Crimean War

The Crimean War lasted from March 28, 1853 until April 1, 1856 and was fought between Imperial Russia on one side and an alliance of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the Second French Empire, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and to some extent the Ottoman Empire on the other.

The majority of the conflict took place on the Crimean peninsula in the Black Sea. Britain's highest medal for valour, The Victoria Cross (VC) was created after the war (January 29, 1856) to honor the bravery of 111 individuals during the conflict. Officers or enlisted men (and now women) can both receive this honor. Queen Victoria reflecting on her own reign a year before her death, saw the war in terms of helping "the rather weak Turks against the Russians. We also didn't want the Russians getting too strong, so this action served us well in two ways," she said. Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone detested the Turks, and was critical of Benjamin Disraeli's leniency towards them. During World War I, the same "rather weak Turks" were a formidable enemy.

Britain was at the height of her power, and tended to see policing the world as her task. In more modern parlance, the war might be referred to as a pre-emptive strike. It may have been the last war that some people regarded as a gentleman's' game, part of the "great game" which was not a game but an enterprise in which lives were lost. The General who was responsible for the disastrous charge of the Light Brigade, Lord Cardigan (1797-1868) had purchased his commissions, a practice that was stopped after the War. He had paid £40,000 for his commission. The British feared Russian expansion but they, not Russia, fired the first shot. The only positive aspect of the war was the emergence of the Nursing profession, due to the work of Florence Nightingale.

The war

Beginning of the war

In the 1840s, Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston and other British leaders expressed fears of Russian encroachment upon India and Afghanistan, and advocated finding an opportunity to weaken this threat. This was famously called the "great game," a phrase attributed to British spy, Captain Arthur Conolly (1807-1842) In the 1850s, a pretext was found in the cause of protecting Catholic holy places in Palestine. Under treaties negotiated during the eighteenth century, France was the guardian of Roman Catholics in the Ottoman Empire, while Russia was the protector of Orthodox Christians. For several years, however, Catholic and Orthodox monks had disputed possession of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. During the early 1850s, the two sides made demands which the Sultan could not possibly satisfy simultaneously. In 1853, the Ottoman Sultan adjudicated in favor of the French, despite the vehement protestations of the local Orthodox monks.

The Tsar of Russia, Nicholas I dispatched a diplomat, Prince Aleksandr Sergeyevich Prince Menshikov, on a special mission to the Porte (by which title the Ottoman Sultan was often referred). By previous treaties, the Sultan, Abd-ul-Mejid I, was committed "to protect the Christian religion and its Churches," but Menshikov attempted to negotiate a new treaty, under which Russia would be allowed to interfere whenever it deemed the Sultan's protection inadequate. At the same time, however, the British government of Prime Minister George Hamilton-Gordon sent Stratford Canning, 1st Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe, who learned of Menshikov's demands upon arriving in Istanbul. Through skillful diplomacy, Lord Stratford convinced the Sultan to reject the treaty, which compromised the independence of the Turks. Benjamin Disraeli blamed Aberdeen and Stratford's actions for making war inevitable, thus starting the process by which Aberdeen would be forced to resign for his role in starting the war. Shortly after he learned of the failure of Menshikov's diplomacy, the Tsar marched his armies into Moldavia and Wallachia (Ottoman principalities in which Russia was acknowledged as a special guardian of the Orthodox Church), using the Sultan's failure to resolve the issue of the Holy Places as a pretext. Nicholas believed that the European powers would not object strongly to the annexation of a few neighboring Ottoman provinces, especially given Russian involvement in suppressing the Revolutions of 1848.

When the Tsar sent his troops into Moldavia and Wallachia (the "Danubian Principalities"), Great Britain, seeking to maintain the security of the Ottoman Empire, sent a fleet to the Dardanelles, where it was joined by another fleet sent by France. At the same time, however, the European powers hoped for a diplomatic compromise. The representatives of the four neutral Great Powers—Great Britain, France, Austria and Prussia—met in Vienna, where they drafted a note which they hoped would be acceptable to Russia and Turkey. The note met with the approval of Nicholas I; it was, however, rejected by Abd-ul-Mejid I, who felt that the document's poor phrasing left it open to many different interpretations. Great Britain, France, and Austria were united in proposing amendments to mollify the Sultan, but their suggestions were ignored in the Court of Saint Petersburg. Great Britain and France set aside the idea of continuing negotiations, but Austria and Prussia did not believe that the rejection of the proposed amendments justified the abandonment of the diplomatic process. The Sultan proceeded to war, his armies attacking the Russian army near the Danube. Nicholas responded by dispatching warships, which destroyed the entire Ottoman fleet at the battle of Sinop on 30 November 1853, thereby making it possible for Russia to land and supply its forces on the Turkish shores fairly easily. The destruction of the Turkish fleet and the threat of Russian expansion alarmed both Great Britain and France, who stepped forth in defense of the Ottoman Empire. In 1853, after Russia ignored an Anglo-French ultimatum to withdraw from the Danubian principalities, Great Britain and France declared war.

