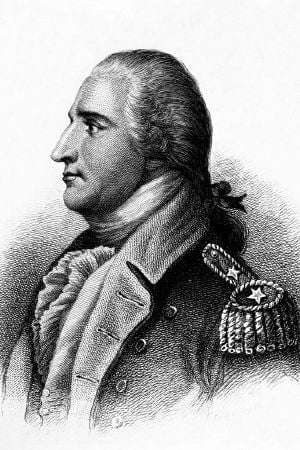

Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold (January 14, 1741 – June 14, 1801) was a famous American traitor, having been a general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He is best known for plotting to surrender the American fort at West Point, New York, to the British during the American Revolution.

Arnold earlier distinguished himself as a hero through acts of cunning and bravery at Fort Ticonderoga in 1775, and especially at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777.

However, Arnold strongly opposed the decision by the Continental Congress to form an alliance with France. Disaffected because of this and other grievances, suffering from mounting personal debt, and facing corruption charges filed by the Pennsylvania civil authorities, Arnold also faced pressure at home from his young second wife, Peggy Shippen, herself a British Loyalist.

In September 1780, he formulated his scheme, which, if successful, would have given British forces control of the Hudson River valley and split the colonies in half. The plot was thwarted, but Arnold managed to flee to British forces in New York, where he was rewarded with a commission as a Brigadier General in the British Army, along with a reward of £6,000.

Early life

Arnold was born the last of six children to Benedict Arnold III and Hannah Waterman King in Norwich, Connecticut, in 1741. Only Benedict and his sister Hannah survived to adulthood; the other four siblings succumbed to yellow fever while children. Through his maternal grandmother, Arnold was a descendant of John Lathrop, an ancestor of at least four Presidents of the United States.

The family was financially well off until Arnold's father made several bad business deals that plunged the family into debt. The father then turned to alcohol for solace. At 14, Benedict was forced to withdraw from school because the family could no longer afford the cost.

His father's alcohol abuse and ill health prevented him from training his son in the family mercantile business. However, his mother's family connections secured an apprenticeship for him with two of her cousins, the brothers Daniel and Joshua Lathrop, in their successful apothecary and general merchandise trade in Norwich.

At 15, Arnold enlisted in the Connecticut militia, marching to Albany and Lake George to oppose the French invasion from Canada at the Battle of Fort William Henry. The British suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of the French under the command of Louis Joseph Marquis de Montcalm. The Native American allies of the French, however, were outraged by the easy terms offered to the British and Colonial forces and slaughtered as many as 180 prisoners. The French failed to stop the massacre, and it was debated if they even seriously tried to prevent it. This event created an abiding hatred for the French in the young and impressionable Arnold, which influenced his actions later in life.

Arnold's mother, to whom he was very close, died in 1759. The youth took on the responsibility of supporting his ailing father and younger sister. His father's alcoholism worsened, and he was arrested on several occasions for public drunkenness and also was refused communion by his church. With his father's death in 1761, the 20 year old Arnold resolved to restore his family name to the elevated status it had once enjoyed.

Pre-revolutionary activities

In 1762, with the help of the Lathrops, Arnold established himself in business as a pharmacist and bookseller in New Haven, Connecticut. He was ambitious and aggressive, quickly expanding his business. In 1763, he repurchased the family homestead that his father had sold, re-selling it a year later for a substantial profit. In 1764, he formed a partnership with Adam Babcock, another young New Haven merchant. Using the profits from the sale of his homestead, they bought three trading ships and established a lucrative West Indies trade. During this time, he brought his sister Hannah to New Haven to manage his apothecary business in his absence. He traveled extensively throughout New England and from Quebec to the West Indies, often in command of one of his own ships.

The Stamp Act of 1765 severely curtailed mercantile trade in the colonies. Like many other merchants, Arnold conducted trade as if the Stamp Act did not exist—in effect becoming a smuggler in defiance of the act. On the night of January 31, 1767, Arnold took part in a demonstration denouncing the acts of the British Parliament and their oppressive colonial policy. Effigies of local crown officials were burned, and Arnold and members of his crew roughed up a man suspected of being a smuggling informant. Arnold was arrested and fined 50 shillings for disturbing the peace.

