Copyright

|

| Intellectual property law |

| Rights |

| Authors' rights · Intellectual property · Copyright Database right · Indigenous intellectual property Industrial design rights · Geographical indication Patent · Related rights · Trademark Trade secret · Utility model |

| Related topics |

| Fair use · Public domain Trade name |

Copyright is the exclusive right given to the creator of a creative work which may be in a literary, artistic, or musical form, to reproduce the work. It is intended to protect the original expression of an idea in the form of a creative work, but not the idea itself. These rights frequently include reproduction, control over derivative works, distribution, public performance, and moral rights such as attribution. Copyright is usually for a limited time, with the default length being the life of the author plus either 50 or 70 years.

Copyright has developed into a concept that has a significant effect on nearly every modern industry, including not just literary work, but also forms of creative work such as sound recordings, films, photographs, computer software, and architecture. The appropriate use of copyright protects the rights of the individual creator who is then responsible to exercise good stewardship over the created work, including allowing it to be available to the public to experience and appreciate.

Overview

Copyright is the exclusive right given to the creator of a creative work to reproduce the work, usually for a limited time.[1] The creative work may be in a literary, artistic or musical form. Copyright is intended to protect the original expression of an idea in the form of a creative work, but not the idea itself. In order to be eligible for copyright, the work may be required to be “fixed in a tangible medium of expression.”[2]

Generally, a copyright expires 50 or 70 years after the creator's death, depending on the jurisdiction. Some countries require certain copyright formalities to establishing copyright, others recognize copyright in any completed work, without formal registration. A copyright is subject to limitations based on public interest considerations, such as the fair use doctrine in the United States.

History

Background

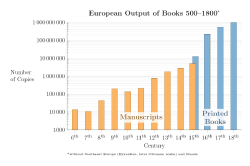

The concept of copyright developed after the printing press came into use in Europe[3] fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.[4] The printing press made it much cheaper to produce works, but as there was initially no copyright law, anyone could buy or rent a press and print any text. Popular new works were immediately re-set and re-published by competitors, so printers needed a constant stream of new material. Fees paid to authors for new works were high, and significantly supplemented the incomes of many academics.[5]

Printing brought profound social changes. The rise in literacy across Europe led to a dramatic increase in the demand for reading matter.[3] Prices of reprints were low, so publications could be bought by poorer people, creating a mass audience. In German-speaking areas, most publications were academic papers, and most were scientific and technical publications, often autodidactic practical instruction manuals on topics such as dike construction. After copyright law became established (in 1710 in England and Scotland, and in the 1840s in German-speaking areas) the low-price mass market vanished, and fewer, more expensive editions were published.[5]

Copyright laws allow products of creative human activities, such as literary and artistic production, to be preferentially exploited and thus incentivized. Different cultural attitudes, social organizations, economic models, and legal frameworks are seen to account for why copyright emerged in Europe and not, for example, in Asia. In the Middle Ages in Europe, there was generally a lack of any concept of literary property due to the general relations of production, the specific organization of literary production and the role of culture in society. The latter refers to the tendency of oral societies, such as that of Europe in the medieval period, to view knowledge as the product and expression of the collective, rather than to see it as individual property. However, with copyright laws, intellectual production comes to be seen as a product of an individual, with attendant rights. The most significant point is that patent and copyright laws support the expansion of the range of creative human activities that can be commodified. This parallels the ways in which capitalism led to the commodification of many aspects of social life that earlier had no monetary or economic value per se.[6]

National copyrights

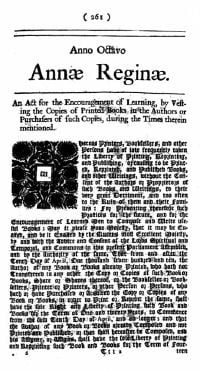

The concept of copyright first developed in England. In reaction to the printing of "scandalous books and pamphlets," the English Parliament passed the Licensing of the Press Act 1662,[3] which required all intended publications to be registered with the government-approved Stationers' Company, giving the Stationers the right to regulate what material could be printed.[7]

