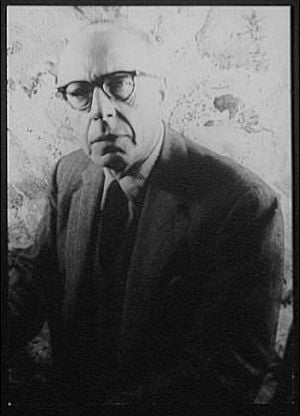

George Szell

György Széll, best known by his anglicized name, George Szell (June 7, 1897 – July 30, 1970), was a conductor and composer. He is remembered today for his long and successful tenure as music director of the Cleveland Orchestra from 1946 to 1970 and for the recordings of the standard classical repertory he made with Cleveland and other orchestras. It is said that Szell, among all conductors, had a baton with "one of the sharpest points," because his orchestras were distinguished by their precision.

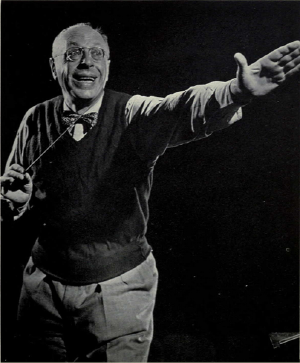

The primary aspect of the art of conducting can be said to be bringing a sense of "oneness" to the performance of a given musical work. George Szell was not only a supreme baton technician, but as a composer and pianist, he was known for his preparedness and having an encyclopedic understanding of the basic orchestral repertory. His fastidious attention to detail helped make the Cleveland Orchestra one of the greatest symphonic ensembles in the world. By bringing a sense of "oneness" and unity to his performances on a consistent basis, he realized a very high level of artistry in his craft.

Early career

Szell (pronounced "cell") was born in Budapest but grew up in Vienna. He began his formal music training as a pianist, studying with Richard Robert, a personal friend of Johannes Brahms. One of Robert's other students was Rudolf Serkin; Szell and Serkin became lifelong friends and music collaborators. In addition to studying piano, Szell was schooled in music composition by Eusebius Mandyczewski in Leipzig.

At age eleven, Szell began touring Europe as a pianist and composer, making his London debut at that age. Newspapers declared him "the next Mozart." When he was fourteen, he signed a ten-year exclusive publishing contract with Universal Edition in Vienna. Throughout his teenage years he performed with orchestras in this dual role, eventually making appearances as composer, pianist and conductor, as he did with the Berlin Philharmonic at age seventeen. Szell's work as a composer is virtually unknown today. In addition to writing original pieces, he arranged Bedřich Smetana's String Quartet No. 1, From My Life, for orchestra.

Conducting career

Szell quickly realized that he was never going to make a career out of being a composer or pianist, and that he much preferred the artistic control that was granted to conductors. He made an unplanned public debut as a conductor when he was sixteen. When the orchestra at a summer resort where he was vacationing with his family suddenly found itself without a conductor (due to his arm being injured), Szell was asked to substitute. Szell quickly turned to conducting full time. While he ceased composing, throughout the rest of his life he occasionally played the piano with chamber ensembles and as an accompanist. Despite his rare appearances as a pianist after his teens, he remained in good form. During his Cleveland years, he occasionally would demonstrate to guest pianists how he thought they should play a certain passage.

Influence of Strauss

In 1915, at the age of 18, Szell won an appointment with Berlin's Royal Court Opera (now known as the Staatsoper). There, he was befriended by its Music Director, Richard Strauss. Strauss instantly recognized Szell's talent and was particular impressed with how well he conducted his own music –- Strauss once said that he could die a happy man knowing that there was someone who performed his music so perfectly. In fact, Szell ended up conducting part of the world premiere recording of Don Juan for Strauss. Due to oversleeping, Strauss showed up an hour late to the recording session. Strauss had Szell rehearse the orchestra for him, and since the recording session was prepaid for, and there was no Strauss, but Szell was there, Szell conducted the first half of the recording (since no more than five minutes could be fit onto a side of a 78, the music was broken up into four chunks). Strauss arrived as Szell was finishing conducting the second part; he exclaimed that what he heard was so good that it could go out under his own name. Strauss went on to conduct the last two parts, leaving the Szell conducted half of the recording as part of the full world premiere recording of Don Juan.

