Dziga Vertov

Dziga Vertov (Russian: Дзига Вертов), (January 2, 1896 – February 12, 1954) was a Russian pioneer documentary film and newsreel director. His brothers, Boris Kaufman and Mikhail Kaufman were also notable filmmakers. Along with Sergei Eisenstein, Vertov helped to create a distinctive cinema that arose in the context of the changing era of the Bolshevik revolution. Like Eisenstein, Vertov embraced this revolutionary spirit in his films. His Man with Movie Camera was one of the truly pioneering works of the early cinema, creating many of the camera techniques that have become standard in the film industry, including double exposure, freeze frames, jump cuts, split screens, extreme closeups, and tracking shots, among others. Like many artists of this period, he was forced by the rise and official sanction of socialist realism, in 1934, to cut his personal artistic output significantly, eventually becoming little more than an editor for Soviet newsreels.

Early years

Born Denis Abramovich Kaufman (Russian: Денис Абрамович Кауфман) into a family of Jewish intellectuals in Białystok, Congress Poland, then a part of the Russian Empire, he Russified his Jewish patronymic (middle name taken from the father's name) to Arkadievich in his youth. Kaufman studied music at Białystok Conservatory until his family fled from the invading German army to Moscow in 1915. The Kaufmans soon settled in St. Petersburg, where Denis Kaufman began writing poetry, science fiction, and satire. In 1916-1917, Kaufman was studying medicine at the Psychoneurological Institute in St. Petersburg and experimenting with "sound collages" in his free time. Kaufman adopted the name "Dziga Vertov," which means "spinning top;" Vertov's political writings and his work on the Kino-Pravda (Cinema Verite) newsreel series show a revolutionary romanticism.

Career after the October Revolution

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, at the age of 22, Vertov began editing for Kino-Nedelya (Кино-Неделя, literally the Cinema Weekly, the Moscow Cinema Committee's weekly film series, and the first newsreel series in Russia). While working for Kino-Nedelya he met Elizaveta Svilova, who at the time was employed in film preservation; she was later to become his wife. The first issue of the series came out in June 1918.

Vertov worked on the series for three years, helping establish and run a film-car on President Kalinin's agit-train during the ongoing Russian Civil War between the Communists and the counterrevolutionaries. Some of the cars on the agit-trains were equipped with actors for live performances or printing presses; Vertov's had equipment to shoot, develop, edit, and project film. The trains went to battlefronts on agitprop (agitation-propaganda) missions intended primarily to bolster the morale of the troops; they were also intended to stir up revolutionary fervor of the masses.

In 1919, Vertov compiled newsreel footage for his documentary, Anniversary of the Revolution; in 1921, he compiled History of the Russian Civil War. The so-called "Council of Three," a group issuing manifestos in LEF, a radical Russian newsmagazine, was established in 1922; the group's "three" were Vertov, his wife, and editor Elizaveta Svilova, and his brother and cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman. Vertov's interest in machinery led to a curiosity about the mechanical basis of film. Vertov's brother, Boris Kaufman, was a noted cinematographer who worked for directors such as Elia Kazan and Sidney Lumet; his other brother, Mikhail Kaufman, worked as Vertov's cinematographer until he became a documentarian in his own right.

Kino-Pravda

In 1922, the year that Nanook of the North was released, Vertov started the Kino-Pravda series. The series took its title from the official government newspaper, Pravda. "Kino-Pravda" continued Vertov's agit-prop bent.

Vertov's driving vision, expounded in his frequent essays, was to capture "film truth"—that is, fragments of actuality which, when organized together, have a deeper truth that cannot be seen with the naked eye. In the "Kino-Pravda" series, Vertov focused on everyday experiences, eschewing "bourgeois" concerns, filming marketplaces, bars, and schools instead, sometimes with a hidden camera, without asking permission. The cinematography is simple, functional, unelaborate—perhaps a result of Vertov's disinterest in both "beauty" and "art." Twenty-three issues of the series were produced over a period of three years; each issue lasted about twenty minutes and usually covered three topics. The stories were typically descriptive, not narrative, including vignettes and exposés, showing, for instance, the renovation of a trolley system, the organization of farmers into communes, and the trial of Social Revolutionaries; one story shows starvation in the nascent Marxist state. The episodes of "Kino-Pravda" usually did not include reenactments or stagings (one exception is the segment about the trial of the Social Revolutionaries: The scenes of the selling of the newspapers on the streets and the people reading the papers in the trolley were both staged for the camera). Propagandistic tendencies are also present, but are done with subtlety. In the episode featuring the construction of an airport, one shot shows the former Tsar's tanks helping prepare a foundation, with an inter-title reading "Tanks on the labor front."

