Bulgarian Empire

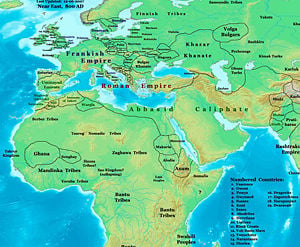

Bulgarian Empire is a term used to describe two periods in the medieval history of Bulgaria, during which it acted as a key regional power in Europe in general and in Southeastern Europe in particular, often rivaling Byzantium. The two "Bulgarian Empires" are not treated as separate entities, but rather as one state restored after a period of Byzantine rule over its territory.

The "First Bulgarian Empire" was established as a result of an expansion of Old Great Bulgaria to the territory south of Danube River, and is usually described as having lasted between 681 C.E. (when its existence was acknowledged by Byzantium by means of a peace treaty) and 1018 C.E., when it was subjugated by the Byzantine Empire. It gradually reached its cultural and territorial apogee in the ninth century and early tenth century under Boris I and Simeon the Great, when it developed into the cultural and literary center of Slavic Europe, as well as becoming one of the largest states in Europe. The medieval Bulgarian state was restored as the "Second Bulgarian Empire" after a successful uprising of two nobles from Tarnovo, Asen, and Peter, in 1185, and existed until it was conquered during the Ottoman invasion of the Balkans in the late fourteenth century, with the date of its subjugation usually given as 1396. (The last Bulgarian territory to fall under Ottoman domination was Sozopol, in 1453.)

Under Ivan Asen II in the first half of the thirteenth century it gradually recovered much of its former power, though this did not last long due to internal problems and foreign invasions. Memory of this period of their history, and pride in their national heritage and identity, combined with new notions of the nation-state in the early nineteenth century to inspire the movement for independence from Ottoman rule. This is known as the National awakening of Bulgaria. The imperial period was represented as a highpoint of Bulgarian achievement and its Christian identity was also stressed, over-and-against that of the Muslim Turks.

After a failed uprising in April 1876, independence was achieved de facto in 1878 following the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878. Bulgaria's complete independence was recognized by the Ottomans in 1908. Throughout much of its history, this region was a border or frontier zone between different forms of Christianity (Orthodox and Catholic) then between Christianity and Islam. During the imperial period, a substantial Jewish population also lived in Bulgaria (where under Ottoman rule they took refuge after expulsion from parts of the Christian world), as did Bogomils. Historical reconstruction, such as that used to inspire the national reawakening, can either stress such a zone's role as a buttress, or as a bridge, between civilizations, cultures and religions. The intellectual leaders of the national reawakening tended to demonize the Muslim Turks although others stress a legacy of mutual understanding, co-existence and tolerance that provides an alternative account.[1]

First Bulgarian Empire

The First Bulgarian Empire was a medieval Bulgarian state founded in 632 C.E. in the lands near the Danube Delta and disintegrated in 1018 C.E. after its annexation to the Byzantine Empire. At the height of its power it spread between Budapest and the Black Sea and from the Dnieper river in modern Ukraine to the Adriatic. It was succeeded by the Second Bulgarian Empire, established in 1185. The official name of the country since its very foundation was Bulgaria.

The Empire played a major role in European politics was one of the strongest military powers of its time. In 717-718. the coalition of Byzantines and Bulgarians decisively defeated the Arabs in the siege of Constantinople thus saving Eastern Europe from the Muslim threat and later destroyed the Avar Khanate expanding its territory to the Pannonian Plain and the Tatra Mountains. Bulgaria served as an effective shield against the constant invasions of nomadic peoples from the east in the so called second wave of the Great Migration. Pechenegs and Cumans were stopped in north-eastern Bulgaria and after a decisive victory over the Magyars in 896 they were forced to retreat to an permanently settle down in Pannonia.

To the south in course of the Byzantine-Bulgarian Wars the Bulgarians incorporated most of Slavic-populated region of Thrace and Macedonia. After the annihilation of the Byzantine army in the battle of Anchialus in 917 the Byzantine Empire was on the edge of destruction.

The Bulgars brought new construction and battle techniques to Europe. The first Bulgarian cities were made of large monolith stones unlike the Roman brick-build fortresses. With an area of 27 km² the capital Pliska was among the largest towns in Europe. The Inner town had a sewerage and floor heating long before cities such as Paris and London. After the adoption of Christianity in 864 Bulgaria became the cultural center of Slavic Europe. Its leading cultural position was further consolidated with the invention of the Cyrillic alphabet in Preslav, which some credit to the Bulgarian scholar Clement of Ohrid. According to some historians the schools of Preslav and Ohrid were the second universities in Europe after the University of Constantinople.

Background

During the time of the late Roman Empire, the lands of present-day Bulgaria had been organized in several provinces—Scythia Minor, Moesia (Upper and Lower), Thrace, Macedonia (First and Second), Dacia (south of the Danube), Dardania, Rhodope, and Hemimont, and had a mixed population of Romanized Getae and Hellenized Thracians. During the Hunnic Invasions of Central and Eastern Europe, Turkic groups named Bulgars settled in the region. Several consecutive waves of Slavic migration throughout the sixth and the early seventh century led to the almost complete slavicisation of the region, at least linguistically.

