Gregorian chant is the central tradition of Western plainsong or plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song of the Roman Catholic Church. The Gregorian chant had as its purpose the praise and service of God. The purity of the melodic lines fostered in the listener a singular focus on divine, without humanistic distractions.

Gregorian chant developed mainly in the Frankish lands of western and central Europe during the ninth and tenth centuries, with later additions and redactions. Although popular legend credits Pope Gregory I (the Great) with inventing Gregorian chant, scholars believe that it arose from a later Carolingian synthesis of Roman and Gallican chant.

Gregorian chants are organized into eight scalar musical modes. Typical melodic features include characteristic incipits and cadences, the use of reciting tones around which the other notes of the melody revolve, and a vocabulary of musical motifs woven together through a process called 'centonization' to create families of related chants. Instead of octave scales, six-note patterns called hexachords came to define the modes. These patterns use elements of the modern diatonic scale as well as what would now be called B flat. Gregorian melodies are transcribed using 'neumes', an early form of musical notation from which the modern five-line staff developed during the sixteenth century.[1] Gregorian chant played a fundamental role in the development of polyphony.

Gregorian chant was traditionally sung by choirs of men and boys in churches, or by women and men of religious orders in their chapels. Gregorian chant supplanted or marginalized the other indigenous plainchant traditions of the Christian West to become the official music of the Roman Catholic liturgy. Although Gregorian chant is no longer obligatory, the Roman Catholic Church still officially considers it the music most suitable for worship.[2] During the twentieth century, Gregorian chant underwent a musicological and popular resurgence.

History

Development of earlier plainchant

Unaccompanied singing has been part of the Christian liturgy since the earliest days of the Church. Until the mid-1990s, it was widely accepted that the psalms of ancient Israel and Jewish worship significantly influenced and contributed to early Christian ritual and chant. This view is no longer generally accepted by scholars, due to analysis that shows that most early Christian hymns did not have Psalms for texts, and that the Psalms were not sung in synagogues for centuries after the Siege of Jerusalem (70) and Destruction of the Second Temple in AD 70.[3] However, early Christian rites did incorporate elements of Jewish worship that survived in later chant tradition. Canonical hours have their roots in Jewish prayer hours. "Amen" and "alleluia" come from the Hebrew language, and the threefold "sanctus" derives from the threefold "kadosh" of the Kedusha.[4]

The New Testament mentions singing hymns during the Last Supper: "When they had sung the hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives" Matthew 26.30. Other ancient witnesses such as Pope Clement I, Tertullian, Athanasius of Alexandria or St. Athanasius, and Egeria (pilgrim) confirm the practice,[5] although in poetic or obscure ways that shed little light on how music sounded during this period.[6][7] The third-century Greek "Oxyrhynchus hymn" survived with musical notation, but the connection between this hymn and the plainchant tradition is uncertain.[8]

Musical elements that would later be used in the Roman Rite began to appear in the third century. The Apostolic Tradition, attributed to the theologian and writer, Hippolytus, attests the singing of 'Hallel' psalms with Alleluia as the refrain in early Christian agape feasts.[9] Chants of the Office, sung during the canonical hours, have their roots in the early fourth century, when desert monks following Saint Anthony introduced the practice of continuous psalmody, singing the complete cycle of 150 psalms each week. Around 375, antiphonal psalmody became popular in the Christian East; in 386, Saint Ambrose introduced this practice to the West.

Scholars are still debating how plainchant developed during the fifth through the ninth centuries, as information from this period is scarce. Around 410, Augustine of Hippo or Saint Augustine described the responsorial singing of a Gradual psalm at Mass. Around 678 C.E., Roman chant was taught at York.[10] Distinctive regional traditions of Western plainchant arose during this period, notably in the British Isles (Celtic chant), Spain (Mozarabic chant), Gaul (Gallican chant), and Italy (Old Roman Chant, Ambrosian chant and Beneventan chant). These traditions may have evolved from a hypothetical year-round repertory of fifth-century plainchant after the western Roman Empire collapsed.

Origins of the new tradition

The Gregorian repertory was systematized for use in the Roman Rite. According to James McKinnon, the core liturgy of the Roman Mass was compiled over a brief period in the late seventh century. Other scholars, including Andreas Pfisterer and Peter Jeffery, have argued for an earlier origin for the oldest layers of the repertory.