Szell credited Strauss as being a major influencing force of his conducting style. Much of his baton technique, the Cleveland Orchestra’s transparent lean sound, and Szell's willingness to be an orchestra builder came from Strauss. The two remained friends after Szell left the Royal Court Opera in 1919. Even after World War II, when Szell had settled in the United States, Strauss kept track of how his protégé was doing.

Conducting operas

During the 1920s and 1930s Szell moved around from opera houses and orchestras in Europe: in Berlin, Strasbourg (where he succeeded Otto Klemperer at the Municipal Theatre), Prague, Darmstadt, Düsseldorf, and Glasgow, before becoming principal conductor, in 1924, of the Berlin Staatsoper (which by now had replaced the Royal Opera). In 1930, Szell made his United States debut with the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra. At this time he was better known as an opera conductor than orchestral.

Move to the U.S.

As a Jew living in Europe at the end of the 1930s, Szell saw the warning signs, and in August of 1939, moved to New York City. After spending a year teaching, Szell began to receive frequent guest conducting invitations. Important among these invitations was a series of four concerts with Arturo Toscanini’s NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1941. In 1942, he made his Metropolitan Opera debut; he conducted the company regularly for the next four years. In 1943, he made his New York Philharmonic debut. In 1946, he became a naturalized U.S. citizen.

The Cleveland Orchestra: 1946 to 1970

In 1946, Szell was asked to become the Music Director of the Cleveland Orchestra. At the time the Cleveland Orchestra was a well regarded regional American orchestra (the top-tier American orchestras were: Philadelphia Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, and NBC Symphony Orchestra). For Szell, working in Cleveland would represent an opportunity to create his own personal ideal orchestra, one which would combine the virtuosity of the best American ensembles, with the homogeneity of tone of the best European orchestras. Szell made it clear to the managers of the orchestra that if they wanted him to be their next conductor, they would have to agree to give him total artistic control; they agreed. He held this post until his death.

The next decade was spent firing musicians, carefully hiring replacements, increasing the orchestra's roster to over one hundred players, and relentlessly drilling the orchestra. Szell's rehearsals were legendary for their intensity. Absolute perfection was demanded from every player. Musicians would be dismissed on the spot for making too many mistakes or simply questioning Szell's authority. (Although Szell was not alone in this practice—Toscanini was nothing if not dictatorial—such firings would not happen today: musicians' unions are much stronger now than they were then.) If Szell heard a player practicing backstage before a concert and did not like what he heard, he would not hesitate to berate the musician and give detailed notes on how the music should be played, despite the concert being minutes away. Szell’s autocratic style extended to giving suggestions to the Severance Hall janitorial staff on mopping technique and what brand of toilet paper to use in the restrooms.

Szell proudly boasted that "the Cleveland Orchestra gives seven concerts a week and the public is invited to two." Some critics found the orchestra to sound over-rehearsed in concert, lacking spontaneity. Szell conceded this critique, saying that the orchestra did much of its best work during rehearsals. But Szell's high standards paid off. By the end of the 1950s, it became clear to the world that the Cleveland Orchestra, noted for its flawless precision and chamber-like sound, would take its place alongside the greatest orchestras in America and Europe.

In addition to taking the orchestra on annual tours to Carnegie Hall and the East Coast, Szell led the orchestra on its first international tours to Europe, and later to Japan and Korea.

Conducting style

While Szell was an autocratic taskmaster, he maintained legitimacy through meticulously preparing for rehearsals. A chief component of his rehearsal process was arranging the entire score for piano and playing it straight through, resulting in a mastery of the score. He would only take on conducting students if they too possessed this ability (one of them was James Levine). A literalist in his approach, Szell felt that everything he needed to know about how to conduct a score was in its pages; no knowledge of the composer’s biography was needed. He was more concerned about phrasing, transparency, balance and architecture than emotionalism in order to bring to fruition the composer's intentions as written in the score. As a result, Szell’s conducting was, and still is, sometimes criticized for being cold.

