Crow

| Crows | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Common Raven (Corvus corax)

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

See text. |

Crow is the common name for various large passerine birds in the genus Corvus of the family Corvidae, typically distinguished from ravens by smaller size and without the raven's shaggy throat feathers. The term crow also can be considered a more general term for all members of the Corvus genus, including ravens, rooks (one extant species), and jackdaws (two species). Since distinctions between birds commonly called crows and the other birds in Corvus have little or no taxonomic meaning, much of this article will be on the more general discussion of the genus.

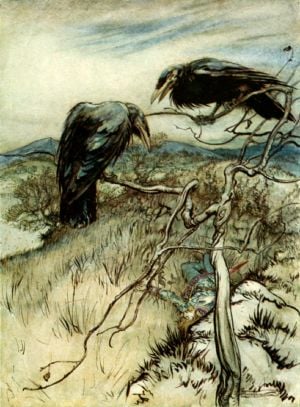

Crows, and especially ravens, often have poor reputations, being featured in legends and mythology as portents or harbingers of doom or death, because of their dark plumage, unnerving calls, and tendency to eat carrion. They are commonly thought to circle above scenes of death such as battles. However, in reality, crows are an integral part of ecosystems, consuming not just food that they scavenger, but also waste grain, invertebrates like earthworms, and small vertebrates as well. With their intelligence and unique behaviors, they add to the wonder of nature for humans.

Description

Like other members of the Corvidae family (jays, magpies, treepies and nutcrackers), members of the Corvus genus are characterized by strong feet and bills, feathered, rounded nostrils, strong tails and wings, rictal bristles, and a single molt each year (most passerines molt twice). The genus Corvus, including the crows, ravens, rooks (C. frugilegus), and jackdaws (C. dauricus and C. monedula), makes up over a third of the entire family.

Ranging in size from the relatively small pigeon-sized jackdaws (Eurasian and Daurian) to the common raven of the Holarctic region, and thick-billed raven of the highlands of Ethiopia, the 40 or so members of this genus occur on all temperate continents (except South America) and several offshore and oceanic islands (including Hawaii). The larger species of Corvus are the largest members of the passerine order. Raven is the common name given to the largest species of passerine birds in the genus Corvus.

In literary and fanciful usage, the collective noun for a group of crows is a "murder." Groups of ravens have historically been called an "unkindness." However, in practice, most people use the more generic term flock, and sometimes more macabre terms such as "swarm" or "horde."

Crows exhibit an array of complex behavioral characteristics. They make a wide variety of calls or vocalizations and have been observed responding to calls of other species as well. While the crows system is complex, it is debated whether it constitutes a language. Additionally, crows show remarkable examples of intelligence, engaging in mid air jousting to establish a pecking order, and manufacturing and using tools in search for food.

Crows versus ravens

There are two major groups of birds in Corvus: crows and ravens. (There are also two extant species commonly called jackdaws and one species commonly called rooks.)

Crows and ravens are generally treated as different birds. However, the grouping of birds as either crows or ravens has little or not real taxonomic meaning; for example, the Australian "ravens" are considered to be more closely related to the Australian "crows" than they are to the common raven (Corvus corax) (McGowan 2002).

McGowan (2002) lists several way in which ravens and crows are commonly differentiated, as far as these popular names are applied. For one, ravens are the larger birds, and usually have shaggy throat feathers and a larger bill, while the smaller species are labeled as crows. Ravens also tend to soar more than crows; crows never execute a somersault in flight that common ravens do; ravens are typically longer necked in flight than crows, and raven wings typically are shaped differently with longer primaries and more slotting between them.

Common ravens are distinguished from American crows by having wedge-shaped tails, while American crows, if they do show an apparent wedge shape to the tail, almost never show it when it is fanned as the birds soars or banks (McGowan 2002).

Behavior

Calls

Crows, in the more specific meaning of the word, make a wide variety of calls or vocalizations. Whether the crows' system of communication constitutes a language is a topic of debate and study. Crows have also been observed to respond to calls of other species; this behavior is presumably learned because it varies regionally.

