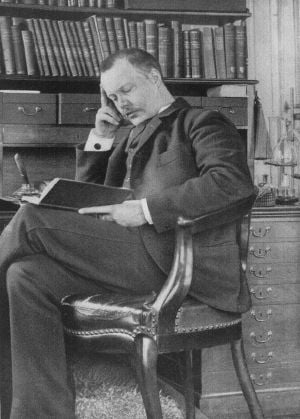

Houston Stewart Chamberlain

Houston Stewart Chamberlain (September 9, 1855 - January 9, 1927) was a British-born author of books on political philosophy, natural science and his posthumous father-in-law Richard Wagner. His two-volume book Die Grundlagen des Neunzehnten Jahrhunderts (The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century) (1899) became one of the many references for the pan-Germanic movement of the early twentieth century, and, later, of Nazi racial philosophy.

This philosophy would later be applied by the Nazis in their Final Solution, and while Chamberlain, who died in 1927 prior to the rise to power of Hitler and the Nazis, was not directly responsible for the Holocaust, and did not advocate the destruction of the Jews, his ideas of Aryan supremacy nonetheless were used by the Nazis as justification for those atrocities.

Biography

Houston Stewart Chamberlain was born on September 9 1855, in Southsea, England. His mother, Eliza Jane, daughter of Captain Basil Hall, R.N., died before he was a year old, and he was raised by his grandmother in France.

Chamberlain's education was almost entirely foreign. It began in a Lycée at Versailles, but his father, Rear Admiral William Charles Chamberlain, had planned a military career for his son and at 11 he was sent to Cheltenham College, a public school which produced many future army and navy officers.[1] However, the young Chamberlain was “a compulsive dreamer” more interested in the arts than military discipline, and it was in these formative years that he developed a fondness for nature and a near-mystical sense of self.[2] The prospect of serving as an officer in India or elsewhere in the British Empire held no attraction for him. In addition he was a delicate child, and early health concerns put an end to Chamberlain's military prospects.

At age 14 he suffered from seriously poor health and had to be withdrawn from school. He then traveled to various spas around Europe, accompanied by a Prussian tutor, Herr Otto Kuntze, who taught him German and interested him in German culture and history. Chamberlain then went to Geneva, where under Carl Vogt, (a supporter of racial typology when he taught Chamberlain at the University of Geneva)[3] Graebe, Mueller,[4] Argovensis, Thury, Plantamour, and other professors he studied systematic botany, geology, astronomy, and later the anatomy and physiology of the human body.[5]

Thereafter he migrated to Dresden where "he plunged heart and soul into the mysterious depths of Wagnerian music and philosophy, the metaphysical works of the Master probably exercising as strong an influence upon him as the musical dramas."[6] Chamberlain was immersed in philosophical writings, and became a voelkisch author, one of those who were concerned more with art, culture, civilization and spirit than with quantitative physical distinctions between groups.[7] This is evidenced by his huge treatise on Immanuel Kant. His knowledge of Friedrich Nietzsche is demonstrated in that work (p.183) and Foundations (p.153n). By this time Chamberlain had met his first wife, the Prussian Anna Horst whom he was to divorce in 1905.[8]

In 1889 he moved to Austria. During this time it is said his ideas on race began taking shape, influenced by the Teutonic supremacy embodied in the works of Richard Wagner and Arthur de Gobineau.[9]

Chamberlain had attended Wagner’s Bayreuth Festival in 1882 and struck up a close correspondence with his wife Cosima. In 1908 he married Eva Wagner, the composer’s daughter, and the next year he moved to Germany and became an important member of the "Bayreuth Circle" of German nationalist intellectuals.

By the time World War I broke out in 1914, Chamberlain remained an Englishman only by virtue of his name and nationality. In 1916 he also acquired German citizenship. He had already begun propagandizing on behalf of the German government and continued to do so throughout the war. His vociferous denunciations of his land of birth, it has been posited,[10] were the culmination of his rejection of his native England’s stifling capitalism, in favor of a rustic and ultimately naïve German Romanticism akin to that he had cultivated in himself during his years at Cheltenham. Chamberlain received the Iron Cross from the Kaiser, with whom he was in regular correspondence, in 1916.[11]

After the war Chamberlain’s chronically bad health took a turn for the worse and he was left partially paralyzed; he continued living in Bayreuth until his death in 1927.[12][13]

