Anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human characteristics and qualities to non-human beings, objects, natural, or supernatural phenomena. God, animals, the forces of nature, and unseen or unknown authors of chance are frequent subjects of anthropomorphosis. The term comes from two Greek words, άνθρωπος (anthrōpos), meaning "human," and μορφή (morphē), meaning "shape" or "form." The suffix "-ism" originates from the morpheme "-isma" in the Greek language.

Anthropomorphism has significantly shaped religious thought. Polytheistic and monotheistic faiths have apprehended the nature of divine being(s) in terms of humans characteristics. In early polytheistic religions human qualities and emotions—including passions, lusts and petty willfulness—were readily identified with the divinities. Early Hebrew monotheism scriptural representations of God are replete with human attributes, however, they lack comparable attributions of human vices.

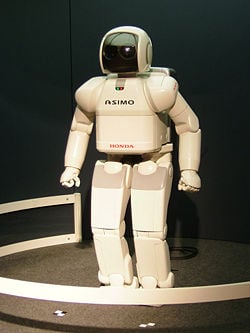

Anthropomorphism is frequently used as a device in art, literature, and film to convey the author’s message through a symbolic animal or object with human qualities. In technology and science, the behavior of machines and computers is sometimes described in terms of human behavior. The modern science of robotics, which develops machines to carry out automated tasks or enhance human performance, employs anthropomorphism to engage human beings intellectually and emotionally with machines or computers. Computer science studies and attempts to emulate the processes of the human brain in technology.

Anthropomorphism in religion

Since most religious beliefs are homocentric, concerned with questions such as the purpose of humanity’s existence, the origin of human beings, and humanity’s place in the universe, many belief systems assign human attributes to the divine. From the perspective of believers of a religion where the deity or deities have human characteristics, it may be more accurate to describe the phenomenon as “theomorphism,” or the giving of divine qualities to humans, instead of anthropomorphism, the giving of human qualities to the divine. In most belief systems, the deity or deities existed before humans, and therefore humans were created in the form of the divine. This resemblance implies some kind of kinship between human beings and God, especially between humanity’s moral being and God.

For philosophically-minded theists and adherents to theological systems such as Vedanta, the essence of God is impersonal Being, the "ground of being." Omnipotent, omnipresent, and uncaused, God is totally incommensurate with creation. From that perspective, anthropomorphic conceptions of deity are indeed projections of human qualities on the ineffable. Anthropomorphism, then, is taken to be fundamentally flawed, and only manifests popular ignorance.

Mythologies

Ancient mythologies frequently represented the divine as a god or gods with human forms and qualities. These gods resemble human beings not only in appearance and personality; they exhibited many human behaviors which were used to explain natural phenomena, creation, and historical events. The gods fell in love, married, had children, fought battles, wielded weapons, and rode horses and chariots. They feasted on special foods, and sometimes required sacrifices of food, beverage, and sacred objects to be made by human beings. Some anthropomorphic gods represented specific human concepts, such as love, war, fertility, beauty, or the seasons. Anthropomorphic gods exhibited human qualities such as beauty, wisdom, and power, and sometimes human weaknesses such as greed, hatred, jealousy, and uncontrollable anger. Greek gods such as Zeus and Apollo were often depicted in human form exhibiting both commendable and despicable human traits. The avatars of the Hindu god Vishnu possessed human forms and qualities. Norse myths spoke of twelve great gods and twenty-four goddesses who lived in a region above the earth called Avgard. The Shinto faith in Japan taught that all Japanese people were descended from a female ancestor called Amaterasu.

Anthropomorphic gods are depicted in ancient art found at archaeological sites all over the world. Greek and Roman statuary, Mayan and Aztec friezes, pre-Colombian and Inca pottery and jewelry, Hindu temples and carvings, Egyptian frescoes and monuments, and African masks and fertility statues continue to inspire and awe contemporary observers with their beauty and spirituality.