Often seen as the first real copyright law, the 1709 British Statute of Anne, which came into force in 1710, provided legislation to protect copyrights (but not authors' rights). It gave the publishers rights for a fixed period, after which the copyright expired.[8] The Copyright Act of 1814 extended more rights for authors but did not protect British works from being reprinted in the US. The Berne International Copyright Convention of 1886 finally provided protection for authors among the countries who signed the agreement, although the US did not join the Berne Convention until 1989.[9]

In the US, the Constitution protects the rights of authors and the legislature, Congress, can create national copyright laws but must exercise their power within the scope of the Constitution. Modeled on the Statute of Anne, Congress enacted the Copyright Act of 1790. While the national law protected authors’ published works, authority was granted to the states to protect authors’ unpublished works. These two protections exist today: protection by the state for unpublished work, subsequent protection by federal law for published work.[9]

Congress enacted an updated law in 1909, which was later determined to be flawed and was subsequently replaced by the 1976 Copyright Act. This act expanded the items that were eligible for protection, including literary, music, dramatic, pictorial/sculptural works, motion pictures, sound recordings, and choreographic works. The original length of copyright in the United States was 14 years, and it had to be explicitly applied for. If the author wished, they could apply for a second 14‑year monopoly grant, but after that the work entered the public domain, so it could be used and built upon by others. The 1976 act extended the copyright protection to life plus 50 years. One final change was that it “codified a fair use exception to copyright.” With these changes in place, the US was in a better position to join the Berne Convention, extending copyright protections internationally.[9]

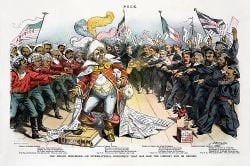

International copyright treaties

Copyright laws are standardized somewhat through international conventions such as the Berne Convention and Universal Copyright Convention. These multilateral treaties have been ratified by nearly all countries, and international organizations such as the European Union or World Trade Organization require their member states to comply with them. The regulations of the Berne Convention are incorporated into the World Trade Organization's TRIPS agreement (1995), thus giving the Berne Convention effectively near-global application.[10]

The 1886 Berne Convention first established recognition of copyrights among sovereign nations, rather than merely bilaterally. Under the Berne Convention, copyrights for creative works do not have to be asserted or declared, as they are automatically in force at creation: an author need not "register" or "apply for" a copyright in countries adhering to the Berne Convention.[11] As soon as a work is "fixed," that is, written or recorded on some physical medium, its author is automatically entitled to all copyrights in the work, and to any derivative works unless and until the author explicitly disclaims them, or until the copyright expires. The Berne Convention also resulted in foreign authors being treated equivalently to domestic authors, in any country signed onto the Convention. Specially, for educational and scientific research purposes, the Berne Convention provides the developing countries issue compulsory licenses for the translation or reproduction of copyrighted works within the limits prescribed by the Convention. This was a special provision that had been added at the time of 1971 revision of the Convention, because of the strong demands of the developing countries.

The UK signed the Berne Convention in 1887 but did not implement large parts of it until 100 years later with the passage of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The United States did not sign the Berne Convention until 1989.[12]

The United States and most Latin American countries instead entered into the Buenos Aires Convention in 1910, which required a copyright notice on the work (such as all rights reserved), and permitted signatory nations to limit the duration of copyrights to shorter and renewable terms.[12]

The Universal Copyright Convention was drafted in 1952 as another less demanding alternative to the Berne Convention, and ratified by nations such as the Soviet Union and developing nations.