The Bulgars

Little is known about the origins of the Bulgars that reached the Balkan peninsula in the seventh century (according to some sources even earlier) because during the ages the original Bulgars melted into the local population of what is nowadays Bulgaria.

The established theory is that the Bulgars are related to the Huns and originated in Central Asia but their ethnicity is not entirely clear. Clues for this can be found in the advanced calendar and system of government of the early Bulgars.

Nevertheless the so called "Hun theory" is still vehemently supported by some historians who base their thesis on a lot of existing documents and sources. In Nominalia of the Bulgarian khans, a late copy of an ancient document, is written that the first ruler of the Bulgars was Avitohol and the second Irnik. Irnik or Ernakh is the name of Attila's youngest son therefore some historians believe that Avitohol was no other than Attila the Hun.

It is assumed that the Bulgars were governed by hereditary khans. The only similar title found so far is kanasubigi and it was used by only four of the Bulgarian rulers, namely Krum, Omurtag, Malamir, and Presian, which were respectively a grandfather, son, grandson, and a nephew of Malamir, and after them the title disappears. Other similar but non-kingly titles were attested among Bulgarian noble class and these are kavkan (vicekhan), tarkan, and boritarkan. Starting from there (if there was a vicekhan (kavkhan) so there was a khan, too) the scholars assume the title khan for the early Bulgarian leader. Later inscriptions speak of archonts (a Greek title) and knyaze (a Slavic title). There were several (probably more than 100) aristocratic families whose members, called boila (boyars) who bore military titles and formed a governing class. The religion of the Bulgars is also obscure but it is supposed that it was monotheistic, worshiping the Turkic Sky god Tangra. There is only one mentioning of Tangra in the eighth century inscription near the Madara Rider. All other sources simply talk about Bog, the Slavic and Aryan word for God. More confusingly some Bulgar rulers, renowned for their persecution of Christians were depicted with Christian state symbols. There is a theory that Bulgars were Arians (an early Christian sect). On the top of that, early Bulgar sacred places featured the plan of two concentric squares, typical to Zoroastrian temples.[2]

The migration of Bulgars to the European continent started as early as the second century C.E. when branches of Bulgars settled on the plains between the Caspian and the Black Sea. Between 351 and 389 C.E., some of these crossed the Caucasus and settled in Armenia. They were eventually assimilated by the Armenians.

Swept by the Hunnish wave at the beginning of the fourth century C.E., other numerous Bulgarian tribes broke loose from their settlements in central Asia to migrate to the fertile lands along the lower valleys of the Donets and the Don rivers and the Azov seashore. Some of these remained for centuries in their new settlements, whereas others moved on with the Huns towards Central Europe, settling in Pannonia.

In the sixth and seventh century, the Bulgars formed an independent state, often called Great Bulgaria, between the lower course of the Danube to the west, the Black and the Azov Seas to the south, the Kuban river to the east, and the Donets river to the north. The capital of the state was Phanagoria, on the Azov.

The pressure from peoples further east (such as the Khazars) led to the dissolution of Great Bulgaria in the second half of the seventh century. One Bulgar tribe migrated to the confluence of the Volga and Kama Rivers in what is now Tatarstan, Russia (see Volga Bulgaria). They converted to Islam in the beginning in the tenth century and maintained an independent state until the thirteenth century. Smaller Bulgar tribes seceded in Pannonia and in Italy, northwest of Naples, while other Bulgars sought refuge with the Lombards. Another group of Bulgars remained in the land north of the Black and the Azov Seas. They were, however, soon subdued by the Khazars. These Bulgars converted to Judaism in the ninth century, along with the Khazars, and were eventually assimilated.

Establishment of the Bulgarian state

There are two different dates for the year of establishment of present-day Bulgaria, based upon two different interpretations of history.

Yet another Bulgar tribe, led by Khan Asparuh, moved westward, occupying today's southern Bessarabia. After a successful war with Byzantium in 680 C.E., Asparuh's khanate conquered Moesia and Dobrudja and was recognized as an independent state under the subsequent treaty signed with the Byzantine Empire in 681. The same year is usually regarded as the year of the establishment of present-day Bulgaria.

Another theory is that Great Bulgaria, although it suffered a major territory loss from the Khazars, managed to defeat them in the early 670s. Khan Asparuh, the successor of Khan Kubrat, conquered Moesia and Dobrudja after the war with the Byzantine Empire in 680. This war ended with a peace treaty in 681. Therefore, according to some researchers, the year of establishment of present-day Bulgaria has to be considered 632, and not 681.

Establishing a firm foothold in the Balkans

After the decisive victory at Ongala in 680 the armies of the Bulgars and Slavs advanced to the south of the Balkan mountains, defeating again the Byzantines who were then forced to sign a humiliating peace treaty which acknowledged the establishment of a new state on the borders of the Empire. They were also to pay an annual tribute to Bulgaria. In the same time the war with the Khazars to the east continued and in 700 Asparough perished in battle with them. The Bulgars lost the territories to the east of the Dnester river but managed to hold the lands to the west. The Bulgars and the Slavs signed a treaty according to which the head of the state became the Khan of the Bulgars who had also the obligation to defend the country against the Byzantine, while the Slavic leaders gained considerable autonomy and had to protect the northern borders along the Carpathian mountains against the Avars.