Anthropomorphism in the Bible

The first book of the Hebrew Bible depicts God with qualities and attributes similar to those of human beings. The key text is Genesis 1:27, listed below in the original Hebrew, and in English translation:

וַיִּבְרָא אֱלֹהִים אֶת-הָאָדָם בְּצַלְמוֹ, בְּצֶלֶם אֱלֹהִים בָּרָא אֹתוֹ: זָכָר וּנְקֵבָה, בָּרָא אֹתָם.

God created man around His own image, in the image of God He created him; male or female He created them (Genesis 1:27).

The Hebrew Bible frequently portrays God as a master, lord, or father, at times jealous and angry, at other times responding to the supplications of his people with mercy and compassion. In the New Testament, Jesus emphasizes God’s fatherly love and uses parables such as the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32) and The Lost Sheep (Matthew 18:12) to demonstrate the way in which God loves all of humanity. Jesus never taught that God had a physical body resembling a human being, but that God resembled humanity in heart and love.

Hinduism

The ten avatars of the Hindu supreme God Vishnu possess both human and divine forms and qualities, although their divinity varies in degree. In Vaishnavism, a monotheistic faith, Vishnu is omniscient and benevolent, unlike gods of the Greek and Roman religions.

Condemnation of anthropomorphism

Numerous religions and philosophies have condemned anthropomorphism for various reasons. Some Ancient Greek philosophers did not condone, and were explicitly hostile to, their people's mythology. Many of these philosophers developed monotheistic views. Plato's (427–347 B.C.E.) Demiurge (craftsman) in the Timaeus and Aristotle's (384 - 322 B.C.E.) prime mover in his Physics are examples. The Greek philosopher Xenophanes (570 - 480 B.C.E.) said that "the greatest God" resembles man "neither in form nor in mind." (Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies V xiv 109.1-3). The similarity of these philosophers' monotheistic concepts of God to that of the Bible's concept was acknowledged by early Christian fathers, especially Origen, and facilitated the incorporation of much pre-Christian Greek philosophy into the Medieval Christian world view by the Scholastics, notably Thomas Aquinas.

Philo Judaeus (20 B.C.E.–50 C.E.) also followed the early Greek philosophers and taught that God could not be named. Arabian philosophers denied that the essence of God had any attributes, and attempted to define God by “what He was not.” Jewish thinkers such as Maimonides (1135-1204) adopted this concept from Islamic Aristotelanism. Spinoza (1632-1677) denied any commonality between God and humans; he was followed later by J.G. Fichte and Matthew Arnold.

Throughout the history of Christianity sects called anthropomorphites, including a sect in Egypt in the fourth century, and a group in the Roman Catholic Church in the tenth century, were considered heretical for taking everything written and spoken of God in the Bible in a literal sense. This included attributing to God a human form, human parts, and human passions.

In rhetoric

In classical rhetoric, personification is a figure of speech (trope) that employs the deliberate use of anthropomorphism, often to make an emotional appeal. In rhetorical theory, a distinction is often drawn between personification (anthropomorphism of inanimate, but real, objects) and tropes such as apostrophe, in which absent people or abstract concepts are addressed.

An example of rhetorical personification:

- A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

- Against the earth's sweet-flowing breast. Joyce Kilmer, Trees

An example of rhetorical apostrophe:

- O eloquent, just, and mighty Death! Sir Walter Raleigh, History of the World

In literature, art, and song

Anthropomorphism is a well established device in literature, notably in books for children, such as those by C.S. Lewis, Rudyard Kipling, Beatrix Potter, Roald Dahl, and Lewis Carroll. Rev. W. Awdry's Railway Series depicts steam locomotives with human-like faces and personalities. Giving human voices and personalities to animals or objects can win sympathy and convey a moral or philosophical message in a way that ordinary human characters can not. Folk tales like the “Brer Rabbit” stories of the southern United States and Aesop’s Fables help to teach children lessons about ethics and human relationships. The Indian books Panchatantra (The Five Principles) and The Jataka Tales employ anthropomorphized animals to illustrate various principles of life. Anthropomorphic animals are also used to make comments on human society from an outsider’s point of view. George Orwell's Animal Farm is a contemporary example of the use of animals in a didactic fable.