Obtaining protection

Ownership

Typically, the owner of a copyright is the person who created the work, namely the author, artist, musical composer, and so forth.[13] However, there are several exceptions. The original holder of the copyright may be the employer of the author rather than the author himself if the work is a "work for hire." For example, in English law the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 provides that if a copyrighted work is made by an employee in the course of that employment, the copyright is automatically owned by the employer which would be a "Work for Hire." Also, when two or more authors prepare a work then a case of joint authorship can be made if they intended to combine their contributions into inseparable or interdependent parts. The work is then considered joint work, and the authors are considered joint copyright owners.[13]

Eligible works

Copyright may apply to a wide range of creative, intellectual, or artistic forms, or "works.. Specifics vary by jurisdiction, but these can include poems, theses, fictional characters plays and other literary works, motion pictures, choreography, musical compositions, sound recordings, paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, computer software, radio and television broadcasts, and industrial designs. Graphic designs and industrial designs may have separate or overlapping laws applied to them in some jurisdictions.[14]

Copyright does not cover ideas and information themselves, only the form or manner in which they are expressed.[15] For example, the copyright to a Mickey Mouse cartoon restricts others from making copies of the cartoon or creating derivative works based on Disney's particular anthropomorphic mouse, but does not prohibit the creation of other works about anthropomorphic mice in general, so long as they are different enough to not be judged copies of Disney's.[15] Note additionally that Mickey Mouse is not copyrighted because characters cannot be copyrighted; rather, the animated short film Steamboat Willie is copyrighted and Mickey Mouse, as a character in that copyrighted work, is afforded protection.

Originality

Typically, a work must meet minimal standards of originality in order to qualify for copyright. The "threshold of originality" is a concept in copyright law that is used to assess whether a particular work can be copyrighted, distinguishing works that are sufficiently original to warrant copyright protection from those that are not. In this context, "originality" refers to "coming from someone as the originator/author" (insofar as it somehow reflects the author's personality), rather than "never having occurred or existed before" (which would amount to the protection of something new, as in patent protection).

Different countries impose different tests, although generally the requirements are low. In Australia and the United Kingdom it has been held that a single word is insufficient to comprise a copyright work. However, single words or a short string of words can sometimes be registered as a trademark instead.

Copyright law recognizes the right of an author based on whether the work actually is an original creation, rather than based on whether it is unique; two authors may own copyright on two substantially identical works, if it is determined that the duplication was coincidental, and neither was copied from the other.

Registration

The purpose of copyright registration is to place on record a verifiable account of the date and content of the work in question, so that in the event of a legal claim, or case of infringement or plagiarism, the copyright owner can produce a copy of the work from an official government source.

In all countries where the Berne Convention standards apply, copyright is automatic, and need not be obtained through official registration with any government office. Once an idea has been reduced to tangible form, for example by securing it in a fixed medium (such as a drawing, sheet music, photograph, a videotape, or a computer file), the copyright holder is entitled to enforce his or her exclusive rights.[11] However, while registration is not required to exercise copyright, in jurisdictions where the laws provide for registration, it serves as prima facie evidence of a valid copyright and enables the copyright holder to seek statutory damages and attorney's fees.[16]

Fixing

The Berne Convention allows member countries to decide whether creative works must be "fixed" to enjoy copyright. Article 2, Section 2 of the Berne Convention states: "It shall be a matter for legislation in the countries of the Union to prescribe that works in general or any specified categories of works shall not be protected unless they have been fixed in some material form." Some countries do not require that a work be produced in a particular form to obtain copyright protection. For instance, Spain, France, and Australia do not require fixation for copyright protection. The United States and Canada, on the other hand, require that most works must be "fixed in a tangible medium of expression" to obtain copyright protection.[17] U.S. law requires that the fixation be stable and permanent enough to be "perceived, reproduced or communicated for a period of more than transitory duration." Similarly, Canadian courts consider fixation to require that the work be "expressed to some extent at least in some material form, capable of identification and having a more or less permanent endurance."[17]

Copyright notice

Before 1989, United States law required the use of a copyright notice, consisting of the copyright symbol (©, the letter C inside a circle), or the word "Copyright," followed by the year of the first publication of the work and the name of the copyright holder.[18] Several years may be noted if the work has gone through substantial revisions. The proper copyright notice for sound recordings of musical or other audio works is a sound recording copyright symbol (℗, the letter P inside a circle), which indicates a sound recording copyright, with the letter P indicating a "phonorecord." In addition, the phrase All rights reserved was once required to assert copyright, but that phrase is now legally obsolete.