Crows' vocalizations are complex and poorly understood. Some of the many vocalizations that crows make are a "caw," usually echoed back and forth between birds; a series of "caws" in discrete units, counting out numbers; a long caw followed by a series of short caws (usually made when a bird takes off from a perch); an echo-like "eh-aw" sound; and more. These vocalizations vary by species, and within each species vary regionally. In many species, the pattern and number of the numerical vocalizations have been observed to change in response to events in the surroundings (i.e. arrival or departure of crows). Crows can hear sound frequencies lower than those that humans can hear, which complicates the study of their vocalizations.

Intelligence

Crows and ravens show remarkable examples of intelligence, and Aesop's fable of The Crow and the Pitcher shows that humans have long viewed the crow as an intelligent animal.

Crows and ravens often score very highly on intelligence tests. Certain species top the avian IQ scale (Rincon 2005). Crows in the northwestern U.S. (a blend of Corvus brachyrhynchos and Corvus caurinus) show modest linguistic capabilities and the ability to relay information over great distances, live in complex, hierarchic societies involving hundreds of individuals with various "occupations," and have an intense rivalry with the area's less socially advanced ravens. Wild hooded crows in Israel have learned to use bread crumbs for bait-fishing (Hasson 2007). Crows will engage in a kind of mid-air jousting, or air-"chicken" to establish pecking order.

One species, the New Caledonian Crow, has recently been intensively studied because of its ability to manufacture and use its own tools in the day-to-day search for food, including dropping seeds into a heavy trafficked street and waiting for a car to crush it open (AP and BP 2003). Researchers from the University of Oxford, England and the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Germany showed that New Caledonian crows are able to invent tools by combining two or more elements, such as creating a long stick by combining shorter pieces in order to reach food (von Bayern et al 2018).

Color and society

Extra-specific uses of color in crow societies

Many crow species are all black. Most of their natural enemies, the raptors or "falconiformes," soar high above the trees, and hunt primarily on bright, sunny days when contrast between light and shadow is greatest. Crows take advantage of this by maneuvering themselves through the dappled shades of the trees, where their black color renders them effectively invisible to their enemies above, in order to set up complex ambush attacks. Fledglings are much duller than adults in appearances of great strategic importance to their societies.

It is perhaps here where we find perhaps the greatest difference between ravens and crows; ravens tend to soar high in the air as raptors do, and like raptors, are usually the target of ambushes by crows. Crows do not appear to perceive ravens as their own kind, but instead treat them as raptors.

While hawks tend to be the primary daytime predators of crows, their most deadly predators, in many areas, are the owls that hunt by night, preying upon crows sleeping helplessly in their roosts. Crows also will often mob owls much more fiercely when they find them in daylight than the hawks and other raptors. Frequently crows appear to "play" with hawks, taking turns "counting coup" while escorting the raptor out of their territory. Their attacks on owls, on the other hand, possess a definite serious quality.

Intra-specific uses of color in crow societies

Even in crow species characterized by being all black, one will still occasionally find variations, most of which appear to result from varying degrees of albinism, such as:

- an otherwise all-black crow stunningly contrasted by a full set of brilliant, pure-white primary feathers.

- complete covering in varying shades of gray (generally tending toward the darker side).

- blue or red, rather than swarthy eyes (blue being more common than red).

- Some combination of the above

The treatment of these rare individuals may vary from group to group, even within the same species. For example, one such individual may receive special treatment, attention, or care from the others in its group, while another group of the same species might exile such individuals, forcing them to fend for themselves. The reason for such behaviors, and why these behaviors vary as they do, has yet to be studied.

Evolution

Corvids appear to have evolved in central Asia and radiated out into North America, Africa, Europe, and Australia.

The latest evidence appears to point towards an Australasian origin for the early family (Corvidae) through the branch that would produce the modern groups such as jays, magpies, and large predominantly black Corvus (Barker et al. 2004). Crows had left Australasia and were now developing in Asia. Corvus has since re-entered Australia (relatively recently) and produced five species with one recognized sub-species.

The fossil record of crows is rather dense in Europe, but the relationships among most prehistoric species is not clear. Jackdaw-, crow- and raven-sized forms seem to have existed since long ago and crows were regularly hunted by humans up to the Iron Age, documenting the evolution of the modern taxa. American crows are not as well-documented.