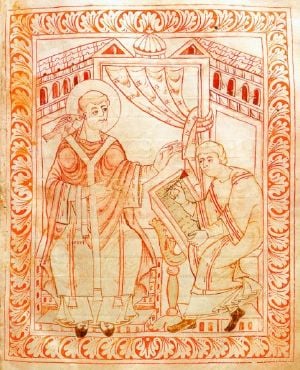

Scholars debate whether the essentials of the melodies originated in Rome, before the seventh century, or in Francia, in the eighth and early ninth centuries. Traditionalists point to evidence supporting an important role for Pope Gregory I (Gregory the Great) between 590 and 604, such as that presented in H. Bewerung's article in the Catholic Encyclopedia.[11] Scholarly consensus, supported by Willi Apel and Robert Snow, asserts instead that Gregorian chant developed around 750 from a synthesis of Roman and Gallican chant commissioned by Carolingian rulers in France. During a visit to Gaul in 752-753, Pope Stephen II had celebrated Mass using Roman chant. According to Charlemagne, his father Pepin abolished the local Gallican rites in favor of the Roman use, in order to strengthen ties with Rome.[12] In 785-786, at Charlemagne's request, Pope Hadrian I sent a papal sacramentary with Roman chants to the Carolingian court. This Roman chant was subsequently modified, influenced by local styles and Gallican chant, and later adapted into the system of eight musical modes. This Frankish-Roman Carolingian chant, augmented with new chants to complete the liturgical year, became known as "Gregorian." Originally the chant was probably so named to honor the contemporary Pope Gregory II,[13] but later lore attributed the authorship of chant to his more famous predecessor Gregory the Great. Gregory was portrayed dictating plainchant inspired by a dove representing the Holy Spirit, giving Gregorian chant the stamp of holy authority. Gregory's authorship is popularly accepted as fact to this day.[14]

Dissemination and hegemony

Gregorian chant appeared in a remarkably uniform state across Europe within a short time. Charlemagne, once elevated as the Holy Roman Emperor, aggressively spread Gregorian chant throughout his empire to consolidate religious and secular power, requiring the clergy to use the new repertory on pain of death.[15] From English and German sources, Gregorian chant spread north to Scandinavia, Iceland and Finland.[16] In 885, Pope Stephen V banned the Church Slavonic language liturgy, leading to the ascendancy of Gregorian chant in Eastern Catholic lands including Poland, Moravia, Slovakia, and Austria.

The other plainchant repertories of the Christian West faced severe competition from the new Gregorian chant. Charlemagne continued his father's policy of favoring the Roman Rite over the local Gallican traditions. By the ninth century the Gallican rite and chant had effectively been eliminated, although not without local resistance.[17] The Gregorian chant of the Sarum Rite displaced Celtic chant. Gregorian coexisted with Beneventan chant for over a century before Beneventan chant was abolished by papal decree (1058). Mozarabic chant survived the influx of the Visigoths and Moors, but not the Roman-backed prelates newly installed in Spain during the Reconquista period. Restricted to a handful of dedicated chapels, modern Mozarabic chant is highly Gregorianized and bears no musical resemblance to its original form. Ambrosian chant alone survived to the present day, preserved in Milan due to the musical reputation and ecclesiastical authority of Saint Ambrose.

Gregorian chant eventually replaced the local chant tradition of Rome itself, which is now known as Old Roman chant. In the tenth century, virtually no musical manuscripts were being notated in Italy. Instead, Roman Popes imported Gregorian chant from the German Holy Roman Emperors during the tenth and eleventh centuries. For example, the Credo was added to the Roman Rite at the behest of the German emperor Henry II of Germany in 1014.[18] Reinforced by the legend of Pope Gregory, Gregorian chant was taken to be the authentic, original chant of Rome, a misconception that continues to this day. By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Gregorian chant had supplanted or marginalized all the other Western plainchant traditions.

Later sources of these other chant traditions show an increasing Gregorian influence, such as occasional efforts to categorize their chants into the Gregorian musical modes. Similarly, the Gregorian repertory incorporated elements of these lost plainchant traditions, which can be identified by careful stylistic and historical analysis. For example, the Improperia of Good Friday are believed to be a remnant of the Gallican repertory.[19]

Early sources and later revisions

The first extant sources with musical notation were written in the later ninth century. Before this, plainchant had been transmitted orally. Most scholars of Gregorian chant agree that the development of music notation assisted the dissemination of chant across Europe. The earlier notated manuscripts are primarily from Regensburg in Germany, Abbey of Saint Gall in Switzerland, and Laon and Abbey of Saint Martial in France.

Gregorian chant has undergone a series of redactions, usually in the name of restoring the allegedly corrupted chant to a hypothetical "original" state. Early Gregorian chant was revised to conform to the theoretical structure of the musical modes. In 1562–63, the Council of Trent banned most poetic sequences. Guidette's Directorium chori, published in 1582, and the Editio medicaea, published in 1614, drastically revised what was perceived as corrupt and flawed "barbarism" by making the chants conform to contemporary aesthetic standards.[20] In 1811, the French musicologist Alexandre-Étienne Choron, as part of a conservative backlash following the liberal Catholic orders' inefficacy during the French Revolution, called for returning to the "purer" Gregorian chant of Rome over French corruptions.[21]

In the late nineteenth century, early liturgical and musical manuscripts were unearthed and edited. In 1871, the Medicean edition of Gregorian chant was reprinted, which Pope Pius IX declared the only official version. In 1889, the monks of Abbey Saint-Pierre de Solesmes released a competing edition, the Paléographie musicale, which sought to present the original medieval melodies. This reconstructed chant was academically praised, but rejected by Rome until 1903, when Pope Leo XIII died. His successor, Pope Pius X, promptly accepted the Solesmes chant—now compiled as the Liber usualis—as authoritative. In 1904, the Vatican edition of the Solesmes chant was commissioned. Serious academic debates arose, primarily owing to stylistic liberties taken by the Solesmes editors to impose their controversial interpretation of rhythm. The Solesmes editions insert phrasing marks and note-lengthening episema and mora marks not found in the original sources. Conversely, they omit significative letters found in the original sources, which give instructions for rhythm and articulation such as speeding up or slowing down. This editorializing has placed the historical authenticity of the Solesmes interpretation in doubt.[22]