Vertov clearly intended an active relationship with his audience in the series—in the final segment he includes contact information—but by the 14th episode the series had become so experimental that some critics dismissed Vertov's efforts as "insane." Vertov responded to their criticisms with the assertion that the critics were hacks nipping "revolutionary effort" in the bud, concluding the essay with his promise to "explode art's Tower of Babel, or the subservience of cinematic technique to narrative, commonly known as the Institutional Mode of Representation.

By this point in his career, Vertov was clearly and emphatically dissatisfied with the narrative tradition, expressing his hostility towards dramatic fiction of any kind both openly and repeatedly; he regarded drama as another "opiate of the masses."

The "Kino-Pravda" series, while influential, had a limited release. By the end of the series, Vertov made liberal use of stop motion, freeze frames, and other cinematic "artificialities," giving rise to criticisms not just of his trenchant dogmatism, but also of his cinematic technique. Vertov explains himself in "On 'Kinopravda:'" Tn editing "chance film clippings" together for the Kino-Nedelia series, he "began to doubt the necessity of a literary connection between individual visual elements spliced together…. This work served as the point of departure for 'Kinopravda.'" Towards the end of the same essay, Vertov mentions an upcoming project which seems likely to be Man with the Movie Camera, calling it an "experimental film" made without a scenario; just three paragraphs above, Vertov mentions a scene from "Kino Pravda" which should be quite familiar to viewers of Man with the Movie Camera: "The peasant works, and so does the urban woman, and so too, the woman film editor selecting the negative…."

With Lenin's admission of limited private enterprise through his New Economic Policy, Russia began receiving dramatic films from afar, an occurrence that Vertov regarded with undeniable suspicion, calling drama a "corrupting influence" on the proletarian sensibility ("On 'Kinopravda,'" 1924). By this time, Vertov had been using his newsreel series as a pedestal to vilify dramatic fiction for several years; he continued his criticisms even after the warm reception of Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin in 1925. Potemkin was a fictionalized recounting of the story of a mutiny on a battleship which came about as a result of the sailors' mistreatment; the film was an obvious but skillful propaganda piece glorifying the proletariat. Vertov lost his job at Sovkino (Soviet films) in January 1927, possibly as a result of criticizing a film which effectively parroted the Communist party line.

Man with a Movie Camera

Man with a Movie Camera, sometimes The Man with the Movie Camera, The Man with a Camera, The Man With the Kinocamera, or Living Russia (Russian: Человек с киноаппаратом, Chelovek s kino-apparatom), is Vertov's experimental 1929 silent documentary film.

Vertov's feature film presents urban life in the Soviet Union, from dawn to dusk. Soviet citizens are shown at work and at play, interacting with the machinery of modern life. Vertov dispenses with characters, choosing to present images of modern Russia.

This film is famous for the range of cinematic techniques Vertov invents, deploys or develops, such as double exposure, fast motion, slow motion, freeze frames, jump cuts, split screens, Dutch angles, extreme closeups, tracking shots, footage played backwards, and a self-reflexive storyline (at one point it features a split screen tracking shot; the sides have opposite Dutch angles).

Overview

By the later segments of "Kino-Pravda," Vertov was experimenting heavily, looking to abandon what he considered film clichés (and receiving criticism for it); his experimentation was even more pronounced and dramatic by the time of Man with the Movie Camera. The film is intended to demonstrate Vertov's ideas about "life as it is" and "life caught unawares."

