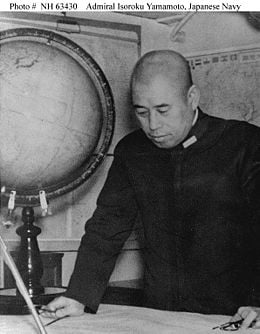

Isoroku Yamamoto

| Isoroku Yamamoto | |

|---|---|

| April 4, 1884 – April 18,1943 | |

Fleet Admiral (Admiral of the Fleet) Isoroku Yamamoto | |

| Place of birth | Nagaoka, Niigata Prefecture, Japan |

| Place of death | Solomon Islands |

| Allegiance | Imperial Japanese Navy |

| Years of service | 1901-1943 |

| Rank | Fleet Admiral, Commander-in-Chief |

| Unit | Combined Fleet |

| Commands held | Kitakami Isuzu Akagi Japan Naval Air Command Japan Navy Ministry Japan Naval Air Command Japan 1st Fleet Combined Fleet Japan 1st Battleship Division Division |

| Battles/wars | Russo-Japanese War World War II |

| Awards | Grand Cordon of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun Paulownia Blossoms, Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Order of the Golden Kite (1st class), Order of the Golden Kite (2nd class), Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords |

Isoroku Yamamoto(Japanese: 山本五十六, Yamamoto Isoroku) (April 4,1884 – April 18, 1943) was a Fleet Admiral and Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II, graduate of Imperial Japanese Naval Academy and an alumnus of the U.S. Naval War College and Harvard University (1919 - 1921). Yamamoto was among the Imperial Japanese Navy's most able admirals and is highly respected in Japan. In the United States he is widely regarded as a clever, intelligent and dangerous opponent who resisted going to war, but once the decision was made did his utmost for his country. He is most remembered for planning the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Yamamoto, who had studied in the United States, and had spent time there during two postings as naval attaché in Washington D.C., had an understanding of American character and a profound respect for US military power. In December, 1936, Yamamoto was appointed Vice Minister of the Japanese navy, and joined the ranks of Japan’s government policymakers, but threats of assassination from right-wing extremists who did not like his liberal attitude towards the United States prompted the Prime Minister to appoint him, for his own protection, Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet in August 1939. In November of 1940, Yamamoto warned Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, to avoid war with the United States. Yamamoto undertook many changes and reorganizations of the Imperial Japanese Navy, including the development of an air force based on aircraft carriers and on land. He died in 1943 in an American ambush during an inspection tour of forward positions in the Solomon Islands. His death was a major blow to Japanese military morale during World War II.

Family Background

Yamamoto Isoroku was born Takano Isoroku on April 4, 1884, in the small village of Kushigun Sonshomura near Nagaoka, Niigata Prefecture, the sixth son of an impoverished schoolteacher, Sadayoshi Teikichi, and his second wife Mineko. His father was a lower-ranking samurai of Nagaoka-Han, belonging to the Echigo clan, an ancient warrior people who had resisted the unification of Japan under the Meiji emperor. His father chose the name Isoroku (meaning 56 in Japanese) because that was his age when the boy was born. Soon after his birth, his father became headmaster of the primary school in nearby Nagaoka.

Early Career

At 16, after passing the competitive entrance examinations, Isoroku enrolled in the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy at Etajima, off the shore of Hiroshima. He spent three years there in study and rigorous physical training, and then another year on a square-rigged windjammer. After graduating from the Naval Academy in 1904, Yamamoto served on the Japanese cruiser Nisshin during the Russo-Japanese War. On the Nisshin, which was part of the protective screen for Admiral Togo Heihachiro's flagship Mikasa, Isoroku observed firsthand the tactics of one of the world's greatest admirals. From Togo, he learned, above al things, the need for surprise in battle. In a letter to his family, the young seaman described the Battle of Tsushima:

When the shells began to fly above me I found I was not afraid. The ship was damaged by shells and many were killed. At 6:15 in the evening a shell hit the Nisshin and knocked me unconscious. When I recovered I found I was wounded in the right leg and two fingers of my left hand were missing. But the Russian ships were completely defeated and many wounded and dead were floating on the sea.

He was later nicknamed “80 sen” by some of his favorite geisha because of the two fingers (the index and middle fingers) missing from his left hand.

From 1904 until the outbreak of World War I, Isoroku went on training cruises to Korea and China, traveled to the west coast of the United States, and visited every major port in Australia. In 1914 he entered the Naval Staff College at Tsukiji, a prerequisite for high command, emerging as a lieutenant commander in 1916. Upon graduation in 1916, he was appointed to the staff of the Second Battle Squadron.

In 1916, Isoroku was also adopted by the wealthy and prestigious Yamamoto family and, at a formal ceremony in a Buddhist temple, took the Yamamoto name. Such adoptions were common among Japanese families lacking a male heir, who sought a means of carrying on the family name.