In 1989 the United States enacted the Berne Convention Implementation Act, amending the 1976 Copyright Act to conform to most of the provisions of the Berne Convention. As a result, the use of copyright notices has become optional to claim copyright, because the Berne Convention makes copyright automatic.

Items on the Internet generally have some sort of copyright attached to them, whether they are watermarked, signed, or have any other sort of indication of the copyright.[19]

Enforcement

Copyrights are generally enforced by the holder in a civil law court, but there are also criminal infringement statutes in some jurisdictions. While central registries are kept in some countries which aid in proving claims of ownership, registering does not necessarily prove ownership, nor does the fact of copying (even without permission) necessarily prove that copyright was infringed. Criminal sanctions are generally aimed at serious counterfeiting activity, but became more commonplace as copyright collectives such as the RIAA increasingly target the file sharing home Internet user.

In most jurisdictions the copyright holder must bear the cost of enforcing copyright. This will usually involve engaging legal representation, administrative or court costs. In light of this, many copyright disputes are settled by a direct approach to the infringing party in order to settle the dispute out of court.

Copyright infringement

Copyright infringement (colloquially referred to as "piracy") is the use of works protected by copyright law without permission for a usage where such permission is required, thereby infringing certain exclusive rights granted to the copyright holder, such as the right to reproduce, distribute, display, or perform the protected work, or to make derivative works. Copyright holders routinely invoke legal and technological measures to prevent and penalize copyright infringement.

For a work to be considered to infringe upon copyright, its use must have occurred in a nation that has domestic copyright laws or adheres to a bilateral treaty or established international convention such as the Berne Convention or WIPO Copyright Treaty. Improper use of materials outside of legislation is deemed "unauthorized edition," not copyright infringement.[20]

Copyright infringement disputes are usually resolved through direct negotiation, a notice and take down process, or litigation in civil court. Egregious or large-scale commercial infringement, especially when it involves counterfeiting, is sometimes prosecuted via the criminal justice system. Shifting public expectations, advances in digital technology, and the increasing reach of the Internet have led to such widespread, anonymous infringement that copyright-dependent industries now focus less on pursuing individuals who seek and share copyright-protected content online, and more on expanding copyright law to recognize and penalize, as indirect infringers, the service providers and software distributors who are said to facilitate and encourage individual acts of infringement by others.

Estimates of the actual economic impact of copyright infringement vary widely and depend on many factors. Nevertheless, copyright holders, industry representatives, and legislators have long characterized copyright infringement as piracy or theft.

Rights granted

The basic right when a work is protected by copyright is that the holder may determine and decide how and under what conditions the protected work may be used by others. This includes the right to decide to distribute the work for free. This part of copyright is often overseen. The phrase "exclusive right" means that only the copyright holder is free to exercise those rights, and others are prohibited from using the work without the holder's permission. Copyright is sometimes called a "negative right", as it serves to prohibit certain people (e.g., readers, viewers, or listeners, and primarily publishers and would be publishers) from doing something they would otherwise be able to do, rather than permitting people (e.g., authors) to do something they would otherwise be unable to do. In this way it is similar to the unregistered design right in English law and European law. The rights of the copyright holder also permit him/her to not use or exploit their copyright, for some or all of the term.