In his motu proprio Tra le sollicitudine, Pius X mandated the use of Gregorian chant, encouraging the faithful to sing the Ordinary of the Mass, although he reserved the singing of the Propers for males. While this custom is maintained in traditionalist Catholic communities, the Catholic Church no longer persists with this ban. Vatican II officially allowed worshipers to substitute other music, particularly modern music in the vernacular, in place of Gregorian chant, although it did reaffirm that Gregorian chant was still the official music of the Catholic Church, and the music most suitable for worship.[23]

Musical form

Melodic types

Gregorian chants are categorized into three melodic types based on the number of pitches sung to each syllable. Syllabic chants have primarily one note per syllable. In neumatic chants, two or three notes per syllable predominate, while melismatic chants have syllables that are sung to a long series of notes, ranging from five or six notes per syllable to over sixty in the more prolix melismas.[24]

Gregorian chants fall into two broad categories of melody: recitatives and free melodies.[25] The simplest kind of melody is the liturgical recitative. Recitative melodies are dominated by a single pitch, called the reciting tone. Other pitches appear in melodic formulae for incipits, partial cadences, and full cadences. These chants are primarily syllabic. For example, the Collect for Easter consists of 127 syllables sung to 131 pitches, with 108 of these pitches being the reciting note A and the other 23 pitches flexing down to G.[26] Liturgical recitatives are commonly found in the accentus chants of the liturgy, such as the intonations of the Collect, Epistle, and Gospel during the Mass, and in the direct psalmody of the Canonical hours of the Office Psalmodic chants, which intone psalms, include both recitatives and free melodies. Psalmodic chants include direct psalmody, antiphonal chants, and responsorial chants.[27] In direct psalmody, psalm verses are sung without refrains to simple, formulaic tones. Most psalmodic chants are antiphonal and responsorial, sung to free melodies of varying complexity.

Antiphonal chants such as the Introit, and Communion originally referred to chants in which two choirs sang in alternation, one choir singing verses of a psalm, the other singing a refrain called an antiphon. Over time, the verses were reduced in number, usually to just one psalm verse and the Doxology, or even omitted entirely. Antiphonal chants reflect their ancient origins as elaborate recitatives through the reciting tones in their melodies. Ordinary chants, such as the Kyrie and Gloria, are not considered antiphonal chants, although they are often performed in antiphonal style Responsorial chants such as the Gradual, Tract, Alleluia, Offertory, and the Office Responsories originally consisted of a refrain called a respond sung by a choir, alternating with psalm verses sung by a soloist. Responsorial chants are often composed of an amalgamation of various stock musical phrases, pieced together in a practice called centonization. Although the Tracts lost their responds, they are strongly centonized. Gregorian chant evolved to fulfill various functions in the Roman Catholic liturgy. Broadly speaking, liturgical recitatives are used for texts intoned by deacons or priests. Antiphonal chants accompany liturgical actions: the entrance of the officiant, the collection of offerings, and the distribution of sanctified bread and wine. Responsorial chants expand on readings and lessons.[28]

The non-psalmodic chants, including the Ordinary of the Mass, sequences, and hymns, were originally intended for congregational singing.[29] The structure of their texts largely defines their musical style. In sequences, the same melodic phrase is repeated in each couplet. The strophic texts of hymns use the same syllabic melody for each stanza.

Modality

Early plainchant, like much of Western music, is believed to have been distinguished by the use of the diatonic scale. Modal theory, which postdates the composition of the core chant repertory, arises from a synthesis of two very different traditions: the speculative tradition of numerical ratios and species inherited from ancient Greece and a second tradition rooted in the practical art of cantus. The earliest writings that deal with both theory and practice include the 'Enchiriadis' group of treatises, which circulated in the late ninth century and possibly have their roots in an earlier, oral tradition. In contrast to the ancient Greek system of tetrachords (a collection of four continuous notes) that descend by two tones and a semitone, the Enchiriadis writings base their tone-system on a tetrachord that corresponds to the four finals of chant, D, E, F, and G. The disjunct tetrachords in the Enchiriadis system have been the subject of much speculation, because they do not correspond to the diatonic framework that became the standard Medieval scale (for example, there is a high f#, a note not recognized by later Medieval writers). A diatonic scale with a chromatically alterable b/b-flat was first described by Hucbald, who adopted the tetrachord of the finals (D,E,F,G) and constructed the rest of the system following the model of the Greek Greater and Lesser Perfect Systems. These were the first steps in forging a theoretical tradition that corresponded to chant.

Around 1025, Guido d'Arezzo revolutionized Western music with the development of the gamut, in which pitches in the singing range were organized into overlapping hexachords. Hexachords could be built on C (the natural hexachord, C-D-E^F-G-A), F (the soft hexachord, using a B-flat, F-G-A^Bb-C-D), or G (the hard hexachord, using a B-natural, G-A-B^C-D-E). The B-flat was an integral part of the system of hexachords rather than a musical accidental. The use of notes outside of this collection was described as 'musica ficta'.