In 1918, Yamamoto married Reiko Mihashi, the daughter of a dairy farmer from Niigata Prefecture. The couple had four children. At the same time, Yamamoto made no secret of his relationships with geisha; the geisha houses of his mistresses were decorated with his calligraphy, which was much admired, and he earned a large second income from his winnings at bridge and poker. He once remarked, "If I can keep 5,000 ideographs in my mind, it is not hard to keep in mind 52 cards."

Preparing for War, 1920s and 1930s

Yamamoto was fundamentally opposed to war with the United States because his studies at the U.S. Naval War College and Harvard University (1919-1921), his tour as an admiral's aide, and two postings as naval attaché in Washington D.C had given him an understanding of the military and material resources available to the Americans. In 1919, Yamamoto began two years of study at Harvard University, where he concentrated on the oil industry. In July of 1921 he returned to Japan with the rank of commander and was appointed instructor at the naval staff college in Tokyo. In June of 1923, he was promoted to captain of the cruiser Fuji. In 1924, at the age of forty, he changed his specialty from gunnery to naval aviation, after taking flying lessons at the new air-training center at Kasumigaura, 60 miles northeast of Tokyo. Within three months, he was director of studies. Yamamoto's handpicked pilots became an élite corps, the most sought-after arm of the Japanese navy. His first command was the cruiser Isuzu in 1928, followed by the aircraft carrier Akagi. He was then appointed to the navy ministry's naval affairs bureau, where he was an innovator in the areas of air safety and navigation Yamamoto was a strong proponent of naval aviation, and (as vice admiral) served as head of the Aeronautics’ Department before accepting a post as commander of the First Carrier Division.

From January, 1926 until March of 1928, Yamamoto served as naval attaché to the Japanese embassy in Washington, which was there to investigate America's military might. Historian Gordon W. Prange describes Yamamoto at the height of his powers as:

a man short even by Japanese standards (five feet three inches), with broad shoulders accentuated by massive epaulets and a thick chest crowded with orders and medals. But a strong, commanding face dominates and subdues all the trappings. The angular jaw slants sharply to an emphatic chin. The lips are full, cleancut, under a straight, prominent nose; the large, well-spaced eyes, their expression at once direct and veiled, harbor potential amusement or the quick threat of thunder.

During his entire career, Yamamoto fought for naval parity with the other great sea powers. He participated in the second London Naval Conference of 1930 as a Rear Admiral and as a Vice Admiral at the 1934 London Naval Conference, as the government felt that a career military specialist was needed to accompany the diplomats to the arms limitations talks. Yamamoto firmly rejected any further extension of the 5-5-3 ratio, a quota established at the Washington Conference of 1921-1922, which had limited the Japanese building of heavy warships to 60 percent of American and British construction. He called the 5-5-3 ratio a "national degradation," and demanded full equality.

From December of 1930 to October of 1933, Yamamoto headed the technical section of the navy's aviation bureau, and from December of 1935 to December of 1936, he was chief of the bureau itself, and directed the entire naval air program including carriers, seaplanes, and land-based craft. During the attempted coup of February 26, 1936, in which military nationalists attempted to topple Japan's parliamentary government and establish direct military rule, Yamamoto’s junior officers at the admiralty asked him to join the rebels. He ordered them to return to their desks immediately, and they responded without a word.

In December, 1936, Yamamoto was appointed Vice Minister of the Japanese navy, and joined the ranks of Japan’s elite policymakers. Yamamoto was reluctant to accept the post, as he preferred air command and did not like politics. In his new post, he promoted the development of aircraft carriers and opposed the building of more battleships, which he said could be easily destroyed by torpedos dropped from planes. He declared, "These [battle]ships are like elaborate religious scrolls which old people hung up in their homes. They are of no proved worth. They are purely a matter of faith - not reality."

Attitude toward Nazi Germany

While in office, he opposed the army’s proposed alliance with Nazi Germany, warning that such an agreement would lead to war with the world's two strongest naval powers, the United States and Britain, and possibly also with the Soviet Union. He pointed out that the Imperial Navy, and the entire Japanese economy depended on imports of raw materials from the United States. Yamamoto personally opposed the invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the subsequent land war with China (1937), and the Tripartite Pact (1940) with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. In 1937, when the Japanese army invaded China, he told a friend, "The stupid army has started again."

On December 12, 1937, Japanese planes bombed the U.S. gunboat Panay, cruising China's Yangtse River, killing three Americans and wounding 43. As Deputy Navy Minister, he apologized to United States Ambassador Joseph C. Grew, saying, "The Navy can only hang its head."