According to World Intellectual Property Organization, copyright protects two types of rights: Economic rights allow right owners to derive financial reward from the use of their works by others. Moral rights allow authors and creators to take certain actions to preserve and protect their link with their work. Where economic rights allow right owners to derive financial reward from the use of their works by others, the moral rights allow authors and creators to take certain actions to preserve and protect their link with their work.[1]

Economic rights

With any kind of property, its owner may decide how it is to be used, and others can use it lawfully only if they have the owner's permission, often through a license. The owner's use of the property must, however, respect the legally recognized rights and interests of other members of society. So the owner of a copyright-protected work may decide how to use the work, and may prevent others from using it without permission. National laws usually grant copyright owners exclusive rights to allow third parties to use their works, subject to the legally recognized rights and interests of others.[1] Most copyright laws state that authors or other right owners have the right to authorize or prevent certain acts in relation to a work. Right owners can authorize or prohibit:

- reproduction of the work in various forms, such as printed publications or sound recordings;

- distribution of copies of the work;

- public performance of the work;

- broadcasting or other communication of the work to the public;

- translation of the work into other languages; and

- adaptation of the work, such as turning a novel into a screenplay.

Moral rights

Moral rights are concerned with the non-economic rights of a creator. They protect the creator's connection with a work as well as the integrity of the work. Moral rights are accorded to individual authors and in many national laws they remain with the authors even after the authors have transferred their economic rights. This means that even where, for example, a film producer or publisher owns the economic rights in a work, in many jurisdictions the individual author continues to have moral rights.[1]

The Berne Convention, in Article 6bis, requires its members to grant authors the following rights:

- the right to claim authorship of a work (sometimes called the right of paternity or the right of attribution); and

- the right to object to any distortion or modification of a work, or other derogatory action in relation to a work, which would be prejudicial to the author's honor or reputation (sometimes called the right of integrity).

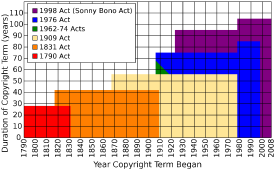

Duration

Copyright subsists for a variety of lengths in different jurisdictions. The length of the term can depend on several factors, including the type of work (such as musical composition or novel), whether the work has been published, and whether the work was created by an individual or a corporation.

International treaties establish minimum terms for copyrights, but individual countries may enforce longer terms than those.[21] In most of the world, the default length of copyright is the life of the author plus either 50 or 70 years. In the United States, the term for most existing works is a fixed number of years after the date of creation or publication. Under most countries' laws, copyrights expire at the end of the calendar year in which they would otherwise expire. If the author has been dead more than 70 years, the work is in the public domain in most, but not all, countries.

The length and requirements for copyright duration are subject to change by legislation, and since the early twentieth century there have been a number of adjustments made in various countries, which can make determining the duration of a given copyright somewhat difficult. For example, the United States used to require copyrights to be renewed after 28 years to stay in force, and formerly required a copyright notice upon first publication to gain coverage. In Italy and France, there were post-wartime extensions that could increase the term by approximately six years in Italy and up to about 14 in France. Many countries have extended the length of their copyright terms (sometimes retroactively).

In the United States, all books and other works published before 1923 have expired copyrights and are in the public domain. In addition, works published before 1964 that did not have their copyrights renewed 28 years after first publication year also are in the public domain. The great majority of these works, including 93 percent of the books, were not renewed after 28 years and are therefore in the public domain.[22] Books originally published outside the US by non-Americans are exempt from this renewal requirement, if they are still under copyright in their home country. In 1998, the length of a copyright in the United States was increased by 20 years under the Copyright Term Extension Act. This legislation was strongly promoted by corporations which had valuable copyrights which otherwise would have expired, and has been the subject of substantial criticism on this point.[23]

Limitations and exceptions

In many jurisdictions, copyright law makes exceptions to these restrictions when the work is copied for the purpose of commentary or other related uses. US copyright does NOT cover names, title, short phrases, or Listings (such as ingredients, recipes, labels, or formulas).[24] However, there are protections available for certain areas copyright does not cover – such as trademarks and patents.

Idea–expression dichotomy and the merger doctrine

The idea–expression divide differentiates between ideas and expression, and states that copyright protects only the original expression of ideas, and not the ideas themselves. This principle, first clarified in the 1879 case of Baker v. Selden, has since been codified by the Copyright Act of 1976 at 17 U.S.C. § 102(b).