Some have criticized the obvious stagings in Man With the Movie Camera as being at odds with Vertov's credos. The scene of the woman getting out of bed and getting dressed is obviously staged, as is the reversed shot of the chess pieces being pushed off a chess board and the tracking shot which films Mikhail Kaufman riding in a car filming a third car.

Vertov's message about the prevalence and unobtrusiveness of filming was not yet true—cameras might have been able to go anywhere, but not without being noticed; they were too large to be hidden easily, and too noisy to remain hidden anyway. To get footage using a hidden camera, Vertov and his brother Mikhail Kaufman had to distract the subject with something else even louder than the camera filming them.

Vertov's intentions

Vertov says in his essay on "The Man with a Movie Camera" that he was fighting "for a decisive cleaning up of film-language, for its complete separation from the language of theater and literature." By the later segments of "Kino-Pravda," Vertov was experimenting heavily, looking to abandon what he considered film clichés (and receiving criticism for it); his experimentation was even more pronounced and dramatic by the time of Man with the Movie Camera. Some have criticized the obvious stagings in Man With the Movie Camera as being at odds with Vertov's credos "life as it is" and "life caught unawares:" The scene of the woman getting out of bed and getting dressed is obviously staged, as is the reversed shot of the chess pieces being pushed off a chess board and the tracking shot which films Mikhail Kaufman riding in a car filming a third car.

However, Vertov's two credos, often used interchangeably, are in fact distinct, as Yuri Tsivian points out in the audio commentary on the DVD for Man with the Movie Camera: for Vertov, "life as it is" means to record life as it would be without the camera present. "Life caught unawares" means to record life when surprised, and perhaps provoked, by the presence of a camera (16:04 on the commentary track). This explanation contradicts the common assumption that for Vertov "life caught unawares" meant "life caught unaware of the camera." All of these shots might conform to Vertov's credo "caught unawares."

Vertov belonged to a movement of filmmakers known as the kinocs, or kinokis. Vertov, along with other kino artists declared it their mission to abolish all non-documentary styles of film-making. This radical approach to movie making led to a slight dismantling of film industry: The very field in which they were working. The kinoc movement was despised by many filmmakers of the time. Vertov's crowning achievement, Man with a Movie Camera was his response to the critics who rejected his previous film, One-Sixth Part of the World. Critics declared that Vertov's overuse of "intertitles" was inconsistent with the code of filmmaking to which the 'kinos' subscribed.

Working within that context, Vertov dealt with much fear in anticipation of the film's release. He requested a warning to be printed in Soviet central Communist newspaper, Pravda, which spoke directly of the film's experimental, controversial nature. Vertov was worried that the film would be either destroyed or ignored by the public eye. Upon the official release of Man with a Movie Camera, Vertov issued a statement at the beginning of the film, which read:

|

|

- This new experimentation work by Kino-Eye is directed towards the creation of an authentically international absolute language of cinema—ABSOLUTE KINOGRAPHY—on the basis of its complete separation from the language of theatre and literature."

Stylistic aspects

Because of the doubts before screening, and the great anticipation, which came from Vertov's pre-screening statements, the film had gained a colossal interest before it was even shown. Working within a Marxist state, Vertov strove to create a futuristic city that would serve as a commentary on existing ideals in the Soviet ideology. The kino’s aesthetic is achieved through the portrayal of electrification, industrialization, and the achievements of workers through hard labor. The film represents a precursor to modernism in film.

On a more technical note, Man with a Movie Camera's use of double exposure and seemingly "hidden" cameras disrupted the standard linear motion picture, creating a surreal montage. In many scenes, characters change size or appear underneath other objects through double exposure. Because of these technical innovations, the film's pace is fast moving and enthralling. The sequences and close-ups capture emotions without the need for dialogue. The film's lack of "actors" and "sets" makes for a unique view of the everyday world; one "directed toward the creation of a genuine, international, purely cinematic language, entirely distinct from the language of theatre and literature."

Vertov's use of stylistic symbolism was especially effective in creating a universal theme throughout the film. For example, one scene splices hidden camera shots of a couple getting marriage certificates and another couple at a divorce registry office. Soon after, two old women are shown attending a funeral procession and a woman is shown giving birth to a child. These sharply cut shots create a jarring effect for the viewer.

