Antonio da Correggio

| Antonio da Correggio | |

Antonio Allegri da Correggio | |

| Birth name | Antonio Allegri |

| Born | August 1489 |

| Died | March 5 1534 (aged 44) Correggio, Duchy of Modena and Reggio |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Field | Fresco, painting |

| Movement | High Renaissance Mannerism |

| Famous works | Jupiter and Io Assumption of the Virgin |

Antonio Allegri da Correggio (August 1489 – March 5, 1534), usually known as just Correggio (/kəˈrɛdʒioʊ/, also UK: /kɒˈ-/, US: /-dʒoʊ/ Italian: [korˈreddʒo]), was an Italian Renaissance painter, the foremost painter of the Parma school of the High Italian Renaissance, who was responsible for some of the most vigorous and sensuous works of the sixteenth century. In his use of dynamic composition, illusionistic perspective and dramatic foreshortening, Correggio prefigured the Baroque art of the seventeenth century and the Rococo art of the eighteenth century.

His main works focused on religious themes, with many paintings of the Holy Family and various saints. His use of perspectival devices and lighting gives the viewer the feeling of being physically "pulled upward" into heaven. However, his later works delved into mythology, and were infused with a sense of seduction and eroticism. Such works might have been considered pornographic for their time, had Correggio not rendered his naked and semi-naked subjects with a subtlety and lightness of touch that elevated them to the realm of wondrous beauty.

Although Correggio died at the relatively young age of 44, and only produced around 40 works, he made a fundamental contribution to the development of painting. He is considered a master of color. His soft and delicate color contours counterbalanced his lines and effected a delicate balance between naturalism and poetics.

Life

Antonio Allegri was born in Correggio, a small town near Reggio Emilia. His date of birth is uncertain (around 1489). His father was a merchant. Otherwise little is known about Correggio's early life or training. It is, however, often assumed that he had his first artistic education from his father's brother, the painter Lorenzo Allegri.[1]

In 1503–1505, he was apprenticed to Francesco Bianchi Ferrara in Modena, where he became familiar with the classicism of artists like Lorenzo Costa and Francesco Francia, evidence of which can be found in his first works. After a trip to Mantua in 1506, he returned to Correggio, where he stayed until 1510.

In 1514, he worked on three tondos for the entrance of the church of Sant'Andrea in Mantua, and then returned to Correggio, where, as an independent and increasingly renowned artist, he signed a contract for the Madonna altarpiece in the local monastery of St. Francis (now in the Dresden Gemäldegalerie).

In 1519 he married Girolama Francesca di Braghetis, also of Correggio. The had a son, Pomponio Allegri, who was also a painter.[2] Both father and son occasionally referred to themselves using the Latinized form of the family name, Laeti.[3]

Returning to his home town in later years, Correggio died there suddenly on March 5, 1534. The following day he was buried in San Francesco in Correggio near his youthful masterpiece, the 'Madonna di San Francesco', housed today in Dresden. The precise location of his tomb is now unknown.

Works

In Parma

By 1516, Correggio was in Parma, where he spent most of his career. Here, he befriended Michelangelo Anselmi, a prominent Mannerist painter. From this period are the Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John, Christ Leaving His Mother, and the lost Madonna of Albinea.

Correggio's first major commission (February–September 1519) was the ceiling decoration of a private chamber of the mother-superior (abbess Giovanna Piacenza) of the convent of St. Paul in Parma, now known as Camera di San Paolo. Here he painted an arbor pierced by oculi opening to glimpses of playful cherubs. Below the oculi are lunettes with images of statues in feigned monochromic marble. The fireplace is frescoed with an image of Diana. The iconography of the scheme is complex, combining images of classical marbles with whimsical colorful bambini.

He then painted the illusionistic Vision of St. John on Patmos (1520–1521) for the dome of the church of San Giovanni Evangelista. The trompe l’oeil effect:

distinguishes between those who, for all they are reaching heavenward, nevertheless keep their feet firmly planted on the ground, and the central focus of the painting, the ascending figure of the Virgin floating away on a gleaming, fluid spiral composed of an endless swirl of angels and clouds.[4]

Three years later he decorated the dome of the Cathedral of Parma with a startling Assumption of the Virgin, crowded with layers of receding figures in Melozzo's perspective (sotto in su, from down to up).