The first-sale doctrine and exhaustion of rights

Copyright law does not restrict the owner of a copy from reselling legitimately obtained copies of copyrighted works, provided that those copies were originally produced by or with the permission of the copyright holder. It is therefore legal, for example, to resell a copyrighted book or CD. In the United States this is known as the first-sale doctrine, and was established by the courts to clarify the legality of reselling books in second-hand bookstores.

Some countries may have parallel importation restrictions that allow the copyright holder to control the aftermarket. This may mean for example that a copy of a book that does not infringe copyright in the country where it was printed does infringe copyright in a country into which it is imported for retailing. The first-sale doctrine is known as exhaustion of rights in other countries and is a principle which also applies, though somewhat differently, to patent and trademark rights. It is important to note that the first-sale doctrine permits the transfer of the particular legitimate copy involved. It does not permit making or distributing additional copies.

In addition, copyright, in most cases, does not prohibit one from acts such as modifying, defacing, or destroying his or her own legitimately obtained copy of a copyrighted work, so long as duplication is not involved. However, in countries that implement moral rights, a copyright holder can in some cases successfully prevent the mutilation or destruction of a work that is publicly visible.

Fair use and fair dealing

Copyright does not prohibit all copying or replication. In the United States, the fair use doctrine, codified by the Copyright Act of 1976 as 17 U.S.C. Section 107, permits some copying and distribution without permission of the copyright holder or payment to same. The statute does not clearly define fair use, but instead gives four non-exclusive factors to consider in a fair use analysis. Those factors are:

- the purpose and character of one's use

- the nature of the copyrighted work

- what amount and proportion of the whole work was taken, and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.[25]

EU copyright laws recognize the right of EU member states to implement some national exceptions to copyright. Examples of those exceptions are:

- photographic reproductions on paper or any similar medium of works (excluding sheet music) provided that the rightholders receives fair compensation,

- reproduction made by libraries, educational establishments, museums or archives, which are non-commercial

- archival reproductions of broadcasts,

- uses for the benefit of people with a disability,

- for demonstration or repair of equipment,

- for non-commercial research or private study

- when used in parody

In the United Kingdom and many other Commonwealth countries, a similar notion of fair dealing was established by the courts or through legislation.

In the United States the AHRA (Audio Home Recording Act Codified in Section 10, 1992) prohibits action against consumers making noncommercial recordings of music, in return for royalties on both media and devices plus mandatory copy-control mechanisms on recorders. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act prohibits the manufacture, importation, or distribution of devices whose intended use, or only significant commercial use, is to bypass an access or copy control put in place by a copyright owner.[14]

Accessible copies

It is legal in several countries including the United Kingdom and the United States to produce alternative versions (for example, in large print or braille) of a copyrighted work to provide improved access to a work for blind and visually impaired persons without permission from the copyright holder.[26][27]

Public domain

Copyright, like other intellectual property rights, is subject to a statutorily determined term. Once the term of a copyright has expired, the formerly copyrighted work enters the public domain and may be used or exploited by anyone without obtaining permission, and normally without payment. Public domain also includes works for which copyright has been forfeited, expressly waived, or may be inapplicable.

Public domain works should not be confused with works that are publicly available. Works posted in the internet, for example, are publicly available, but are not generally in the public domain. Copying such works may therefore violate the author's copyright.

Transfer, assignment and licensing

A copyright, or aspects of it (for example, reproduction alone, all but moral rights), may be assigned or transferred from one party to another.[28] For example, a musician who records an album will often sign an agreement with a record company in which the musician agrees to transfer all copyright in the recordings in exchange for royalties and other considerations. The creator (and original copyright holder) benefits, or expects to, from production and marketing capabilities far beyond those of the author. In the digital age of music, music may be copied and distributed at minimal cost through the Internet; however, the record industry attempts to provide promotion and marketing for the artist and his or her work so it can reach a much larger audience. A copyright holder need not transfer all rights completely, though many publishers will insist. Some of the rights may be transferred, or else the copyright holder may grant another party a non-exclusive license to copy or distribute the work in a particular region or for a specified period of time.