A surprisingly high number of species have become extinct after human colonization; the loss of one prehistoric Caribbean crow could also have been related to the last ice age's climate changes.

Corvids and man

Certain species of Corvus have been considered pests: the common raven, Australian raven, and carrion crow have all been known to kill weak lambs as well as eating freshly dead corpses probably killed by other means. Rooks have been blamed for eating grain in the United Kindgom and Brown-necked Ravens for raiding date crops in desert countries (Goodwin and Gillmor 1977).

Hunting

In the United States, it is legal to hunt crows in most states, usually from around August to the end of March and anytime if they are causing a nuisance or health hazard. There is no bag limit when taken during the "crow hunting season." According to the United States Code of Federal Regulations, crows may be taken (i.e., shot) without a permit in certain circumstances. USFWS 50 CFR 21.43 (Depredation order for blackbirds, cowbirds, grackles, crows, and magpies) states that a Federal permit is not required to control these birds "when found committing or about to commit depredations upon ornamental or shade trees, agricultural crops, livestock, or wildlife, or when concentrated in such numbers and manner as to constitute a health hazard or other nuisance," provided

- that none of the birds killed or their parts are sold or offered for sale;

- that anyone exercising the privileges granted by this section shall permit any Federal or State game agent free and unrestricted access over the premises where the operations have been or are conducted and will provide them with whatever information required by the officer; and

- that nothing in the section authorizes the killing of such birds contrary to any State laws and that the person needs to possess whatever permit as may be required by the State.

In the United Kingdom it is illegal to kill or take a crow from the wild, and in Australia it is illegal to kill native birds.

Crows in heraldry

Crows and other corvidae in heraldry (family coats of arms) may represent harshness or avarice. The crow is depicted in heraldry with hairy feathers and is close by default. A crow speaking will have its mouth agape or open as if it were speaking. Other corvidae appearing in heraldry are the raven and the Cornish chough.

- The raven and crow are indistinguishable in use and appearance.

- The Cornish chough is only distinguishable if proper, meaning depicted as black with red beak and feet.

The crow may also be called a corbie, as in the canting arms of Corbet, c.1312. For canting purposes, the Cornish chough is sometimes called a beckit (Wilcox 2020).

Tradition, mythology and folklore

Crows, and especially ravens, often feature in European legends or mythology as portents or harbingers of doom or death, because of their dark plumage, unnerving calls, and tendency to eat carrion. They are commonly thought to circle above scenes of death such as battles. The Child ballad, The Three Ravens, depicts three ravens discussing whether they can eat a dead knight, but finds that his hawk, his hound, and his true love prevent them; in the parody version The Twa Corbies, these guards have already forgotten the dead man, and the ravens can eat their fill. Their depiction of evil has also led to some exaggeration of their appetite. In some films, crows are shown tearing out people's eyes while they are still alive.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Chaldean myth, the character Utnapishtim releases a dove and a raven to find land; however, the dove merely circles and returns. Only then does Utnapishtim send forth the raven, who does not return. Utnapishtim extrapolates from this that the raven has found land, which is why it has not returned. This would seem to indicate some acknowledgment of crow intelligence, which may have been apparent even in ancient times, and to some might imply that the higher intelligence of crows, when compared to other birds, is striking enough that it was known even then.

In occult circles, distinctions are sometimes made between crows and ravens. In mythology and folklore as a whole, crows tend to be symbolic more of the spiritual aspect of death, or the transition of the spirit into the afterlife, whereas ravens tend more often to be associated with the negative (physical) aspect of death. However, few if any individual mythologies or folklores make such a distinction, and there are ample exceptions. Another reason for this distinction is that while crows are typically highly social animals, ravens do not seem to congregate in large numbers anywhere but:

- Near carrion where they meet seemingly by chance, or

- At cemeteries, where large numbers sometimes live together, even though carrion there is no more available (and probably less attainable) than any road or field.