Arnold also fought a duel in Honduras with a British sea captain, who called Arnold a "Dammed Yankee, destitute of good manners or those of a gentleman." The captain was wounded and forced to apologize. Meanwhile, oppressive taxes levied by Parliament forced many New England merchants out of business, and Arnold himself came near to personal ruin, falling £15,000 in debt.

Arnold was in the West Indies when the Boston Massacre occurred on March 5, 1770, in which many colonists died. Arnold later wrote that he was "very much shocked" and wondered "good God; are the Americans all asleep and tamely giving up their liberties, or are they all turned philosophers, that they don't take immediate vengeance on such miscreants."

On February 22, 1767, Arnold married Margaret, daughter of Samuel Mansfield. They had three sons: Benedict, Richard, and Henry. However, she died on June 19, 1775, leaving Arnold a widower.

Revolutionary War

In March 1775, a group of 65 New Haven residents formed the Governor’s Second Company of Connecticut Guards. Arnold was chosen as their captain, and he organized training and exercises in preparation for war. On April 21, when news reached New Haven of the opening battles of the revolution at Lexington and Concord, a few Yale College student volunteers were admitted into the guard to boost their numbers, and they began a march to Massachusetts to join the revolution.

En route, Arnold met with Colonel Samuel Holden Parsons, a Connecticut legislator. They discussed the shortage of cannons and, knowing of the large number of cannons at Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain, agreed that an expedition should be sent to capture the fort. Parsons continued on to Hartford, where he raised funds to establish a force under the command of Captain Edward Mott. Mott was instructed to link up with Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys at Bennington, Vermont. Meanwhile, Arnold and his Connecticut militia continued on to Cambridge, where Arnold convinced the Massachusetts Committee of Safety to fund the expedition to take the fort. They appointed him a colonel in the Massachusetts militia and dispatched him, along with several captains under his command, to raise an army in Massachusetts. As his captains mustered troops, Arnold rode north to rendezvous with Allen and take command of the operation.

Battle of Ticonderoga

By early May, the army was assembled. The colonial forces surprised the outnumbered British garrison and on May 10, 1775, Fort Ticonderoga was taken without a battle after a dawn attack. Expeditions to Crown Point and Fort George were likewise successful, as was another foray to Fort St. Johns (now named Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu) Quebec. However, this fort had to be abandoned when British troops arrived from Montreal.

Throughout the campaign, Arnold and Allen disputed as to who was in overall command. Allen eventually withdrew his troops, leaving Arnold in sole command of the garrisons of the three forts. Soon, a Connecticut force of 1,000 men under Colonel Benjamin Himan arrived with orders placing him in command, with Arnold as his subordinate.

Despite a series of brilliant military successes, Arnold was caught in the middle of the political competitions of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and the Continental Congress, all vying for the honor of being responsible for capturing strategic Fort Ticonderoga. When Massachusetts, which originally supported Arnold, gave in to Connecticut, Arnold felt his efforts were unappreciated, indeed unrecognized. Meanwhile, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety was questioning Arnold's conduct and expenditures, even though Arnold had spent a thousand pounds of his own money on the cause. It was the last straw for Arnold; he resigned his commission as a Massachusetts militia colonel at Crown Point, New York.

On the way home to Connecticut, Arnold stopped at Albany where he briefed Major General Philip Schuyler, who had been appointed commander of the Northern Army. Arnold urged Schuyler to invade Canada. He also circulated a petition to stave off a Massachusetts Committee's inquiry into his alleged misdeeds. He collected 500 signatures from northern New Yorkers attesting to the protection he had provided them and their appreciation of his achievements. However, Arnold's visit was cut short when news reached him that his wife had died.

Quebec expedition

Major General Schuyler developed a plan to invade Canada overland from Fort St. Johns at the northern end of Lake Champlain, down the Richelieu River to Montreal. The objective was to deprive the Loyalists of an important base from which they could attack upper New York. General Richard Montgomery was given command of this force.

