Achomawi

| Achomawi | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

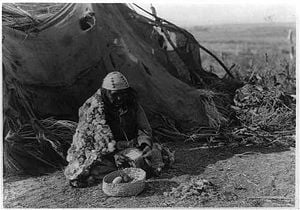

| Achomawi woman (circa 1920) | |||

| Total population | |||

| Regions with significant populations | |||

| |||

| Languages | |||

| Palaihnihan | |||

| Religions | |||

The Achomawi (also Achumawi, Ajumawi, and Ahjumawi) were one of several bands known as the "Pit River" tribe of Native Americans who lived in northern California. They lived in the Fall River valley, Tule Lake, and Pit River area near Montgomery Creek in Shasta County to Goose Lake on the Oregon state line. They were closely related to the Atsugewi; both speaking Palaihnihan languages. Their name, "Achomawi," translates to "River people."

The Achomawi lived a relatively peaceful albeit difficult life prior to European contact. They traded with neighboring tribes, bartering so that each group had sufficient resources to meet their needs, and were able to manage their resources, such as fish, effectively through their understanding and desire to live in harmony with nature. When Europeans first arrived, they were able to relate to them through trade. However, the California Gold Rush of 1849 disturbed their traditional lifestyle, bringing mining and other activities that took their lands and led to conflicts as well as diseases such as smallpox that ravaged their population. Finally, reservations were established and the surviving Achomawi were forced to relocate there.

Today, Achomawi live close to their ancestral homelands. They have combined features of contemporary life, such as operating a casino, with their traditional knowledge and ways of living in harmony with nature, operating environmental programs that benefit not only their local community but the larger population as a whole.

Territory

The Pit River or Pitt River is a major river watershed draining Northeastern California into the State's Central Valley. The Pit, the Klamath, and the Columbia are the only three rivers in the U.S. that cross the Cascade Range.

Historically, Achomawi territory was in the Pit River drainage area (with the exception of Hat Creek and Dixie Valley, which were Atsugewi).

The river is so named because of the pits the Achumawi dug to trap game that came to drink there. The Pit River drains a sparsely-populated volcanic highlands area, passing through the south end of the Cascade Range in a spectacular canyon northeast of Redding.

This region, from Mount Shasta and Lassen Peak to the Warner Range, has a tremendous ecological diversity yielding a huge variety of foods, medicines, and raw materials. The total area was probably one hundred and seventy-five miles in length as the river flows, and began near Round mountain in the south to Goose Lake area to the north (Curtis 1924).

Strictly speaking, Achomawi is the name of only that part of the group living in the basin of the Fall River (Kroeber 1925). Other groups in the Pit River area included:

- Madeshi, lowest on the river

- Ilmawi, along the river's south side

- Chumawi, in Round Valley

- Atuami, in Big Valley

- Hantiwi, in lower Hot Springs Valley

- Astakiwi, upper Hot Springs Valley

- Hamawi, on the south fork of the Pit River

Population

Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. Alfred L. Kroeber (1925) estimated the combined 1770 population of the Achomawi and Atsugewi as 3,000. A more detailed analysis by Fred B. Kniffen (1928) arrived at the same figure. T. R. Garth (1978) estimated the Atsugewi population at a maximum of 850, which would leave at least 2,150 for the Achomawi.

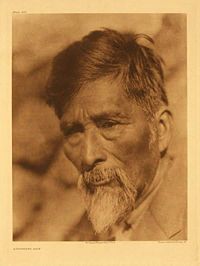

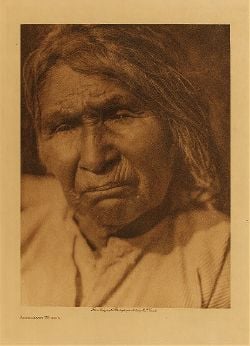

Kroeber estimated the combined population of the Achomawi and Astugewi in 1910 as 1,100. Edward S. Curtis, a photographer and author in the 1920s, gave a 1910 population of Achomawi at 984.

History

The Achomawi had as their neighbors the Modoc, Klamath, and the Atsugewi to the north, the Shasta to the northwest, the Wintun westward, the Yana on the southeast, and the Maidu to the south, and the Paiute to the east. Prior to European contact, the Achomawi had intermittent hostilities with these neighbors, although the Wintun and Maidu were too peaceful to engage in real physical conflict (Curtis 1924). They did, however, suffer as victims of slave raids carried out by the Klamath and Modoc tribes who rode horses (Waldman 2006). The Achomawi who did not have horses could offer little resistance and were captured and sold at the Dalles intertribal slave market on the Columbia River in Oregon (Garth 1978).