Asparough's successor, Tervel helped the deposed Byzantine Emperor Justinian II to regain his throne in 705. In return, he was given the area Zagore in northern Thrace which was the first expansion of the country to the south of the Balkan mountains. However, three years later Justinian tried to take it back by force but his army was defeated at Anchialus. In 716, Tervel signed a trade agreement with Byzantium. During the siege of Constantinople in 717-718, he sent 50,000 troops to help the besieged city. In the decisive battle the Bulgarians massacred around 30,000 Arabs[3] and Tervel was called The saviour of Europe by his contemporaries.

Internal instability and struggle for survival

In 753 died Khan Sevar who was the last scion of the Dulo clan. With his death the Khanate fell into a long political crisis during which the young country was on the verge of destruction. For just 15 years ruled 7 Khans who were all murdered. There were two main fractions; some nobles wanted uncompromising war against the Byzantines while others searched for a peaceful settlement of the conflict. That instability was used by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine V (745-775), who launched nine major campaigns aiming at the elimination of Bulgaria. In 763, he defeated the Bulgarian Khan Telets at Anchialus but the Byzantines were unable to advance further north. In 775 Khan Telerig, by tricking Constantine to reveal those loyal to him in the Bulgarian Court, executed all the Byzantine spies in the capital Pliska.[4] Under his successor Kardam, the war took a favorable turn after the great victory in the battle of Marcelae[5] in 792. The Byzantines were thoroughly defeated and forced once again to pay tribute to the Khans. As a result of the victory, the crisis was finally overwhelmed and Bulgaria entered the new century stable, stronger and consolidated.

Territorial expansion

Under the great Khan Krum (803-814), also known as Crummus and Keanus Magnus, Bulgaria expanded northwest and southwards, occupying the lands between middle Danube and Moldova, the whole territory of present-day Romania, Sofia in 809 and Adrianople (modern Odrin) in 813, and threatening Constantinople itself. Between 804 and 806 the Bulgarian armies thoroughly eliminated the Avar Khanate and a border with the Frankish Empire was established along the middle Danube. In 811 a large Byzantine army was decisively defeated in the battle of the Varbitsa Pass.[6] The Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus I was slain along with most of his troops. Krum immediately took the initiative and moved the war towards Thrace, defeating the Byzantines once more at Versinikia in 813. After a treacherous Byzantine attempt to kill the Khan during negotiations, Krum pillaged the whole of Thrace, seized Odrin and resettled its 10,000 inhabitants in "Bulgaria across the Danube." He made enhanced preparation to capture Constantinople: 5,000 iron-plated wagons were built to carry the siege equipment, the Byzantines even pleaded for help from the Frankish Emperor Louis the Pious. Due to the sudden death of the great Khan, however, the campaign was never launched. Khan Krum implemented law reform intending to reduce the poverty and to strengthen the social ties in his vastly enlarged state.

During the reign of Khan Omurtag (814-831), the northwestern boundaries with the Frankish Empire were firmly settled along the middle Danube by the 827 and magnificent palace, pagan temples, ruler's residence, fortress, citadel, water-main and bath were built in Bulgarian capital Pliska, mainly of stone and brick.

During the short reign of Malamir (831-836) the important city of Plovdiv was incorporated into the country. Under Khan Presian (836-852), the Bulgarians took most of Macedonia and the borders of the country reached the Adriatic and Aegean Seas. The Byzantine historians do not mention any resistance against the Bulgarian expansion in Macedonia which bring the conclusion that it was largely peaceful.

Merger of Bulgars and Slavs

It is assumed that The Bulgars were greatly outnumbered by the Slav population among whom they had settled. Between the seventh and the tenth centuries, the Bulgars were gradually absorbed by the Slavs, adopting a Bulgaro-South Slav language and converting to Christianity (of the Byzantine rite) under Boris I in 864. At that time the process of absorption of the remnants of the old Romanized Thracian population from south of the Danube had already been significant in the formation of this new ethnic group. Modern Bulgarians are normally considered to be of Southern Slavic origin, even though the Slavs were only one of the peoples that took part in the formation of their ethnicity. Some recent studies suggest that the Bulgars were much more numerous than originally thought. This theory is gaining more support amongst new Bulgarian historians.

Bulgaria under Boris I

The reign of Boris I (852-889) began with numerous setbacks. For ten years the country fought against the Byzantine and Eastern Frankish Empires, Great Moravia, the Croats and the Serbs forming several unsuccessful alliances and changing sides. In August 863 there was a period of 40 days of earthquakes and there was a lean year which caused famine throughout the country. To cap it all there was an incursion of locusts.

Christianization

In 864, the Byzantines under Michael III invaded Bulgaria on suspicions that Khan Boris I prepared to accept Christianity in accordance with the Western rites. Upon the news of the invasion, Boris I started negotiations for peace. The Byzantines returned some lands in Macedonia and their single demand was that he accept Christianity from Constantinople rather than Rome. Khan Boris agreed to that term and was baptized in September 865 assuming the name of his godfather, Byzantine Emperor Michael. The pagan title "Khan" was abolished and the title "Knyaz" assumed in its place. The reason for the conversion to Christianity, however, was not the Byzantine invasion. The Bulgarian ruler was indeed a man of vision and he foresaw that the introduction of a single religion would complete the consolidation of the emerging Bulgarian nation which was still divided on a religious basis. He also knew that his state was not fully respected by Christian Europe and its treaties could have been ignored by other signatories on religious basis.

