Helen Keller

| Helen Adams Keller |

|---|

Deaf-blind American author, activist, and lecturer

|

| Born |

| June 27, 1880 Tuscumbia, Alabama, USA |

| Died |

| June 1, 1968 Easton, Connecticut, USA |

Helen Adams Keller (June 27, 1880 - June 1, 1968) was an American author, activist, and lecturer. Both deaf and blind, she changed the public's perception of people with disabilities. She became known around the world as a symbol of the indomitable human spirit, yet she was much more than a symbol. She was a woman of luminous intelligence, high ambition, and great accomplishment, having devoted her life to helping others. Helen Keller was an impassioned advocate for the rights of people with disabilities. She played a leading role in most of the significant political, social, and cultural movements of the twentieth century.

Her life story exemplifies well the truth that though the body's physical limitations may constrain one's performance, a person's true value comes from the height and depth of her mind.

Childhood

Helen Keller was born at an estate called Ivy Green in Tuscumbia, Alabama, on June 27, 1880, to parents Captain Arthur H. Keller and Kate Adams Keller. She was not born blind or deaf; it was not until nineteen months of age that she came down with an illness described by doctors as "an acute congestion of the stomach and the brain," which could have possibly been scarlet fever or meningitis. The illness did not last for a particularly long time, but it left her deaf and blind. By age seven she had invented over sixty different hand signals that she could use to communicate with her family.

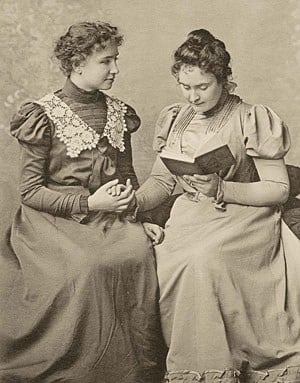

In 1886, her mother Kate Keller was inspired by an account in Charles Dickens' American Notes of the successful education of another deaf/blind child, Laura Bridgman, and traveled to a specialist doctor in Baltimore, Maryland for advice. He connected her with local expert Alexander Graham Bell, who was working with deaf children at the time. Bell advised the couple to contact the Perkins Institute for the Blind, the school where Bridgman had been educated, which was then located in Boston, Massachusetts. The school delegated teacher and former student, Anne Sullivan, herself visually impaired and then only 20 years old, to become Helen's teacher. It was the beginning of a 49-year-long relationship.

Sullivan obtained permission from Helen's father to isolate the girl from the rest of the family in a little house in their garden. Her first task was to instill discipline in the spoiled girl. Helen's big breakthrough in communication came one day when she realized that the motions her teacher was making on her palm, while running cool water over her palm from a pump, symbolized the idea of "water"; she then nearly exhausted Sullivan demanding the names of all the other familiar objects in her world (including Helen's prized doll).

In 1890, ten-year-old Helen Keller was introduced to the story of Ragnhild Kåta—a deaf/blind Norwegian girl who had learned to speak. Ragnhild Kåta's success inspired Helen—she wanted to learn to speak as well. Anne was able to teach Helen to speak using the Tadoma method (touching the lips and throat of others as they speak) combined with "fingerspelling" alphabetical characters on the palm of Helen's hand. Later, Keller would also learn to read English, French, German, Greek, and Latin in Braille.

Education

In 1888, Helen attended the Perkins School for the Blind. At age eleven, in 1891, Helen wrote to her father:

I cannot believe that parents would keep their deaf or blind children at home to grow up in silence and darkness if they knew there was a good school at Talladega where they would be kindly and wisely treated. Little deaf and blind children love to learn…and God means that they shall be taught. He has given them minds that can understand and hands with sensitive fingertips that are almost as good as eyes. I cannot see or hear, and yet I have been taught to do nearly everything that other girls do. I am happy all the day long because education has brought light and music to my soul….[1]

In 1894, Helen and Anne moved to New York City to attend the Wright-Humason School for the Deaf. In 1898, they returned to Massachusetts and Helen entered The Cambridge School for Young Ladies before gaining admittance, in 1900, to Radcliffe College. In 1904, at the age of 24, Helen graduated from Radcliffe magna cum laude, becoming the first deaf and blind person to earn a Bachelor's degree.

Helen Keller became closely associated with Alexander Graham Bell because he too was working with deaf people. Bell was passionate in his belief that people who were deaf must learn to speak in order to become a part of the hearing community. Helen took many lessons in elocution and speech, but unfortunately, she could never master oral communications to her satisfaction. If Helen Keller had been born a hundred years later, her life would have been totally different since teaching methods developed that would have helped her realize her dream of speaking.

