Ivan as autocrat and surrendered on January 14, 1478, giving all prerogatives and possessions, including the whole of northern Russia from Lapland to the Urals, into Ivan’s hands.

Subsequent revolts from 1479-1488 caused Ivan to relocate en masse some of the richest and most ancient families of Novgorod to Moscow, Vyatka, and other central Russian cities. Afterward, Novgorod as an independent state ceased to exist. The rival republic of Pskov owed the continuation of its own political existence to the readiness with which it assisted Ivan against his enemy. The other principalities were virtually absorbed by conquest, purchase, or marriage contract: Yaroslavl in 1463, Rostov in 1474, and Tver in 1485.

Ivan's refusal to share his conquests with his brothers, and his subsequent interference with the internal politics of their inherited principalities, involved him in several wars with them. Though the princes were assisted by Lithuania, Ivan emerged victorious. Finally, Ivan's new inheritance policy, formally included in his last will, stated that the domains of all his kinsfolk after their deaths should pass directly to the reigning grand duke instead of reverting, as was customary, to the prince heirs, putting an end to the semi-independent princelets.

Foreign policies

It was during the reign of Ivan III that Muscovy rejected the rule of the Mongols, known as the Tatar yoke. In 1480 Ivan refused to pay the customary tribute to the Grand Akhmat Khan (Khan Ahmed). However, when the grand khan marched against him, Ivan's courage began to fail, and only the stern exhortations of the high-spirited bishop of Rostov, Vassian Patrikeyev, could induce him to take the field. All through the autumn the Russian and Tatar hosts confronted each other on opposite sides of the Ugra River, until the 11th of November, when Akhmat retired into the steppe.

In the following year, the grand khan, while preparing a second expedition against Moscow, was suddenly attacked, routed, and slain by Ivaq, the Khan of the Nogay Horde, whereupon the Golden Horde fell to pieces. In 1487 Ivan reduced the Khanate of Kazan (one of the offshoots of the Horde) to the condition of a vassal state, though in his later years it broke away from his authority. With the other Muslim powers, the Khan of the Crimean Khanate and the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire, Ivan's relations were pacific and even friendly. The Crimean Khan, Meñli I Giray, helped him against the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and facilitated the opening of diplomatic intercourse between Moscow and Istanbul, where the first Russian embassy appeared in 1495.

In Nordic affairs, Ivan III concluded an offensive alliance with Hans of Denmark and maintained a regular correspondence with Emperor Maximilian I, who called him a "brother." He built a strong citadel in Ingria (named Ivangorod after himself), which proved of great consequence to Russians in the Russo-Swedish War of 1496-1499, which had been preceded by Ivan's detention of the Hanseatic merchants trading in Novgorod.

The further extension of the Muscovite dominion was facilitated by the death of Casimir IV in 1492, when Poland and Lithuania once more parted company. The throne of Lithuania was now occupied by Casimir's son Alexander, a weak and lethargic prince. He was so incapable of defending his possessions against the persistent attacks of the Muscovites that he attempted to make peace through a matrimonial compact by marrying Helena, Ivan's daughter. However, Ivan’s clear determination to conquer as much of Lithuania as possible at last compelled Alexander to take up arms against his father-in-law in 1499. The Lithuanians were routed at Vedrosha on July 14, 1500, and in 1503 Alexander was glad to purchase peace by ceding Chernigov, Starodub, Novgorod-Seversky, and 16 other towns to Ivan.

Internal policies

The character of the government of Muscovy took on an autocratic form under Ivan III which it had never had before. This was due not merely to the natural consequence of the hegemony of Moscow over the other Russian lands, but even more to the simultaneous growth of new and exotic principles falling upon a soil already prepared for them. After the fall of Constantinople, Orthodox canonists were inclined to regard the Muscovite grand dukes as the successors of the emperors.

This movement coincided with a change in the family circumstances of Ivan III. After the death of his first consort, Maria of Tver (1467), Ivan III wedded Sophia Paleologue (also known by her original Greek and Orthodox name of Zoe), daughter of Thomas Palaeologus , despot of Morea, who claimed the throne of Constantinople as the brother of Constantine XI, last Byzantine emperor, at the suggestion of Pope Paul II (1469), who hoped thereby to bind Russia to the holy see.

The main condition of their union was that their children would not inherit the throne of Moscow. However, frustrating the Pope's hopes of re-uniting the two faiths, the princess reverted to Orthodoxy. Due to her family traditions, she awoke imperial ideas in the mind of her consort. It was through her influence that the ceremonious etiquette of Constantinople (along with the imperial double-headed eagle and all that it implied) was adopted by the court of Moscow.

The grand duke from this time forth held aloof from his boyars. He never lead another military campaign himself; he relied on his generals. The old patriarchal systems of government vanished. The boyars were no longer consulted on affairs of state. The sovereign became sacred, while the boyars were reduced to the level of slaves, absolutely dependent on the will of the sovereign. The boyars naturally resented such insulting revolution, and struggled against it. They had some success in the beginning. At one point, the boyars set up Sophia and attempted to alienate her from Ivan. However, the clever woman prevailed in the end, and it was her son Vasili III, not Maria of Tver's son, Ivan the Young, who was ultimately crowned co-regent with his father on April 14, 1502.

It was during the reign of Ivan III that the new Russian Sudebnik, or law code, was compiled by the scribe Vladimir Gusev. Ivan did his utmost to make his capital a worthy successor to Constantinople, and with that vision invited many foreign masters and craftsmen to settle in Moscow. The most noted of these was the Italian Ridolfo di Fioravante, nicknamed Aristotle because of his extraordinary knowledge, who built several cathedrals and palaces in the Kremlin. This extraordinary monument of the Muscovite art remains a lasting symbol of the power and glory of Ivan III.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- 1911 edition of Encyclopedia Britannica (public domain).

- von Herberstei, Sigismund. 450 Jahre Sigismund von Herbersteins Rerum Moscoviticarum Commentarii : 1549-1999. Wiesbaden : Harrassowitz, 2002. ISBN 3447046252

- XPOHOC. [1] Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- Russian History in the Mirror of Fine Art Retrieved May 29, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved March 10, 2018.

- Robert Beard. The Sudebnik

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.