In response to such criticism, Szell expressed this credo: "The borderline is very thin between clarity and coolness, self-discipline and severity. There exist different nuances of warmth—from the chaste warmth of Mozart to the sensuous warmth of Tchaikovsky, from the noble passion of Fidelio to the lascivious passion of Salome. I cannot pour chocolate sauce over asparagus."

Repertoire

Szell mainly stuck to conducting the core Austro-German classical and romantic repertoire, often saying that there was little music of any value being newly composed. Despite his disdain for contemporary music, he was a champion of numerous composers of his era, such as Walton, Prokofiev, Hindemith, and Bartók. Ironically, while Szell’s Mahler recordings are among his most famous, he never claimed to be a champion of the composer, as so many of his peers did in the 1950s and 1960s. In an interview late in his career in Cleveland, he remarked that, "I am a very late convert to Mahler." Szell explained that when he was growing up, Mahler was better known as a conductor than composer, and that was how he always thought of him. At the same time, Szell championed the music of Haydn and Mozart in a period when those composers were little represented in concert programs; his recordings of the first six of Haydn’s London symphonies remain models, nearly forty years after they were made, of how to get a modern orchestra to approach an increasingly foreign style.

Other orchestras

After World War II, Szell became closely associated with the Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam, where he was a frequent guest conductor and made a number of recordings. He also regularly appeared with the London Symphony Orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic (he often complained that Vienna would make it a point to have him conduct the ensemble's least experienced players, in the hope that he could teach them something) and at the Salzburg Festival. In the last years of his life, he also served as Musical Adviser to the New York Philharmonic.

Personal life

Szell's somewhat bullying personality carried over into his personal relationships also. He was notorious for destroying the reputations of other musicians, and was always a very prickly person who could and would summarily cut off all contact with a friend or colleague over some perceived slight or slip in standards. When not making music, he was a gourmet cook and an automobile enthusiast. He regularly refused the services of the orchestra's chauffeur and drove his own Cadillac to rehearsals in Cleveland until almost the end of his life.

Legacy

While many conductors can legitimately be called "legendary" and "among the greatest of the twentieth century," few can also lay claim to having turned a provincial orchestra into one of the greatest orchestras in the world. This Szell did. Through his recordings and the present day Cleveland Orchestra, Szell remains a presence in the classical music world, more than thirty-five years after his death. Christoph von Dohnányi summarized this best when he lamented at the end of his tenure as Music Director of the orchestra (1984 to 2002) that the problem with being the conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, was that when the orchestra gave a good performance, it was Szell who got the good review.

Recordings

A selection of Szell's most famous recordings (all with the Cleveland Orchestra unless otherwise noted):

- Ludwig van Beethoven: The 9 Symphonies (1957-64, Sony)

- Ludwig van Beethoven: The Piano Concertos; Leon Fleisher(p) (1959-61, Sony)

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Missa Solemnis (1967, TCO)

- Johannes Brahms: Piano Concertos; Leon Fleisher(p) (1958 & 1962, Sony)

- Johannes Brahms: Piano Concertos; Rudolf Serkin(p) (1968 & 1966, Sony)

- Johannes Brahms: Violin Concerto; David Oistrakh(vn) (1969, EMI)

- Johannes Brahms: Concerto for violin and violoncello; David Oistrakh(vn), Mstislav Rostropovich(vc) (1969, EMI)

- Antonín Dvořák: Symphonies Nos.7-9 (1958-60, Sony)

- Antonín Dvořák: Slavonic Dances (1962-65, Sony)

- Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto; Pablo Casals(vc)/Czech Philharmonic Orchestra (1937, HMV)

- Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto; Pierre Fournier(vc) / Berliner Philharmoniker (1962, DG)

- Joseph Haydn: Symphonies Nos. 92-99 (1957-69, Sony)

- Zoltán Kodály: Háry János Suite (1969, Sony)

- Gustav Mahler: Symphony No.4; Judith Raskin(S) (1965, Sony)