The Byzantines' goal was to achieve with peace what they were unable to after two centuries of warfare: to slowly absorb Bulgaria through the Christian religion and turn it into a satellite state, as naturally, the highest posts in the newly founded Bulgarian Church were to be held by Byzantines who preached in the Greek language. Boris was well aware of that fact and after Constantinople refused to grant autonomy of the Bulgarian Church in 866 he sent a delegation to Rome declaring his desire to accept Christianity in accordance with the Western rites along with 115 questions to Pope Nicolas I. The Bulgarian ruler desired to take advantage of the rivalry between the Churches of Rome and Constantinople as his main goal was the establishment of an independent Bulgarian Church in order to prevent both the Byzantines and the Catholics from exerting influence in his lands through religion. The Pope's detailed answers to Boris' questions were delivered by two bishops heading a mission whose purpose was to facilitate the conversion of the Bulgarian people. However, Nicolas I and his successor Pope Adrian II also refused to recognize an autonomous Bulgarian Church which cooled the relations between the two sides but Bulgaria's shift towards Rome made the Byzantines much more conciliatory. In 870, at the Fourth Council of Constantinople, the Bulgarian Church was recognized as an Autonomous Eastern Orthodox Church under the supreme direction of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Creation of the Slavic Writing System

Although the Bulgarian Knyaz succeeded in securing an autonomous Church, its higher clergy and theological books were still Greek which impeded the efforts to convert the populace to the new religion. Between 860 and 863 the Byzantine monks of Slavic origin[7] Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius created the Glagolitic alphabet, the first Slavic alphabet by order of the Byzantine Emperor, who aimed to convert Great Moravia to Orthodox Christianity. However these attempts failed and in 886 their disciples Clement of Ohrid, Naum of Preslav and Angelarius, who were banished from Great Moravia, reached Bulgaria and were warmly welcomed by Boris I. The Bulgarian Knyaz commissioned the creation of two theological academies to be headed by the disciples where the future Bulgarian clergy was to be instructed in the local vernacular. Clement was sent to Ohrid in southwestern Bulgaria where he taught 3,500 pupils between 886 and 893. Naum established the literary school in the capital Pliska, moved later to the new capital Preslav. In 893, Bulgaria adopted the Glagolitic alphabet and Old Church Slavonic (Old Bulgarian) language as official language of the church and state and expelled the Byzantine clergy. In the early tenth century the Cyrillic alphabet was created at the Preslav Literary School.

The "Golden Age"

By the late ninth and the beginning of the tenth century, Bulgaria extended to Epirus and Thessaly in the south, Bosnia in the west and controlled the whole of present-day Romania and eastern Hungary to the north. A Serbian state came into existence as a dependency of the Bulgarian Empire and was later fully subordinated under the general and possibly Count of Sofia Marmais. Under Tsar Simeon I (Simeon the Great), who was educated in Constantinople, Bulgaria became again a serious threat to the Byzantine Empire and reached its greatest territorial extension. Simeon hoped to take Constantinople and fought a series of wars with the Byzantines throughout his long reign (893-927). The border close to the end of his rule reached Peloponnese in the south. Simeon styled himself "Emperor (Tsar) of the Bulgarians and Autocrat of the Greeks," a title which was recognized by the Pope, but not of course by the Byzantine Emperor nor the Ecumenical Patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Between 894 and 896, he defeated the Byzantines and their allies the Magyars in the so called "Trade War" because the pretext of the war was the shifting of the Bulgarian market from Constantinople to Solun. In the decisive battle of Bulgarophygon the Byzantine army was routed and the war ended with favorable for Bulgaria peace which was, however, often violated by Simeon. In 904 he captured Solun which was previously looted by the Arabs and returned it to the Byzantines only after Bulgaria received all Slavic-populated areas in Macedonia and 20 fortress in Albania including the important town Drach.

After the unrest in the Byzantine Empire that followed the death of Emperor Alexander in 913 Simeon invaded Byzantine Thrace but was persuaded to stop in return for official recognition of his Imperial title and marriage of his daughter to the infant Emperor Constantine VII.[8][9] After a plot in the Byzantine court Empress Zoe rejected the marriage and his title and both sides prepared for a decisive battle. By 917 Simeon broke every attempts of his enemy to form an alliance with the Magyars, the Pechenegs and the Serbs and Byzantines were forced to fight alone. On August 20, the two armies clashed at Anchialus in one of the greatest battles in the Middle Ages. The Byzantines suffered an unprecedented defeat leaving 70,000 killed on the battlefield. The pursuing Bulgarian forces defeated the reminder of the enemy armies at Katasyrtai.[10] However, Constantinople was saved by a Serb attack from the west; the Serbs were thoroughly defeated but that gave precious time for the Byzantine admiral and later Emperor Romanos Lakepanos to prepare the defense of the city. In the following decade the Bulgarians gained control of the whole Balkan peninsula with the exception of Constantinople and Pelopones.

Decline

After Simeon's death, however, Bulgarian power slowly declined. In a peace treaty in 927 the Byzantines officially recognized the Imperial title of his son Peter I and the Bulgarian Patriarchate. The peace with Byzantium did not bring prosperity to Bulgaria. In the beginning of his rule the new Emperor had internal problems and unrest with his brothers and in 930s was forced to recognize the independence of Rascia. The main blow came from the north: Between 934 and 965 the country suffered five Magyar invasions.[11] In 944, Bulgaria was attacked by the Pechenegs who looted the north eastern regions of the Empire. Under Peter I and Boris II the country was divided by the egalitarian religious teaching of the Bogomils.