The Achomawi engaged in barter trade with their neighbors. They traded basketry caps, salmon flour, steatite (soapstone), acorns, salmon, dentalia, tule baskets, and rabbit-skin blankets to the Atsugewi in return for seed foods, furs, hides, and meat. They supplied the Maidu with obsidian, bows and arrows, dear skins, sugarpine nuts, and shell beads in return for clam shell disc beads, salt, and digger pine nuts. They obtained salmon flour, clam shell disc beads, and dentalia from the Wintun in exchange for salt, furs, and bows. They gave the Yana obsidian and received buckeye fire drills, deer hides, dentalia, and salt (Davis 1974).

European fur-trappers and traders arrived in the area in the first half of the nineteenth century. However, it was not until the California Gold Rush of 1849 that they disturbed the traditional lifestyle of the Achomawi. The Gold rush era brought mining and other activities that took their lands, and also brought diseases such as smallpox that ravaged their population. Conflicts, such as the 1855 Rogue River War involving tribes to their north in Oregon brought a military presence to the area. Finally, reservations were established and the surviving Achomawi were forced to relocate there.

Language

The Achumawi language (also Achomawi or Pit River language) is the native language spoken by the Pit River people of present-day California. The term Achumawi is an anglicization of the name of the Fall River band, ajúmmááwí, from ajúmmá "river." Originally there were nine bands, with dialect differences among them but primarily between upriver and downriver dialects, demarcated by the Big Valley mountains east of the Fall River valley. Together, Achumawi and Atsugewi are said to comprise the Palaihnihan language family.

Today, the Achumawi language is severely endangered. Out of an estimated 1500 Achumawi people remaining in northeastern California, perhaps ten spoke the language as of 1991, with only eight in 2000. However, out of these eight, four had a limited English proficiency.

Culture

Like other Northern Californians, the Achomawi lived by hunting and gathering and fishing. They were intimately familiar with their environment and were able to take full advantage of the available resources: "No feature of the landscape of noticeable size seems to have been without a name" (Kniffen 1928).

Fishing

Fish were essential to the traditional Achomawi diet. They were truly river people:

The real Achomawi were River Indians; they stayed around the river, fished; every man had a canoe and belonged to the river. They went out (hunting) for a little while, then returned to the river (Voeglin 1946).

To catch fish they built fish traps near the shore. These were composed of lava stone walls, with an outer wall and inner walls that concentrated the issuing spring water to attract the sucker fish (Catostomidae) and trout. The openings were then closed using a keystone, canoe prow, or log. The inner walls trapped the fish in the shallow gravel area directly in front of the spring's mouth, where they could be taken by spear or basket. The harvest was done in the evening using torches for light to show the fish, which could number in the hundreds (Foster 2008). The shallow gravel enclosure was also the spawning grounds for the sucker fish.

The Achomawi were careful to ensure that when an adequate supply of fish had been taken, the trap was opened so that fish were able to resume their spawn. In this way they both harvested and propagated these fish; an example of active resource management (Foster 2008).

Nets were another method employed to snare trout, pike, and sucker fish. The Achomawi made five different types, three of which were bag-shaped dipnets, the others being a seine and a Gillnet. The smallest dipnet, the lipake, consisted of a round bag with an oval hoop sewn at the mouth that was used to scoop up the sucker fish while diving underwater (Curtis 1924).

The fish were sun-dried or smoked on wooden frames for later consumption or trade with other groups.

Hunting

Hunting techniques differed from other California Native Americans. A deep pit would be dug along a deer trail. They then covered it with brush, restoring the trail by adding deer tracks using a hoof, and removing all dirt and human evidence. The pits were most numerous near the river because the deer came down to drink there. The Pit River is so named for these trapping pits (Powers 1976).

However, the settlers' cattle would also fall in these pits, so much so that the settlers convinced the people to stop this practice.

Gathering

Acorns, pine nuts, seeds of wild oats and other grasses, manzanita berries, and other berries were prepared for consumption, winter storage, and for trade. The plant commonly called camas (Camassia Quamash) was (and still is) an important food source of many Native American groups and was widely traded. Used as a sweetener and food enhancer, the bulbs were traditionally pit-cooked for more than a day (Stevens and Darris 2006).

Basketry

Achomawi basketry was of the twined type. Cooking vessels had broad openings, slightly rounded bottom, and sides with willow rods for upright structure. Other types of baskets were the burdenbasket, cradle, serving-tray, and the open-mesh beater basket for harvesting seeds. Achomawi made use of bear grass (a grasslike perennial closely related to lilies, known by several common names, including elk grass, squaw grass, soap grass, quip-quip, and Indian basket grass (Xerophyllum tenax, a plant with long and very durable grass-like leaves) for an overlay of wheat-colored strands with black stems of maidenhair fern (Adiantum) for background color (Curtis 1024).