These issues made him unpopular and a target of assassination by pro-war militarists, who supposedly offered 100,000 yen as a reward for the person who carried it out. Tanks and machine guns were installed in the Navy Ministry as protection. On August 30, 1939, two days before Hitler invaded Poland, Yamamoto was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, and sent to sea, partly to make him less accessible to assassins. He was promoted to full admiral on November15, 1940. Yamamoto warned Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, with a prescient statement, to avoid war with the United States: "If I am told to fight… I shall run wild for the first six months… but I have utterly no confidence for the second or third year."

In naval matters, Yamamoto opposed the building of the super-battleships Yamato and Musashi as an unwise investment of resources.

Yamamoto was responsible for a number of innovations in Japanese naval aviation. Although his memory is associated with aircraft carriers due to the Pearl Harbor attack and the Battle of Midway, Yamamoto did more to influence the development of land-based naval aviation, particularly the G3M and G4M medium bombers. He demanded planes with a long range and the ability to carry a torpedo, in accordance with Japanese concepts of destroying the American fleet as it advanced across the Pacific in war. The planes did achieve a long range, but long-range fighter escorts were not available. They were lightly built and when fully fueled, they were especially vulnerable to enemy fire. This earned the G4M the sardonic nick-name "the Flying Cigarette Lighter." Ironically, Yamamoto later died in one of these aircraft.

The range of the G3M and G4M crated a demand for long-range fighter aircraft. The result partly drove the requirements for the A6M Zero, which was as noteworthy for its range as for its maneuverability. These qualities were achieved at the expense of light construction and flammability that later contributed to the A6M's high casualty rates as the war progressed.

Moving toward war

As Japan moved toward war during 1940, Yamamoto introduced strategic as well as tactical innovations, again with mixed results. Prompted by talented young officers such as Minoru Genda, Yamamoto approved the reorganization of Japanese carrier forces into the First Air Fleet, a consolidated striking force that gathered Japan's six largest carriers into one unit. This innovation gave great striking capacity, but also concentrated the vulnerable carriers into a compact target. Yamamoto also oversaw the organization of a similar large land-based organization, the 11th Air Fleet, which would later use the G3M and G4M to neutralize American air forces in the Philippines and sink the British Force "Z."

In January 1941, Yamamoto went even farther and proposed a radical revision of Japanese naval strategy. For two decades, in keeping with the doctrine of Captain Alfred T. Mahan,[1] the Naval General Staff had planned on using Japanese light surface forces, submarines and land-based air units to whittle down the American Fleet as it advanced across the Pacific, until the Japanese Navy engaged it in a climactic "Decisive Battle" in the northern Philippine Sea (between the Ryukyu Islands and the Marianas Islands), with battleships meeting in the traditional exchange between battle lines. Correctly pointing out this plan had never worked even in Japanese war games, and painfully aware of American strategic advantages in military productive capacity, Yamamoto proposed instead to seek a decision with the Americans by first reducing their forces with a preemptive strike, and following it with an offensive, rather than a defensive, "Decisive Battle." Yamamoto hoped, but probably did not believe, that if the Americans could be dealt such terrific blows early in the war, they might be willing to negotiate an end to the conflict. As it turned out, however, the note officially breaking diplomatic relations with the United States was delivered late, and he correctly perceived that the Americans would be resolved upon revenge and unwilling to negotiate.

The Naval General Staff proved reluctant to go along with his ideas, and Yamamoto was eventually driven to capitalize on his popularity in the fleet by threatening to resign in order to get his way. Admiral Osami Nagano and the Naval General Staff eventually caved in to this pressure, but only approved the attack on Pearl Harbor as a means of gaining six months to secure the resources of the Netherlands East Indies without the interference of the American navy.

The First Air Fleet commenced preparations for the Pearl Harbor Raid, tackling a number of technical problems, including how to launch torpedoes in the shallow water of Pearl Harbor and how to craft armor-piercing bombs by machining down battleship gun projectiles.[2][3]

The Attack on Pearl Harbor, December 1941

As Yamamoto had planned, the First Air Fleet of six carriers, armed with about 390 planes, commenced hostilities against the Americans on December 7, 1941, launching 350 of those aircraft against Pearl Harbor in two waves. The attack was a complete success, according to the parameters of the mission, which sought to sink at least four American battleships and prevent the U.S. Fleet from interfering in Japan's southward advance for at least six months. American aircraft carriers were also considered choice targets, but were not given priority over battleships. As a tactical raid, the attack was an overall victory, handily achieving some objectives while only losing 29 aircraft and five miniature submarines. Strategically, it was a failure; the raid on Pearl Harbor, instead of crushing the morale of the American people, galvanized them into action and made them determined to get revenge.