In 968, the country was attacked by Kievan Rus, whose leader, Svyatoslav I, took Preslav and established his capital at Preslavets. Three years later, Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimiskes interfered into the struggle and defeated Svyatoslav at Dorostolon. After that, Boris II was deceived and solemnly dethroned at Constantinople and eastern Bulgaria was proclaimed a Byzantine protectorate.

Struggle for independence

After the Byzantine betrayal the lands to the west of the Iskar river remained free and the resistance against the Byzantines was headed by the Comitopuli brothers. By 976 the forth brother Samuil concentrated the whole power in his hands after the deaths of his eldest brothers. When the rightful heir to the throne, Roman, escaped from captivity in Constantinople, he was recognized for Emperor by Samuil in Vidin and the later remained the chief commander of the Bulgarian army. Brilliant general and good politician, he managed to turn the fortunes to the Bulgarians. The new Byzantine Emperor Basil II was decisively defeated in the battle of the Gates of Trajan in 986 and barely escaped. Five years later he eliminated the Serbian state. In 997, after the death of Roman who was the last from the Krum dynasty Samuil was proclaimed Emperor of Bulgaria. However, after 1001 the war turned in favor of the Byzantines who captured the old capitals Pliska and Preslav in the same year and from 1004 launched annual campaigns against Bulgaria. They were eased by a war between Bulgaria and the newly established Kingdom of Hungary 1003. In 1014 Emperor Basil II defeated the armies of Tsar Samuil in the Battle of Belasitsa and massacred thousands, acquiring the title "Bulgar-slayer" (Voulgaroktonos). He ordered 14,000 Bulgarian prisoners blinded and sent back to their country. At the sight of his returning armies Samuil suffered a heart attack and died. By 1018, the country had been mostly subjugated by the Byzantines.

Cultural development

Missionaries from Constantinople, Cyril and Methodius, devised the Glagolitic alphabet, which was adopted in the Bulgarian Empire around 886. The alphabet and the Old Bulgarian language gave rise to a rich literary and cultural activity centered around the Preslav and Ohrid Schools, established by order of Boris I in 886. In the beginning of tenth century, a new alphabet—the Cyrillic alphabet—was developed on the basis of Greek and Glagolitic cursive at the Preslav Literary School. According to an alternative theory, the alphabet was devised at the Ohrid Literary School by Saint Clement of Ohrid, a Bulgarian scholar and disciple of Cyril and Methodius. A pious monk and hermit St. Ivan of Rila (Ivan Rilski, 876-946), became the patron saint of Bulgaria. After 893 Preslav became the truly new Bulgarian capital.

During his reign Simeon gathered many scholars in his court who translated enormous number of books from Greek and wrote many new works. Among the most prominent figures were Constantine of Preslav, John Exarch, and Chernorizets Hrabar, who is believed by some historians to have been Simeon himself. The was intensive construction of churches and monasteries throughout the Empire including the Great Basilica in Pliska which was one of the biggest structures of the time with its length of 99 m and the splendid Golden Church in Preslav. The Bulgarian capital was also famous for its ceramics which adorned the public and religious buildings. Beautiful icons and church altars were made of special ceramic tiles. There were numerous goldsmith and silversmith workshops who produced fine jewelry.

Second Bulgarian Empire

The Second Bulgarian Empire (Bulgarian: Второ българско царство, Vtorо Balgarskо Tsartsvo) was a medieval Bulgarian state which existed between 1185 and 1396 (or 1422). A successor of the First Bulgarian Empire, it reached the peak of its power under Kaloyan and Ivan Asen II before gradually declining to be conquered by the Ottomans in the late fourteenth-early fifteenth century. It was succeeded by the Principality and later Kingdom of Bulgaria in 1878.

Up to 1256 the Second Bulgarian Empire was the dominant power in the Balkans. The Byzantines were defeated in several major battles and in 1205 the newly-established Latin Empire was crushed in the battle of Adrianople by Emperor Kaloyan. His nephew Ivan Asen II (1218-1241) destroyed the Despotate of Epiros and made Bulgaria a leading European power once again. However, in the late thirteenth century the Empire declined under the constant invasions of Tatars, Byzantines, Hungarians and internal instability and revolts. In the late fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth century the country was overrun by the Ottoman Turks who ruined Bulgaria's economy and infrastructure, depopulated large areas and killed the nobility.

Culturally the Bulgarian Empire was among the most advanced states in contemporary Europe. Despite the strong Byzantine influence, the Bulgarian artists and architects managed to create their own distinct style. Literature flourished in the fourteenth century and around 80 percent of the Bulgarian population was literate.

Background

The Byzantines ruled Bulgaria from 1018, when they conquered the First Bulgarian Empire, to 1185, although initially it was not fully integrated into the Byzantine Empire, for example preserving the existing tax levels and the power of the low-ranking nobility. The independent Bulgarian Orthodox Church was subordinated to the authority of the Ecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople, and the Bulgarian aristocracy and tsar's relatives were given various Byzantine titles and transferred to the Asian parts of the Empire. There were rebellions against Byzantine rule in 1040-41, the 1070s and the 1080s, but these failed.