Writings

Natural science

Under the tutelage of Professor Julius von Wiesner of the University of Vienna, Chamberlain studied botany in Geneva, earning a Bacheliers ès sciences physiques et naturelles in 1881. His thesis Recherches sur la sève ascendante (Studies on rising sap) was not finished until 1897 and did not culminate with a degree.[14] The main thrust of his dissertation is that the vertical transport of fluids in vascular plants via xylem can not be explained by the fluid mechanical theories of the time, but only by the existence of a "vital force" (force vitale) that is beyond the pale of physical measurement. He summarizes his thesis in the Introduction:

| “ | Sans cette participation des fonctions vitales, il est tout simplement impossible que l'eau soit élevée à des hauteurs de 150 pieds, 200 pieds et au delà, et tous les efforts qu'on fait pour cacher les difficultés du problème en se servant de notions confuses tirées de la physique ne sont guère plus raisonnables que la recherche de la pierre philosophale'.'

Without the participation of these vital functions it is quite simply impossible for water to rise to heights of 150 feet, 200 feet and beyond, and all the efforts that one makes to hide the difficulties of the problem by relying on confused notions drawn from physics are little more reasonable than the search for the philosopher's stone.[15] |

” |

Physical arguments, in particular transpirational pull and root pressure have since been shown to adequately explain the ascent of sap.[16]

He was an early supporter of Hans Hörbiger's Welteislehre, the theory that most bodies in our solar system are covered with ice. Due in part to Chamberlain's advocacy, this became official cosmological dogma during the Third Reich.[17]

Chamberlain's attitude towards the natural sciences was somewhat ambivalent and contradictory. He later wrote: "one of the most fatal errors of our time is that which impels us to give too great weight to the so-called 'results' of science."[18] Still, his scientific credentials were often cited by admirers to give weight to his political philosophy.[19]

Richard Wagner

Chamberlain was an admirer of Richard Wagner, and wrote several commentaries on his works including Notes sur Lohengrin (“Notes on Lohengrin”) (1892), an analysis of Wagner's drama (1892), and a biography (1895), emphasizing in particular the heroic Teutonic aspects in the composer's works.[20] One modern critic, Stewart Spencer in Wagner Remembered. (London 2000) has described his edition of Wagner letters as "one of the most egregious attempts in the history of musicology to misrepresent an artist by systematically censoring his correspondence."

Foundations

In 1899 Chamberlain wrote his most important work, Die Grundlagen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts (in German). The work says Western civilization is deeply marked by the influence of Teutonic peoples. Chamberlain grouped all European peoples—not just Germans, but Celts, Slavs, Greeks, and Latins—into the "Aryan race," a race built on the ancient Proto-Indo-European culture. At the helm of the Aryan race, and, indeed, all races, were the Nordic or Teutonic peoples.

The Foundations sold extensively: eight editions and 60,000 copies within ten years, 100,000 copies by the outbreak of World War I and 24 editions and more than a quarter of a million copies by 1938.[21]

Other

During World War I, Chamberlain published several propaganda texts against his country of origin–Kriegsaufsätze (Wartime Essays) In the first four tracts he maintains that Germany is a nation of peace; England’s political system is a sham, while Germany exhibits true freedom; German is the greatest and only remaining “living” language; and the world would be better off doing away with English- and French-styled Parliamentarianism in favor of German rule “thought out by a few and carried out with iron consequence.” The final two discuss England and Germany at length.[22]

Legacy

During his lifetime Chamberlain's works were read widely throughout Europe, and especially in Germany. His reception was particularly favorable among Germany's conservative elite. Kaiser Wilhelm II patronized Chamberlain, maintaining a correspondence, inviting him to stay at his court, distributing copies of Foundations of the Nineteenth Century among the German army, and seeing that Foundations was carried in German libraries and included in the school curricula.[9][23]

Foundations would prove to be a seminal work in German nationalism; due to its success, aided by Chamberlain’s association with the Wagner circle, its ideas of Aryan supremacy and a struggle against Jewish influence spread widely across the German state at the beginning of the century. If it did not form the framework of later National Socialist ideology, at the very least it provided its adherents with a seeming intellectual justification.[24]