Five American battleships were sunk, three damaged, and eleven other cruisers, destroyers and auxiliaries were sunk or seriously damaged. The Japanese lost only 29 aircraft, but suffered damage to more than 111 aircraft. The damaged aircraft were disproportionately dive- and torpedo-bombers, seriously impacting the firepower available to exploit the first two waves' success, and First Air Fleet Commander Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo withdrew. Yamamoto later lamented Nagumo's failure to seize the initiative to seek out and destroy the American carriers which were absent from the harbor, or further bombard various strategically important facilities on Oahu. Nagumo had absolutely no idea where the American carriers might be, and by remaining in place while his forces searched for them, ran the risk that his own force might be found first and attacked while his aircraft were absent. Further, his aircraft lacked appropriate ordinance for attacking the machine tools and drydocks of the shipyard, or even the fuel tanks, whose destruction could have been more serious losses than the fighting ships themselves. In any case, insufficient daylight remained after recovering the aircraft from the first two waves for the carriers to launch and recover a third wave before dark, and Nagumo's escorting destroyers did not carry enough fuel for him to loiter long. Much has been made of Yamamoto's regret at the lost opportunities, but it is instructive to note that he did not punish Nagumo in any way for his withdrawal, which was, after all, according to the original plan, and the prudent course to take.

On a political level, the attack was a disaster for Japan, rousing American passions for revenge for the "sneak attack." It had been expected that the Japanese would begin war with a surprise attack, just as they had begun all their modern wars, but not at Pearl Harbor. The shock of the attack on an unexpected place, with such devastating results and without the "fair play" of a declaration of war, galvanized the American public's determination to avenge the attack.

As a strategic blow intended to prevent American interference in the Netherlands East Indies for six months, the attack was a success, but unbeknownst to Yamamoto, a pointless one. The U.S. Navy had abandoned any intention of attempting to charge across the Pacific to the Philippines at the outset of war in 1935 (in keeping with the evolution of War Plan Orange). In 1937, the U.S. Navy had further determined that the fleet could not be fully manned to wartime levels in less than six months, and that the myriad other logistic assets necessary to execute a trans-Pacific movement simply did not exist and would require two years to construct, after the onset of war. In 1940, U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Harold Stark had penned "Plan Dog," which emphasized a defensive war in the Pacific while the U.S. concentrated on defeating Nazi Germany first, and consigned Admiral Husband Kimmel's Pacific Fleet to merely keeping the Imperial Japanese Navy out of the eastern Pacific and away from the shipping lanes to Australia.[4][5][6]

Six Months of Victories, December 1941 to May 1942

With the American Fleet largely neutralized at Pearl Harbor, Yamamoto's Combined Fleet turned to the task of executing the larger Japanese war plan devised by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy General Staff. The First Air Fleet proceeded to make a circuit of the Pacific, striking American, Australian, Dutch and British installations from Wake Island to Australia to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in the Indian Ocean. The 11th Air Fleet caught the American 5th Air Force on the ground in the Philippines hours after Pearl Harbor, and then proceeded to sink the British Force "Z" (battleship HMS “Prince of Wales,” 1939) and battlecruiser HMS Repulse (1916) underway at sea.

Under Yamamoto's able subordinates, Vice Admirals Jisaburo Ozawa, Nobutake Kondo and Ibo Takahashi, the Japanese swept the inadequate remaining American, British, Dutch and Australian naval assets from the Netherlands East Indies in a series of amphibious landings and surface naval battles that culminated in the Battle of the Java Sea on February 27, 1942. With the occupation of the Netherlands East Indies, and the reduction of the remaining American positions in the Philippines to forlorn outposts on the Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor island, the Japanese had secured their oil- and rubber-rich "Southern Resources Area."

Having achieved their initial aims with surprising speed and little loss (against enemies ill-prepared to resist them), the Japanese paused to consider their next moves. Since neither the British nor the Americans were willing to negotiate, thoughts turned to securing and protecting their newly seized territory, and acquiring more with an eye toward additional conquest, or attempting to force one or more enemies out of the war.

Competing plans developed at this stage, including thrusts to the west against India, the south against Australia and the east against the United States. Yamamoto was involved in this debate, supporting different plans at different times with varying degrees of enthusiasm and for varying purposes, including "horse-trading" for support of his own objectives.

Plans included ideas as ambitious as invading India or Australia, as well as seizing theHawaiian Islands. These grandiose ventures were inevitably set aside; the Army could not spare enough troops from China for the first two, nor shipping to support the latter two. (Shipping was allocated separately to the Imperial Japanese Navy and the Imperial Japanese Army, and jealously guarded.[7]) Instead, the Imperial General Staff supported an Army thrust into Burma, in hopes of linking up with Indian Nationalists revolting against British rule, and attacks in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands designed to imperil Australia's sea line of communication with the United States. Yamamoto agitated for an offensive Decisive Battle in the east to finish the American fleet, but the more conservative Naval General Staff officers were unwilling to risk it.