These two works represented a highly novel illusionistic sotto in su treatment of dome decoration that would exert a profound influence upon future fresco artists, from Carlo Cignani in his fresco Assumption of the Virgin, in the cathedral church of Forlì, to Gaudenzio Ferrari in his frescoes for the cupola of Santa Maria dei Miracoli in Saronno, to Pordenone in his now-lost fresco from Treviso, and to the baroque elaborations of Lanfranco and Baciccio in Roman churches. The massing of spectators in a vortex, creating both narrative and decoration, the illusionistic obliteration of the architectural roof-plane, and the thrusting perspective toward divine infinity, were devices without precedent, and which depended on the extrapolation of the mechanics of perspective. The recession and movement implied by the figures presage the dynamism that would characterize Baroque painting.

Other masterpieces, commissioned by Parmesan noble Placido Del Bono for a chapel in the church of San Giovanni Evangelista in Parma, currently at the Galleria Nazionale of Parma, include The Lamentation and The Martyrdom of Four Saints. The Lamentation is among the earliest to use the swooning virgin motif. The fainting Virgin’s resemblance to Christ is notable, yet Correggio’s depiction of Christ himself also departs in various ways from tradition. It was not common, for instance, for him to be shown with both mouth and eyes partially open. Additionally, his hands are somewhat contorted with the fingers contracted. All of these elements are present in Bernini’s statue of Teresa, including a partially clenched right hand (something not found in swooning Virgin images).[5]

The Martyrdom of Four Saints depicts the martyrdom of Placidus and his sister Flavia and, behind them, that of two earlier Roman siblings, Eutychius and Victorinus, who appear to have been already beheaded. An angel flies above them and holds the palm of martyrdom. This painting resembles later Baroque compositions such as Bernini's Truth and Ercole Ferrata's Death of Saint Agnes, showing a gleeful saint entering martyrdom.

Mythological series

Correggio later turned from religious to mythological subject matter. He conceived a now-famous set of paintings depicting the Loves of Jupiter as described in Ovid's Metamorphoses. The voluptuous series was commissioned by Federico II Gonzaga of Mantua, probably to decorate his private Ovid Room in the Palazzo Te. However, they were given to the visiting Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and thus left Italy within years of their completion.

Leda and the Swan – acquired by Frederick the Great in 1753; now in Staatliche Museen of Berlin – is a tumult of incidents: in the center Leda straddles a swan, and on the right, a shy but satisfied maiden. This painting shows the influence of Michelangelo, whose treatment of the same subject matter, the original of which was lost and survives only in copies, demonstrated a similar sensual eroticism.

Danaë, now in Rome's Borghese Gallery, depicts the maiden as she is impregnated by a curtain of gilded divine rain. Correggio handles the scene with a delicacy and sensuality. Danaë's lower torso is semi-obscured by sheets, and she appears more demure and gleeful than Titian's 1545 version of the same topic. The picture once called Antiope and the Satyr is now correctly identified as Venus and Cupid with a Satyr.

Ganymede Abducted by the Eagle depicts the young man aloft in literal amorous flight. Some have interpreted the conjunction of man and eagle as an allegorical interpretation that prefigured Correggio's paintings of St John the Evangelist, referring to the flight of the intellect, liberated from earthly desires, toward the heaven of contemplation.[6] This painting and its partner, the masterpiece of Jupiter and Io, are in Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna.

Artistic Style

Correggio applied a certain sense of melancholy to his paintings, as seen in the finely finished fresco figures in the great tribune of the Duomo of Parma. The first to introduce the modern style into Lombardy, it was thought that Correggio’s work represented a challenge to the great artists of his time. However, since the artist never left Lombardy for Rome, he was unable to take advantage of experiencing firsthand the great works of antiquity or contemporary modern works, which could have raised his style to a more advanced level.[7] Thus, Correggio’s designs, although of good style, charm, and advanced skill were not the greatest of his age.

However, Correggio was a colorist without equal.[8] For example, in his paintings of a naked Leda and Venus, the coloring is so fine and the flesh tints so accomplished that the results appear to be actual flesh rather than paint. His work was filled with aesthetic sensitivities, from the remarkable beauty of the drapery to the subtle air of the figures with their life-like hair. No Lombard ever improved on Correggio’s landscapes, nor his lightly colored, polished hair. Indeed, in his treatment of hair, which is among the most difficult of subject matter, Correggio’s style presents a lesson in method from which future painters have greatly benefited. Biographer Giorgio Vasari remarked that in this and other works, Correggio:

painted hair in detail, not in the precise manner used by the masters before him, which was constrained, sharp, and dry, but soft and feathery, with each single hair visible, such was his facility in making them; and they seemed like gold and more beautiful than real hair, which is surpassed by that which he painted.[7]

Art historian Ellis K. Waterhouse noted that in his mythological works Correggio used the medium of oil painting to its fullest:

He was intrigued with the sensual beauty of paint texture and achieved his most remarkable effects in [this] series of mythological works [...] The sensuous character of the subject matter is enhanced by the quality of the paint, which seems to have been lightly breathed onto the canvas. These pictures carry the erotic to the limits it can go without becoming offensive or pornographic.[9]

Legacy

Correggio was remembered by his contemporaries as a shadowy, melancholic, and introverted character. An enigmatic and eclectic artist, he appears to have emerged from no major apprenticeship. In addition to the influence of Costa, there are echoes of Mantegna's style in his work, and a response to Leonardo da Vinci, as well.