Traditional beliefs

Achomawi traditional narratives include myths, legends, and oral histories. They did not have a formalized religion with ceremonies, rituals, and priests, or formal creation myths. Rather, they told stories of the old times, before human beings lived upon the earth, often during the long winter months gathered around the fire in their winter houses to keep warm. Although there was no "organized religion," for the Achomawi "life was permeated through and through with religion" (Angulo 1974).

Singing was an important part of daily life, with songs often acquired through dreams, and thought to be associated with certain powers. An Achomawi described this view:

All things have life in them. Trees have life, rocks have life, mountains, water, all these are full of life. ... When I came here to visit you, I took care to speak to everything around here ... I sent my smoke to everything. That was to make friends with all things. ... The stones talk to each other just as we do, and the trees too, the mountains talk to each other. You can hear them sometimes if you pay close attention, especially at night, outside. ... I do not forget them. I take care of them, and they take care of me (Angulo 1975).

Shamans sang songs to connect to the mysterious forces of life that dwell in everything (Angulo 1974). Shamans acquired power through tamakomi, calling on it by singing and smoking, and then asking it to cure sickness. The shaman was called to the position through visions and then apprenticed under elder shamans. Shamans also observed special dietary taboos against eating fresh fish and meat in order to ensure heavy salmon runs and a good catch (Powers 1976).

Certain animals were believed to have special powers. Thus, hummingbird feathers and beavers were thought to bring luck in gambling. Reptiles were viewed as having strong supernatural power, as was the coyote (Olmstead and Stewart 1978).

Contemporary Achomawi

Contemporary Achomawi, together with other bands such as the Astugewi, are known collectively as the Pit River Indians or "Tribe." On August, 1964, a Constitution was formally adopted by this Pit River Tribe. The Preamble states:

… for the purpose of securing our Rights and Powers inherent in our Sovereign status as reinforced by the laws of the United States, developing and protecting Pit River (Ajumawi-Atsugewi) ancestral lands and all other resources, preserving peace and order in our community, promoting the general welfare of our people and our descendants, protecting the rights of the Tribe and of our members, and preserving our land base, culture and identity (Pit River Tribe 1964).

The Tribe operates a day care center, health care services, an environmental program, and Pit River Casino, a Class III gaming facility located on 79 acres in Burney, California. There is a Housing Authority that through government grants has developed community housing projects, such as housing for low income families and elders.

Today there are around 1,800 tribal members living on the Alturas, Big Bend, Big Valley, Likely, Lookout, Montgomery Creek, Redding, Roaring Creek, and Susanville rancherias, as well as on the Pit River, Round Valley, and X-L Ranch reservations.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Angulo, Jamie de. 1974. Achomawi sketches. The Journal of California Anthropology 1(1): 80-85.

- Angulo, Jamie de. 1975. The Achomaw life-force. The Journal of California Anthropology 2(1): 60-63.

- Curtis, Edward S. [1924] 2007. The Achomawi. The North American Indian, Vol. 13. Northwestern University Digital Library Collections. Retrieved November 10, 2008. Classic Books. ISBN 978-0742698130.

- Davis, James Thomas. 1974. Trade Routes and Economic Exchange among the Indians of California. Ballena Press.

- Dixon, Roland B. 1908. Achomawi and Atsugewi Tales. Journal of American Folk-Lore XXI(81): 159-177. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Dixon, Roland B. (ed.). 1909. Achomawi Myths. Journal of American Folk-Lore XXII(85): 283-287. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Foster, John W. 2008. Ahjumawi Fish Traps. California State Parks. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Garth, T. R. 1978. Atsugewi. In Robert F. Heizer (ed.), 236-243. Handbook of North American Indians, California: Vol. 8. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

- Kniffen, Fred B. 1928. "Achomawi Geography." University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 23: 297-332.

- Kroeber, A. L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78. Washington, D.C.

- Margolin, Malcolm. 2001. The Way We Lived: California Indian Stories, Songs, and Reminiscences. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books. ISBN 093058855X.

- Mithun, Marianne. 1999. The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052129875X.

- Nevin, Bruce Edwin. 1998. Aspects of Pit River Phonology. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Olmstead, David L. 1964. A history of Palaihnihan phonology. University of California Publications in Linguistics 35. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Olmsted, David L., and Omer C. Stewart. 1978. "Achomawi." In California, Robert F. Heizer (ed.) 236-243. Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 8. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

- Pit River Tribe. [1964] 2005. Constitution of the Pit River Tribe. National Indian Law Library, Native American Rights Fund. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- Powers, Stephen. 1876. Tribes of California. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520031725.

- Stevens, Michelle, and Dale C. Darris. 2006. Common Camas. Plant Guide. Washington DC: United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Voeglin, Erminie. 1946. Culture element distributions, XX: Northeast California. University of California Anthropological Records 7(2): 47-251.

External links

All links retrieved June 14, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Achomawi history

- Achumawi_language history

- Pit_River history

- Achomawi_traditional_narratives history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.