Arnold, now recommitted to the cause of the revolution, proposed that a second force, in concert with Schuyler’s, attack by traveling up the Kennebec River in Maine and descending the Chaudière River to Quebec City. With the capture of both Montreal and Quebec City, he believed the French-speaking colonists of Canada would join the revolution against the British. General George Washington and the Continental Congress approved this amendment and commissioned Arnold a colonel in the Continental Army to lead the Quebec City attack.

The force of 1,100 recruits embarked from Newburyport, Massachusetts, on September 19, 1775, arriving at Gardinerston, Maine, on September 22, where Arnold had made prior arrangements with Major Reuben Colburn to construct 200 shallow river boats. These were to be used to transport the troops up the Kennebec and Dead rivers, then down the Chaudiere to Quebec City. A lengthy portage was required over the Appalachian range between the upper Dead and Chaudiere rivers.

The British were aware of Arnold’s approach and destroyed most of the serviceable watercraft (boats, ships, gunboats, etc.) on the southern shore. Two warships, the frigate Lizard (26 guns) and the sloop-of-war Hunter (16 guns), kept up a constant patrol to prevent a river crossing. Even so, Arnold was able to procure sufficient watercraft and crossed to the Quebec City side on November 11. He then realized his force was not strong enough to capture the city and sent dispatches to Montgomery requesting reinforcements.

Meanwhile, Brigadier General Richard Montgomery marched north from Fort Ticonderoga with about 1,700 militiamen on September 16. He captured Montreal on November 13. Montgomery joined Arnold in early December, and with their combined force of about 1,325 soldiers, they attacked Quebec on December 31, 1775. The colonial forces suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of General Guy Carleton, governor of Canada and commander of the British forces. Montgomery was killed leading an assault and Arnold was wounded in the leg. Many others were killed or wounded, and hundreds were taken prisoner.

The remnants, reduced to some 350 volunteers and now under the command of Arnold, continued a siege of Quebec until the spring of 1776, when reinforcements under Brigadier General David Wooster arrived. Upon being relieved of command, Arnold retreated to Montreal with what remained of his forces.

Arnold received a promotion to Brigadier General after the Quebec invasion and was given the job of preventing a British invasion from the North. Around this time, he met and courted Betsy Deblois, the daughter of a well-known Loyalist of Boston. She was described at the time as the belle of Boston. Arnold tried to woo Deblois to marry him. However, she rebuffed him, even after the presentation of an engagement ring.

Eastern Department

Late in 1776, Arnold received orders to report to Major General Joseph Spencer, newly appointed commander of the Eastern Department of the Continental Army. On December 8, a sizable British force under Lt. Gen. Henry Clinton captured Newport, Rhode Island. Arnold arrived at Providence, Rhode Island, on January 12, 1777, to take up his duties in the defense of Rhode Island as Deputy Commander of the Eastern Department. The ranks of the Rhode Island force had been depleted to about 2,000 troops in order to support Washington’s assault on Trenton, New Jersey. Since Arnold was facing 15,000 redcoats, he was forced to go on the defensive.

On April 26, Arnold was on his way to Philadelphia to meet with the Continental Congress and stopped in New Haven to visit his family. A courier notified him a British force 2,000 strong under Major General William Tryon, the British Military Governor of New York, had landed at Norwalk, Connecticut. Tryon marched his force to Fairfield on Long Island Sound and inland to Danbury, a major supply depot for the Continental Army, destroying both towns by fire. He also torched the seaport of Norwalk as his forces retreated by sea.

Arnold hurriedly recruited about 100 volunteers locally and was joined by Major General Gold S. Silliman and Major General David Wooster of the Connecticut militia, who together had mustered a force of 500 volunteers from eastern Connecticut. Arnold and his fellow officers moved their small force near Danbury so they could intercept and harass the British retreat. By 11 a.m. on April 27, Wooster’s column had caught up with and engaged the British rear guard. Arnold moved his force to a farm outside Ridgefield, Connecticut, in an attempt to block the British retreat. During the skirmishes that followed, Wooster was killed, and Arnold injured his leg when his horse was shot and fell on him.