Gregorian chant was categorized into eight musical modes, influenced by the eightfold division of Byzantine chants called the oktoechos.[30] Each mode is distinguished by its final, dominant, and ambitus. The final is the ending note, which is usually an important note in the overall structure of the melody. The dominant is a secondary pitch that usually serves as a reciting tone in the melody. Ambitus refers to the range of pitches used in the melody. Melodies whose final is in the middle of the ambitus, or which have only a limited ambitus, are categorized as plagal, while melodies whose final is in the lower end of the ambitus and have a range of over five or six notes are categorized as authentic. Although corresponding plagal and authentic modes have the same final, they have different dominants.[31] The names, rarely used in medieval times, derive from a misunderstanding of the Ancient Greek modes; the prefix "Hypo-" indicates corresponding plagal modes.

- Modes 1 and 2 are the authentic and plagal modes ending on D, sometimes called Dorian mode and Hypodorian mode.

- Modes 3 and 4 are the authentic and plagal modes ending on E, sometimes called Phrygian mode and Hypophrygian mode.

- Modes 5 and 6 are the authentic and plagal modes ending on F, sometimes called Lydian mode and Hypolydian mode.

- Modes 7 and 8 are the authentic and plagal modes ending on G, sometimes called Mixolydian mode and Hypomixolydian mode.

Although the modes with melodies ending on A, B, and C are sometimes referred to as Aeolian mode, Locrian mode, and Ionian mode, these are not considered distinct modes and are treated as transpositions of whichever mode uses the same set of hexachords. The actual pitch of the Gregorian chant is not fixed, so the piece can be sung in whichever range is most comfortable.

Certain classes of Gregorian chant have a separate musical formula for each mode, allowing one section of the chant to transition smoothly into the next section, such as the psalm tones between antiphons and psalm verses.[32]

Not every Gregorian chant fits neatly into Guido's hexachords or into the system of eight modes. For example, there are chants—especially from German sources—whose neumes suggest a warbling of pitches between the notes E and F, outside the hexachord system.[33] Early Gregorian chant, like Ambrosian chant and Old Roman chant, whose melodies are most closely related to Gregorian, did not use the modal system.[34] As the modal system gained acceptance, Gregorian chants were edited to conform to the modes, especially during twelfth-century Cistercian reforms. Finals were altered, melodic ranges reduced, melismas trimmed, B-flats eliminated, and repeated words removed.[35] Despite these attempts to impose modal consistency, some chants—notably Communions—defy simple modal assignment. For example, in four medieval manuscripts, the Communion Circuibo was transcribed using a different mode in each.[36]

Musical idiom

Several features besides modality contribute to the musical idiom of Gregorian chant, giving it a distinctive musical flavor. Melodic motion is primarily steps and skips or a stepwise motion. Skips of a third are common, and larger skips far more common than in other plainchant repertories such as Ambrosian chant or Beneventan chant. Gregorian melodies are more likely to traverse a seventh than a full octave, so that melodies rarely travel from D up to the D an octave higher, but often travel from D to the C a seventh higher, using such patterns as D-F-G-A-C.[37] Gregorian melodies often explore chains of pitches, such as F-A-C, around which the other notes of the chant gravitate.[38] Within each mode, certain incipits and cadences are preferred, which the modal theory alone does not explain. Chants often display complex internal structures that combine and repeat musical subphrases. This occurs notably in the Offertories; in chants with shorter, repeating texts such as the Kyrie and Agnus Dei; and in longer chants with clear textual divisions such as the Great Responsories, the Gloria in excelsis Deo, and the Credo.[39]

Chants sometimes fall into melodically related groups. The musical phrases centonized to create Graduals and Tracts follow a musical "grammar" of sorts. Certain phrases are used only at the beginnings of chants, or only at the end, or only in certain combinations, creating musical families of chants such as the Iustus ut palma family of Graduals.[40] Several Introits in mode 3, including Loquetur Dominus above, exhibit melodic similarities. Mode 3 chants have C as a dominant, so C is the expected reciting tone. These mode 3 Introits, however, use both G and C as reciting tones, and often begin with a decorated leap from G to C to establish this tonality.[41] Similar examples exist throughout the repertory.

Notation

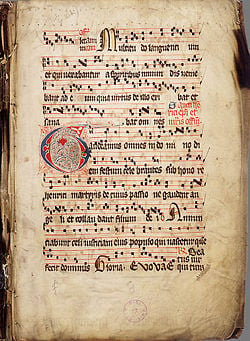

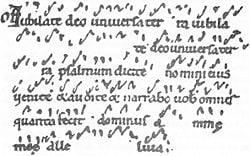

The earliest notated sources of Gregorian chant used symbols called neumes to indicate changes in pitch and duration within each syllable, but not the specific pitches of individual notes, nor the relative starting pitches of each neume. Scholars postulate that this practice may have been derived from cheironomic hand-gestures, the ekphonetic notation of Byzantine chant, punctuation marks, or diacritical accents.[42] Later innovations included the use of heightened or diastemic neumes showing the relative pitches between neumes. Consistent relative heightening first developed in the Aquitaine region, particularly at St. Martial de Limoges, in the first half of the eleventh century. Many German-speaking areas, however, continued to use unpitched neumes into the twelfth century. Other innovations included a musical staff marking one line with a particular pitch, usually C or F. Additional symbols developed, such as the custos, placed at the end of a system to show the next pitch. Other symbols indicated changes in articulation, duration, or tempo, such as a letter "t" to indicate a 'tenuto'. Another form of early notation used a system of letters corresponding to different pitches, much as Shaker music is notated.