Peace attempts

Nicholas presumed that in return for the support rendered during the Revolutions of 1848, Austria would side with him, or at the very least remain Neutral. Austria, however, felt threatened by the Russian troops in the nearby Danubian Principalities. When Great Britain and France demanded the withdrawal of Russian forces from the Principalities, Austria supported them; and, though it did not immediately declare war on Russia, it refused to guarantee its neutrality. When, in the summer of 1854, Austria made another demand for the withdrawal of troops, Russia feared that Austria would enter the war.

Though the original grounds for war were lost when Russia withdrew its troops from the Danubian Principalities, Great Britain, and France failed to cease hostilities. Determined to address the Eastern Question by putting an end to the Russian threat to the Ottoman Empire, the allies proposed several conditions for the cessation of hostilities, including:

- a demand that Russia was to give up its protectorate over the Danubian Principalities

- it was to abandon any claim granting it the right to interfere in Ottoman affairs on the behalf of the Orthodox Christians;

- the Straits Convention of 1841 was to be revised;

- all nations were to be granted access to the Danube River.

When the Tsar refused to comply with the Four Points, the Crimean War commenced.

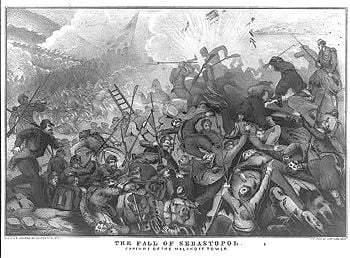

The siege of Sevastopol

The following month, though the immediate cause of war was withdrawn, allied troops landed in the Crimea and besieged the city of Sevastopol, home of the Tsar's Black Sea fleet and the associated threat of potential Russian penetration into the Mediterranean Sea.

The Russians had to scuttle their ships and used the naval cannons as additional artillery, and the ships' crews as marines. During the battle the Russians lost four 110- or 120-gun 3-decker ships of the line, twelve 84-gun 2-deckers and four 60-gun frigates in the Black Sea, plus a large number of smaller vessels. Admiral Nakhimov was mortally wounded in the head by a sniper shot, and died on June 30, 1855. The city was captured in September 1855.

In the same year, the Russians besieged and occupied]] the Turkish fortress of Kars.

Azov Campaign and the siege of Taganrog

In spring 1855, the allied British-French commanders decided to send an expedition corps into the Azov Sea to undermine Russian communications and supplies to besieged Sevastopol. On May 12, 1855 British-French war ships entered the Kerch Strait and destroyed the coast battery of the Kamishevaya Bay. On May 21, 1855 the gunboats and armed steamers attacked the seaport of Taganrog, the most important hub in terms of its proximity to Rostov on Don and due to vast resources of food, especially bread, wheat, barley, and rye that were amassed in the city after the breakout of Crimean War that put an end to its exportation.

The Governor of Taganrog, Yegor Tolstoy (1802–1874), and lieutenant-general Ivan Krasnov refused the ultimatum, responding that Russians never surrender their cities. The British-French squadron began bombardment of Taganrog during 6.5 hours and landed 300 troops near the Old Stairway in the downtown Taganrog, who were thrown back by Don Cossacks and volunteer corps.

In July 1855, the allied squadron tried to go past Taganrog to Rostov on Don, entering the Don River through the Mius River. On July 12, 1855 the H.M.S. Jasper grounded near Taganrog thanks to a fisherman, who repositioned the buoys into shallow waters. The cossacks captured the gunboat with all of its guns and blew it up. The third siege attempt was made August 19-31, 1855, but the city was already fortified and the squadron could not approach too close for landing operations. The allied fleet left the Gulf of Taganrog on September 2, 1855, with minor military operations along Azov Sea coast continuing until late fall 1855.

Baltic Theater

The Baltic was a forgotten theater of the war. The popularization of events elsewhere has overshadowed the overarching significance of this theater, which was close to the Russian capital. From the beginning the Baltic campaign turned into a stalemate. The outnumbered Russian Baltic Fleet confined its movements to the areas around fortifications. At the same time British and French commanders Sir Charles Napier and Parseval-Deschènes, although they led the largest fleet assembled since the Napoleonic wars, considered Russian coastal fortifications, especially the Kronstadt fortress, too well defended to engage and limited their actions to blockade of Russian trade and small raids on less protected parts of the coast of the Grand Duchy of Finland.

Russia was dependent on imports for both the domestic economy and the supply of her military forces and the blockade seriously undermined the Russian economy. The raiding allied British and French fleets destroyed forts on the Finnish coast including Bomarsund on the Åland Islands and Fort Slava. Other such attacks were not so successful, and the poorly planned attempts to take Gange, Ekenäs, Kokkola (Gamla-Karleby), and Turku (Åbo) were repulsed.