After the Danbury raid, Arnold continued his journey to Philadelphia, arriving on May 16. General Schuyler also was in Philadelphia at that time but soon left for his headquarters at Albany, New York. This left Arnold as the ranking officer in the Philadelphia region, so he assumed command of the forces there. However, the Continental Congress preferred Pennsylvania's newly promoted Major General Thomas Mifflin. Arnold, meanwhile, had earlier been passed over for promotion. Consequently, Arnold once again resigned his commission on July 11, 1777. Shortly afterwards, Washington urgently requested that Arnold be posted to the Northern Department because Fort Ticonderoga had fallen to the British. This demonstrated Washington's faith in Arnold as a military commander, and Congress complied with his request.

Saratoga campaign

The summer of 1777 marked a turning point in the war. The Saratoga campaign was a series of battles fought in upper New York near Albany that culminated in the American victory at the Battle of Saratoga and the capture of a large contingent of the British army led by Lieutenant General John Burgoyne on October 17, 1777. Arnold played a decisive role in several of these battles.

The Battle of Bemis Heights was the final battle of the Saratoga Campaign. Outnumbered, out of supplies, and cut off from retreat (largely by Arnold's doing), Burgoyne was forced to surrender on October 17, 1777. Arnold suffered another wound to the leg during the fray.

Historians agree that Arnold played an instrumental role in the outcome of the Saratoga campaign, showing courage, initiative, and military brilliance. But because of bad feelings between him and General Horatio Gates, Arnold received little or no credit. Even though Arnold was vital in winning the final battle of Saratoga, Gates vilified him for exceeding his authority and disobeying orders. Arnold, meanwhile, made no secret of his contempt for Gates' military tactics, which he considered too cautious and conventional.

Disability and disillusionment

By mid-October 1777, Arnold lay in an Albany hospital, convalescing from the wound he had received at Saratoga. His left leg was ruined, but Arnold would not allow it to be amputated. Several agonizing months of recovery left it two inches shorter than the right. He spent the winter of 1777-78 with the army at Valley Forge, recovering from the injury. After the evacuation of the British from Philadelphia in June 1778, George Washington appointed Arnold military commander of the city.

Also in June, Arnold learned of the newly formed Franco-American alliance. Arnold was strongly opposed to the alliance because of his earlier experiences in the French and Indian War. Ironically, it was the victory at Saratoga, in which Arnold had played a decisive part, that convinced France's King Louis XVI to agree to the alliance and aid the Americans in their war.

By then, Arnold was embittered and resentful toward Congress for not approving his wartime expenses and bypassing him for promotion. He threw himself into the social life of the city, hosting grand parties and falling deeply into debt. Arnold's extravagance drew him into shady financial schemes and into further disrepute with Congress, which investigated his accounts. On June 1, 1779, he was court-martialled for malfeasance. "Having become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet [such] ungrateful returns," he complained to Washington.

On March 26, 1779, Arnold met Peggy Shippen, the boisterous 18-year-old daughter of Judge Edward Shippen. She and Arnold wed quickly on April 8, 1779. Peggy had previously been courted by British Major John André during the British occupation of Philadelphia. The new Mrs. Arnold may have instigated correspondence between Arnold and André, who served as aide-de-camp to England's General Henry Clinton. She may also have been sending information to the British before she married Arnold. Evidence suggests that she confided to her friend Theodora Prevost, the widow of a British officer, that she had always hated the American cause and had actively worked to promote her husband's plan to switch allegiance. Other possible pro-British contacts in Philadelphia were loyalists Rev. Jonathan Odell and Joseph Stansbury.

Treason at West Point

In July 1780, Arnold sought and obtained command of the fort at West Point. He already had begun correspondence with British General Sir Henry Clinton in New York City through Major André and was closely involved with Beverley Robinson, a prominent Loyalist in command of a loyalist regiment. Arnold offered to hand the fort over to the British for £20,000 and a brigadier's commission.