Among Neopagans, crows are often thought to be highly psychic and are associated with the element of ether or spirit, rather than the element of air as with most other birds. This may in part be due to the long-standing occult tradition of associating the color black with "the abyss" of infinite knowledge (ashka), or perhaps also to the more modern occult belief that wearing the "color" black aids in psychic ability, as it absorbs more electromagnetic energy, since surfaces appear black by absorbing all frequencies in the visible spectrum, reflecting no color.

According to the Bible (Leviticus 11:15), crows are not kosher.

Compendium of Materia Medica states that crows are kind birds that feed their old and weakened parents; this is often cited as a fine example of filial piety.

In Chinese mythology, they believed that the world at one time had ten suns that were caused by 10 crows. The effect was devastating to the crops and nature, so they sent in their greatest archer Houyi to shoot down 9 crows and spare only one. Also in China, crows commonly symbolize bad luck, probably due to the color black.

Gods and goddesses associated with crows and ravens

A very incomplete list of gods and goddesses associated with crows and ravens includes the eponymous Pacific Northwest Native figures Raven and Crow; the ravens Hugin and Munin, who accompany the Norse god Odin; the Celtic goddesses the Mórrígan and/or the Badb (sometimes considered separate from Mórrígan); and Shani, a Hindu god who travels astride a crow.

In Buddhism, the Dharmapala (protector of the Dharma) Mahakala is represented by a crow in one of his physical/earthly forms. Avalokiteśvara/Chenrezig, who is reincarnated on Earth as the Dalai Lama, is often closely associated with the crow because it is said that when the first Dalai Lama was born, robbers attacked the family home. The parents fled and were unable to get to the infant Lama in time. When they returned the next morning expecting the worst, they found their home untouched, and a pair of crows were caring for the Dalai Lama. It is believed that crows heralded the birth of the First, Seventh, Eighth, Twelfth, and Fourteenth Lamas, the latter being the current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso. Crows are mentioned often in Buddhism, especially Tibetan disciplines.

In Greek mythology, it was believed that when the crows gave bad news to the goddess Athena, she flew into a rage, and cursed their feathers to be black.

In Hinduism, it is believed that people who died will take food and offerings through a variety of crows called "Bali kākka." Every year people whose parents or relatives died will offer food to crows as well as cows on the Shradha day.

Systematics

The genus was originally described by Linnaeus in his eighteenth–century work Systema Naturae (Linäe and Wheeler 1766).

The type species is the common raven (Corvus corax); others named in the same work include the carrion crow (C. corone), the hooded crow (C. cornix), the rook (C. frugilegus) and the jackdaw (C. monedula).

There is not any good systematic approach to the genus at present. Generally, it is assumed that the species from a geographical area are more closely related to each other than to other lineages, but this is not necessarily correct. For example, while the carrion/collared/house crow complex is certainly closely related to each other, the situation is not at all clear regarding the Australian/Melanesian species. Furthermore, as many species are similar in appearance, determining actual range and characteristics can be very difficult, such as in Australia where the five (possibly six) species are almost identical in appearance.

Species

Australian and Melanesian species

- Australian Raven C. coronoides

- Forest Raven C. tasmanicus

- Relict Raven C. (t.) boreus

- Little Crow C. bennetti

- Little Raven C. mellori

- Torresian Crow C. orru

- New Caledonian Crow C. moneduloides

- Long-billed Crow C. validus

- White-billed Crow C. woodfordi

- Bougainville Crow C. meeki

- Brown-headed Crow C. fuscicapillus

- Grey Crow C. tristis

- New Ireland Crow, Corvus sp. (prehistoric)

New Zealand species

- Chatham Islands Raven, C. moriorum (prehistoric)

- New Zealand Raven, C. antipodum (prehistoric)

Pacific island species

- Mariana Crow, C. kubaryi

- Hawaiian Crow or ‘Alala C. hawaiiensis (extinct in the wild, formerly C. tropicus)

- High-billed Crow, C. impluviatus (prehistoric)

- Robust Crow, C. viriosus (prehistoric)

Tropical Asian species

- Slender-billed Crow C. enca

- Piping Crow C. typicus

- Banggai Crow C. unicolor (possibly extinct)