The burning of tar warehouses and ships in Oulu (Uleåborg) and Raahe (Brahestad) led to international criticism, and in Britain, a Mr. Gibson demanded in the House of Commons that the First Lord of the Admiralty explain a system which carried on a great war by plundering and destroying the property of defenseless villagers. By autumn, the Allies' fleet left the Baltic for the White Sea, where they shelled Kola and the Solovki. Their attempt to storm Arkhangelsk proved abortive, as was the siege of Petropavlovsk in Kamchatka.

In 1855, the Western Allied Baltic Fleet tried to destroy heavily defended Russian dockyards at Sveaborg outside Helsinki. More than 1,000 enemy guns tested the strength of the fortress for two days. Despite the shelling, the sailors of the 120-gun ship Russia, led by Captain Viktor Poplonsky, defended the entrance to the harbor. The Allies fired over twenty thousand shells but were unable to defeat the Russian batteries. A massive new fleet of more than 350 gunboats and mortar vessels was prepared, but before the attack was launched, the war ended.

Part of the Russian resistance was credited to the deployment of newly created blockade mines. Modern naval mining is said to date from the Crimean War: "Torpedo mines, if I may use this name given by Fulton to self-acting mines underwater, were among the novelties attempted by the Russians in their defenses about Cronstadt and Sebastopol," as one American officer put it in 1860.

Final phase and the peace

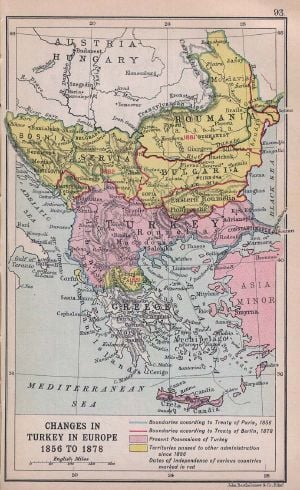

Peace negotiations began in 1856 under Nicholas I's successor, Alexander II of Russia. Under the ensuing Treaty of Paris, the "Four Points" plan proposed earlier was largely adhered to; most notably, Russia's special privileges relating to the Danubian Principalities were transferred to the Great Powers as a group. In addition, warships of all nations were perpetually excluded from the Black Sea, once the home to the Russian fleet (which, however, had been destroyed in the course of the war). Furthermore, the Tsar and the Sultan agreed not to establish any naval or military arsenal on the coast of that sea. The Black Sea clauses came at a tremendous disadvantage to Russia, for it greatly diminished the naval threat it posed to the Turks. Moreover, all the Great Powers pledged to respect the independence and territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire.

The Treaty of Paris stood until 1871, when France was crushed by Prussia in the Franco-Prussian War. Whilst Prussia and several other German states united to form a powerful German Empire, the Emperor of France, Napoleon III, was deposed to permit the formation of a Third French Republic. During his reign (which began in 1852), Napoleon III, eager for the support of Great Britain, had opposed Russia over the Eastern Question. Russian interference in the Ottoman Empire, however, did not in any significant manner threaten the interests of France. Thus, France abandoned its opposition to Russia after the establishment of a Republic. Encouraged by the decision of the French, and supported by the German minister Otto, Fürst von Bismarck, Russia denounced the Black Sea clauses of the treaty agreed to in 1856. As Great Britain alone could not enforce the clauses, Russia once again established a fleet in the Black Sea.

The Crimean War caused a mass exodus of Crimean Tatars towards the Ottoman lands, resulting in massive depopulation in the peninsula.

Characteristics of the war

The war became infamously known for military and logistical incompetence, epitomized by the Charge of the Light Brigade which was immortalized in Tennyson's poem. Cholera undercut French preparations for the siege of Sevastopol (1854), and a violent storm on the night of November 14, 1854 wrecked nearly 30 vessels with their precious cargoes of medical supplies, food, clothing, and other necessaries. The scandalous treatment of wounded soldiers in the desperate winter that followed was reported by war correspondents for newspapers, prompting the work of Florence Nightingale and introducing modern nursing methods.

Amongst the new techniques used to treat wounded soldiers, a primitive form of ambulances were used for the first time during this conflict.

The Crimean War also introduced the first tactical use of railways and other modern inventions such as the telegraph. The Crimean War is also credited by many as being the first modern war, employing trenches and blind artillery fire (gunners often relied on spotters rather than actually being on the battlefield). The use of the Minié ball for shot coupled with the rifling of barrels greatly increased Allied rifle range and damage.

The Crimean War occasioned the introduction of hand rolled "paper cigars"—cigarettes—to French and British troops, who copied their Turkish comrades in using old newspaper for rolling when their cigar-leaf rolling tobacco ran out or dried and crumbled.