His greatest artistic contribution may have been his remarkable adoption of the modern style.[8] Correggio had little immediate influence in terms of apprenticed successors, but his works are now considered to have been revolutionary and influential on subsequent artists. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, his works were often noted in the diaries of foreign visitors to Italy, which led to a reevaluation of his art during the period of Romanticism. The flight of the Madonna in the vault of the cupola of the Cathedral of Parma inspired many scenographical decorations in lay and religious palaces during those centuries.

Correggio's illusionistic experiments, in which imaginary spaces replace the natural reality, seem to prefigure many elements of Mannerist, Baroque, and Rococo stylistic approaches. For example, Ganymede Abducted by the Eagle, one of the four mythological paintings commissioned by Federico II Gonzaga, is a proto-Baroque work due to its depiction of movement, drama, and diagonal compositional arrangement.

Correggio had no direct disciples outside of Parma, where he was influential on the work of Giovanni Maria Francesco Rondani, Parmigianino, Bernardo Gatti, Francesco Madonnina, and Giorgio Gandini del Grano.

Selected works

- Judith and the Servant (c. 1510)—Oil on canvas,Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg

- Holy Family with Saints Elizabeth and John the Baptist (c. 1510)—Oil on panel-Pavia Civic Museums, Pavia

- The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine (1510–1515)—National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

- Madonna (1512–1514)—Oil on canvas, Castello Sforzesco, Milan

- Madonna and Child with St Francis (1514)—Oil on wood, 299 × 245 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

- Madonna and Child (unknown, early 1500s)—Oil on canvas, National Gallery for Foreign Art, Sofia

- Madonna of Albinea (1514, lost)

- Madonna and Child with the infant Saint John the Baptist (1514–1515)—Oil on wood panel, 45 × 35.5 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

- Madonna and Child with the Infant John the Baptist (c. 1515)—Oil on panel, 64.2 × 50.2 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

- The Holy Family with Saint Jerome (1515)–East Closet of Hampton Court Palace as part of the Royal Collection

- Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John (1515 - 1517)—Oil on canvas, 48 × 37 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid[10]

- Adoration of the Magi (c. 1515–1518)–Oil on canvas, 84 × 108 cm, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

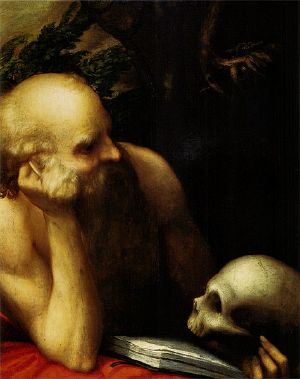

- Saint Jerome (c. 1515–1518)–Oil on Wood 64 x 51 cm, Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid[11]

- Madonna and Child with the Infant John the Baptist (1518)–Oil on panel, 48 x 37 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Portrait of a Gentlewoman (1517–1519)—Oil on canvas, 103 × 87.5 cm, Hermitage, St. Petersburg

- Frescoes for Camera di San Paolo (1519)—Monastery of San Paolo, Parma

- The Rest on the Flight to Egypt with Saint Francis (c. 1520)—Oil on canvas, 123.5 × 106.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

- Portrait of a man (c. 1520)–Oil on canvas, 55 x 40 cm, Museo Nacional Thyssen Bornemisza, Madrid[12].

- Death of St. John (1520–1524)—Fresco, San Giovanni Evangelista, Parma

- Madonna della Scala (c. 1523)—Fresco, 196 × 141.8 cm, Galleria Nazionale, Parma

- Martyrdom of Four Saints (c. 1524)—Oil on canvas, 160 × 185 cm, Galleria Nazionale, Parma

- Virgin and Child with an Angel (Madonna del Latte) (c. 1524)—Oil on wood, 68 × 56 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

- Deposition from the Cross (1525)—Oil on canvas, 158.5 × 184.3 cm, Galleria Nazionale, Parma

- Noli me Tangere (c. 1525)—Oil on canvas, 130 × 103 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid[13]