Chamberlain himself lived to see his ideas begin to bear fruit. Adolf Hitler, while still growing as a political figure in Germany, visited him several times (in 1923 and in 1926, together with Joseph Goebbels) at the Wagner family’s property in Bayreuth.[23] Chamberlain, paralyzed and despondent after Germany’s losses in World War I, wrote to Hitler after his first visit in 1923:

| “ | Most respected and dear Hitler, … It is hardly surprising that a man like that can give peace to a poor suffering spirit! Especially when he is dedicated to the service of the fatherland. My faith in Germandom has not wavered for a moment, though my hopes were—I confess—at a low ebb. With one stroke you have transformed the state of my soul. That Germany, in the hour of her greatest need, brings forth a Hitler–that is proof of her vitality … that the magnificent Ludendorff openly supports you and your movement: What wonderful confirmation! I can now go untroubled to sleep…. May God protect you![23] | ” |

Chamberlain joined the Nazi Party and contributed to its publications. Their journal Völkischer Beobachter dedicated five columns to praising him on his 70th birthday, describing Foundations as the "gospel of the Nazi movement."[25]

Hitler later attended Chamberlain's funeral in January, 1927 along with several highly ranked members of the Nazi party.[26]

Alfred Rosenberg, who became the Nazi Party's in-house philosopher, was heavily influenced by Chamberlain’s ideas. In 1909, some months before his seventeenth birthday, he went with an aunt to visit his guardian where several other relatives were gathered. Bored, he went to a book shelf, picked up a copy of Chamberlain's Foundations and wrote of the moment "I felt electrified; I wrote down the title and went straight to the bookshop." In 1930 Rosenburg published The Myth of the Twentieth Century, an homage to and continuation of Chamberlain's work.[27] Rosenberg had accompanied Hitler when he called upon Wagner's widow, Cosima, in October 1923 where he met her son-in-law. He told the ailing Chamberlain he was working on his own new book which, he intended, should do for the Third Reich what Chamberlain's book had done for the Second.[28]

Beyond the Kaiser and the Nazi party assessments were mixed. The French Germanic scholar Edmond Vermeil called Chamberlain's ideas "essentially shoddy," but the anti-Nazi German author Konrad Heiden said that Chamberlain "was one of the most astonishing talents in the history of the German mind, a mine of knowledge and profound ideas" despite objections to his racial ideas.[29]

Selected Works

- Notes sur Lohengrin (his first published work), Dresden.

- Das Drama Richard Wagners, 1892.

- Recherches sur La Seve Ascendante, Neuchatel, 1897.

- The Life of Wagner, Munich, 1897, translated into English by G. Ainslie Hight.

- Grundlagen des Neunzehnten Jahrhunderts, 1899.

- Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, translated into English from the German by John Lees, M.A., D.Lit.,(Edinburgh) with an extensive "Introduction" by Lord Redesdale, The Bodley Head, London, 4th English language reprint, 1913, (2 volumes).

- Immanuel Kant - a study and a comparison with Goethe, Leonardo da Vinci, Bruno, Plato and Descartes, the authorized translation into English from the German by Lord Redesdale, with his "Introduction," The Bodley Head, London, 1914, (2 volumes).

- God and Man (his last book).

Notes

- ↑ Lord Redesdale, "Introduction" to Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, 4th English language impression, (London: 1913), vi

- ↑ George L. Mosse, “Introduction to the 1968 Edition.” Foundations of the Nineteenth Century. Chamberlain, Houston Stewart. Vol. I., Translated by John Lees. (New York: Howard Fertig Inc., 1968), ix.

- ↑ A. Bramwell. Blood and Soil - Richard Walther Darré and Hitler's "Green Party". (London, 1985), 206, ISBN 0946041334

- ↑ Probably Max Mueller given his interests in the Aryan race and Kant.

- ↑ Redesdale, vi

- ↑ Redesdale, vi

- ↑ Bramwell, 23 and 40

- ↑ William, L. Shirer The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. (original 1959, Bookclub Associates Edition, 1985), 105.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Allan Chase. The Legacy of Malthus: The Social Costs of the New Scientific Racism. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977), 91-92.

- ↑ Theodor W. Adorno, “On the Question: “What is German?”” translated by Thomas Y. Levin, New German Critique 36 (1985): 123.

- ↑ Shirer, 1985, 108

- ↑ Mosse, xi, xiv.