Touring the World

Helen Keller's speech handicap did not stop her as she went on to become a world-famous "speaker" and author. On her speaking tours, she traveled with Anne Sullivan Macy who introduced Helen Keller and interpreted her remarks to the audience. Keller is remembered as an advocate for the disabled, as well as numerous causes. She was a suffragette, a pacifist and a supporter of birth control. In 1915, she founded Helen Keller International, a non-profit organization for preventing blindness and she "spoke" at fundraising activities throughout the country. Helen traveled not only to educate the public about deafblindness but also to earn a living.

Helen’s mother Kate died in 1921, from an unknown illness, and in that same year Anne fell ill. By 1922, Anne was unable to work with Helen on stage anymore, and Polly Thomson, a secretary for Helen and Anne since 1914, became Helen's assistant on her public tours. They visited Japan, Australia, South America, Europe, and Africa fundraising for the American Foundation for the Overseas Blind (now Helen Keller International).

Helen Keller traveled the world over to different 39 countries, and made several trips to Japan, becoming a favorite of the Japanese people. She met every U.S. President from Grover Cleveland to Lyndon B. Johnson and was friends with many famous figures including Alexander Graham Bell, Charlie Chaplin and Mark Twain.

Introduction of the Akita dog to America

When Keller visited Akita Prefecture in Japan in July 1937, she inquired about Hachiko, the famed Akita dog that had died in 1935. She expressed to a local that she would like to have an Akita dog. An Akita called Kamikaze-go was given to her within a month. When Kamikaze-go later died (at a young age) because of canine distemper, his older brother, Kenzan-go, was presented to her as an official gift from the Japanese government in July 1939.

Keller is credited with having introduced the Akita to America through Kamikaze-go and his successor, Kenzan-go. By 1938, a breed standard had been established and dog shows had been held, but such activities stopped after World War II began.

Keller wrote in the Akita Journal:

"If ever there was an angel in fur, it was Kamikaze. I know I shall never feel quite the same tenderness for any other pet. The Akita dog has all the qualities that appeal to me—he is gentle, companionable and trusty."[2][3]

Political Activities

Helen Keller was a member of the United States Socialist Party and actively campaigned and wrote in support of the working classes from 1909 to 1921. She supported Socialist Party candidate Eugene V. Debs in each of his campaigns for the presidency. Her political views were reinforced by visiting workers. In her words, "I have visited sweatshops, factories, crowded slums. If I could not see it, I could smell it."

Helen Keller also joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) labor union in 1912, after she felt that parliamentary socialism was "sinking in the political bog." Helen Keller wrote for the IWW between 1916 and 1918. In "Why I Became an IWW," she wrote that her motivation for activism came in part due to her concern about blindness and other disabilities:

I was religious to start with. I had thought blindness a misfortune. Then I was appointed on a commission to investigate the conditions among the blind. For the first time I, who had thought blindness a misfortune beyond human control, found that too much of it was traceable to wrong industrial conditions, often caused by the selfishness and greed of employers. And the social evil contributed its share. I found that poverty drove women to the life of shame that ended in blindness.

Then I read H.G. Wells' Old Worlds for New, summaries of Karl Marx's philosophy and his manifestoes. It seemed as if I had been asleep and waked to a new world—a world so different from the beautiful world I had lived in. For a time I was depressed but little by little my confidence came back and I realized that the wonder is not that conditions are so bad, but that humanity has advanced so far in spite of them. And now I am in the fight to change things. I may be a dreamer, but dreamers are necessary to make facts!

I feel like Joan of Arc at times. My whole becomes uplifted. I, too, hear the voices that say 'Come,' and I will follow, no matter what the cost, no matter what the trials I am placed under. Jail, poverty, and calumny; they matter not. Truly He has said, "Woe unto you that permits the least of mine to suffer."

Writings, Honors, and Later Life

In 1960, her book Light in my Darkness was published in which she advocated the teachings of the Swedish scientist, philosopher, and explorer of spiritual realms, Emanuel Swedenborg. She also wrote a lengthy autobiography called The Story of My Life published in 1903. This was the most popular of her works and is now available in more than 50 languages.

She wrote a total of eleven books, and authored numerous articles. Her published works include Optimism, an essay; The World I Live In; The Song of the Stone Wall; Out of the Dark; My Religion; Midstream—My Later Life; Peace at Eventide; Helen Keller in Scotland; Helen Keller's Journal; Let Us Have Faith; Teacher, Anne Sullivan Macy; and The Open Door.

On September 14, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded Helen Keller the Presidential Medal of Freedom, one of the United States' top two highest civilian honors. In 1965, she was one of 20 elected to the Women's Hall of Fame at the New York World's Fair. Helen Keller is now honored in The Hall of Fame for Leaders and Legends of the Blindness Field.