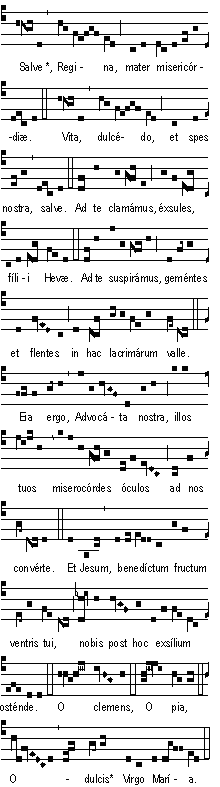

By the thirteenth century, the neumes of Gregorian chant were usually written in square notation on a four-line staff with a clef, as in the Graduale Aboense pictured above. In square notation, small groups of ascending notes on a syllable are shown as stacked squares, read from bottom to top, while descending notes are written with diamonds read from left to right. When a syllable has a large number of notes, a series of smaller such groups of neumes are written in succession, read from left to right. The oriscus, quilisma, and liquescent neumes indicate special vocal treatments, whose exact nature is unconfirmed. B-flat is indicated by a "soft b" placed to the left of the entire neume in which the note occurs, as shown in the "Kyrie" to the right. When necessary, a "hard b" with a descender indicates B-natural. This system of square notation is standard in modern chantbooks.

Performance

Texture

Chant was traditionally reserved for men, as it was originally sung by the all-male clergy during the Mass and the prayers of the Canonical Hours or Office. Outside the larger cities, the number of available clergy dropped, and lay men started singing these parts. In convents, women were permitted to sing the Mass and Office as a function of their consecrated life, but the choir was still considered an official liturgical duty reserved to clergy, so lay women were not allowed to sing in the Schola cantorum or other choirs.[43]

Chant was normally sung in unison. Later innovations included tropes, extra words or notes added to a chant, and organum, improvisational harmonies focusing on octaves, fifths, fourths, and, later, thirds. Neither tropes nor organum, however, belong to the chant repertory proper. The main exception to this is the sequence, whose origins lay in troping the extended melisma of Alleluia chants known as the jubilus, but the sequences, like the tropes, were later officially suppressed. The Council of Trent struck sequences from the Gregorian corpus, except those for Easter, Pentecost, Corpus Christi and All Souls' Day.

We do not know much about the particular vocal stylings or performance practices used for Gregorian chant in the Middle Ages. On occasion, the clergy was urged to have their singers perform with more restraint and piety. This suggests that virtuosic performances occurred, contrary to the modern stereotype of Gregorian chant as slow-moving mood music. This tension between musicality and piety goes far back; Pope Gregory I (Gregory the Great) himself criticized the practice of promoting clerics based on their charming singing rather than their preaching.[44] However, Odo of Cluny, a renowned monastic reformer, praised the intellectual and musical virtuosity to be found in chant:

"For in these [Offertories and Communions] there are the most varied kinds of ascent, descent, repeat …, delight for the cognoscenti, difficulty for the beginners, and an admirable organization … that widely differs from other chants; they are not so much made according to the rules of music … but rather evince the authority and validity … of music."[45]

True antiphonal performance by two alternating choruses still occurs, as in certain German monasteries. However, antiphonal chants are generally performed in responsorial style by a solo cantor alternating with a chorus. This practice appears to have begun in the Middle Ages.[46] Another medieval innovation had the solo cantor sing the opening words of responsorial chants, with the full chorus finishing the end of the opening phrase. This innovation allowed the soloist to fix the pitch of the chant for the chorus and to cue the choral entrance.

Rhythm

Because of the ambiguity of medieval notation, rhythm in Gregorian chant is contested among scholars. Certain neumes such as the pressus indicate repeated notes, which may indicate lengthening or repercussion. By the thirteenth century, with the widespread use of square notation, most chant was sung with an approximately equal duration allotted to each note, although Jerome of Moravia cites exceptions in which certain notes, such as the final notes of a chant, are lengthened.[47] Later redactions such as the Editio medicaea of 1614 rewrote chant so that melismas, with their melodic accent, fell on accented syllables.[48] This aesthetic held sway until the re-examination of chant in the late nineteenth century by such scholars as Wagner, Pothier, and Mocquereau, who fell into two camps.