Copyright may also be licensed.[28] Some jurisdictions may provide that certain classes of copyrighted works be made available under a prescribed statutory license (for example, musical works in the United States used for radio broadcast or performance). This is also called a compulsory license, because under this scheme, anyone who wishes to copy a covered work does not need the permission of the copyright holder, but instead merely files the proper notice and pays a set fee established by statute (or by an agency decision under statutory guidance) for every copy made.[28] Failure to follow the proper procedures would place the copier at risk of an infringement suit. Because of the difficulty of following every individual work, copyright collectives or collecting societies and performance rights organizations (such as ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC) have been formed to collect royalties for hundreds (thousands and more) works at once. Though this market solution bypasses the statutory license, the availability of the statutory fee still helps dictate the price per work collective rights organizations charge, driving it down to what avoidance of procedural hassle would justify.

Free licenses

Copyright licenses known as open or free licenses seek to grant several rights to licensees, either for a fee or not. Free in this context is not as much of a reference to price as it is to freedom. What constitutes free licensing has been characterized in a number of similar definitions, including the Free Software Definition, the Debian Free Software Guidelines, the Open Source Definition, and the Definition of Free Cultural Works. Further refinements to these definitions have resulted in categories such as copyleft and permissive. Common examples of free licenses are the GNU General Public License, BSD licenses, and some Creative Commons licenses.

Terms of use have traditionally been negotiated on an individual basis between copyright holder and potential licensee. Copyright-holder stipulations may include whether he or she is willing to allow modifications to the work, whether he or she permits the creation of derivative works, and whether he or she is willing to permit commercial use of the work.[29]

Criticism

Criticism of copyright, perhaps outright anti-copyright sentiment, is a dissenting view of the current state of copyright law or copyright as a concept. Critical groups often discuss philosophical, economical, or social rationales of such laws and the laws' implementations, the benefits of which they claim do not justify the policy's costs to society. They advocate for changing the current system, though different groups have different ideas of what that change should be. Some call for remission of the policies to a previous state—copyright once covered few categories of things and had shorter term limits—or they may seek to expand concepts like Fair Use that allow permissionless copying. Others seek the abolition of copyright itself.

Some sources are critical of particular aspects of the copyright system. This is known as a debate over copynorms. Particularly to the background of uploading content to internet platforms and the digital exchange of original work, there is discussion about the copyright aspects of downloading and streaming, the copyright aspects of hyperlinking and framing.

Concerns are often couched in the language of digital rights, digital freedom, database rights, open data or censorship.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Understanding Copyright and Related Rights World Intellectual Property Organization, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ↑ Rich Stim, Copyright Basics FAQ Copyright and Fair Use, Stanford University Libraries. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 L. Ray Patterson, Copyright in Historical Perspective (Vanderbilt University Press, 1968, ISBN 978-0826513731).

- ↑ Ronan Deazley, Martin Kretschmer, and Lionel Bently (eds.), Privilege and Property: Essays on the History of Copyright (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2010, ISBN 978-1906924188).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Frank Thadeusz, No Copyright Law: The Real Reason for Germany's Industrial Expansion? Spiegel International, August 18, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ↑ Ronald V. Bettig, Copyrighting Culture: The Political Economy of Intellectual Property (Routledge, 2019, ISBN 978-0367315221).

- ↑ Karen Nipps, Cum privilegio: Licensing of the Press Act of 1662 The Library Quarterly 84(4) (2014):494–500. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ↑ Ronan Deazley, Rethinking Copyright: History, Theory, Language (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008, ISBN 978-1847209443).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Sandra Day O'Connor, Copyright Law from an American Perspective Irish Jurist 37 (2002):16–22.