In the midst of these debates, the Doolittle Raid struck Tokyo and the surrounding areas, demonstrating the threat posed by the American aircraft carriers, and giving Yamamoto an event he could exploit to promote his strategy. The Naval General Staff agreed to Yamamoto's Midway (MI) Operation, subsequent to the first phase of the operations against Australia's link with America, and concurrent with their own plan to seize positions in the Aleutian Islands.

Yamamoto rushed planning for the Midway and Aleutions missions, while dispatching a force under Rear Admiral Takeo Takagi, including the Fifth Carrier Division (the large, new carriers Shōkaku and Japanese aircraft carrier Zuikaku), to support the effort to seize the islands of Tulagi and Guadalcanal for seaplane and airplane bases, and the town of Port Moresby on Papua New Guinea's south coast facing Australia.

The Port Moresby Operation proved an unwelcome reverse. Although Tulagi and Guadalcanal were taken, the Port Moresby invasion fleet turned back when Takagi clashed with an American carrier task force in the Battle of the Coral Sea in early May. Although the Japanese sank the American carrier, USS Lexington, in exchange for a smaller carrier, the Americans damaged the carrier Shōkaku so badly that she required dockyard repairs. Just as importantly, Japanese operational mishaps and American fighters and anti-aircraft fire devastated the dive bomber and torpedo plane elements of both Shōkaku’s and Zuikaku’s air groups. These losses sidelined Zuikaku while she awaited replacement aircraft and replacement aircrew, and saw to tactical integration and training. These two ships would be sorely missed a month later at Midway.[8][9][10]

The Battle of Midway, June 1942

Yamamoto's plan for the Midway Invasion was an extension of his efforts to knock the U.S. Pacific Fleet out of action long enough for Japan to fortify her defensive perimeter in the Pacific island chains. Yamamoto felt it necessary to seek an early, offensive decisive battle.

The strike on the Aleutian Islands was long believed to have been an attempt by Yamamoto to draw American attention—and possibly carrier forces—north from Pearl Harbor by sending his Fifth Fleet (2 light carriers, 5 cruisers, 13 destroyers and 4 transports) against the Aleutians, raiding Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island and invading the more distant islands of Kiska and Attu. Recent scholarship[11] using Japanese language documents has revealed that it was instead an unrelated venture of the Naval General Staff, which Yamamoto agreed to conduct concurrently with the Midway operation, in exchange for the latter's approval.

While Fifth Fleet attacked the Aleutians, First Mobile Force (4 carriers, 2 battleships, 3 cruisers, and 12 destroyers) would raid Midway and destroy its air force. Once this was neutralized, Second Fleet (1 light carrier, 2 battleships, 10 cruisers, 21 destroyers, and 11 transports) would land 5,000 troops to seize the atoll from the American Marines.

The seizure of Midway was expected to draw the American carriers west into a trap where the First Mobile Force would engage and destroy them. Afterward, First Fleet (1 light carrier, 7 battleships, 3 cruisers and 13 destroyers), in conjunction with elements of Second Fleet, would mop up remaining American surface forces and complete the destruction of the Pacific Fleet.

To guard against mischance, Yamamoto initiated two security measures. The first was an aerial reconnaissance mission (Operation K) over Pearl Harbor to ascertain if the American carriers were there. The second was a picket line of submarines to detect the movement of the American carriers toward Midway in time for First Mobile Force, First Fleet, and Second Fleet to combine against it. During the actual event, the first was aborted and the second delayed until after American carriers had already passed the area where the submarines were deployed.

The plan was a compromise and hastily prepared, but to the Japanese, it appeared well thought out, well organized, and finely timed. Against 4 carriers, 2 light carriers, 11 battleships, 16 cruisers and 46 destroyers from Japan that were likely to be in the area of the main battle, the Americans could field only 3 carriers, 8 cruisers, and 15 destroyers. The disparity appeared crushing. Only in numbers of available aircraft and submarines was there near parity between the two sides. Despite various problems which developed in the execution, it appeared, barring something extraordinary, that Yamamoto held all the cards.

Codes deciphered

Unfortunately for Yamamoto, something extraordinary had happened. The worst fear of any commander is for an enemy to learn his battle plan in advance, and that was exactly what American cryptographers had done, by breaking the Japanese naval code D (known to the U.S. as JN-25). As a result, Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander of the Pacific Fleet, was able to circumvent both of Yamamoto's security measures and position his outnumbered forces in the exact position to conduct a devastating ambush. By Nimitz's calculation, his three available carrier decks, plus Midway, gave him rough parity with Nagumo's First Mobile Force.