It has been suggested that the Russian defeat in the Crimean War may have been a factor in the emancipation of Russian serfs by the Czar, Alexander II, in 1861.

The British army abolished the sale of military commissions, which allowed untrained gentry to purchase rank, as a direct result of the disaster at the Battle of Balaclava.

Major events of the war

- Some action also took place on the Russian Pacific coast, Asia Minor, the Baltic Sea, and White Seas

- The roots of the war's causes lay in the existing rivalry between the British and the Russians in other areas such as Afghanistan (The Great Game). Conflicts over control of holy places in Jerusalem led to aggressive actions in the Balkans, and around the Dardanelles.

- Major battles

- Destruction of the Ottoman fleet at Sinop - November 30, 1853;

- The Battle of Alma - September 20, 1854

- Siege of Sevastopol (1854) (more correctly, "Sevastopol") - September 25, 1854 to September 8, 1855

- The Battle of Balaclava - October 25, 1854 during which the infamous Charge of the Light Brigade took place under Lord Cardigan, when 673 British cavalry charged into a valley against Russian artillery deployed on both sides of the Valley.

- The Battle of Inkerman - November 5, 1854;

- Battle of Eupatoria, February 17, 1855

- Battle of Chernaya River (aka "Traktir Bridge") - August 25, 1855.

- Siege of Kars, June to November 28, 1855

- It was the first war where electric Telegraphy started to have a significant effect, with the first "live" war reporting to The Times by William Howard Russell, and British generals' reduced independence of action from London due to such rapid communications. Newspaper readership informed public opinion in the United Kingdom and France as never before.

Berwick-Upon-Tweed

There is a rather charming but apocryphal story, recently repeated on the BBC comedy programme, QI, that goes that when the UK joined the war, Great Britain, Ireland, Berwick-upon-Tweed and all British Dominions declared war. Berwick-upon-Tweed had been long disputed by England and Scotland, and hence was often treated as a separate entity. When the war ended, Berwick was accidentally left out of the text of the peace treaty. The Mayor of Berwick-upon-Tweed was subsequently visited by an official of the Soviet Union in 1966 to negotiate a peace settlement, declaring that "Russians can now sleep safely," (Berwick-upon-Tweed).

See also

- Florence Nightingale

- Timothy (tortoise), naval mascot.

- Anglo-Russian War (1807-1812)

- Leo Tolstoy wrote a few short sketches on the Siege of Sebastobol, collected in The Stebastobol Sketches. The stories detail the lives of the Russian soldiers and citizens in Sebastobol during the siege. Because of this work, Tolstoy has been called the world's first war correspondent.

- Jasper Fforde's Thursday Next novels, including The Eyre Affair, are set an alternate 1985 England where the Crimean War is still being fought.

- Beryl Bainbridge's novel Master Georgie is set in the Crimean War.

- George MacDonald Fraser's novel Flashman at the Charge (1986) is also set in the Crimean War.

- Stephen Baxter's novel Anti-Ice starts with the siege of Sebastopol, which is shortened dramatically by a new Anti-Ice weapon. The book asks the question—what if nuclear weapons had existed in Victorian times?

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bamgart, Winfried. The Crimean War, 1853-1856. London: Arnold Publishers, 2000. ISBN 034061465X

- Ponting, Clive. The Crimean War. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004. ISBN 0701173904

- Pottinger Saab, Anne. The Origins of the Crimean Alliance. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1997. ISBN 0813906997

- Rich, Norman. Why the Crimean War: A Cautionary Tale. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070522553

- Royle, Trevor. Crimea: The Great Crimean War, 1854-1856. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1403964165

- Schroeder, Paul W. Austria, Great Britain, and the Crimean War: The Destruction of the European Concert. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1972. ISBN 0801407427

- Wetzel, David. The Crimean War: A Diplomatic History. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985. ISBN 0880330864

Additional works

- Hamley, Edward Bruce, Sir. 1824-1893. The War in the Crimea. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1971. ISBN 0837150094

- Kinglake, Alexander William. 1809-1891. The Invasion of the Crimea. New York: AMS Press, 1972. 9 v. ISBN 0404037100

- Marx, Karl 1818-1883. The Eastern Question, 1853-56. translated by E. M. and E. Aveling, New York: A. M. Kelley, 1969. ISBN 0678005672

- Russell, William Howard, Sir. 1820-1907. The War in the Crimea, 1854-56. Russell’s dispatches from the Crimea, 1854-1856. Edited by Nicolas Bentley. New York: Hill and Wang, 1967.

External links

All links retrieved January 11, 2024.

- Loading and Firing British Muskets in the Crimean War 1854-1856

- Immediate causes of the War detailed in context.

- Punch Sketches on Crimean War

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.