Liberation

By the late twelfth century the Byzantines were in decline after a series of wars with the Hungarians and the Serbs. In 1185 Peter and Asen (described in some contemporary accounts to be of Cuman or Vlach origin) led a revolt against Byzantine rule and Peter declared himself Tsar Peter IV (also known as Theodore Peter), firmly claiming to inherit the authority of the First Bulgarian Empire. After little more than a year of warfare the Byzantines were forced to acknowledge Bulgaria's independence, though fighting continued. The peoples who took part in the rebellion and formed part of the new state certainly included Slavic-speaking Bulgarians and, alongside them, Cumans, Vlachs and Greeks: Peter styled himself "Tsar of the Bulgars, Greeks and Vlachs."

The war between 1185 and 1197

In the summer of 1185 a miraculous icon of Saint Dimitar of Solun was found in Tarnovo and the Asen brothers claimed that the saint had abandoned Solun in order to help the Bulgarian cause. That had a large psychological impact on the religious population. Between the autumn of 1185 and the spring of 1186 the whole northern Bulgaria with the exception of Varna was liberated. In the summer the Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelos managed to overcome the mountain passes and invaded Moesia. Asen retreated to the north of the Danube and after the Byzantines went back to Constantinople he returned with more Cuman auxiliaries and soon the war continued to the south in Thrace. A skillful general, Asen stroke swiftly and constantly harassed the larger Byzantine armies. After an unsuccessful siege of Lovech in 1187 the Byzantines were forced to plead for a truce. Three years later they were decisively defeated near Tryavna, Isaac II Angelos barely escaped leaving the Imperial crown and cross. In the next five years the Bulgarian held the initiative and reconquered more towns and castles in northern Thrace and Macedonia especially after the major victory at Arcadiopolis in 1194 and in 1196, the Byzantines were defeated at Serres but soon after that Asen was murdered by his cousin Ivanko incited by the Byzantines. He usurped the throne but could not stay in the capital which was besieged by Peter; fled to Byzantium and was made a governor of Plovdiv. However, only a year later Peter IV became victim of another plot and was succeeded by the youngest brother Kaloyan.

European power

Resurrected Bulgaria occupied the territory between the Black Sea, the Danube and Stara Planina, including a part of eastern Macedonia and the valley of the Morava. It also exercised influence over Wallachia and Moldova.

Kaloyan

Tsar Kaloyan (1197–1207) entered a union with the Papacy, thereby securing the recognition of his title of "Rex" although he desired to be recognized as "Emperor" or "Tsar." He waged wars on the Byzantine Empire and (after 1204) on the Knights of the Fourth Crusade, conquering large parts of Thrace, the Rhodopes, as well as the whole of Macedonia. He decisively defeated the newly created Latin Empire in the Battle of Adrianople (1205) and thus crushed its power in the very first year of its creation and prevented their influence on the larger parts of the Balkans. Their Emperor Baldwin I was captured in the battle and later died in captivity in Tarnovo. In the next year the Latins suffered another heavy defeat in the battle of Rusion. At first his struggle was supported by the Byzantine nobility but then they betrayed the Bulgarians and allied with the Crusaders. Kaloyan was infuriated and killed many Byzantines. He wanted to revenge for Samuil's 14,000 blinded soldiers and called himself Romanoktonos (Roman-slayer) as Basil II was called Bulgaroktonos (Bulgarian-slayer).

To the west and north-west he fought against the Hungarians and defeated them several times.

Ivan Asen II

After the death of Kaloyan during the reign of his cousin Boril (1207–1218), the country lost significant territories to Hungary, the Latin Empire and the Despotate of Epirus.

Under Ivan Asen II (1218–1241), Bulgaria once again became a European power, liberating the lost lands and occupying Odrin and Albania. In the beginning of his reign he peacefully regained Belgrade and Branicevo which were lost to Hungary and some lands from the Latin Empire. After the major success at Klokotnitsa in 1230 the Epirus Despotate became a vassal tributary to Bulgaria. In an inscription from Turnovo in 1230, he entitled himself "In Christ the Lord faithful Tsar and autocrat of the Bulgarians, son of the old Asen." The Bulgarian Orthodox Patriarchate was restored in 1235 with approval of all eastern Patriarchates, thus putting an end to the union with the Papacy. Ivan Asen II had a reputation as a wise and humane ruler, and opened relations with the Catholic west, especially Venice and Genoa, to diversify the trade of his country. The country enjoyed flourishing economy, trade relations were diversified and around 1235 Bulgaria had an organized Navy. In the last year of his reign he defeated the Tatars who attacked Bulgaria after their devastating raid in Hungary.

Decline

Under Ivan Asen II's successors, Bulgaria declined. The Mongols raided the Balkans in the early thirteenth century, devastating Bulgaria in 1242, and Bulgaria was forced to pay tribute to the Khans of the Golden Horde. After 1256, the Empire Nicaea annexed southern Macedonia, Rhodope mountains and part of Thrace. The Hungarian kingdom occupied the province of Belgrade. Gradually Bulgaria lost control and traditional significant political influence over Wallachia, where the power of the regional nobles was strengthened and subsequently were established local principalities. By the reign of Michael II Asen 1246–1256, Bulgaria had lost significant territories to its enemies without any major military disaster but because of the disloyal nobles who surrendered territories for personal enrichment. Under Constantine I Tikh the country lost northern and central Macedonia to Byzantium as well as Severin Banat to Hungary and the crisis drove to peasant war, raised by the swineherd Ivailo, who managed to sit on the Bulgarian throne from 1277 to 1280.