- ↑ Herrmann A.L. Degener, (ed), Wer Ist's? (the German Who's Who), (Berlin, 1928, vol. 9), 1773 records the death on January 9, 1927, of "Houston Stewart Chamberlain, writer, Bayreuth".

- ↑ J. Powell, D.W. Blakely, and T. Powell. Biographical Dictionary of Literary Influences: The Nineteenth Century. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001), 82-84

- ↑ H.S. Chamberlain. Recherche sur la sève ascendante. (Neuchatel: Attinger Freres, Editeurs, 1897), 8

- ↑ Melvin T. Tyree, Martin H. Zimmermann (2003). Xylem Structure and the Ascent of Sap, 2nd ed. (Springer. ISBN 3540433546 recent update of the classic book on xylem transport by the late Martin Zimmermann)

- ↑ Joachim Herrmann. Das falsche Weltbild. (Stuttgart: Franckhsche Verlagshandlung Kosmos, 1962, in German).

- ↑ Chamberlain. The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century. (London: John Lane, the Bodley Head, 1911), 94 London.

- ↑ Redesdale, vi

- ↑ "Houston Stewart Chamberlain." Encyclopedia Britannica [1]. accessdate 2007-12-22

- ↑ Shirer, 1985, 107

- ↑ Chamberlain, The Ravings of a Renegade: Being the War Essays of Houston Stewart Chamberlain., Translated with a Preface by Charles H. Clark, PhD., and an Introduction by Lewis Melville. (London: Jarrold and Sons, 1915).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 R. Stackelberg, and S.A. Winkle. The Nazi Germany Sourcebook: An Anthology of Texts. (Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0415222133) and online [2], 84-85. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- ↑ Mosse, xvi.

- ↑ Shirer, 1985, 109

- ↑ "Der Todestag des Schriftstellers Houston Stewart Chamberlain," 9 Januar 1927, West Deutsche Rundfunk (in German) 2003-01-01 [3]. accessdate 2007-12-20

- ↑ J.M. Hecht, "Vacher de Lapouge and the Rise of Nazi Science." Journal of the History of Ideas 61 (2): 285-304.

- ↑ Cecil, 12-13

- ↑ Shirer, 1985, 105-106

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adorno, Theodor W. On the Question: “What is German?” trans. Thomas Y. Levin, New German Critique, No. 36. 1985, 123. ISSN 0094-033X

- Bramwell, A., Blood and Soil - Richard Walther Darré and Hitler's "Green Party". London: 1985, 23 and 40, ISBN 0946041334

- Cecil, Robert. The Myth of the Master Race: Alfred Rosenberg and Nazi Ideology. London: Dodd, Mead & Co/Batsford, 1972, 12-13, ISBN 071341121X

- Chamberlain., H.S. (1897). Recherche sur la sève ascendante. Neuchatel: Attinger Freres, Editeurs.

- Chamberlain, H.S. (1911). The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century. London: John Lane, the Bodley Head.

- Chamberlain, H.S. The Ravings of a Renegade: Being the War Essays of Houston Stewart Chamberlain., Translated with a Preface by Charles H. Clark, PhD., and an Introduction by Lewis Melville. London, Jarrold and Sons, 1915.

- Lees, John {Trans}. Foundations of the Nineteenth Century. by Houston Stewart. Chamberlain, Vol. I. New York: Howard Fertig Inc., 1968, ix. OCLC 73056465

- Mosse, George L. “Introduction to the 1968 Edition.” Foundations of the Nineteenth Century. by Chamberlain, Vol. I.

- Powell, J. and D. W. Blakely, T. Powell (2001). Biographical Dictionary of Literary Influences: The Nineteenth Century. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 82-84. ISBN 031330422X

- Shirer, William L. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990. ISBN 9780671728687

- Stackelberg, R. and S.A. Winkle. The Nazi Germany Sourcebook: An Anthology of Texts. Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0415222133. and online [4], 84-85. Retrieved June 4, 2008.

- Tyree, Melvin T. and Martin H. Zimmermann (2003). Xylem Structure and the Ascent of Sap, 2nd ed. Springer. ISBN 3540433546

External Links

All links retrieved January 15, 2018.

- Theodore Roosevelt's review of The Foundations of the 19th Century

- Houston Stewart Chamberlain biography and transcriptions - online compendium arranged by an admirer.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.