Late career

Vertov's cinema success continued into the 1930s. In 1931, he released Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass, an examination into Soviet miners. Enthusiasm has been called a 'sound film', with sound recorded on location, and these mechanical sounds woven together, producing a symphony-like effect.

Three years later, Three Songs about Lenin looked at the revolutionary through the eyes of the Russian peasantry. For his film, however, Vertov had been hired by Mezhrabpomfilm(Gorky Film Studio), a Soviet studio that produced mainly propaganda efforts. To conform to the studio's, and the Soviet government's expectations, the film was edited to include Stalin and provide a more acceptable, "Stalinesque," ending. With the rise and official sanction of socialist realism in 1934, Vertov was forced to cut his personal artistic output significantly, eventually becoming little more than an editor for Soviet newsreels. Lullaby, perhaps the last film in which Vertov was able to maintain his artistic vision, was released in 1937. Dziga Vertov died of cancer in 1954, after surviving Stalin's purges.

Influence

Vertov's legacy still lives on today. His independent, explorative style influenced and inspired many filmmakers and directors. Film companies like "Vertov Industries" have emerged, attributing Dziga Vertov as a source of inspiration.

Quotes

- "It is far from simple to show the truth, yet the truth is simple."

Filmography

- 1919 Кинонеделя (Kino Nedelya, Cinema Week)

- 1919 Годовщина революции (Anniversary of the Revolution)

- 1922 История гражданской войны (History of the Civil War)

- 1924 Советские игрушки (Soviet Toys)

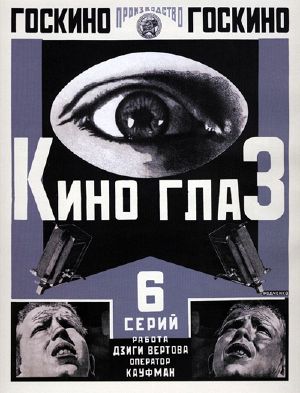

- 1924 Кино-глаз (Kino Glaz, Cinema Eye)

- 1925 Киноправда (Kino Pravda)

- 1926 Шестая часть мира (A Sixth of the World/The Sixth Part of the World)

- 1928 Одиннадцатый (The Eleventh)

- 1929 Человек с киноаппаратом (Man with the Movie Camera)

- 1931 Энтузиазм (Enthusiasm)

- 1934 Три песни о Ленине (Three Songs about Lenin)

- 1937 Памяти Серго Орджоникидзе (Memories of Sergo Ordzhonikidze)

- 1937 Колыбельная (Lullaby)

- 1938 Три героини (Three Heroines)

- 1942 Казахстан—фронту! (Kazakhstan for the Front!)

- 1944 В горах Ала-Тау (In the Mountains of Ala-Tau)

- 1954 Новости дня (News of the Day)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barnouw Erik. DocumentarCinema's Second Avant-Gardey: A History of the Non-fiction Film. Oxford University Press, 1974.

- Ellis, Jack C. The Documentary Idea: A Critical History of English-Language Documentary Film and Video. Prentice Hall, 1989. ISBN 0132171422

- Feldman, Seth. Peace between Man and Machine: Dziga Vertov's The Man with a Movie Camera.

- Grant, Barry Keith and Jeanette Sloniowski, eds. Documenting the Documentary: Close Readings of Documentary Film and Video. ISBN 0814326390

- Keathley, Christian M. Cinema's Second Avant-Garde. Master's Thesis, UF, 1993.

- Le Grice, Malcolm. Abstract Film and Beyond. Studio Vista, 1977. ISBN 0262620383

- Tode, Thomas, Barbara Wurm, eds. Dziga Vertov. The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum. Austrian Film Museum, 2006.

- Tsivian, Yuri. Dziga Vertov's Man with the Movie Camera. Audio Commentary Track. DVD.

- Vertov, Dziga. Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov. University of California Press, 1995. ISBN 0520056302

- Warren, Charles, ed. Beyond Document: Essays on Nonfiction Film. Wesleyan University Press, 1996. ISBN 0819562904

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.