Ivailo achieved great military success against the external enemies: defeated the Byzantines in two major battles and temporarily drove away the Tatars from the northeastern parts of the Empire. However, he failed to cope with the aristocracy and was later killed. The Tatar hegemony continued to 1300, when after the death of Nogai Khan their khan Toktu ceded Bessarabia the new Bulgarian Emperor Theodore Svetoslav and stopped taking tribute. This had positive economic effect. During the reign of Theodore Svetoslav Bulgaria regained much of its former strength and prestige. After a successful war against Byzantium he signed peace with continued to his death in 1322.

Ivan Alexander and fall of Bulgaria

The withdrawal of the Mongols from Europe in the early fourteenth century stabilized the situation in the Balkans and Bulgaria reassumed something like its modern borders. But Bulgaria was threatened by the rising powers of Hungary to the north and Serbia to the west. In 1330 the Bulgarians under Michael III were heavily defeated by the Serbs at Velbuzhd, and some parts of the Empire came under Serbian sway. Under Ivan IV (Ivan Alexander), 1331–1371, Serbian threat was ended and the Byzantines were defeated at Rusokastro. The territorial expansion included the Rhodope mountains and several important towns on the Black Sea coast. This was a period known as Second Golden Age because of the thriving culture. Eventually after his death Bulgaria was left divided into rival states; one of the two largest ones was based at Veliko Turnovo and the other at Vidin, ruled by Ivan's two sons.

The two brothers and despot Dobrotitsa from the Principality of Carvuna did not make an attempt to unite and they were even engaged in a military conflict for Sofia. Weakened Bulgaria was thus no match for a new threat from the south, the Ottoman Turks, who crossed into Europe in 1354. In 1362 they captured Philippopolis (Plovdiv), and in 1382 they took Sofia. The Ottomans then turned their attention to the Serbs, whom they routed at Kosovo Pole in 1389. In 1393, the Ottomans occupied Turnovo after a three-month siege. It is thought that the south gate was opened from inside and so the Ottomans managed to enter the fortress. In the next year the Ottomans captured the Carvuna Principality and Nikopol—the last town of the Turnovo Tsardom—fell in 1395. Next year the Kingdom of Vidin was also occupied, bringing the Second Bulgarian Empire and Bulgarian independence to an end.

Administration

The supreme power in the country belonged to the Emperor. His official title was: "In Christ God faithful Emperor and Autocrat of all Bulgarians," which often included "Greeks." The most significant meaning was that he was Emperor of the whole Bulgarian people, even to those beyond the borders of the Empire. The legislative and executive powers were concentrated in his hands. If the heir of the ruler was under age, the regency was headed by the mother-Empress.

The Bolyar Counsel, called also Sinklit included the Great Bolyars and the Patriarch. Their task was to discuss important questions about the external and internal policy such as declaration of war, formation of alliance or signing peace. The last word always belonged to the Emperor. Sometimes Counsels with extended members were assembled, where the nobility, the clergy and "the other people" usually gathered to discuss condemnation of heresies: 1211, 1350, 1360. The only right the ordinary people had was to approve the decisions made by the nobility.

The main administrative unit in thirteenth-fourteenth centuries was hora (хорá) which replaced the komitat from the First Bulgarian Empire. Its governor was called Duke (Kefaliya) and was usually appointed by the Emperor; the hora was further divided into katepanikons (borrowed by Byzantium) which were ruled by Katepans, who were directly subordinated to the Dukes.

Economy

The Medieval Bulgarian economy did not differ much from the other Eastern European states and relied mainly on agriculture, mining, traditional crafts and trade.

Agriculture

The main agricultural regions of the country were the Danubian plain and Thrace. The most widespread grains were wheat, barley and millet. From the thirteenth century the importance of vegetables, orchards and grapes grew. The main wine-producing areas were the Black Sea coast, along the Struma, southern Macedonia. Livestock breeding was well developed. There were many sheep, pigs and cattle. The pastures were divided into two groups: winter pastures (valleys) and summer pastures (mountains). In the fourteenth century, apiculture and sericulture became profitable branches.

The dense forests were also divided into two types: woods for cutting and fenced forests in which cutting was banned.

Metallurgy and crafts

The twelfth-fourteenth centuries gave a strong impetus to metallurgy and mining. Bulgarian smiths produced hammers, pliers, axes, saws, looms; different arms and armors. In the thirteenth century Saxon miners, who made ore extracting more efficient and introduced new mining methods, arrived in western Bulgaria. They inhabited mainly the regions of Chiprovtsi and Kyustendil. There used to be gold mines in the Eastern Rhodopes.

About 50 different types of handicraft were known in Medieval Bulgaria, the most important being leather making, shoemaking, carpentry, weaving; production of food and drinks (bread, butter, cheese, wine). Vast quantity of catapults, battering-rams and other siege equipment were made, and the army had skilled siege engineers. The main centers were the capital Tarnovo, Cherven.