West Point was valuable because of its strategic position, located above a sharp curve in the Hudson River. From the walls of West Point, it was possible for cannon fire to cover the river, preventing any ships from navigating it. Possession of West Point meant dividing the colonies, who depended on it for travel, commerce, and troop movement. Additionally, if Arnold had surrendered West Point to the British, then Washington would have had to retreat from his current, defensible position in New York, end his plans to unite with the French to attack Clinton in New York, and leave French troops exposed in Long Island. Clinton then could have defeated the French, perhaps changing the outcome of the entire war.

However, Arnold's treasonous plan was thwarted when André was captured with a pass signed by Arnold. André was also in possession of documents that disclosed the plot and incriminated Arnold. André was later convicted of being a spy and hanged. Arnold learned of André's capture and fled to the British. They made him a brigadier general, but only paid him some £6,000 because his plot had failed.

After Arnold fled to escape capture, his wife remained for a short time at West Point, long enough to convince George Washington and his staff that she had nothing to do with her husband's betrayal. From West Point she returned briefly to her parents' home in Philadelphia and then joined her husband in New York City.

Fighting for Britain

Arnold then became a British officer and saw important action in the American theater. In December, under orders from Clinton, Arnold led a force of 1,600 troops into Virginia and captured Richmond, cutting off the major artery of material to the southern colonial effort. It is said that Arnold asked an officer he had taken captive about what the Americans would do if they captured him, and the captain is said to have replied "Cut off your right leg, bury it with full military honors, and then hang the rest of you on a gibbet."

In the Southern Theater, Lord Cornwallis marched north to Yorktown, which he reached in May 1781. Arnold, meanwhile, had been sent north to capture the town of New London, Connecticut, in hopes it would divert Washington away from Cornwallis. While in Connecticut, Arnold's force captured Fort Griswold on September 8. In December, Arnold was recalled to England with various other officers as the Crown de-emphasized the American Theater over others in which victories were more likely.

After the war, Arnold pursued interests in the shipping trade in Canada, from 1787 to 1791, before moving permanently to London. He died in 1801, and was buried at St. Mary's Church, Battersea, in London. He is said to have died poor, in bad health, and essentially unknown.

His wife followed him to London, New Brunswick, and back to London again. She remained loyally at her husband's side in spite of financial disasters and the cool reception he received in Britain and New Brunswick. After his death, she used his estate to pay off his large debts.

Legacy

Today, Benedict Arnold's name is synonymous with treason, betrayal, and defection. Instead of remembering Arnold for his battlefield successes, both Americans and the world think of him as a traitor to the American nation in its most formative stages. In fact, the term, "Benedict Arnold" is synonymous with someone who cannot be trusted, a turncoat, or just being plain undependable. In the annals of American history, the sacred honor to which he aspired was unfortunately not to be Benedict Arnold's legacy.

Ironically, if Arnold had been killed at Saratoga instead of only being wounded there, he may have gone down in history as one of the greatest heroes of the American Revolutionary War. Indeed, a monument at Saratoga is dedicated to his memory. Called the "Boot Monument," it does not mention Arnold's name, but it is dedicated:

In memory of the most brilliant soldier of the Continental Army who was desperately wounded on this spot… 7th October, 1777, winning for his countrymen the decisive battle of the American Revolution and for himself the rank of Major General.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Nelson, James L. Benedict Arnold's Navy: The Ragtag Fleet that Lost the Battle of Lake Champlain but Won the American Revolution. McGraw-Hill, 2006. ISBN 0-07-146806-4.

- Randall, Willard Sterne. Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor. Dorset Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0760712726.

- Wallace, Audrey. Benedict Arnold: Misunderstood Hero? Burd Street Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1572493490.

- Wilson, Barry K. Benedict Arnold: A Traitor in Our Midst. McGill Queens Press, 2001 ISBN 077352150X.

External links

All links retrieved September 27, 2023.

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. www.biographi.ca.

- Biography at Historic Valley Forge. www.ushistory.org.

- Biographical profile of Arnold written in the 1880s. www.benedictarnold.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.