Following a foolish nuisance raid by Japanese flying boats in May,[12] Nimitz dispatched a minesweeper to guard the intended refueling point for Operation K, causing the reconnaissance mission to be aborted and leaving Yamamoto ignorant of whether Pacific Fleet carriers were still at Pearl Harbor. (It remains unclear why Yamamoto permitted the earlier raid, when pre-attack reconnaissance was essential to the success of Midway.) Nimitz also dispatched the American carriers toward Midway early, and they passed the intended “picket line” force of submarines before they were put in place, negating Yamamoto's back-up security measure. Nimitz's carriers then positioned themselves to ambush the First Mobile Force when it struck Midway. A token cruiser and destroyer force was dispatched toward the Aleutians, but otherwise ignored the attack there. On June 4, 1942, days before Yamamoto expected American carriers to interfere in the Midway operation, they destroyed the four carriers of the First Mobile Force, catching the Japanese carriers at precisely their most vulnerable moment.

With his air power destroyed and his forces not yet concentrated for a fleet battle, Yamamoto was unable to maneuver his remaining units to trap the American forces when Admiral Raymond Spruance, believing (based on a mistaken submarine report) that the Japanese still intended to invade, prudently withdrew to the east, in a position to further defend Midway.[13] (He did not apprehend the severe risk of a night surface battle, in which his carriers would be at a disadvantage, not knowing Yamato was on the Japanese order of battle.[14]) Correctly perceiving that he had lost, Yamamoto aborted the invasion of Midway and withdrew. The defeat ended Yamamoto's six months of success and marked the high tide of Japanese expansion.

Yamamoto's plan for Midway Invasion has been the subject of much criticism. Many commentators state that it violated the principle of concentration of force, and was overly complex. Others point out similarly complex Allied operations that were successful, and note the extent to which the American intelligence coup derailed the operation before it began. Had Yamamoto's dispositions not disabled Nagumo pre-attack reconnaissance flights, the cryptanalytic success, and the unexpected appearance of the American carriers, would have been irrelevant.[15]

Actions after Midway

The Battle of Midway solidly checked Japanese momentum, but it was not actually the turning point of the Pacific War. The Imperial Japanese Navy planned to resume the initiative with operation (FS), aimed at eventually taking Samoa and Fiji to cut the American life-line to Australia. This was expected to short-circuit the threat posed by General Douglas MacArthur and his American and Australian forces in New Guinea. To this end, development of the airfield on Guadalcanal continued and attracted the baleful eye of United States Admiral Ernest King.

King ramrodded the idea of an immediate American counter-attack, to prevent the Japanese from regaining the initiative, through the Joint Chiefs of Staff. This precipitated an American invasion of Guadalcanal and pre-empted the Japanese plans, with Marines landing on the island in August 1942 and starting a bitter struggle that lasted until February 1943 and began an attrition that Japanese forces could ill-afford.

Admiral Yamamoto remained in command, retained, at least in part, to avoid diminishing the morale of the Combined Fleet. However, he had lost face in the Midway defeat and the Naval General Staff were disinclined to indulge further gambles. This reduced Yamamoto to pursuing the classic defensive Decisive Battle strategy he had attempted to overturn.

The attack on Guadalcanal over-extended the Japanese, who were attempting to simultaneously support fighting in New Guinea, guard the Central Pacific and prepare to conduct the FS Operation. The FS Operation was abandoned and the Japanese attempted to fight in both New Guinea and Guadalcanal at the same time. A lack of shipping, shortage of troops, and a disastrous inability to coordinate Army and Navy activities consistently undermined their efforts.

Yamamoto committed Combined Fleet units to a series of small attrition actions that stung the Americans, but suffered losses in return. Three major efforts to carry the island precipitated a pair of carrier battles that Yamamoto commanded personally at the Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz Islands in September and October, and finally a wild pair of surface engagements (Naval Battle of Guadalcanal) in November, all timed to coincide with Japanese Army pushes. The timing of each major battle was successively derailed when the Army could not hold up its end of the operation. Yamamoto's forces caused considerable loss and damage, but he could never draw the Americans into a decisive fleet action. As a result, the Japanese Navy gradually lost its strength.

Severe losses of dive-bomber and torpedo-bomber crews in the carrier battles, emasculated the already depleted carrier air groups. Particularly harmful, however, were losses of destroyers in nighttime “Tokyo Express” supply runs, made necessary by Japan’s inability to protect slower supply convoys from daytime air attacks. [16] With Guadalcanal lost in February 1943, there was no further attempt to seek a major battle in the Solomon Islands although smaller attrition battles continued. Yamamoto shifted the load of the air battle from the depleted carriers to the land-based naval air forces. Some of these units were positioned at forward bases in the Solomon Islands, and while on an inspection trip to these positions on April 18, 1943, Yamamoto once more fell victim—this time personally—to American code-breaking. A squadron of American P-38 fighters ambushed his plane and its escorts.[17]

Death

To boost morale following the defeat at Guadalcanal, Yamamoto decided to make an inspection tour throughout the South Pacific. On April 14, 1943, the US naval intelligence effort, code-named "Magic," intercepted and decrypted a message containing specific details regarding Yamamoto's tour, including arrival and departure times and locations, as well as the number and types of planes that would transport and accompany him on the journey. Yamamoto, the itinerary revealed, would be flying from Rabaul to Ballalae Airfield, on an island near Bougainville in the Solomon Islands, on the morning of April 18, 1943.