The human characteristics commonly ascribed to animals in popular culture are usually related to their perceived personality or disposition (for example, owls are usually represented as wise); their appearance (penguins are usually portrayed as plump aristocrats, because their plumage resembles a black tuxedo); or a combination of both (raccoons are commonly portrayed as bandits, both because the characteristic black stripe over their eyes resembles the mask of a bandit, and because they roam at night and sometimes steal food). Such personification usually stems from ancient myths or folk tales, but some symbolism is modern. For example, foxes have been traditionally portrayed as wily and cunning, but penguins were not widely known of before the twentieth century, so all anthropomorphic behavior associated with them is more modern.

Modern anthropomorphism often projects human characteristics on entities other than animals, such as the red blood cells in the film Osmosis Jones and the automobiles in the 2006 Disney/Pixar movie Cars.

Many of the most famous children's television characters are anthropomorphized comical animals, such as Mickey Mouse, Kermit the Frog, Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Scrooge McDuck. Similarly adult-oriented television series such as Family Guy and Mr. Ed also make use of anthropomorphized characters. Anthropomorphic monsters and fantastical beings are frequently portrayed in science fiction and fantasy as having only superficial details (such as ears or skin color) that differ from normal humans.

Anthropomorphic animal characters are often used in songs and poems for children to add an element of novelty and delight.

Anthropomorphism and technology

It is a common tendency for people to think of inanimate objects as having human-like characteristics. Common examples of this tendency include naming one's car, singing to plants, or begging a machine to work. In 1953 the United States Government began assigning hurricanes female names. A few years later they added male names. Historically, storms were often named after saints.

This tendency has taken on a new significance with advances in artificial intelligence which allow computers to recognize and respond to spoken language. In business, computers have taken over functions formerly performed by humans, such as transferring telephone calls and answering simple customer service inquiries. This can only succeed if the computer is able to resemble a human being enough to trigger a normal response from the customer and inspire them to cooperate, by using appropriate language and reproducing sympathetic human voice tones.

Sophisticated programs now allow computers to mimic specific human thought processes. These computers exhibit human-like behavior in specialized circumstances, such as learning from mistakes or anticipating certain input, and playing chess and other games which require human-like intelligence. A new field of science has developed to study the processes of the human brain and attempt to reproduce them with technology.

The field of robotics recognizes that robots which interact with humans must display human characteristics such as emotion and response in order to be accepted by their users. Designers of robots include human-like posture and movement, lights, and facial features to satisfy this need. The popularity of modern robotic toys shows that people can feel affection for machines which display human characteristics.

Technical use

Anthropomorphic terminology is common in technical and scientific fields as a time-saving metaphorical device. Complex technology, such as machinery and computers, can exhibit complicated behavior that is difficult to describe in purely inanimate terms. Technicians, computer programmers and machine operators may use human actions and even emotions to describe the behavior of a machine or computer. A chemist might casually explain an ionic bond between sodium and chlorine by asserting that the sodium atom "wants" to merge with the chlorine atom, even though atoms are incapable of having a preference. As a financial market rises and falls, it might be described as "fickle."

In logical reasoning

Using anthropomorphized caricatures or projecting human qualities on conceptual entities or inanimate objects in reasoning is known as committing a pathetic fallacy (not a negative term).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barber, Theodore Xenophon. 1994. The Human Nature of Birds: A Scientific Discovery With Startling Implications. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0140234947.

- Crist, Eileen. 2000. Images of Animals: Anthropomorphism and Animal Mind (Animals, Culture, and Society Series). Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1566397889.

- Daston, Lorraine and Gregg Mitman (eds.). 2006. Thinking With Animals: New Perspectives on Anthropomorphism. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231130394.

- Kennedy, J. S. 2003. The New Anthropomorphism. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521422673.

- Mitchell, Robert W., Nicholas S. Thompson, H. Lyn Miles, (eds.). 1997. Anthropomorphism, Anecdotes, and Animals. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791431269.

- Shipley, Orby (ed.). 1872. A Glossary of Ecclesiastical Terms.

- This article incorporates content from the 1728 Cyclopaedia, a publication in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved July 31, 2023.

- Anthropomorphism, Anthropomorphites Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Anthropomorphism The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, & Spaceflight.

General philosophy sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.