Culture

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries Bulgaria became a thriving cultural centre. The flowering of the Turnovo school of art was related to the construction of palaces and churches, to literary activity in the royal court and the monasteries, and to the development of handicrafts. Remarkable achievements of this school have been preserved down to this day: the murals of the Boyars' houses in Trapezitsa and Saint Forty Martyrs Church in Veliko Tarnovo, the Boyana Church (1259) and the Rock-hewn Churches of Ivanovo. Book illuminations also developed, examples include the Manasses Chronicle, the Tetraevangelia of Ivan Alexander and the Tomich Psalter. Many relics of Orthodox martyrs and saints were kept in the numerous churches in the capital Turnovo, which earned the capital the byname "second Constantinople."

Most of the architectural monuments from that period include churches, monasteries and fortresses. The Bulgarians usually built small churches with short doors to show humbleness and homage to God. They were often richly decorated with blind niches, various geometrical patterns from bricks, stone cubes, ceramics; while from the inside they were painted with marvelous frescoes which from the thirteenth century began to draw away from the canon and became realistic.

In the fourteenth century many new monasteries were built under the patronage of Ivan Alexander on the northern slopes of Stara Planina, especially in a area near the capital Tarnovo which became known as "Sveta Gora" (Holy Forest)—a name also used to refer to Mount Athos. The numerous monasteries across the Empire were the very centre of the cultural, educational and spiritual life of the Bulgarian society. After the mid fourteenth centuries, many monasteries began to build fortifications under the thread of Turk invasions, such as the famous Tower of Rely in the Rila monastery.

There used to be a perfectly organized defensive network of fortresses which consisted of several lines along the Danube, the Balkan mountains, the Rhodope, the coast. The main fortress was Turnovo. Other major castles included Vidin, Silistra, Cherven, Lovech, Sofia, Plovdiv, Lyutitsa, Ustra, and many others.

Legacy

The achievements of the Bulgarian Empire culturally, religiously and territorially were regarded as the highpoint of Bulgarian history in the nineteenth century when the national reawakening began to resurrect pride in Bulgaria's past in order to generate support for the independence struggle against the Ottomans. Inevitably, this contrasted Bulgaria's Christian legacy during the imperial period with Turkey's Muslim heritage, and chose to emphasize what was perceived as negative in the history of relations between the two, representing the totality of the story as one of oppression of Christians by Muslims. Other accounts tell a somewhat different story, in which the two communities, alongside the Jews, often if not always lived in harmony, with inter-marriage and cultural exchange. This choice of a negative account was dictated by historical and political circumstance. Lewis cites a fifteenth-century Jew writing to Jews in Europe and urging them to migrate to Turkey: "Is it not better for you to live under Muslims than Christians? Here every man may dwell at peace under his own vine and fig tree. Here you are allowed to wear the most precious garments. In Christendom, on the contrary, you dare not even venture to clothe your children red or blue—without exposing them to the insult of being beaten black and blue…[in Germany Jews] are pursued even unto death."[12] Lewis comments that Jewish reports on Turkish behavior and attitudes “are almost uniformly favorable.” On the other hand, Ivan Vozov's classic novel, Under the Yoke (1888), about the struggle for Bulgarian independence depicts centuries of rape and pillage against "the defenseless Bulgarians."[13] However, when history is reconstructed for a different reason, a more nuanced and accurate story can be constructed from available sources. Bulgaria's role, and that of the whole Balkan region, as a cultural bridge can be emphasized instead.

Notes

- ↑ Simeon Evstatiev, Round Table: The Contribution of Adult Education in the Context of Christian-Muslim Interaction and Mutual Understanding in Bulgaria, Sofia University "St. Kliment Ohridski." Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ B. Brentjes, On the Prototype of the Proto-Bulgarian Temples at Pliska, Preslav and Madara, East and West (Rome), New series. 21:3-4:213-216. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ Theophanes and Immanuel Bekker (ed.), Symeon of Bulgaria wins the Battle of Acheloos, 917, Theophanes Continuatus. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ↑ Theophanes (1977) 447-448.

- ↑ Theophanes (1977), 467.

- ↑ Theophanes (1977), 492.

- ↑ Barford (2001).

- ↑ Runciman (1930), 157.

- ↑ Fine (1991), 144–148.

- ↑ Сarl Gothard De Boor, Vita Euthymii (Berlin, DE: Reimer), 214.

- ↑ Theophanes (1977), 462—3, 480

- ↑ Lewis (1984), 135-6.

- ↑ Vazov (2005), 453.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barford, P.M. 2001. The Early Slavs. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801439773.

- Fine, Jr., John V.A. 1991. The Early Medieval Balkans. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472081493.

- Fine, Jr., John V.A. 1987. The Late Medieval Balkans. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Hupchick, Dennis P. 2001. The Balkans: from Constantinople to Communism. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave. ISBN 9780312217365.

- Lewis, Bernard. 1984. The Jews of Islam. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691008078.

- Ovcharov, Nikolaĭ. 2006. Medieval Bulgarian empire. Sofia, BG: Sofia Books. ISBN 9789545166372.

- Runciman, Steven. 1930. London, UK: G. Bell & Sons.

- Vazov, Ivan and Raymond Hansen ed. 2005. Under the Yoke. Sofia, BG: Pax Publishing. ISBN 9549403017.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.