One school of thought, including Wagner, Jammers, and Lipphardt, advocated imposing rhythmic meters on chants, although they disagreed how that should be done. An opposing interpretation, represented by Pothier and Mocquereau, supported a free rhythm of equal note values, although some notes are lengthened for textual emphasis or musical effect. The modern Solesmes editions of Gregorian chant follow this interpretation. Mocquereau divided melodies into two- and three-note phrases, each beginning with an ictus, akin to a beat, notated in chantbooks as a small vertical mark. These basic melodic units combined into larger phrases through a complex system expressed by cheironomic hand-gestures.[49] This approach prevailed during the twentieth century, propagated by Justine Ward's program of music education for children, until Vatican II diminished the liturgical role of chant and new scholarship "essentially discredited" Mocquereau's rhythmic theories.[50]

Common modern practice favors performing Gregorian chant with no beat or regular metric accent, largely for aesthetic reasons.[51] The text determines the accent while the melodic contour determines the phrasing. The note lengthenings recommended by the Solesmes school remain influential, though not prescriptive.

Liturgical functions

Gregorian chant is sung in the Office during the canonical hours and in the liturgy of the Mass. Texts known as accentus are intoned by bishops, priests, and deacons, mostly on a single reciting tone with simple melodic formulae at certain places in each sentence. More complex chants are sung by trained soloists and choirs. The most complete collection of chants is the Liber usualis, which contains the chants for the Tridentine Mass and the most commonly used Office chants. Outside of monasteries, the more compact Graduale Romanum is commonly used.

Proper chants of the Mass

The Introit, Gradual, Alleluia, Tract, Sequence, Offertory and Communion chants are part of the Proper of the Mass. "Proper" is cognate with "property"; each feast day possesses its own specific texts and chants for these parts of the liturgy.

Introits cover the procession of the officiants. Introits are antiphonal chants, typically consisting of an antiphon, a psalm verse, a repeat of the antiphon, an intonation of the Doxology, and a final repeat of the antiphon. Reciting tones often dominate their melodic structures.

Graduals are responsorial chants that intone a lesson following the reading of the Epistle. Graduals usually result from centonization; stock musical phrases are assembled like a patchwork to create the full melody of the chant, creating families of musically related melodies.

The Alleluia is known for the jubilus, an extended joyful melisma. It is common for different Alleluia texts to share essentially the same melody. The process of applying an existing melody to a new Alleluia text is called adaptation. Alleluias are not sung during penitential times, such as Lent. Instead, a Tract is chanted, usually with texts from the Psalms. Tracts, like Graduals, are highly centonized.

Sequences are sung poems based on couplets. Although many sequences are not part of the liturgy and thus not part of the Gregorian repertory proper, Gregorian sequences include such well-known chants as Victimae paschali laudes and Veni Sancte Spiritus. According to Notker Balbulus, an early sequence writer, their origins lie in the addition of words to the long melismas of the jubilus of Alleluia chants.[52]

Offertories are sung during the giving of offerings. Offertories once had highly prolix melodies in their verses, but the use of verses in Gregorian Offertories disappeared around the twelfth century.

Communions are sung during the distribution of the (Catholic Church)Eucharist. Communion melodies are often tonally unstable, alternating between B-natural and B-flat. Such Communions often do not fit unambiguously into a single musical mode.

Ordinary chants of the Mass

The Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei use the same text in every service of the Mass. Because they follow the regular invariable "order" of the Mass, these chants are called "Ordinary of the Mass."

The Kyrie consists of a threefold repetition of "Kyrie eleison" ("Lord, have mercy"), a threefold repetition of "Christe eleison" ("Christ have mercy"), followed by another threefold repetition of "Kyrie eleison." In older chants, "Kyrie eleison imas" ("Lord, have mercy on us") can be found. The Kyrie is distinguished by its use of the Hellenistic Greek language instead of Latin. Because of the textual repetition, various musical repeat structures occur in these chants. The following, Kyrie ad. lib. VI as transmitted in a Cambrai manuscript, uses the form ABA CDC EFE', with shifts in tessitura between sections. The E' section, on the final "Kyrie eleison," itself has an aa'b structure, contributing to the sense of climax.[53]listen Kyrie 55, Vatican ad lib. VI, Cambrai.ogg ]Kyrie 55, Vatican ad lib. VI, from Cambrai, Bibl. Mun. 61, fo.155v, as transcribed by David Hiley, example of musical repeat structures in Gregorian chant.

The Gloria in excelsis Deo recites the Greater Doxology, and the Credo intones the Nicene Creed. Because of the length of these texts, these chants often break into musical subsections corresponding with textual breaks. Because the Credo was the last Ordinary chant to be added to the Mass, there are relatively few Credo melodies in the Gregorian corpus.

The Sanctus and the Agnus Dei, like the Kyrie, also contain repeated texts, which their musical structures often exploit.

Technically, the Ite missa est and the Benedicamus Domino, which conclude the Mass, belong to the Ordinary. They have their own Gregorian melodies, but because they are short and simple, and have rarely been the subject of later musical composition, they are often omitted in discussion.