- Flores Crow C. florensis

- Collared Crow C. torquatus

- Daurian Jackdaw C. dauricus

- House Crow C. splendens

- Large-billed Crow C. macrorhynchos

- Jungle Crow C. (m.) levaillantii

Eurasian and North African species

- Brown-necked Raven C. ruficollis

- Somali Crow or Dwarf Raven C. edithae

- Fan-tailed Raven C. rhipidurus

- Jackdaw C. monedula

- Rook C. frugilegus

- Hooded Crow C. cornix

- Mesopotamian Crow, C. (c.) capellanus

- Carrion Crow C. corone

- Carrion Crow (Eastern subspecies) C. (c.) orientalis

- Corvus larteti (fossil: Late Miocene of France, or C Europe?)

- Corvus pliocaenus (fossil: Late Pliocene –? Early Pleistocene of SW Europe)

- Corvus antecorax (fossil: Late Pliocene/Early – Late Pleistocene of Europe; may be subspecies of Corvus corax

- Corvus betfianus (fossil)

- Corvus praecorax (fossil)

- Corvus simionescui (fossil)

- Corvus fossilis (fossil)

- Corvus moravicus (fossil)

- Corvus hungaricus (fossil)

Holarctic species

- Common Raven C. corax

- Pied Raven, C. c. varius morpha leucophaeus (an extinct color variant)

North and Central American species

- American Crow C. brachyrhynchos

- Chihuahuan Raven C. cryptoleucus

- Fish Crow C. ossifragus

- Northwestern Crow C. caurinus

- Tamaulipas Crow C. imparatus

- Sinaloan Crow C. sinaloae

- Jamaican Crow C. jamaicensis

- White-necked Crow C. leucognaphalus

- Palm Crow C. palmarum

- Cuban Crow C. nasicus

- Puerto Rican Crow C. pumilis (prehistoric; possibly a subspecies of C. nasicus/palmarum)

- Corvus galushai (fossil: Big Sandy Late Miocene of Wickieup, USA)

- Corvus neomexicanus (fossil: Late Pleistocene of Dry Cave, USA)

Tropical African species

- Cape Crow C. capensis

- Pied Crow C. albus

- Somali Crow or Dwarf Raven C. edithae

- Thick-billed Raven C. crassirostris

- White-necked Raven C. albicollis

In addition to the prehistoric forms listed above, some extinct chronosubspecies have been described. These are featured under the respective species accounts.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Animal Planet (Television network), and Blackbirch Press (AP and BP). 2003. Extreme thinkers. Planet's most extreme. Detroit: Blackbirch Press.

- Barker, F.K., A. Cibois, P. Schikler, J. Feinstein, and J. Cracraft. 2004. Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation. PNAS. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- Gill, B. J. 2003. Osteometry and systematics of the extinct New Zealand Ravens (Aves: Corvidae: Corvus). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 1(1): 43-58.

- Goodwin, D. and R. Gillmor. 1977. Crows of the world. St. Lucia, Q.: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 0702210153.

- Hasson, O. 2007. Bait-fishing in crows. Orenhasson.com. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- Linnäe, Carl von, and Alwyne Wheeler. 1766. Caroli a Linné ... Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tome I. Holmiae: impensis direct. Laurentii Salvii. ISBN 0565011324.

- McGowan, K. J. 2002. Frequently asked questions about crows. What is the difference between a crow and a raven?. Kevin J. McGowan home page: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- Rincon, P. 2005. Crows and jays top bird IQ scale. BBC News. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- Simpson, D.P. 1979. Cassell's Latin-English, English-Latin dictionary. London: Cassell. ISBN 0304522570.

- von Bayern, A.M.P., S. Danel, A.M.I. Auersperg, B. Mioduszewska, and A. Kacelnik. 2018. Compound tool construction by New Caledonian crows Scientific Reports, 8(1). Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- Wilcox, Carl. 2020. Cornish Chough A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry by James Parker. Retrieved Mary 4, 2021.

- Worthy, T.H., and Richard N. Holdaway. 2002. The Lost World of the Moa: Prehistoric Life of New Zealand. Life of the past. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253340349.

External links

All links retrieved January 11, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.