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt requested Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to "Get Yamamoto." Knox instructed Admiral Chester W. Nimitz of Roosevelt's wishes. Admiral Nimitz consulted Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., Commander, South Pacific, then authorized a mission on April 17 to intercept Yamamoto's flight en route and down it.

The 339th Fighter Squadron of the 347th Fighter Group, 13th Air Force, was assigned the mission, since only their P-38 Lightning aircraft possessed the range to intercept and engage. Pilots were informed that they were intercepting an "important high officer," although they were not aware who their actual target was.

On the morning of April 18, although urged by local commanders to cancel the trip for fear of ambush, Yamamoto's planes left Rabaul as scheduled for the 315-mile trip. Shortly after, eighteen specially-fitted P-38s took off from Guadalcanal. They wave-hopped most of the 430 miles to the rendezvous point, maintaining radio silence. At 09:34 Tokyo time, the two flights met and a dogfight ensued between the P-38s and the six Zeroes escorting Yamamoto.

First Lieutenant Rex T. Barber engaged the first of the two Japanese bombers, which was carrying Yamamoto, and sprayed the plane with gunfire until it began to spew smoke from its left engine. Barber turned away to attack the other bomber as Yamamoto's plane crashed into the jungle. Afterwards, another pilot, Capt Thomas George Lanphier, Jr., claimed he had shot down the lead bomber, which led to a decades-old controversy until a team inspected the crash site to determine direction of the bullet impacts. Most historians now credit Barber with the claim.

One US pilot was killed in action. The crash site and body of Admiral Yamamoto were found the next day in the jungle north of the then-coastal site of the former Australian patrol post of Buin by a Japanese search and rescue party, led by Army engineer Lieutenant Hamasuna. According to Hamasuna, Yamamoto had been thrown clear of the plane's wreckage, his white-gloved hand grasping the hilt of his katana, still upright in his seat under a tree. Hamasuna said Yamamoto was instantly recognizable, head dipped down as if deep in thought. A post-mortem of the body disclosed that Yamamoto had received two gunshot wounds, one to the back of his left shoulder and another to his left lower jaw that exited above his right eye. Despite the evidence, the question of whether or not the Admiral initially survived the crash has been a matter of controversy in Japan.

This proved to be the longest fighter-intercept mission of the war. In Japan it became known as the "Navy kō Incident"(海軍甲事件) (in the game of Go, "ko" is an attack one can not immediately respond to). It raised morale in the United States, and shocked the Japanese, who were officially told about the incident only on May 21, 1943. To cover up the fact that the Allies were reading Japanese code, American news agencies were told that civilian coast-watchers in the Solomon Islands saw Yamamoto boarding a bomber in the area. They also did not publicize the names of the pilots that attacked Yamamoto's plane because one of them had a brother who was a prisoner of the Japanese, and U.S. military officials feared for his safety.

Captain Watanabe and his staff cremated Yamamoto's remains at Buin, and the ashes were returned to Tokyo aboard the battleship Musashi, Yamamoto's last flagship. Yamamoto was given a full state funeral on June 3, 1943, where he received, posthumously, the title of Fleet Admiral and was awarded the Order of the Chrysanthemum, (1st Class). He was also awarded Nazi Germany's Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords. Part of his ashes were buried in the public cemetery in Tama, Tokyo (多摩霊園), and the remainder at his ancestral burial grounds at the Chuko-ji Temple in Nagaoka City, Niigata.

Quotes

- "Should hostilities once break out between Japan and the United States, it is not enough that we take Guam and the Philippines, nor even Hawaii and San Francisco. We would have to march into Washington and sign the treaty in the White House. I wonder if our politicians (who speak so lightly of a Japanese-American war) have confidence as to the outcome and are prepared to make the necessary sacrifices." [1]

- "I fear that all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve." - attributed to Yamamoto in the film Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), about the attack on Pearl Harbor, although it is generally considered apocryphal.

Film Portrayals

Several motion pictures depict the character of Isoroku Yamamoto. One of the most notable films is the movie Tora! Tora! Tora!. The 1970 film, which depicts the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, is considered by many to be the definitive look at the battle from both sides of the conflict. The film features Japanese actor Sô Yamamura as Yamamoto. He is seen planning the Japanese attack. At the end of the film, he states his belief that all that was accomplished was the awakening of a "sleeping giant."