Chants of the office

Gregorian chant is sung in the canonical hours of the monastic Office, primarily in antiphons used to sing the Psalms, in the Great Responsories of Matins, and the Short Responsories of the Lesser Hours and Compline. The psalm antiphons of the Office tend to be short and simple, especially compared to the complex Great Responsories. At the close of the Office, one of four Marian antiphons is sung. These songs, Alma Redemptoris Mater (see top of article), Ave Regina caelorum, Regina caeli laetare, and Salve, Regina, are relatively late chants, dating to the eleventh century, and considerably more complex than most Office antiphons. Willi Apel has described these four songs as "among the most beautiful creations of the late Middle Ages."[54]

Influence

Medieval and Renaissance music

Gregorian chant had a significant impact on the development of medieval music and Renaissance music. Modern staff notation developed directly from Gregorian neumes. The square notation that had been devised for plainchant was borrowed and adapted for other kinds of music. Certain groupings of neumes were used to indicate repeating rhythms called rhythmic modes. Rounded noteheads increasingly replaced the older squares and lozenges in the 15th and 16th centuries, although chantbooks conservatively maintained the square notation. By the 16th century, the fifth line added to the musical staff had become standard. The The F clef or bass clef and the flat, Natural sign, and sharp accidentals derived directly from Gregorian notation.[55]

Gregorian melodies provided musical material and served as models for tropes and liturgical dramas. Vernacular hymns such as "Christ ist erstanden" and "Nun bitten wir den heiligen Geist" adapted original Gregorian melodies to translated texts. Secular tunes such as the popular Renaissance "In Nomine" were based on Gregorian melodies. Beginning with the improvised harmonizations of Gregorian chant known as organum, Gregorian chants became a driving force in medieval and Renaissance polyphony. Often, a Gregorian chant (sometimes in modified form) would be used as a cantus firmus, so that the consecutive notes of the chant determined the harmonic progression. The Marian antiphons, especially Alma Redemptoris Mater, were frequently arranged by Renaissance composers. The use of chant as a cantus firmus was the predominant practice until the Baroque period, when the stronger harmonic progressions made possible by an independent bass line became standard.

The Catholic Church later allowed polyphonic arrangements to replace the Gregorian chant of the Ordinary of the Mass. This is why the Mass as a compositional form, as set by composers like Palestrina or Mozart, features a Kyrie but not an Introit. The Propers may also be replaced by choral settings on certain solemn occasions. Among the composers who most frequently wrote polyphonic settings of the Propers were William Byrd and Tomás Luis de Victoria. These polyphonic arrangements usually incorporate elements of the original chant.

Twwentieth century

The renewed interest in early music in the late 19th century left its mark on 20th-century music. Gregorian influences in classical music include the choral setting of four chants in "Quatre motets sur des thèmes Grégoriens" by Maurice Duruflé, the carols of Peter Maxwell Davies, and the choral work of Arvo Pärt. Gregorian chant has been incorporated into other genres, such as the Enigma's musical project "Sadeness (Part I)," the chant interpretation of pop and rock by the German band Gregorian, the techno project E Nomine, and the work of black metal band Deathspell Omega. Norwegian black metal bands utilize Gregorian-style chants for clean vocal approach, featuring singers such as Garm or ICS Vortex of Borknagar and Dimmu Borgir, and Ihsahn of the band Emperor. The modal melodies of chant provide unusual sounds to ears attuned to modern scales.

Gregorian chant as plainchant experienced a popular resurgence during the New Age music and world music movements of the 1980s and 1990s. The iconic album was Chant, recorded by the Benedictine Monks of the Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos, which was marketed as music to inspire timeless calm and serenity. It became conventional wisdom that listening to Gregorian chant increased the production of beta waves in the brain, reinforcing the popular reputation of Gregorian chant as tranquilizing music.[56]

Gregorian chant has often been parodied for its supposed monotony, both before and after the release of Chant. Famous references include the flagellant monks in Monty Python and the Holy Grail intoning "Pie Jesu Domine" and the karaoke machine of public domain music featuring "The Languid and Bittersweet 'Gregorian Chant No. 5'" in the Mystery Science Theatre 3000 episode Pod People.[57]

The asteroid 100019 Gregorianik is called Meanings of asteroid names or named in its honor, using the German short form of the term.

Notes

- ↑ Development of notation styles is discussed at Dolmetsch online, Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ↑ The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Second Vatican Council. The Catholic Encyclopedia addresses this point at length: plainchant article. This view is held at the highest levels, including Pope Benedict XVI: Catholic World News 28 June 2006 Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ↑ David Hiley. Western Plainchant- A Handbook. (Clarendon Press, 1995), 484-485.

- ↑ Willi Apel. Gregorian Chant. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1990), 34.

- ↑ Apel, 74.

- ↑ Hiley (1995), 484-487

- ↑ James McKinnon, ed. Antiquity and the Middle Ages (Prentice Hall, 1990), 72.

- ↑ James W. McKinnon. "Christian Church, music of the early." Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy Retrieved April 21, 2007. (subscription access)

- ↑ Hiley 1995, 486.

- ↑ McKinnon, 320.

- ↑ H. Bewerung, "Gregorian chant," The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. VI. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ↑ Apel, 79.

- ↑ McKinnon, 114.

- ↑ David Wilson. Music of the Middle Ages (Schirmer Books, 1990), 13.

- ↑ Wilson, 10.

- ↑ Hiley, 604.

- ↑ Apel, 80.