- Ecce Homo (1525–1530)—Oil on canvas, National Gallery, London

- Madonna della Scodella (1525–1530)—Oil on canvas, 216 × 137 cm, Galleria Nazionale, Parma

- Adoration of the Child (c. 1526)—Oil on canvas, 81 × 67 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence

- Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine (mid-1520s)—Wood, 105 × 102 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Assumption of the Virgin (1526–1530)—Fresco, 1093 × 1195 cm, Cathedral of Parma

- Madonna of St. Jerome (1527–1528)—Oil on canvas, 205.7 × 141 cm, Galleria Nazionale, Parma

- Venus with Mercury and Cupid ('The School of Love') (c. 1528)—Oil on canvas, 155 × 91 cm, National Gallery, London

- Venus and Cupid with a Satyr (c. 1528)—Oil on canvas, 188 × 125 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Nativity (Adoration of the Shepherds, or Holy Night) (1528–1530)—Oil on canvas, 256.5 × 188 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

- Madonna and Child with Saint George (1530–1532)—Oil on canvas, 285 × 190 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

- Danaë (c. 1531)—Tempera on panel, 161 × 193 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Ganymede Abducted by the Eagle (1531–32)—Oil on canvas, 163.5 × 70.5 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Jupiter and Io (1531–32)—Oil on canvas, 164 × 71 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Leda with the Swan (1531–32)—Oil on canvas, 152 × 191 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

- Allegory of Virtue (c. 1531)—Oil on canvas, 149 × 88 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Allegory of Vice (c. 1531)—Oil on canvas, 149 × 88 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

Gallery

Notes

- ↑ Conrado Ricci, Antonio Allegri da Correggio: His Life, his Friends, and his Time (Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2006, ISBN 978-1428611597).

- ↑ Vincent Finnan, Antonio Allegri Correggio: The Renaissance Artist of Parma Italian Renaissance Art. Retrieved April 6, 2024.

- ↑ Henry Fuseli and John Knowles, The Life and Writings of Henry Fuseli Volume 3 (Palala Press, 2016 (original 1831), ISBN 978-1356058907).

- ↑ Paul Elliman, Voices Falling Through the Air Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 10 (2012):66-71. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ↑ Andrea Bolland, Alienata da’ sensi: reframing Bernini’s S. Teresa Open Arts Journal 4 (Winter 2014–15):133-157. Retrieved April 7, 2024.

- ↑ Emil Krén and Daniel Marx, Ganymede by Correggio Web Gallery of Art. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Giogio Vasari, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (Modern Library, 2006 (original 1896), ISBN 978-0375760365).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Julius Meyer, Mrs Charles Heaton (trans.), Antonio Allegri Da Correggio (HardPress Limited, 2021 (original 1876), ISBN 978-0371312513).

- ↑ Antonio da Correggio The Art Story. Retrieved April 8, 2024.

- ↑ The Virgin and Child with Saint John Museo Nacional del Prado. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ↑ San Jerónimo Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ↑ Portrait of a Man Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- ↑ Noli me tangere Museo Nacional del Prado. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Coxe, William. Sketches of the Lives of Correggio and Parmegiano. Wentworth Press, 2019, (original 1823). ISBN 978-0469693708

- Ekserdjian, David. Correggio. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0300072990

- Freedburg, S.J. Painting in Italy, 1500-1600. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0300055863

- Fuseli, Henry, and John Knowles. The Life and Writings of Henry Fuseli Volume 3. Palala Press, 2016 (original 1831), ISBN 978-1356058907).

- Gould, Cecil Hilton Monk. The Paintings of Correggio. London: Faber, 1976. ISBN 978-0571105809

- Hartt, Frederick, and David G. Wilkins. History of Italian Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prenctice Hall, 2006. ISBN 978-0131882478

- Meyer, Julius, Mrs Charles Heaton (trans.). Antonio Allegri Da Correggio. HardPress Limited, 2021 (original 1876). ISBN 978-0371312513

- Ricci, Corrado. Antonio Allegri da Correggio: His Life, His Friends, and His Wife. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2006. ISBN 978-1428611597

- Vasari, Giorgio, Gaston du C. de Vere (trans.). The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Modern Library, 2006 (original 1896). ISBN 978-0375760365

External links

All links retrieved April 3, 2024.

- Works by Correggio Corregio (Antonio Allegri)

- Antonio Allegri Da Correggio by Dr. Julius Meyer

- Antonio da Correggio The Art Story

- Antonio da Correggio Art Institute Chicago

- Correggio – Artwork & Bio of the Italian Painter Artchive

- Antonio Allegri Correggio Italian Renaissance Art

- Museo Il Correggio

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.