Keller devoted much of her later life to raising funds for the American Foundation for the Blind. She died on June 1, 1968, passing away 26 days before her 88th birthday, in her Easton, Connecticut home. At her funeral, Senator Lister Hill eulogized, "She will live on, one of the few, immortal names not born to die. Her spirit will endure as long as man can read and stories can be told of the woman who showed the world there are no boundaries to courage and faith."

Helen Keller received so many awards of great distinction, an entire room, called the Helen Keller Archives at the American Foundation for the Blind in New York City, is devoted to their preservation.

In 2003, the state of Alabama honored Keller—a native of the state—on its state quarter. The Helen Keller Hospital is also dedicated to her.

Portrayals of Helen Keller

A silent film, Deliverance (1919 movie) (not to be mistaken for the other, much later and more famous movie Deliverance which is unrelated to Keller) first told Keller's story.[4] The Miracle Worker, a play about how Helen Keller learned to communicate, was made into a movie three times. The 1962, The Miracle Worker version of the movie won Academy Awards for Best Actress in a Leading Role for Anne Bancroft who played Sullivan and Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in a Supporting Role for Patty Duke who played Keller.[5] It also became a 1979 television movie, with Patty Duke playing Anne Sullivan and Melissa Gilbert playing Helen Keller,[6] as well as a 2000 television movie.[7]

The 1984 television movie about Helen Keller's life is The Miracle Continues.[8] This semi-sequel to The Miracle Worker recounts her college years and her early adult life. None of the early movies hint at the social activism that would become the hallmark of Helen's later life, although the Walt Disney Company version produced in 2000 states in the credits that Helen became an activist for social equality.

The Hindi movie Black (2005) released in 2005 was largely based on Keller's story, from her childhood to her graduation.

A documentary Shining Soul: Helen Keller's Spiritual Life and Legacy was produced and released by The Swedenborg Foundation in 2005. The film focuses on the role played by Emanuel Swedenborg's spiritual theology in her life and how it inspired Keller's triumph over her triple disabilities of blindness, deafness, and a severe speech impediment.

Countries Helen Keller Visited

Australia - 1948

Brazil - 1953

Burma (now called Myanmar) - 1955

Canada - 1901, 1957

Chile - 1953

China - Manchuria in 1937, and Hong Kong in 1955

Denmark - 1957

Egypt - 1952

Finland - 1957

France - 1931, 1946, 1950, 1952

Germany - 1956

Great Britain - 1930, 1932, 1946, 1951, 1953

Greece - 1946

Iceland - 1957

India - 1955

Indonesia - 1955

Ireland - 1930

Israel - 1952

Italy - 1946, 1956

Japan - 1937, 1948, 1955

Jordan - 1952

Korea - 1948

Lebanon - 1952

Mexico - 1953

New Zealand - 1948

Norway - 1957

Pakistan - 1955

Panama - 1953

Peru - 1953

Philippines - 1948, 1953

Portugal - 1956

Scotland - 1932, 1934, 1955

South Africa - 1951

Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) - 1951

Spain - 1956

Sweden - 1957

Switzerland - 1957

Syria - 1952

Yugoslavia - 1931

Notes

- ↑ Helen Keller Biography, Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- ↑ The Akita Inu: The Voice of Japan, Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- ↑ First Akitas in the USA, Retrieved October 26, 2007.

- ↑ Deliverance (1919). Retrieved June 15, 2006.

- ↑ The Miracle Worker (1962). Retrieved June 15, 2006.

- ↑ The Miracle Worker (1979) TV. Retrieved June 15, 2006.

- ↑ The Miracle Worker (2000) TV. Retrieved June 15, 2006.

- ↑ Helen Keller: The Miracle Continues (1984) (TV). Retrieved June 15, 2006.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Herrmann, Dorothy. Helen Keller. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0226327631

- Keller, Helen. The world I live in. Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1177620635

- Keller, Helen. The Story Of My Life. Signet Classics; Reprint edition, 2010. ISBN 978-0451531568

- Lash, Joseph P. Helen And Teacher: The Story Of Helen Keller And Anne Sullivan Macy. Da Capo Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0201694680

External links

All links retrieved December 13, 2017.

- American Foundation for the Blind's Helen Keller collection

- Helen Keller Kids Museum Online

- The Story of My Life with introduction to the text

- Official site of Ivy Green, Helen Keller's birthplace

- The Helen Keller Services for the blind

- The Socialist Legacy of Helen Keller.

- New York Times Obituary

- Review of the Documentary Shining Soul: Helen Keller's Spiritual Life and Legacy

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.