- Gustav Mahler: Symphony No.6 (1967, Sony)

- Gustav Mahler: Des Knaben Wunderhorn; Elisabeth Schwarzkopf(S), Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau(Br)/London Symphony Orchestra (1968, EMI)

- Felix Mendelssohn: Symphony No.4 (1962, Sony)

- Felix Mendelssohn: Incidental Music from A Midsummer Night's Dream, op.21 & 61 (1967, Sony)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Symphonies Nos.35, 39-41 (1960-63)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Serenade No.13 in G major, K.525 'Eine kleine Nachtmusik'(1968, Sony)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Concertos; Robert Casadesus(p) (1955-68, Sony)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Quartets Nos.1-2; Budapest String Quartet,Szell(p) (1946, Sony)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Violin Sonatas, K.301 & 296; Raphael Druian(vn), Szell(p) (1967, Sony)

- Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition (1963, Sony)

- Sergei Prokofiev: Symphony No.5 (1959, Sony)

- Sergei Prokofiev: Piano Concertos Nos.1 & 3; Gary Graffman(p) (1966, Sony)

- Franz Schubert: Symphony No.9 "The Great" (1957, Sony)

- Robert Schumann: The Symphonies (1958-60, Sony)

- Jean Sibelius: Symphony No.2; Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (1964, Philips)

- Jean Sibelius: Symphony No.2 (1970, Sony) - This was Szell's last recording

- Richard Strauss: Don Juan (1957, Sony)

- Richard Strauss: Don Quixote; Pierre Fournier(vc), Abraham Skernick(va) (1960, Sony)

- Richard Strauss: Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche (1957, Sony)

- Richard Strauss: Tod und Verklärung (1957, Sony)

- Richard Strauss: 4 Last Songs; Elisabeth Schwarzkopf(S) / Radio-Symfonie-Orchester Berlin (1965, EMI)

- Igor Stravinsky: The Firebird Suite (1919 version) (1961, Sony)

- Pyotr Tchaikovsky: Symphony No.4; London Symphony Orchestra (1962, Decca)

- Pyotr Tchaikovsky: Symphony No.5 (1959, Sony)

- Richard Wagner: Overtures, Preludes & Extracts from the Ring (1962-68, Sony)

- William Walton: Symphony No.2 (1961, Sony)

- William Walton: Partita for Orchestra (1959, Sony)

- William Walton: Variations on Theme by Hindemith (1964, Sony)

Most of Szell's recordings were made with the Cleveland Orchestra for Epic/Columbia/CBS (now Sony). Few of his mono recordings have been reissued. Many live stereo recordings of repertoire Szell never conducted in the studio exist, both with the Cleveland Orchestra and other orchestras.

It is also worth noting that the recording of Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 4 with the London Symphony listed above was never released during his lifetime, as it did not meet his standards, yet it has won wide acclaim since Decca issued it in the 1970s. Producer John Culshaw told the story of Szell's annoyance at seeing a number of different players at the recording session from those with whom he had rehearsed and performed in concert; Culshaw then intentionally kept the playback levels low in the control room, heightening the impression of dullness and making the conductor even more angry. When Szell returned to the podium he unleashed such vehemence in his conducting that the results still sound electrifying nearly a half-century afterwards.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Angell, Lawrence, and Bernette Jaffe. Tales from the Locker Room: An Anecdotal Portrait of George Szell and his Cleveland Orchestra. ATBOSH Media, Limited, 2015. ISBN 978-1626130531

- Burrows, Raymond, Bessie Carroll Redmond, George Szell, and George Clark Leslie. Symphony Themes. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1942. OCLC 405046

- Kraus, Marcia Hansen. George Szell's Reign: Behind the Scenes with the Cleveland Orchestra. University of Illinois Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0252041310

- Rudolf, Max. The Grammar of Conducting: A Practicel Study of Modern Baton Technique. New York: G. Schirmer, 1969. ASIN B000AV48C0

External links

All links retrieved October 18, 2022.

- George Szell Cleveland Arts Prize

- George Szell - Beethoven Symphony No. 5 YouTube

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.