The motion picture Midway was relased in 1976. An epic look at the battle that turned the tide of the war in the Pacific, the film features Toshiro Mifune as Yamamoto. We see him as he plans the attack on Midway Atoll, and sees his plans fall apart as all four Japanese carriers are destroyed during the battle of June 4-6, 1942.

The latest depiction of Yamamoto on film was in the 2001 release of the epic Pearl Harbor, produced by Jerry Bruckheimer. While mostly focused on the love triangle between the three main characters, the film shows several scenes depicting the Japanese planning of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Yamamoto is played by Oscar-nominated actor Mako. One of Yamamotos most notable quotes in the film is: "A brilliant man would find a way not to fight a war."

Notes

- ↑ Alfred T. Mahan. The Influence of Seapower on History. (original 1957) (Books on Tape, Inc., 1995)

- ↑ David C. Evans, and Mark R. Peattie. Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy 1887–1941. (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1997).

- ↑ Mark R. Peattie. Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power, 1909–1941. (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. 2002).

- ↑ Evans & Peattie 1997

- ↑ Edward S. Miller. War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945. (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1991)

- ↑ Peattie 2002.

- ↑ Mark P. Parillo. Japanese Merchant Marine in World War II. (Annapolis: Naval Inst Press, 1993)

- ↑ Paul S. Dull. A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1978)

- ↑ Evans & Peattie 1997

- ↑ John B. Lundstrom. The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway. (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1984)

- ↑ John Parshall & Anthony Tully in "Shattered Sword" 2006

- ↑ Wilfred J. "Jasper" Holmes. Double-Edged Secrets. (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1979)

- ↑ Clay Blair, Jr. Silent Victory. (Philadelphia: Lippincott), 1975.

- ↑ Blair, Jr.

- ↑ H.P. Willmott. Barrier and the Javelin. (Annapolis: United States Naval Institute Press, 1983).

- ↑ Parillo, 1983

- ↑ Dull 1978.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Agawa, Hiroyuki, and John Bester (trans.). The Reluctant Admiral. New York: Kodansha, 1979. ISBN 4770025394. A definitive biography of Yamamoto in English. This book explains much of the political structure and events within Japan that lead to the war.

- Blair, Jr. Clay, Silent Victory. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1975.

- Davis, Donald A. Lightning Strike: The Secret Mission to Kill Admiral Yamamoto and Avenge Pearl Harbor. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2005. ISBN 0312309066.

- Dull, Paul S. A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1978. ISBN 0870210971.

- Evans, David C. and Mark R. Peattie. Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1997. ISBN 0870211927.

- Glines, Carroll V. Attack on Yamamoto (1st edition). New York: Crown, 1990. ISBN 0517577283. Glines documents both the mission to shoot down Yamamoto and the subsequent controversies with thorough research, including personal interviews with all surviving participants and researchers who examined the crash site.

- Holmes, W. Jasper. Double-Edge Secrets. U.S. Naval Intelligence Operations in the Pacific During World War II. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1979.

- Holmes, W. Jasper. Undersea Victory: The Influence of Submarine Operations on the War in the Pacific. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1966. (reprinted by Kensington as: Underseas Victory.

- Hoyt, Edwin P. Yamamoto: The Man Who Planned Pearl Harbor. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1990. ISBN 158574428X.

- Lundstrom, John B. The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1984. ISBN 0870211897.

- Mahan, Alfred T. The Influence of Seapower on History. (original 1957) audiotape. Books on Tape, Inc., 1995. ISBN-10: 0736631488

- Miller, Edward S. War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1991. ISBN 0870217593.

- Parillo, Mark P. Japanese Merchant Marine in World War II. Annapolis: Naval Inst Press, 1993. ISBN 1557506779

- Peattie, Mark R. Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power, 1909–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2002. ISBN 1557504326.

- Prados, John. Combined Fleet Decoded: The Secret History of American Intelligence and the Japanese Navy in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2001. ISBN 1557504318.

- Ugaki, Matome, and Masataka Chihaya, (trans.) Fading Victory: The Diary of Admiral Matome Ugaki, 1941-45. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1991. ISBN 0822954621. Provides a high-level view of the war from the Japanese side, from the diaries of Yamamoto's Chief of Staff, Admiral Matome Ugaki. Provides evidence of the intentions of the imperial military establishment to seize Hawaii and to operate against the British navy in the Indian Ocean. Translated by Masataka Chihaya, this edition contains extensive clarifying notes from the U.S. editors derived from U.S. military histories.

- Willmott, H.P. Barrier and the Javelin. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute Press, 1983.

External links

All links retrieved March 7, 2018.

- "Yamamoto Mission" Pacific Wrecks.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.