- ↑ Abbe Brown, Smita Kheria, Jane Cornwell, and Marta Iljadica, Contemporary Intellectual Property: Law and Policy (Oxford University Press, 2019, ISBN 978-0198799801).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works Article 5 World Intellectual Property Organization. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 International Copyright Relations of the United States Circular 38A, United States Copyright Office, August 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rich Stim, Copyright Ownership: Who Owns What? Copyright and Fair Use, Stanford University Libraries. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Peter K. Yu, Intellectual Property and Information Wealth: Issues and Practices in the Digital Age (Praeger Publishers, 2009, ISBN 978-0275988845).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Simon Stokes, Art and Copyright (Hart Publishing, 2001, ISBN 978-1841132259).

- ↑ Subject Matter and Scope of Copyright Copyright Law of the United States. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Fixation Module 3: The Scope of Copyright Law. Berkman Klein Center. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ↑ Copyright Act of 1976, Pub.L. 94 -553, 90 Stat. 2541, § 401(a) (19 October 1976).

- ↑ Astra Taylor, The People's Platform:Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age (Metropolitan Books, 2014, ISBN 978-0805093568).

- ↑ Lynette Owen, Piracy Learned Publishing 14(1) (2001):67–70. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ↑ David Nimmer, Copyright: Sacred Text, Technology, and the DMCA (Springer, 2002, ISBN 978-9041188762).

- ↑ Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States, Cornell University Library. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ↑ Lawrence Lessig, Copyright's First Amendment, 48 UCLA L. Rev. 1057, 1065 (2001)

- ↑ Works Not Protected by Copyright, Circular 33 U.S. Copyright Office, September 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ↑ US CODE: Title 17,107. Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use Legal Information Institute. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ↑ Chapter 1 – Circular 92 U.S. Copyright Office. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ↑ Copyright (Visually Impaired Persons) Act 2002 comes into force Royal National Institute of Blind People, January 1, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 WIPO, WIPO Guide on the Licensing of Copyright and Related Rights (World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), 2004, ISBN 978-9280512717).

- ↑ Richard E. Rubin, Foundations of Library and Information Science (Neal-Schuman Publishers, Inc., 2015, ISBN 978-0838913703).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bettig, Ronald V. Copyrighting Culture: The Political Economy of Intellectual Property. Routledge, 2019. ISBN 978-0367315221

- Brown, Abbe, Smita Kheria, Jane Cornwell, and Marta Iljadica. Contemporary Intellectual Property: Law and Policy. Oxford University Press, 2019. ISBN 978-0198799801

- Deazley, Ronan. Rethinking Copyright: History, Theory, Language. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1847209443

- Deazley, Ronan, Martin Kretschmer, and Lionel Bently (eds.). Privilege and Property: Essays on the History of Copyright (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2010. ISBN 978-1906924188

- Patterson, L. Ray. Copyright in Historical Perspective. Vanderbilt University Press. 1968. ISBN 978-0826513731

- Rubin, Richard E. Foundations of Library and Information Science. Neal-Schuman Publishers, Inc., 2015. ISBN 978-0838913703

- Stokes, Simon. Art and Copyright. Hart Publishing, 2001. ISBN 978-1841132259

- Taylor, Astra. The People's Platform:Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age. Metropolitan Books, 2014. ISBN 978-0805093568

- WIPO, WIPO Guide on the Licensing of Copyright and Related Rights. World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), 2004. ISBN 978-9280512717

- Yu, Peter K. Intellectual Property and Information Wealth: Issues and Practices in the Digital Age. Praeger Publishers, 2009. ISBN 978-0275988845

External links

All links retrieved January 7, 2024.

- Copyright Berne Convention: Country List List of the members of the Berne Convention for the protection of literary and artistic works

- Copyright World Intellectual Property Organization

- USA

- U.S. Copyright Office

- Copyright Law of the United States U.S. Copyright Office

- Compendium of Copyright Practices U.S. Copyright Office

- Early Copyright Records From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- What Is a Copyright?

- UK

- Copyright: detailed information UK Intellectual Property Office

- Copyright Law fact sheet a concise introduction to UK Copyright legislation

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.