- ↑ Richard Hoppin. Medieval Music (W. W. Norton & Company, 1978), 47.

- ↑ Carl Parrish. A Treasury of Early Music. (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1986), 8-9

- ↑ Apel, 288-289.

- ↑ Hiley, 622.

- ↑ Hiley, 624-627.

- ↑ The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, Second Vatican Council Sacrosanctum Concilium, 4 December, 1963, www.christusrex.org. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- ↑ Hoppin, Medieval Music (1978), 85-88.

- ↑ Apel, Gregorian Chant p. 203

- ↑ Hoppin, Anthology of Medieval Music (W. W. Norton & Company, 1978), 11.

- ↑ Hoppin, Medieval Music (1978), 81.

- ↑ Hoppin, Medieval Music (1978, 123.

- ↑ Hoppin, Medieval Music (1978), 131.

- ↑ Wilson, 11.

- ↑ Hoppin, Medieval Music (1978), 64-65.

- ↑ Hoppin, Medieval Music (1978), 82.

- ↑ Wilson, 22.

- ↑ Apel, 166-178

- ↑ Hiley (1995), 608-610.

- ↑ Apel, 171-172.

- ↑ Apel, 256-257.

- ↑ Wilson, 21.

- ↑ Apel, 258-259.

- ↑ Apel, 344-363.

- ↑ Hiley (1995), 110-113.

- ↑ Kenneth Levy, "Plainchant," Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy Retrieved April 21, 2007. (subscription access)

- ↑ Carol Neuls-Bates, (ed.) Women in Music. (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1996), 3.

- ↑ Hiley (1995), 504.

- ↑ Apel, 312.

- ↑ Apel, 197.

- ↑ David Hiley, "Chant," Performance Practice: Music before 1600, Howard Mayer Brown and Stanley Sadie, eds., (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1990), 44. "The performance of chant in equal note lengths from the 13th century onwards is well supported by contemporary statements."

- ↑ Apel, 289.

- ↑ Apel, 127.

- ↑ Joseph Dyer. "Roman Catholic Church Music," Section VI.1, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy [1] (subscription access)]. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ↑ William P. Mahrt, "Chant," A Performer's Guide to Medieval Music, Ross Duffin, ed. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2000), 18.

- ↑ Richard Crocker. The Early Medieval Sequence. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 1-2.

- ↑ Hiley, (1995), 153.

- ↑ Apel, 404.

- ↑ Geoffrey Chew, and Richard Rastall. "Notation," Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy Retrieved April 21, 2007. (subscription access)

- ↑ Le Mee, Chant: The Origins, Form, Practice, and Healing Power of Gregorian Chant. 140.

- ↑ The Mystery Science Theater 3000 Amazing Colossal Episode Guide 39. ISBN 0553377833

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Graduale triplex. Tournai: Desclée& Socii, 1979. ISBN 285274094X

- Liber usualis Tournai: Desclée& Socii, 1953.

- Apel, Willi. Gregorian Chant. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1990. ISBN 0253206014

- Crocker, Richard. The Early Medieval Sequence. University of California Press, 1977. ISBN 0520028473

- Grout, Daniel J. A History of Western Music. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1960. ISBN 0393951421

- Hiley, David. "Chant." In Performance Practice: Music before 1600, 37-54. Edited by Howard Mayer Brown and Stanley Sadie. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1990. ISBN 0393028070

- Hiley, David. Western Plainchant: A Handbook. Clarendon Press, 1995. ISBN 0198165722

- Hoppin, Richard (ed.). Anthology of Medieval Music. W. W. Norton & Company, 1978. ISBN 0393090809

- Hoppin, Richard (ed.). Medieval Music. W. W. Norton & Company, 1978. ISBN 0393090906

- Le Mee, Catherine. Chant: The Origins, Form, Practice, and Healing Power of Gregorian Chant. Harmony, 1994. ISBN 0517700379

- Mahrt, William P. "Chant." In A Performer's Guide to Medieval Music. 1-22. Edited by Ross Duffin. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2000. ISBN 0253337526

- McKinnon, James (ed.). Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Prentice Hall, 1990. ISBN 0130361534

- Neuls-Bates, Carol (ed.). Women in Music. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1996. ISBN 1555532406

- Parrish, Carl. A Treasury of Early Music. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1992 (original 1986). ISBN 0486410889

- Robinson, Ray (ed.). Choral Music. W.W. Norton & Co., 1978. ISBN 0393090620

- Wagner, Peter. Einführung in die Gregorianischen Melodien. Ein Handbuch der Choralwissenschaft. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1911. (in German)

- Wilson, David. Music of the Middle Ages. Schirmer Books, 1990. ISBN 002872951X

External links

All links retrieved July 14, 2017.

- Sites of abbeys and schola according to the method of Dom Gajard

- Gregorian chant Catholic Encyclopedia

- William P. Mahrt, Gregorian Chant as a Paradigm of Sacred Music Sacred Music, Spring 2006.

- Lessons on Gregorian Chant: Notation, characteristics, rhythm, modes, the psalmody and scores Canticum Novum

- Justine Ward, The Reform of Church Music

- MIDI Collection of Traditional Catholic Hymns and chants

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.